St. Alphege (also Aelfheah) is one of the most beloved holy primates of the early English Church, whose liturgical veneration was nationwide for many centuries. He is also the only Orthodox Archbishop of Canterbury who became a martyr. Pious English people for 1000 years have remembered and honored him as a hero, archpastor, ascetic, defender of his flock and his nation. He is mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and in many other early sources, his most famous Life was written in prose and verse in the late eleventh century by the cleric and hagiographer Osbern of Canterbury, who also composed the Lives of Sts. Dunstan and Odo of Canterbury. His prose Life survives.

St. Alphege was born in about 953 to a noble family, most probably in what is now Weston, a small suburb of the city of Bath in Somerset. From his childhood he knew that his vocation was to serve God and people selflessly. He was drawn to a very austere ascetic life even as a very young man. With the permission of his widowed mother, Alphege probably in his early twenties became a monk and joined the Monastery of Deerhurst in Gloucestershire near the town of Tewkesbury. The village of Deerhurst remains a gem to this day as it boasts of two Saxon churches closely connected with that monastery, both of which are over 1000 years old. At Deerhurst Alphege gained much experience and gathered many disciples around him. But the great ascetic found the rule of Deerhurst (which was quite strict in itself) not stern enough for him and so several years later he left for Somerset where he lived for some while as a hermit in a solitary cell he built for himself. It is believed his hermitage was at or near his birthplace of Weston close to Bath. All the neighboring folk came to love him for his asceticism, compassion, care and amicable nature.

In about 982 Alphege was appointed Abbot of Bath Monastery and he remained in this post for some two years. Many of the monastery brethren were his old and new disciples. Monastic life under him was at a very high level and the saint used to say that it is better to stay and live in the world than to become a bad monk. His contemporaries noted that the generosity of Alphege towards the poor and needy and his almsgiving were boundless, and so everybody soon loved him. By that time Alphege became a disciple of St. Dunstan of Canterbury, the celebrated archpastor of his nation who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 959 to 988.

Thus, in 984, following the repose of the holy Hierarch Ethelwold of Winchester, on the recommendation of St. Dunstan (after a miraculous vision) St. Alphege was consecrated the next Bishop of Winchester. Remarkably, Alphege was the second bishop of that see with this name: one of his predecessors in that bishopric was Alphege the Elder, or Alphege “the Bald”, who is also venerated as a saint. While at Winchester, Alphege built very many churches in this then capital city and across his diocese, worked on improving the discipline and the genuine Christian life among the clergy and laity alike. He continued to live a holy ascetic life. The saint paid so much attention to care for the destitute and unfortunate that, according to some evidence, soon there were no more beggars left in the diocese! And St. Alphege promoted the liturgical and popular veneration of Sts. Swithin and Ethelwold of Winchester whom he venerated dearly. St. Alphege’s archpastoral ministry at Winchester continued for over twenty years. The holy bishop greatly encouraged learning throughout his ministry. The Diocese of Winchester at that time was one of the strongest and most influential in the whole of England.

Alphege was not only an ascetic, archpastor and almsgiver, but also an able and wise advisor of the king. At that time England was ruled by Ethelred the “Unready” (ruled 978-1016), and the country was going through very hard times of constant Danish raids and recurring attacks. Ethelred's lack of determination and his utter inability to confront the raging Danes after he succeeded his murdered half-brother St. Edward the Martyr led to his repeated payment of tributes (so-called ‘danegeld’) to the Danes to prevent their attacks. However, the latter kept returning to England with new threats. By 994 the devastations of the pagan Vikings became so ferocious that the king realized that a new approach to the pirates was needed.

The holy Bishop of Winchester knew what the right strategy should be. So it was decided to destroy the alliance between the Kings of the Danes and of Norway. The latter then was Olaf I Tryggvason (c.969-c.1000), the namesake of St. Olaf II Haraldsson (c.995–1030), who is venerated as the enlightener of Norway. Olaf I had been baptized shortly before—according to one tradition that took place in the Isles of Scilly off the coast of Cornwall. Both the king and the saint invited him to Hampshire (the county in which then the English capital of Winchester was situated) and organized a meeting with him. St. Alphege chrismated him (which is necessary after baptism), while Ethelred gave him many gifts. Olaf promised never to attack England again and kept his promise; this weakened the Danish attacks for a while. Following the repose of St. Dunstan in 988, St. Alphege also much contributed to the promotion of his (Dunstan’s) national veneration, being himself a very influential archpastor with an excellent reputation.

In the year 1006 by Divine providence St. Alphege, aged 53, was raised to the rank of Archbishop of Canterbury. The holy hierarch went to Rome to receive his pallium (a woolen vestment conferred by the Pope on an archbishop, consisting of a narrow circular band placed round the shoulders with a short lappet hanging from front and back: then it was used just a symbol, England was part of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Rome). But when he returned he learned that the situation had got worse. The nation was all but paralyzed, the Danes had settled in parts of the country bringing heathenism with them, while the king lacked courage and spirit none of his actions yielded any result.

With great difficulty Ethelred managed to bribe the pagans with a great sum of money and to prolong peace for a couple of years. During this short period of truce, St. Alphege did all he could to help his nation. At his advice the king undertook some reforms, which included reinforcing the navy, reorganizing the land forces, strengthening fortresses and beginning each holding of the Witenagemot (literally: “assembly of wise men,” a king’s national council or early form of parliament in pre-Conquest England) with prayer. The holy hierarch called his flock to repentance, to a devout Christian life, intensive prayer and fasting. And beyond a doubt, Alphege himself prayed for everybody day and night. As Archbishop of Canterbury he also labored for the development of liturgical life. But, unfortunately, the nation lacked unity at that time; it was very hard to consolidate and it did not have such a brave, wise and saintly ruler as Alfred the Great over a hundred years before.

So the Danes returned again and this time were irreconcilable. Even immense bribes would not help. The pagans finally sacked Kent and laid siege to Canterbury. St. Alphege served liturgies every day until the end and energetically tried to lift the spirit of its dwellers, giving Communion to many. At last the city of Canterbury—the spiritual capital of the English nation—fell. According to tradition, it was a treacherous archdeacon Aelfmaer who betrayed St. Alphege and the city: he set the fortified walls on fire and ran away (despite the fact that the archbishop had saved his life before). The pagans burst into the city and ransacked it. They at once captured St. Alphege and forced him to watch them burning the Cathedral and killing monks. The heathens also took many men and women of Canterbury prisoners and fixed a huge ransom for each of them. This was a real humiliation for England and its Church at that moment.

The Danes kidnapped the holy archbishop, most probably in late September 1011, and kept him for another seven months. They demanded a ransom of 3,000 pounds, which was an enormous sum for that time. St. Alphege firmly refused that any ransom be paid for him and forbade his dear flock to do it for his release. He resolved to give his own life for the sake of his people. The archbishop said to his persecutors: “The gold that I am giving you is the most precious Word of God.” And the saint began to preach the Gospel to his captors from captivity and for the following months brought some of them to Christ. He continuously prayed for his Church, his people and his country, for the cessation of the war, and also for the salvation of the souls of the invaders and their enlightenment. According to one tradition, an epidemic of the plague soon began and St. Alphege was freed for a very short time. During that time he blessed and gave out bread to people, and many were healed.

The martyrdom of St. Alphege took place on the Saturday of Bright Week, April 19 (according to the old calendar), 1012, when the archbishop was aged 59. On that day the Danes were about to cast off and send their ships with all the prisoners. Tasting their victory, the pirates set out banqueting with a large amount of wine. They ordered that St. Alphege be brought to them, and when that was done they demanded a ransom from him. The fearless archbishop, faithful to Christ till the end, replied that they could do with his body whatever they wanted, even take his life, but they had absolutely no power over his soul which belonged to God alone. Hearing this, the feasting Danes with their fury started to beat the man of God cruelly: with animal bones, with the head of an ox that they had eaten, and stones.

The leader of the Danes, who was sympathetic to Alphege after his preaching, attempted to defend him, promising his ships and riches for the saint’s release. But the Danes who by that time were drunk did not listen to him at all. Finally one of them hit Alphege’s head with an axe and the archbishop fell to the ground. His holy blood began to stream on the earth, while his pure soul was at once taken to the Heavenly Kingdom and eternal bliss. According to one tradition, St. Dunstan had appeared to St. Alphege during his captivity in a vision, encouraged him and predicted his martyrdom. The man of God was murdered in Greenwich in what is now London and a church was later erected on the site of his martyrdom.

The following morning the holy body of the archbishop was placed inside St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and numerous miracles were reported at his relics. The sainthood of Alphege was obvious to all. The Danes’ leader, stricken with what he had witnessed, gave many of his ships to the king and promised his personal loyalty to England. Some claim that later he became a Christian. Thus St. Alphege acted as a peace-maker and as a missionary, both at his lifetime and after his death. In 1023 when England was ruled by the Christian King Canute (1017-1035), who was Danish by origin, the King translated the relics of St. Alphege in a great solemn ceremony from London to Canterbury. Here they were placed in Canterbury Cathedral for veneration. Thus, King Canute returned the precious relics of Alphege to both the city and Cathedral which had been reduced to ruins by his fellow-countrymen eleven years before.

St. Alphege was eventually officially canonized as a saint by the Pope of Rome in the same eleventh century—one of the very first saints to be canonized by a Pope. After the Norman Conquest St. Alphege was greatly venerated by the Catholic Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury. The Norman Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury at first doubted the holiness of St. Alphege, but when Anselm assured him that the latter was a true saint of God he ordered his name to be included in the list of the liturgically venerated saints of the Cathedral and asked Osbern to write his Life (in fact the official veneration of some of the pre-Conquest saints of England was prohibited by the Normans following their barbarous invasion of England in 1066, bringing with them the new religion, the new, French, language, the new architecture, culture, feudalism and building huge castles etc). When St. Alphege’s shrine was opened in 1105 his relics appeared to be absolutely incorrupt.

Throughout the Middle Ages St. Alphege remained a nationally venerated saint and one of the most venerated saints of Canterbury. Notably, Thomas A Becket (c. 1118-1170) who is venerated as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church loved St. Alphege. As is generally known, as an Archbishop of Canterbury Becket openly opposed King Henry II, and one day in anger the monarch uttered the words that led to four of his knights at once coming to Canterbury and assassinating Becket inside the Cathedral. It was said that Becket pointed at the heroic deed and self-sacrifice of St. Alphege in his last sermon, and just before his death entrusted his own soul to God and the intercessions of St. Alphege. In ancient times quite a few churches in London and outside it were dedicated to St. Alphege, though of them only a handful still survive. The veneration of St. Alphege spread even to Scandinavia in the medieval period.

During the bloody Reformation initiated in England by Henry VIII, all the shrines within Canterbury Cathedral were barbarously destroyed and relics of nearly all of the numerous local saints were lost. The destiny of the relics of St. Alphege is not known for sure: they were either destroyed or hidden from the iconoclasts against “papist idols.” A stone slab to the north of the high altar of Canterbury Cathedral marks a possible site where the shrine of St. Alphege originally stood before the Dissolution. St. Alphege is commemorated in stained glass, carving and sculpture in a number of parish churches. There used to be a parish Church of St. Alphege in Canterbury with a rich history, which stood there for nearly 1000 years but was unfortunately closed in the late twentieth century forever.

Anglican parish churches are dedicated to St. Alphege in the village of Seasalter (a former Roman settlement and producer of salt—there the saint’s relics stopped for three nights on the journey from London to Canterbury in 1023), in the town of Whitstable in Kent along with a 800-year-old parish church in the town of Solihull (near Birmingham in the West Midlands), and in Greenwich, Edmonton and Southwark in London, and these churches testify to his truly heroic martyrdom. A Roman Catholic Church in the city of Bath in Somerset is also dedicated to him, and even a church in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, bears his name. Centuries ago there were famous churches of St. Alphege in Winchester and “St. Alphege’s Cripplegate” in the City of London. In 2012, Orthodox, Catholic and Anglican parishes of England celebrated the millennium since the martyrdom of St. Alphege with pilgrimages to the sites which mark his memory.

The memory of Holy Alphege, the archbishop who took care of the poor, worked miracles, lived as an anchorite, advised the king, acted as peace-maker, preached to the pagan Danes and finally gave his life for his people will never be erased in England.

* * *

Let us now talk of three of holy sites closely associated with our saint.

St. Mary’s Priory Church at Deerhurst

The name of the small village of Deerhurst means “a forest frequented by deer.” It is unique because the eighth-century St. Mary’s Saxon Church and the eleventh-century Odda’s Chapel of the Holy Trinity are located in it. Both constructions once were part of the Deerhurst monastery in the subkingdom of Hwicce. In the seventh century at one time Hwicce was ruled by Enfrith who had a daughter named Eafe. Eafe married the first Christian ruler of Sussex and was baptized; her confessor was the holy Irish missionary Dicul. Widowed, Eafe returned to her native kingdom where she was buried at Deerhurst Church together with her father and uncle who had been converted to Christ as well. It is not known when Deerhurst Monastery was founded but it is certain that it prospered by the eighth century. Its benefactors were Earl Ethelmund and his son Ethelric who were both buried there; the latter generously bestowed lands on Deerhurst, and so it became one of the largest communities in Gloucestershire.

Many ascetics were produced by Deerhurst, two of them were Sts. Alphege and Werstan who later lived as a hermit in Malvern and was martyred in c. 1058 by pagans. St. Alphege is depicted on one of the stained glass windows of this church to this day; another famous window depicts the Great martyr Catherine. Deerhurst was ravaged by the Danes in the ninth century and restored by St. Oswald of Worcester in the tenth century. In the eleventh century the half-Norman Edward the Confessor made Deerhurst a monastery dependent on the Abbey of St. Denis in Paris. In the Late medieval era the fame of Deerhurst was partly eclipsed by the neighboring monasteries at Gloucester, Winchcombe and Tewkesbury. Under Henry VIII all the monasteries were dissolved and the Deerhurst church (dating back to 800 or even earlier) has been used as a parish church since then.

This is one of the most complete early English churches of England. Among its interesting features are: a finely-preserved font which is over 1000 years old; several splendid sculptures of “the Angels of Deerhurst” on the exterior wall of the church—these are depicted with big, wide-open eyes and gorgeous wings, and were most probably created under Celtic and Greek influence; the pre-Norman tower which is 70 feet high; two carved stone figures of ninth century on the outer door of the porch; an unique double triangular-headed window of the ninth century; a rare very early carving of the Holy Virgin with Infant Jesus above the main entrance; a Saxon arch inside the church. Other buildings of the former Saxon monastery are currently used for parish and agricultural purposes.

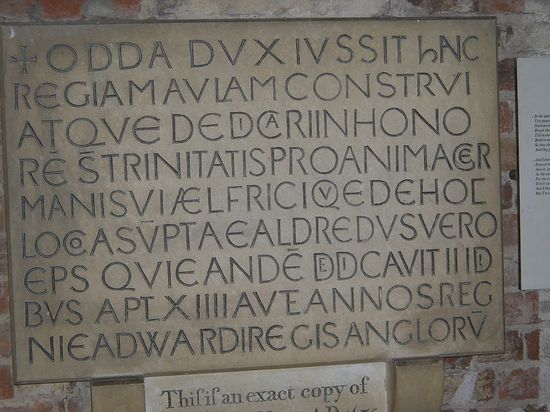

Close to the church stands Odda’s chapel with an earth floor and Saxon arches. Unlike the church, the chapel does not hold services but the faithful can enter it for quiet prayer. It was founded in 1056 by Earl Odda who is buried in Pershore. Many years later the chapel was forgotten and used for secular needs until it was miraculously rediscovered by the local priest George Butterworth (grandfather of the renowned English composer with the same name and surname who is commemorated at St. Mary’s Church on a plaque) in the nineteenth century under a thick layer of plaster and then carefully restored. Deerhurst is surely a place which is worth visiting.

Bath Abbey

The present very large and beautiful former abbey church of Sts. Peter and Paul in the center of the city of Bath is 500 years old. It is now used as an Anglican parish church and is frequently thought to be a Cathedral by visitors due to its dimensions. The first Benedictine Convent of St. Peter appeared in this former Roman town in the 670s. This was enlarged in the eighth century. It was in this monastery that St. Ethelwold of Winchester anointed St. Edgar the Peaceful the first King of all England in the year 973 (Queen Elizabeth II visited the abbey to mark this great event’s anniversary in 1973). Later St. Alphege lived as a hermit near Bath and was its illustrious abbot in the early 980s, while St. Dunstan was personally responsible for the revival of monastic life in Bath in the same century.

In 1090, Bishop John of Wells moved his see to Bath and started building a great Romanesque cathedral and monastery here. From that time on Bath was known as a prominent spiritual and monastic center. Some stones from that building still survive. The most outstanding scholar of Bath was Adelard (1080-1152) who was one of the first to introduce the Arabic (originally Hindu) numeral system to Europe. From 1245, the diocese was shared between the cities of Wells and Bath, and so it was a joint see. In 1499 Bishop Oliver King after a miraculous vision (in which he saw a ladder and angels ascending and descending and a voice told him to build a new abbey there) initiated a large-scale project of building the new (present) abbey church in Bath. It was the last large building in England in the Perpendicular style of Gothic. Oliver King never saw his building project completed as he died in 1503.

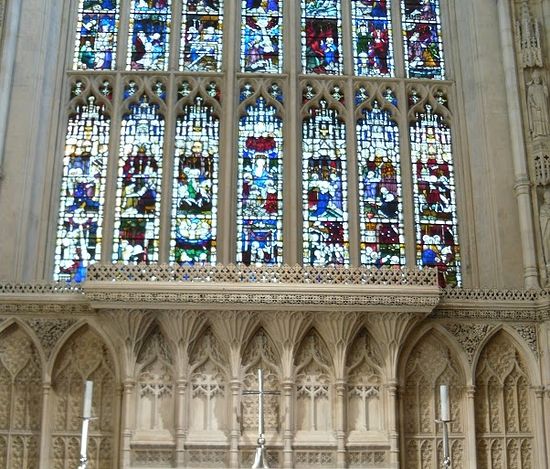

Sadly, soon after its completion the Reformation began and all the monasteries in the country were closed. So the current church was a monastic church for a very short time. It was much due to Queen Elizabeth I that the church was saved. This church does have many treasures to admire, despite the serious restoration work by George Gilbert Scott in the nineteenth century. Its fan vaulting (a distinctive feature of perpendicular style ceilings) of the local Bath stone is fantastic. The south transept has a beautiful “Jesse Tree” window showing the ancestral line of our Lord from Jesse, the father of King David. The abbey boasts of a large number of monuments and plaques dating to various periods (617 wall memorials and 847 floor stones, according to the abbey’s website) and commemorating not only Church figures and heroes, but also local wealthy families, war victims, scientists, inventors.

Among those buried in the abbey are Richard Nash (1674-1761), a local “master of ceremonies” who helped establish the fame of Bath as a spa resort; and the Oxfordshire botanist John Sibthorp (1758-1796). The distinguished portraitist William Hoare (1707-1792) lived most of his life in Bath and is commemorated in the abbey. There is a huge famous stained glass window above the high altar depicting 56 scenes of Christ’s life. Late in the twentieth century a new Chapel in honor of St. Alphege was consecrated near the altar to mark the abbey’s greatest abbot. The chapel has a very warm atmosphere. It has an Orthodox icon of St. Alphege along with a stained glass depicting the anointing of St. Edgar as a king by St. Ethelwold. The west façade contains sculptures of angels from King’s vision, as well as those of the apostles. There is an abbey heritage museum in the church vaults. The abbey is c. 70 meters (c. 225 feet) long and c. 25 meters (c. 80 feet) wide, it seats over 1000 worshippers, and is also famous for its musical traditions. The abbey is known as “the Lantern of the West” due to the light shining from its many windows at night.

St. Alphege’s Church, Greenwich

This historic church stands in the center of Greenwich—a London borough on the bank of the River Thames in the capital’s southeast. The Prime Meridian runs through Greenwich (the Saxon name means “green village”), and Greenwich Mean Time is the world’s time standard. Greenwich was known as “the sea gate of London”. Greenwich has great spiritual significance: it was here that St. Alphege was martyred.

The first church on the site of Alphege’s martyrdom appeared soon after his death. This was rebuilt in the thirteenth century: it was one of the most beautiful and important churches in England and Western Europe. In 1710 the church was damaged during a severe storm, and in the following year a commission for building 50 new churches in and near London was set up by the Parliament, the first being St. Alphege’s. It was rebuilt in 1712-14 according to the design of Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), a pupil of Christopher Wren. For some time it had the largest unsupported ceiling in Europe. Members of the Royal Family regularly attended this church.

In 1941 the church was heavily damaged during Nazi bombing but was completely restored by 1953. There is a stone slab in front of the sanctuary marking the symbolic grave of Alphege. It has an inscription made by Archbishop Anselm which reads, “He who dies for justice dies for God.” A stained glass image of Alphege can be seen in the church. In 1491 the future King Henry VIII was baptized in this temple. Many famous people are buried within St. Alphege’s, for example: the great composer of church music Thomas Tallis (1505-1585), General James Wolfe (1727-1759), architects, writers, and actors.

Holy Hieromartyr Alphege of Canterbury, pray to God for us!