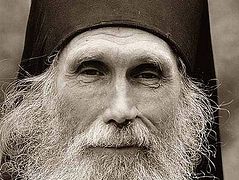

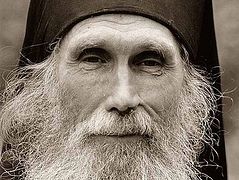

Today is the fortieth day since the repose of Russia’s beloved elder, Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov). The following recollections of him written by a spiritual daughter were posted by Pravoslavie.ru (Russian) on October 8, 2015, the day of St Sergius of Radonezh, on Fr. Kirill’s 96th birthday.

I saw Fr. Kirill lose his inner equilibrium only once.

It was the 1990s. He received people coming to Peredelkino (mostly spiritual children and monks) for confession at the baptistery and, it goes without saying that, on a wave of interest in the revival of Church life, such large receptions became the object of idle journalistic curiosity.

I remember the day when, quite upset and agitated, Batiushka literally darted across his cell from the window to the door and back again, while on his couch lay some foreign object, like a stray bird of prey, spreading its rustling wings, the new issue of “Komsomol Pravda…”

I won’t name the article or author, but I’ll never be able to forget the disbelief and grief of my spiritual father.

Actually, the article was meant to be friendly—certainly not in the spirit of those devastating atheist articles that Batiushka’s generation had gotten used to. I am certain that had the article been deadly, it would have evoked nothing but a smile from Fr. Kirill.

But it was a bush-league encomium, written by a journalist with an unsophisticated and glib mentality in which the confessor of the Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra and some Bulgarian faith-healer Vanga existed on the same order of things. In fact, it was a profanation of true ecclesiality.

“Come to Peredelkino, and you’ll be happy here!” These eight words betray the general sentiment, and, if I may say, deeper meaning of this journalistic endeavor.

“What nonsense! How could they?!” lamented Fr. Kirill, going over to the window, shrugging his shoulders, perplexed. Never before and never since have I seen him so saddened.

Father was justifiably agitated: The article received so-called “public resonance,” and a flood of people gushed forth seeking an easy path and miraculous messages.

There were, of course, among the onlookers just humble, pitiful, and distraught people. He pitied them. He wanted to help them. There were many of them.

And to all of us nuns, working at our obediences in Peredelkino and having seen the growing crowds of people at the baptistery door, this process seemed quite natural. We even rejoiced for the people. Maybe for some this fuss truly turned into a blessing…

Much later came the understanding of how long and hard your own work on the cultivation of your soul must be so that an experienced spiritual father would be able to finally help you in full. This cannot and should not happen immediately after reading some article in “Komsomol Pravda” and a quick hop onto the nearest train from Kievsky Station.1

To get through to someone, to work your way into his heart through all the clutter of his “opinions,” passions, self-justification, and irresponsibility is a work of many years, demanding incredible patience. And the person himself must be willing.

But people wanted simple visible and tangible things: that their husband quit drinking, that all would go well at work, that their children would grow up healthy and that there would be something to feed them.

What can you say here?! Life was never easy for Russians, and people were rife with sorrows in the 1990s.

Fr. Kirill endlessly pitied the people, but did not pander to ignorant attitudes towards the Church as a place of some magic deliverance from sorrow and life’s burdens.

“Love to read the Gospel!” was his most famous pastoral advice, which to many may have seemed too simple, but in fact it called them to a colossal inner work.

Today, mentally returning to those years, I ask myself the usual question: HOW? How did he handle such a load? Where did he get such strength and patience from? After all, this new period in the Church’s life drew this sickly batiushka literally into a whirlpool of the searches and experiences of so many people, who, as they said then, were only seeking the path to church.

And the answer becomes obvious: He did nothing of his own strength.

Everything that happened around him and demanded his participation was all found in Divine power, and only Divine intervention permitted and managed it all. Fr. Kirill turned out to possess adamantine modesty and humility.

This simplehearted and sincere realization of his own inadequacies, his own smallness and insignificance was always felt in this vivacious and outgoing batiushka with amazing clarity.

However, he had no fussy self-deprecation—he simply calmly and honestly did not consider himself an elder, much less one clairvoyant. To receive the people for Confession and conversation was his monastic obedience, which he had to bear with love and hope, seeking strength from the Lord.

Sometimes I was surprised by the degree of inner freedom with which he was able to persuade his visitors of his mediocrity. Visitors were sometimes hoping for something more than just Confession. They were anticipating, for example, that just as in various patericons and biographies, Batiushka would suddenly grab them and reveal to them the secret sins of their youth or announce future events. But before them meekly sat a compassionate priest-monk, who with a peaceful smile would say that he “was unable to bring any benefit—only to receive people at Confession.”

Some left, disappointedly grunting: “He said nothing like that…” while others, caught in the web of this evangelical meekness, began to slowly understand: the answer was somewhere close.

These were lessons from real life—a life in which all self-promotion and feigned significance and every desire for wonderworking are rejected, as trying to shield the quiet radiance of true spirituality; a life which itself allows the light of transfiguration into itself, needing only to take its first step towards the Gospel.

After all, life is one continuous daily miracle!

And I must say that for us, the monks and nuns gathered in Peredelkino in various years from various monasteries, to remain in such close proximity to the confessor of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra brotherhood was a true gift!

Detached from our home monasteries, we often saw the elder; we observed how reverently he carries himself with people; how he prays, not standing out among others; how tremulously he preserves peace and tolerates others’ shortcomings; how he manifests an obedience and humility that you won’t find in any novices… He didn’t teach much, and he didn’t admonish much—he just lived according to the Gospel.

The years passed. The reliable batiushka became more and more weak and exhausted form the flood of visitors. He gratefully accepted the invitation of His Holiness Patriarch Alexey, as he already regularly visited Peredelkino from the Lavra, and had his own cell there, where they awaited him and where he could allow himself a more merciful daily routine. However, the convenience of this routine was aimed at just one thing—the chance to more often remain alone with his beloved Gospel, devoutly and attentively reading the word of God. The rest of his life in Peredelkino differed little from his life in the Lavra: Confession, Confession, Confession…

Since that time—since the time of our happy stay with Batiushka—the criterion of our assessments of people gradually became their regular, everyday, ordinary lives.

Batiushka managed to conceal himself behind this ordinariness. But precisely in this monotony of his monastic daily routine we learned to discern the true spiritual content of life, its evangelical beauty and wholeness.

As a man of obedience and discipline, he, for example, was never late to the common meals and never made anyone hurry up, intending to go receive people. On the contrary—he almost always joined in the joint clearing of the table and washing of the dishes. He did it so easily and organically, so happily and willingly, that from joy we forgot to beseech the elder not to bother. But any routine work turned into a holiday in his presence!

Whenever we desired to turn to him, he always expressed heartfelt readiness to listen or delicately appointed a more appropriate time. His sociability and kindness created a great miracle of unity and mutual affection—anyone familiar with the monastic life or who has worked on a team understands how valuable that is.

It was embarrassing to speak evil and take offense, or to quarrel and complain in his presence. On the contrary, everyone was somehow inspired in the desire to amend his spiritual condition for the better, and to make peace with all with whom they had occasion to break this peace.

As they told us, the same thing happened in the Lavra. Monks would hurry to his cell after the brother’s trapeza to read their prayer rule together, which was divided up between everyone, so that no one would get offended. They could even knock on his door in the middle of the night, disquieted by their pain and worries, and he would listen and comfort them without fail.

As the brotherhood’s confessor, he always remained a sober, zealous, and at times exacting father, having at the same time the gift of some truly maternal gentleness towards people.

It is no accident that we were unable for so long to get used to his serious illness taking the opportunity from us to warm up under his affectionate gaze, to hear his always balanced and heartfelt word, to feel again and again how his kind hand covers our troubled heads with his stole, and a quiet voice unhurriedly pronounces the absolution.

But he was in no hurry to leave us. He received his sickness as a new ministry, and, as an obedient monk, he’s been carrying this cross laid upon him for twelve years already.2

Serious afflictions, as a rule, do not uncover the most attractive sides of the human personality, but in the case of Fr. Kirill, they were rendered powerless to find any defect.

We never heard a grumble from Batiushka, never a moan of self-pity. While he still had strength, he would invigorate us with a kind joke, and as he was able, expressed concern for those caring for him.

As his life has flowed in simplicity, love for people, and devotion to Christ, so it continues to flow.

He’s probably patiently waiting for us to become stronger, when the Word of God will become for us our sole, unconditional, timeless value.