From the periodical produced by the Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville (ROCOR), Orthodox Life, we present the Life of St. Peter of Krutitsa—an article that also serves to describe what was happening in the Russian Church administration after the repose of Patriarch Tikhon.

"I cannot refuse. If I refuse, then I will be a traitor of the Church..."

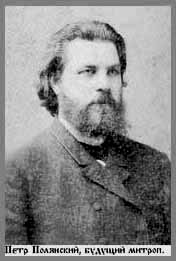

Metropolitan Peter, in the world Peter Fyodorovich Polyansky, was born on June 28, 1862 (according to another source, 1863) in the village of Storozhevoy, Korotyansky uyezd, Voronezh province. Like the holy Patriarch Tikhon, he grew up in the family of a village priest. He studied in Voronezh theological seminary, graduating in 1885, and then in the Moscow Theological Academy. On graduating in 1892 as a candidate of theology, Peter Polyansky remained in the Academy as the second assistant of the inspector. Meanwhile he worked on a dissertation devoted to the first epistle of the holy Apostle Paul to Timothy. This major work, for which the author was awarded the degree of master of theology on March 4, 1897, is still considered one of the best works on the hermeneutics of the New Testament.

Peter Fyodorovich Polyansky.

Peter Fyodorovich Polyansky.

In 1917-18, Peter Fyodorovich was a delegate to the Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, where Patriarch Tikhon made him one of his closest co-workers. In 1920 he was tonsured into monasticism by Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky), and on September 25 (April 25, according to another source) he was consecrated Bishop of Podolsk, a vicariate of the Moscow diocese, by Patriarch Tikhon. When Patriarch Tikhon asked him to accept monasticism, the priesthood and the episcopacy, and become his assistant in administering the Russian Church, Peter came home and said:

"I cannot refuse. If I refuse, then I will be a traitor of the Church. But when I agree, I know that I will thereby be signing my death warrant."

In 1923 the foreign journal Tserkovnye Vedomosti wrote: "Bishop Peter of Podolsk has been arrested several times, the last time on August 21, 1921."

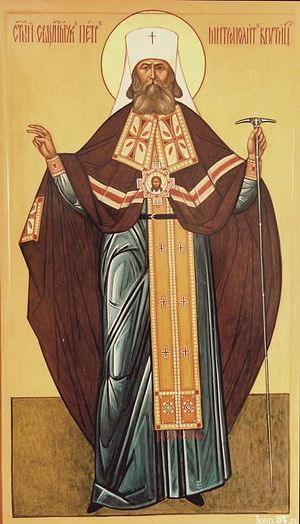

In the second half of 1923 he was released, whereupon Patriarch Tikhon raised him to the rank of archbishop. And after the arrest of Bishop Hilarion (Troitsky) the Patriarch made him his closest assistant, raising him to the rank of metropolitan of Krutitsa in the spring of 1924. Many years later Protopriest Basil Vinogradov recalled of that time: "No member of the Patriarch's administration, on going to work in the morning, could be sure that he would not be arrested for participating in an illegal organization, or that he would not find the Patriarch's residence sealed."

On March 25 / April 7, 1925, his Holiness Patriarch Tikhon reposed in the Lord. On March 30 / April 12, the deceased Patriarch's will of December 25 / January 7, 1924/25 was discovered and read out. It said that in the event of the Patriarch's death and the absence of the first two candidates for the post of patriarchal locum tenens, "our patriarchal rights and duties, until the lawful election of a new patriarch,... pass to his Eminence Peter, metropolitan of Krutitsa." At the moment of the Patriarch's death (as the rumour went, by poisoning), the first two hierarchs indicated by him as candidates of the post of locum tenens, Metropolitans Cyril of Kazan and Agathangel of Yaroslavl, were in exile. Therefore the 59 assembled hierarchs decided that "Metropolitan Peter cannot decline from the obedience given him and.. must enter upon the duties of the patriarchal locum tenens."

Almost immediately the renovationist schismatics, encouraged by the Patriarch's death, energetically tried to obtain union with the Orthodox Church in time for their second Council, which was due to take place in the autumn of 1925. Their attempts were aided by the Soviet authorities, who put all kinds of pressures on the hierarchs to enter into union with the renovationists. A firm lead was required from the head of the Church, and in his proclamation dated July 28, 1925 this is exactly what Metropolitan Peter provided.

"You're all liars. You give nothing, except promises."

Evgeny Tuchkov, head of the fourth OGPU, in charge of dividing the Church.

Evgeny Tuchkov, head of the fourth OGPU, in charge of dividing the Church. "The so-called new-churchmen should talk of no reunion with the Orthodox Church until they show a sincere repentance for their errors. The chief of these is that they arbitrarily renounced the lawful hierarchy and its head, the most holy Patriarch, and attempted to reform the Church of Christ by self-invented teaching (The Living Church, nos. 1-11); they transgressed the ecclesiastical rules which were established by the Ecumenical Councils (the pronouncements of the pseudo-Council of May 4, 1923); they rejected the government of the Patriarch, which was established by the Council and acknowledged by all the Eastern Orthodox Patriarchs, i.e., they rejected what all Orthodoxy accepted, and besides, they even condemned him at their pseudo-Council. Contrary to the rules of the holy Apostles, the Ecumenical Councils and the holy Fathers (Apostolic canons 17,18; Sixth Ecumenical Council, canons 3, 13, 48; St. Basil the Great, canon 12), they permit bishops to marry and clerics to contract a second marriage, i.e., they transgress what the entire Ecumenical Church acknowledges to be a law, which can be changed only by an Ecumenical Council.

"The reunion of the so-called new-churchmen with the holy Orthodox Church is possible only on the condition that each of them recants his errors and submits to a public repentance for his apostasy from the Church. We pray the Lord God without ceasing that He may restore the erring into the bosom of the holy Orthodox Church."

This epistle had a sobering and strengthening effect on many wavering clerics. As the renovationist Vestnik Svyashchennago Synoda was forced to admit: "Immediately after Peter's appeal came out, the courage of the 'leftist' Tikhonites disappeared." So at their Council in the Church of Christ the Saviour in Moscow the schismatics planned their revenge. "Metropolitan-Evangelist" Vvedensky publicly accused Metropolitan Peter of involvement with an emigre monarchist plot. In support of this claim he produced a patently forged denunciation by the renovationist bishop of Latin America Nicholas, a very dubious person who had several times crossed into schism and back into the Church.

The Bolsheviks gave ready support to the renovationists in their battle against Peter. Thus Savelyev writes: "On November 11, 1925, Yaroslavsky, Skvortsov-Stepanov and Menzhinsky were discussing Tuchkov's report 'On the future policy in connection with the death of Tikhon'. A general order was given to the OGPU to accelerate the implementation of the schism that had been planned amidst the supporters of Tikhon. Concrete measures were indicated with great frankness: 'In order to support the group in opposition to Peter (the patriarchal locum tenens...) it is resolved to publish in Izvestia a series of articles compromising Peter, and to use towards this end materials from the recently ended renovationist council.'.. The censorship and editing of the articles was entrusted to the party philosopher Skvortsov-Stepanov. He was helped by Krasikov (Narkomyust) and Tuchkov (OGPU). This trio was given the task of censuring the declaration against Peter which was being prepared by the anti-Tikhonite group. Simultaneously with the publication in Izvestia of provocative articles against the patriarchal locum tenens, the Anti-Religious commission ordered the OGPU 'to initiate an investigation against Peter'."

Meanwhile, Tuchkov initiated discussions with Peter with regard to "legalizing" the Church.

This "legalization" promised to relieve the Church's rightless position, but on the following conditions: 1) the issuing of a declaration of a pre-determined content; 2) the exclusion from the ranks of the bishops of those who were displeasing to the authorities; 3) the condemnation of the emigre bishops; and 4) the participation of the government, in the person of Tuchkov, in the future activities of the Church. However, Metropolitan Peter refused to accept these conditions and also refused to sign the text of the declaration Tuchkov offered him. And he continued to be a rock in the path of the atheists' plans to seize control of the Church. For, as he once said to Tuchkov:

"You're all liars. You give nothing, except promises. And now please leave the room, we are about to have a meeting."

Metropolitan Peter must have foreseen his fate. For on November 22 / December 5, 1925 he composed a will in the event of his death. And on the next day he wrote another in the event of his arrest. On December 9 (new style), the Anti-Religious Commission (more precisely: "the Central Committee Commission for carrying out the decree on the separation of Church and State") met and approved of the activities of the OGPU in inciting the Church groupings against each other. They also determined the timing of Metropolitan Peter's arrest. And the next day, December 10, Metropolitan Peter was placed under house-arrest...

On December 12, Metropolitan Peter was taken to the inner prison at the Lubyanka. At the same time a group of bishops living in Moscow whom the GPU considered to be of like mind with him were also arrested: Archbishops Nicholas of Vladimir, Pachomius of Chernigov, Procopius of the Chersonese and Gurias of Irkutsk, and Bishops Parthenius of Ananievsk, Damascene of Glukhov, Tikhon of Gomel, Barsonuphius of Kargopol and others.

The events that followed Peter's arrest and imprisonment are not at all clear. We know that a struggle for power took place between Archbishop Gregory (Yatskovsky) of Ekaterinburg (Sverdlovsk) and a group of bishops, on the one hand, and Metropolitan Sergius of Nizhni-Novgorod (Gorky), on the other, which Sergius eventually won. The most widely accepted version of events goes something like this.

Anarchy in the Church

On December 1/14, although unable to leave Nizhni-Novgorod at the time, Metropolitan Sergius announced that he was taking over the Church's administration in accordance with Metropolitan Peter's instruction. However, Metropolitan Sergius was prevented by the OGPU from coming to Moscow, and on December 9/22, 1925, a group of nine bishops led by Archbishop Gregory of Ekaterinburg gathered at the Donskoy monastery. The Gregorians, as they came to be called, then declared that since Metropolitan Peter's activity was counter-revolutionary, and since with his arrest the Church was deprived of direction, they were organizing a Higher Temporary Church Council. This organization was legalized by the authorities on December 20 / January 2.

On January 1/14, Metropolitan Sergius wrote to Archbishop Gregory demanding an explanation for his usurpation of power. Gregory replied on January 9/22, saying that while they recognized the rights of the three locum tenentes, "we know no conciliar decision concerning you, and we do not consider the transfer of administration and power by personal letter to correspond to the spirit and letter of the holy canons."

Sergius wrote again on January 16/29, impeaching Gregory and his fellow bishops, banning them from serving and declaring all their ordinations, appointments, awards, etc., since December 9/22 to be invalid. On the same day, three Gregorian bishops wrote to Metropolitan Peter claiming that they had not known, in their December meeting, that he had transferred his rights to Sergius, and asking him to bless their administration. The free access the Gregorians had to Peter during this period, and the fact that Sergius was at first prevented from coming to Moscow, suggests that the OGPU, while not opposing Sergius, at first favoured the Gregorians as their best hope for dividing the Church.

Fearing anarchy in the Church, Metropolitan Peter went part of the way to blessing the Gregorians' undertaking. However, instead of the Gregorian Synod, he created a temporary "college" to administer the Church consisting of Archbishop Gregory, Archbishop Nicholas (Dobronravov) of Vladimir and Archbishop Demetrius (Belikov) of Tomsk, who were well-known for their firmness. This resolution was made during a meeting with the Gregorians in the GPU offices on January 19 / February 1. Tuchkov, who was present at the meeting, was silent about the fact that Nicholas was in prison. He agreed to summon Demetrius from Tomsk, and even showed Peter the telegram. But he never sent it. When Peter, feeling something was wrong, asked for the inclusion of Metropolitan Arsenius (Stadnitsky) in the college of bishops, Tuchkov again agreed and promised to sign Peter's telegram to him. Again, the telegram was not sent.

Now it has been argued by Regelson that Metropolitan Peter's action in appointing deputies was not canonical (as the Gregorians also implied), and created misunderstandings that were to be ruthlessly exploited later by Metropolitan Sergius. A chief hierarch does not have the right to transfer the fullness of his power to another hierarch as if it were a personal inheritance: only a Council representing the whole Local Church can elect a leader to replace him. Patriarch Tikhon's appointment of three locum tenentes was an exceptional measure, but one which was nevertheless entrusted to him by—and therefore could claim the authority of—the Council of 1917-18. However, the Council made no provision for what might happen in the event of the death or removal of these three. In such an event, therefore, patriarchal authority ceased, temporarily, in the Church; and there was no canonical alternative, until the convocation of another Council, but for each bishop to govern his diocese independently while maintaining links with neighbouring dioceses, in accordance with the Patriarch's ukaz no. 362 of November 7/20, 1920.

In defence of Metropolitan Peter it may be said that it is unlikely that he intended to transfer the fullness of his power to Metropolitan Sergius, but only the day-to-day running of the administrative machine. Thus in his declaration of December 6, 1925, he gave instructions on what should be done in the event of his arrest, saying that even a hierarchical "college" expressing his authority as patriarchal locum tenens would not be able to decide "the principal questions affecting the whole Church, whose realization in life could be permitted only with our blessing". He must have been thinking of Patriarch Tikhon's similar restrictions on the renovationists who tried to take over the administration in May, 1922.

Moreover, he continued to insist on the commemoration of his name as patriarchal locum tenens in the Divine services. This was something that Patriarch Tikhon had not insisted upon when he transferred the fullness of his power to Metropolitan Agathangelus. The critical distinction here is that whereas the patriarchal locum tenens has, de jure, all the power of a canonically elected Patriarch and need relinquish his power only to a canonically convoked Council of the whole local Church, the deputy of the locum tenens has no such fullness of power and must relinquish such rights as he has at any time that the Council or the locum tenens requires it.

Why, then, did Metropolitan Peter not invoke ukaz no. 362 and bless the decentralization of the Church's administration at the time of his arrest? Probably for two important reasons. (1) The restoration of the patriarchate was one of the main achievements of the Moscow Council of 1917-18, and had proved enormously popular. Its dissolution might well have dealt a major psychological blow to the masses, who were not always educated enough to understand that the Church could continue to exist either in a centralized (though not papist) form, as it had in the East from 312 to 1917, or in a decentralized form, as in the catacombal period before Constantine the Great and during the iconoclast persecution of the eighth and ninth centuries. (2) The renovationists—who still constituted the major threat to the Church in Metropolitan Peter's eyes—did not have a patriarch, and their organization was, as we have seen, closer to the synodical, state-dependent structure of the pre-revolutionary Church. The presence or absence of a patriarch or his substitute was therefore a major sign of the difference between the true Church and the false for the uneducated believer.

Let us now return to the sequence of events. On January 22 / February 4, 1926, Metropolitan Peter fell ill and was admitted to the prison hospital. A war for control of the Church now developed between the Gregorians and Sergius. The Gregorians pointed to Sergius' links with Rasputin and the "Living Church": "On recognizing the Living Church, Metropolitan Sergius took part in the sessions of the HCA, recognized the lawfulness of married bishops and twice-married priests, and blessed this lawlessness. Besides, Metropolitan Sergius sympathized with the living church council of 1923, did not object to its decisions, and therefore confessed our All-Russian Archpastor and father, his Holiness Patriarch Tikhon, to be 'an apostate from the true ordinances of Christ and a betrayer of the Church', depriving him of his patriarchal rank and monastic calling. True, Metropolitan Sergius later repented of these terrible crimes and was forgiven by the Church, but that does not mean that he should stand at the head of the Church's administration."

However, these arguments, well-based though they were, were not strong enough to maintain the Gregorians' position, which deteriorated as several bishops declared their support for Sergius.

Yaroslavsky, Tuchkov and the OGPU had already succeeded in creating a schism between Metropolitan Sergius and the Gregorians. They now tried to fan the flames of schism still higher by releasing Metropolitan Agathangelus, the second candidate for the post of patriarchal locum tenens, from exile and persuading him to declare his assumption of the post of locum tenens, which he did officially from Perm on April 5/18. They also decided, at a meeting in the Kremlin on April 11/24, to "strengthen the third Tikhonite hierarchy—the Temporary Higher Ecclesiastical Council headed by Archbishop Gregory, as an independent unit."

On April 9/22, Metropolitan Sergius wrote to Metropolitan Peter at the Moscow GPU, as a result of which Peter withdrew his support from the Gregorians, signing his letter to Metropolitan Sergius: "the penitent Peter". It would be interesting to know whether Sergius knew of Metropolitan Agathangelus' declaration four days earlier when he wrote to Peter. Hieromonk Damascene (Orlovsky) claims that Agathangelus did not tell Sergius until several days later—but the evidence is ambiguous. If Sergius already knew of Agathangelus' assumption of the rights of locum tenens, then his keeping quiet about this very important fact in his letter to Metropolitan Peter was dishonest and misleading. For he must have realized that Metropolitan Agathangelus, having returned from exile (he arrived in his see of Yaroslavl on April 14/27), had every right to assume power as the eldest hierarch and the only patriarchal locum tenens named by Patriarch Tikhon who was in freedom at that time. In fact, with the appearance of Metropolitan Agathangelus the claims of both the Gregorians and Sergius to first-hierarchical power in the Church collapsed. But Sergius, having tasted of power, was not about to relinquish it so quickly. And just as Metropolitan Agathangelus' rights as locum tenens were swept aside by the renovationists in 1922, so now the same hierarch was swept aside again by the former renovationist Sergius.

The chronology of events reveals how the leadership of the Russian Church was usurped for the second time. On April 17/30, Sergius wrote to Agathangelus rejecting his claim to the rights of the patriarchal locum tenens on the grounds that Peter had not resigned his post. In this letter Sergius claims that he and Peter had exchanged opinions on Agathangelus' letter in Moscow on April 9/22—but neither Sergius nor Peter mention Agathangelus in the letters they exchanged on that day and which are published by Gobunin. Therefore it seems probable that Peter's decision not to resign his post was based on ignorance of Agathangelus' appearance on the scene.

On April 30 / May 13, Agathangelus met Sergius in Moscow (Nizhni-Novgorod, according to another source), where, according to Sergius, they agreed that if Peter's trial [for unlawfully handing over his authority to the Gregorians] ended in his condemnation, Sergius would hand over his authority to Agathangelus. However, Sergius was simply playing for time, in order to win as many bishops as possible to his side. And on May 3/16, he again wrote to Agathangelus, in effect reneging on his agreement of three days before: "If the affair ends with Metropolitan Peter being acquitted or freed, I will hand over to him my authority, while your eminence will then have to conduct discussions with Metropolitan Peter himself. But if the affair ends with his condemnation, you will be given the opportunity to take upon yourself the initiative of raising the question of bringing Metropolitan Peter to a church trial. When Metropolitan Peter will be given over to a trial, you can present your rights, as the eldest [hierarch] to the post of Deputy of Metropolitan Peter, and when the court will declare the latter deprived of his post, you will be the second candidate to the locum tenancy of the patriarchal throne after Metropolitan Cyril." In other words, Sergius in a cunning and complicated way rejected Agathangelus' claim to be the lawful head of the Russian Church, although this claim was now stronger than Metropolitan Peter's (because he was in prison and unable to rule the Church) and much stronger than Sergius'.

On May 7/20, Agathangelus sent a telegram to Sergius: "You promised to send a project to the Bishops concerning the transfer to me of the authorizations of ecclesiastical power. Be so kind as to hurry up." On the same day Sergius replied: "Having checked your information, I am convinced that you have no rights; [I will send you] the details by letter. I ardently beseech you: do not take the decisive step." On May 8/21, Agathangelus sent another telegram threatening to publish the agreement he had made with Sergius and which he, Sergius, had broken. On May 9/22, Sergius wrote to Peter warning him not to recognize Agathangelus' claims (the letter, according to Hieromonk Damascene, was delivered personally by Tuchkov). However, Peter ignored Sergius' warning and wrote to Agathangelus, congratulating him on his assumption of the rights of patriarchal locum tenens and assuring him of his loyalty. At this point Sergius' last real canonical grounds for holding on to power—the support of Metropolitan Peter—collapsed.

But Agathangelus only received this letter on May 31. The (OGPU-engineered?) delay proved to be decisive. For on May 24, after Sergius had again written rejecting Agathangelus' claims, the latter, according to Regelson, wrote: "Continue to rule the Church. For the sake of the peace of the Church I propose to resign the office of locum tenens."

On the same day Sergius, savagely pressing home his advantage, wrote to the administration of the Moscow diocese concerning the handing over of Agathangelus to a trial by the hierarchs then resident in Moscow.On June 9 Metropolitan Peter wrote to Metropolitan Agathangelus that if Agathangelus refused to take up the position, or was unable to do so, the rights and duties of the locum tenancy would revert to him, Metropolitan Peter, and the deputyship to Sergius. However, on June 12 Metropolitan Agathangelus wrote to Peter renouncing his assumption of the post of locum tenens. The way was now open for Sergius to resume power. And in the same month Metropolitan Peter was transferred to the political isolation cell in the Spaso-Efimiev monastery in Suzdal, where he remained until the autumn.

"I will remain faithful to the Orthodox Church to death itself."

In December, 1926, Metropolitan Peter was transferred from Suzdal to a GPU prison in Moscow, where Tuchkov proposed that that he renounce his locum tenancy. Peter refused, and then sent a message to everyone through a fellow prisoner that he would "never under any circumstances leave his post and would remain faithful to the Orthodox Church to death itself". But on December 19 / January 1, 1926/27, while in Perm prison on his way to exile in Tobolsk, Metropolitan Peter confirmed Sergius as his deputy. Apparently he was unaware of the recent changes in the leadership of the Church. In any case, he was to have no further direct effect on the administration of the Church, being subjected, in the words of Fr. Vladimir Rusak, to "12 years of unbelievable torments, imprisonment, tortures and exile beyond the Arctic Circle."

Fr. Vladimir tells the following story about Metropolitan Peter when he was on his way to exile in Siberia. One dark night "he was thrown out of the railway carriage while it was still moving (apparently more than one bishop perished in this way). It was winter, and the metropolitan fell into a snow-drift as if into a feather-bed, so that he did not hurt himself. With difficulty he got out of it and looked round. There was a wood, and snow, and no signs of life. For a long time he walked over the virgin snow, and at length, exhausted, he sat down on a stump. Through his torn rasson the frost chilled him to the bone. Sensing that he was beginning to freeze to death, the metropolitan started to read the prayers for the dying.

"Suddenly he saw a huge bear approaching him.

"The thought flashed through his mind: 'He'll tear me to pieces'. But he did not have the strength to run away. And where could he run?

"But the bear came up to him, sniffed him and peacefully lay down at his feet. Warmth wafted out of his huge bear's hide. Then he turned over with his belly towards the metropolitan, stretched out his whole length and began to snore sweetly. Vladyka wavered for a long time as he looked at the sleeping bear, then he could stand the cold no longer and lay down next to him, pressing himself to his warm belly. He lay down and turned first one and then the other side towards the beast in order to get warm. Meanwhile the bear breathed deeply in his sleep, enveloping him in his warm breath.

"When the dawn began to break, the metropolitan heard the distant crowing of cocks: a dwelling-place. He got to his feet, taking care not to wake up the bear. But the bear also got up, and after shaking himself down plodded off towards the wood.

"Rested now, Vladyka went towards the sound of the cocks and soon reached a small village. After knocking at the end house, he explained who he was and asked for shelter, promising that his sister would pay the owners for all trouble and expenses entailed. They let Vladyka in and for half a year he lived in this village. He wrote to his sister, and she arrived. But soon after her other 'people' in uniform also came..."

In March, 1927, Metropolitan Sergius was released from prison. He immediately formed a "Synod" of twelve of the most disreputable bishops in Russia. And then, in July, he issued his famous declaration in which he placed the Church in more or less complete submission to the atheists.

From February to April, 1927, Metropolitan Peter was in exile in the Abalakhsky monastery in Tobolsk. When his cell-attendant came to him, Metropolitan Peter asked him:

"Was it with the knowledge of the authorities that you came here?"

On receiving a negative reply, he told him to go and inform the authorities of his arrival. For this, both Metropolitan Peter and his cell-attendant were thrown into prison in Tobolsk, where they remained until June.

While there, he heard that they wanted to issue a decree stopping the commemoration of his name in the churches. "It is not wounded self-love," he said, "nor resentment which forces me to be anxious about this, but I fear that if my name ceases to be commemorated it will be difficult to distinguish between the Tikhonite and renovationist churches." He added that the investigator Tuchkov was in charge of church affairs, which was impermissible, and he said that he would remain alone like St. Athanasius of Alexandria.

On July 9, Metropolitan Peter was exiled along the river Ob to the Arctic settlement of Khe, which was in the tundra two hundred versts from Obdorsk. There, seriously ill and deprived of the possibility of communicating with the world, he was doomed to a slow death. On August 29 / September 11, he suffered his first attack of angina and from that time never left his bed. He was taken to Obdorsk, where he was advised to petition for a transfer to another place with a better climate. But his petition was refused, and he remained in Khe until September, 1928, when he was transferred to Tobolsk prison. There Tuchkov offered him his freedom if he would renounce his locum tenancy. Metropolitan Peter refused and on May 11, 1928 he was returned to Khe, with the period of his exile extended by three years.

According to Metropolitan Manuel (Lemeshevsky), during his exile Metropolitan Peter composed a moleben for the suffering world and a short blessing of the water with a special prayer.

"My duty and conscience do not allow me to remain indifferent to such a sorrowful phenomenon."

According to Protopresbyter Michael Polsky, Metropolitan Peter wrote to Sergius, saying that if he did not have the strength to defend the Church he should hand over his duties to someone stronger. Similar information was provided by the Priests Elijah Pirozhenko and Peter Novosiltsev after they had visited Metropolitan Peter. In May, 1929, Bishop Damascene of Glukhov sent a messenger to Metropolitan Peter, and from his reply was able to write: "Granddad (i.e. Metropolitan Peter) spoke about the situation and the further consequences to be deduced from it almost in my own words".

On September 17, 1929, the priest Gregory Seletsky wrote to Metropolitan Joseph of Petrograd on behalf of Archbishop Demetrius (Lyubimov): "I am fulfilling the request of his Eminence Archbishop Demetrius and set out before you in written form that information which the exiled Bishop Damascene has communicated to me. He succeeded in making contact with Metropolitan Peter, and in sending him, via a trusted person, full information about everything that has been taking place in the Russian Church. Through this emissary Metropolitan Peter orally conveyed the following:

"1. You Bishops must yourselves remove Metropolitan Sergius.

"2. I do not bless you to commemorate Metropolitan Sergius during Divine services.

"3. The Kievan act of the so-called "small council of Ukrainian bishops" concerning the retirement of 16 bishops from the sees they occupy is to be considered invalid.

"4. The letter of Bishop Basil (the vicar of the Ryazan diocese) gives false information. [This refers to a forgery concocted by the sergianists which purported to show that Metropolitan Peter recognized Metropolitan Sergius.]

"5. I will reply to questions in writing."

Metropolitan Sergius (Starogorodsky).

Metropolitan Sergius (Starogorodsky). On February 13/26, 1930, after receiving news from a certain Deacon K. about the true state of affairs in the Church, Metropolitan Peter wrote to Metropolitan Sergius, saying: "Of all the distressing news I have had to receive, the most distressing was the news that many believers remain outside the walls of the churches in which your name is commemorated. I am filled with spiritual pain both about the disputes that have arisen with regard to your administration and about other sad phenomena. Perhaps this information is biassed, perhaps I am not sufficiently acquainted with the character and aims of the people writing to me. But the news of disturbances in the Church come to me from various quarters and mainly from clerics and laymen who have made a great impression on me. In my opinion, in view of the exceptional circumstances of Church life, when normal rules of administration have been subject to all kinds of distortion, it is necessary to put Church life on that path on which it stood during your first period as deputy. So be so good as to return to that course of action whcih was respected by everybody. I repeat that I am very sad that you have not written to me and have confided your plans to me. Since letters come from other people, yours would undoubtedly have reached me..."

After this letter was published, the authorities again tried to force Metropolitan Peter to renounce the locum tenancy and to become an agent of the OGPU. But he refused. On August 17, 1930, he was arrested and imprisoned in the Tobolsk and Ekaterinburg prisons in solitary confinement with no right to receive parcels or visitors. On March 11, 1931, after describing the sufferings of his life in Khe (which included the enmity of three renovationist priests), he posed the following question in a letter to J.B. Polyansky: "Will not a change in locum tenens bring with it a change also in his deputy? Of course, it is possible that my successor, if he were to find himself incapable of carrying out his responsibilities directly, would leave the same person as his deputy—that is his right. But it is certain, in my opinion, that the carrying out of his duties by this deputy would have to come to an end at the same time as the departure of the person for whom he is deputizing, just as, according to the declaration of Metropolitan Sergius, with his departure the synod created by him would cease to exist. All this and other questions require thorough and authoritative discussion and canonical underpinning... Be so kind as to bow to Metropolitan Sergius on my behalf, since I am unable to do this myself, and send him my fervent plea that he, together with Metropolitan Seraphim and Archbishop Philip, to whom I also bow, work together for my liberation. I beseech them to defend, an old man who can hardly walk. I was always filled with a feeling of deep veneration and gratitude to Metropolitan Sergius, and the thought of some kind of worsening of our relations would give me indescribable sorrow."

On March 27, Metropolitan Peter wrote to B.P. Menzhinsky: "I was given a five-year exile which I served in the far north in the midst of the cruellest frosts, constant storms, extreme poverty and destitution in everything. (I was constantly on the edge of the grave.) But years passed, and there remained four months to the end of my exile when the same thing began all over again—I was again arrested and imprisoned by the Urals OGPU. After some time I was visited by comrade J.V. Polyansky, who suggested that I renounce the locum tenancy. But I could not accept such a suggestion for the following reasons which have a decisive significance for me. First of all I would be transgressing the established order according to which the locum tenens must remain at his post until the convening of a council. A council convened without the sanction of the locum tenens would be considered uncanonical and its decisions invalid. But in the case of my death the prerogatives of the locum tenens will pass to another person who will complete that which was not done by his predecessor. Moreover, my removal would bring in its wake the departure also of my deputy, Metropolitan Sergius, just as, according to his declaration, with his departure from the position of deputy the Synod created by him would cease to exist. I cannot be indifferent to such a circumstance. Our simultaneous departure does not guarantee church life from various possible frictions, and, of course, the guilt would be mine. Therefore in the given case it is necessary that we discuss this matter together, just as we discussed together the questions relating to my letter to Metropolitan Sergius dated December, 1929. Finally, my decree, coming from prison, would undoubtedly be interpreted as made under pressure, with various undesirable consequences."

"Such an occupation is incompatible with my calling..."

In the spring of 1931 Tuchkov suggested to Metropolitan Peter that he work as an informer for the GPU. On May 25, Metropolitan Peter wrote to Menzhinsky that "such an occupation is incompatible with my calling and is, besides, unsuited to my nature." And again he wrote to Menzhinsky: "In our weakness we fall more or less short of that ideal, that truth, which is enjoined upon Christians. But it is important not to be burdened only by earthly matters and therefore to refrain from violently murdering the truth and departing from its path. Otherwise it would be better to renounce God altogether... In this matter one would come up against two completely contradictory principles: Christian and revolutionary. The basis of the former principle is love for one's neighbour, forgiveness of all, brotherhood, humility; while the basis of the latter principle is: the end justifies the means, class warfare, pillage, etc. If you look at things from the point of view of this second principle, you enter upon the revolutionary path and hurl yourself into warfare, and thereby you renounce not only the true symbol of the Christian Faith and annihilate its foundations—the idea of love and the rest, but also the principles of the confession of the faith. There is no need to say how this dilemma—between love for one's neighbour and class warfare—is to be resolved by a seriously believing person who is, moreover, not a hireling, but a real pastor of the Church. He would hardly know any peace for the rest of his life if he subjected himself to temptation from the direction of the above-mentioned contradictions."

Metropolitan Peter's sufferings after the visits of Tuchkov were so acute that for some days his right arm and leg were paralyzed.

On July 23, 1931, the OGPU condemned Metropolitan Peter to five years in a concentration camp "for stubborn struggle against Soviet power and persistent counter-revolutionary activity". Immediately after this sentence had been passed, OGPU agents Agranov and Tuchkov sent the administration of the Ekaterinburg prison a note recommending that Metropolitan Peter be kept under guard in the inner isolation-cell.

In the summer of 1933 they substituted his walks in the common courtyard with walks in a tiny, separate courtyard which was like a damp cellar whose floor was constantly covered with pools of rain-water and whose air was filled with smells from a latrine which was just next to the courtyard. When Vladyka saw this place he had an asthma attack and barely made it to his room. Soon the prison administration told him that the money which had been given for him had been spent and that they would no longer be providing him with additional food from the refectory. Vladyka was strictly isolated. The doctor's assistant who was in the room next to him was strictly forbidden to enter into any kind of relations with him, and his request to meet the local bishop was refused.

"Not an act of my will alone."

In August, 1933, Vladyka wrote to the authorities: "In essence, the locum tenancy is of no interest to me personally. On the contrary, it constantly keeps me in the fetters of persecution.. But I am bound to reckon with the fact that the solution of the given question does not depend on my initiative and cannot be an act of my will alone. By my calling I am inextricably bound to the spiritual interests and will of the whole Local Church. So the question of the disposal of the locum tenancy, not being a personal question, cannot be left to my discretion, otherwise I would turn out to be a traitor of the Holy Church. By the way, in the act [of my entry into the duties of locum tenens] there is a remark to the effect that I am bound not to decline from fulfilling the will of Patriarch Tikhon, and consequently the will of the hierarchs who signed the act..., as well as the will of the clergy and believers who have been in communion of prayer with me these last nine years."

Protopresbyter Michael Polsky cites the words of one witness that Metropolitan Peter had secret links with Metropolitan Joseph, who was in exile in Chimkent. Polsky also writes that Peter was freed for a short time in 1935. This fact was confirmed by the Paris newspaper Vozrozhdenie, which said that Peter refused to make concessions in exchange for the patriarchal throne and was again exiled. Another Paris newspaper, Russkaya Mysl' wrote that Peter demanded that Sergius hand over the locum tenancy to him, but Sergius refused.

Vladyka was transferred to the special purpose Verkhne-Ural prison, put in an isolated cell and given the number 114 instead of being given a name, so that no one should know about the fate of the locum tenens.

He came to the end of his term on July 23, 1936, but they did not release him, but prolonged his term for another three years. From this time the conditions of his imprisonment became still stricter, he hardly saw anyone except the head of the prison and his deputy.

On the evening of August 2, Metropolitan Peter asked to have a talk with the head of the prison Artemyev. On the next day, Artemyev made a report in which his deputy Yakovlev called for Metropolitan Peter to be brought to trial on the grounds that he "made an attempt to establish links with the outside world". Then Artemyev and Yakovlev declared that Metropolitan Peter was an "irreconcilable enemy of Soviet power and slanders the existing state structure..., accusing it of 'persecuting the Church' and 'her workers'. He slanderously accuses the NKVD organs of acting with prejudice in relation to him...He tried to make contact with the outside world from prison, using for this person the medical personnel of the prison, as a result of which he received a prosphora as a sign of greeting from the clergy of Verkhne-Ural."

On August 29 / September 11, 1936 there was an official announcement about the death of Metropolitan Peter. On December 145/27 Metropolitan Sergius assumed the title of locum tenens of the patriarchal throne and Metropolitan of Krutitsa—although, as he himself had admitted, the rights of the deputy of the locum tenens ceased immediately after the death of the locum tenens himself, and as Metropolitan Peter had written in 1931, "my removal would bring in its wake the departure also of my deputy, Metropolitan Sergius."

But Metropolitan Peter was not dead. His execution came later: "On October 2, 1937, the troika of the UNKVD for Chelyabinsk region decreed the execution by shooting of Peter Fyodorovich (Polyansky), metropolitan of Krutitsa. The sentence was carried out on October 10, 1937 at 16.00 hours. Head of the UGB of the UNKVD, security forces Lieutenant Podobedov."

He was buried in Magnitogorsk.

(Sources: M.E. Gubonin, Akty Svyateishego Patriarkha Tikhona, St. Tikhon's Theological Institute, 1994, pp. 681-682, 879-86; S. Belavenets, "Obdorsky Izgnannik", Moskovskij Tserkovnij Vestnik, N 13 (31), June, 1990; V. Rusak, Svidetel'stvo Obvineniya, Jordanville: Holy Trinity Monastery, 1986; Luch Svyeta, Jordanville: Holy Trinity Monastery, 1970, pp. 61-62; Protopresbyter George Grabbe, The legal and canonical situation of the Moscow Patriarchate, Jerusalem, 1974; Lev Regelson, Tragediya Russkoj Tserkvi, 1917-1945, Paris: YMCA Press, 1977; M. Spinka, The Church and the Russian Revolution, New York: Macmillan, 1927; Protopresbyter Mikhail Polsky, Noviye Mucheniki Rossii, Jordanville: Holy Trinity Monastery, 1949-56; I.M. Andreyev, Russia's Catacomb Saints, Platina: St. Herman of Alaska Press, 1982; "Vladyka Lazar otvechayet na voprosy redaktsii", Pravoslavnaya Rus', no. 22, 15/28 November, 1991, p. 5; S. Savelyev, "Bog i komissary", in Bessmertny, A.R. and Filatov, S.B. Religiya i demokratiya, Moscow: Progress, 1993; Alexander Nezhny, "Tretye Imya", Ogonek, no. 4 (3366), January 25—February 1, 1992; Hieromonk Damaskin, "Zhizneopisaniye patriarshego myestoblyustitelya mitropolita Pyotra Krutitskago (Polyanskogo)", Vestnik Russkogo Khristianskogo Dvizheniya, no. 166, III-1992, pp. 213-242; "Novomuchenik Mitropolit Pyotr Krutitsky", Pravoslavnaya Rus', no. 17 (1518), September 1/14, 1994; V.V. Antonov, "Lozh' i Pravda", Russkij Pastyr', II, 1994, pp. 79-80; M.B. Danilushkin (ed.), Istoria Russkoj Pravoslavnoj Tserkvi, 1917-1970, St. Petersburg: Voskreseniye, 1997, pp. 206-209)

From Orthodox Life (Holy Trinity Monastery, Jordanville, New York). Reproduced courtesy of Orthodox.net.