See The Jewish Trial, Part 2. Son of God, Son of Man

We have arrived at last at the Roman Trial.

If you are Orthodox and you’re preparing for Holy Week I hope you have your Holy Week book ready and a book light if you can’t use a candle when the Church grows dark. Sometimes it’s a little bit hard to juggle your candle and hold on to your book at the same time. And I hope you will be in Church for every service in Holy Week. Some of you wrote to tell me that you have young, young children or babies and that’s why you appreciate this podcast. So maybe you might find it a little difficult to get to every service. Maybe you’ll get someone to help you, like a relative to come and stay with you during Holy Week. I remember we had to do that when our son Christopher was very young, when he was a toddler.

For those of you who are not Orthodox, you may not be aware of it but Orthodox Holy Week is a big commitment. Sometimes it’s two services a day and on Great and Holy Friday it could be three services. We practically live at Church during Holy Week. But the services are amazing. They’re deep and profound. And when the Resurrection arrives there’s nothing more joyous, and we really experience it and feel it. Now with Holy Week around the corner, I’m going to give you an assignment. All I want you to do is stand in Church with your book and have a pencil. Rather than a pen, I’d like you to have a pencil so you can mark your book. I just want you to underline or circle whatever sticks out, whatever strikes you, whatever detail you notice, whatever connections you make as you’re following along with the readings. Not just the Gospels, but also with the prophecies and even with the hymns of the Church, and the prayers of the Church. Every year I notice something new and I understand something more deeply than I had before, so I’m rather curious to know if you have the same experience. So after Holy Week is over, if you feel like it you can write to me and tell me what you may have learned just from that simple assignment.

Now let us begin with our lesson. “In the name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. Illumine our hearts, O Master Who loves mankind, with the pure light of Thy divine knowledge and open the eyes of our mind to understand Thy gospel teachings. Implant in us also the fear of Thy blessed commandments, that trampling down all carnal desires, we may enter upon a spiritual manner of living, both thinking and doing such things that are well-pleasing unto Thee. For Thou art the illumination of our souls and bodies, O Christ our God, and unto Thee we ascribe glory, together with Thy Father, Who is from everlasting, and Thine all-holy, good, and life-giving Spirit, now and ever and unto the ages of ages. Amen.”

Between the Jewish trial and the Roman trial—the lashing

Now, before we get into the Roman trial itself I’d like to briefly talk about what happened between the Roman trial and the Jewish trial that preceded it. The truth is that we don’t know exactly what happened to Christ in that intervening period of time between the Jewish trial, when He was condemned in the house of Caiaphas, and then He was taken probably to the Chamber of Hewn Stones where he was formally condemned by the Sanhedrin, and then immediately to Pilate for the Roman trial. But there was some intervening period of time, perhaps not a long time, perhaps a couple of hours, an hour or two—we’re not really sure.

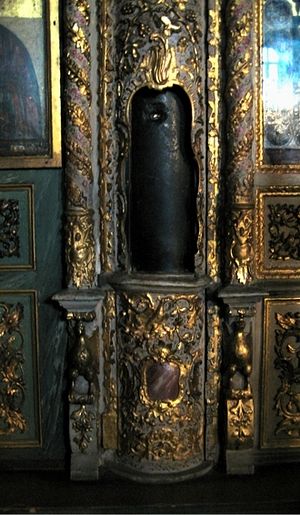

The fragment of pillar (or column) where Jesus was whipped, in the episode of the Flagellation in the wall of Hagios Georgios (Patriarchate) Church, Istambul, south side of iconostasis. Photo: Wikipedia

The fragment of pillar (or column) where Jesus was whipped, in the episode of the Flagellation in the wall of Hagios Georgios (Patriarchate) Church, Istambul, south side of iconostasis. Photo: Wikipedia Let me tell you what was standard procedure for a condemned Jewish prisoner. It was typical for a person who had been found guilty of a crime under Jewish law to receive a lashing, or what might be called a flogging. We would call a whipping. This was different from the scourging that Christ would receive from the Romans. When we get to the Crucifixion, I’ll talk to you about what a scourging was. But a flogging was something that St. Paul tells us he received. He said five times he received “the forty lashes minus one.” This was the whipping, with a smooth whip made of calf skin. In other words it was one strand, like you might see in the movies—that kind of a whipping. It would make a clean mark across your back. And the reason I think Christ might have been subjected to this is because of the fact that we know, having done an excavation underneath the house of Caiaphas, that there was a little cell; it’s kind of strange to imagine. He had a cell in his basement and a little tiny window that allowed a jailer to look in on the cell. In another room next to that cell, in the room where the jailer would be present, there was a pillar. We know that they tied prisoners’ hands over their heads and would lash them to that pillar, and administer these kinds of whippings, which were common under the Jewish law. And, as they would whip them, they would recite verses from penitential psalms, such as, “Have mercy upon me, O God, according to thy great mercy, and according to the multitude of Thy tender mercies, blot out my transgressions”—and give them a lash. “Wash me thoroughly from my iniquities and cleanse me from my sins”—another lash. It’s ironic to imagine the Lord hearing such verses and being lashed by the Jews.

If St. Paul was flogged I think it’s very likely that the Lord was also lashed, and the reason why I think of this—and I tend not to speculate about things that are not specifically said in the Bible—but the reason why I think He may have been lashed by the Jews is because Christ did not last very long on the Cross. He was only on the Cross for three hours. This was considered a very short period of time. People didn’t usually die from crucifixion, as you can tell. The two thieves who were crucified with Him had to have their legs broken. When we get to the Crucifixion I’ll tell you why that was done. But the point is, that when they go to ask for the body of Christ, Pilate is surprised to learn that He is already dead. And this tells you, in my estimation, that He received a very severe beating certainly from the Romans, and also possibly from the Jews; although this is not reported. I think it could have happened, that they also whipped Him before the scourging took place by the Romans.

Now let me just tell you momentarily about the 39 lashes and why is this done. It is part of the Jewish law that you could administer 40 lashes. They would stop at 39, because if a person administered more than 40 lashes, let’s say, 41, and the person who was whipped happened to die from his injuries, the person who gave 41 lashes would be liable for their death because they violated the law by giving 41 lashes—more than the limit. So to make sure that they did not violate the Law this is why they gave someone only 39 lashes. You will notice, if you follow carefully in your readings of the Roman trial, that the number of floggings the Lord received is not specified, so we do not know how many times he received a lash from the Roman floggers.

Before Pilate

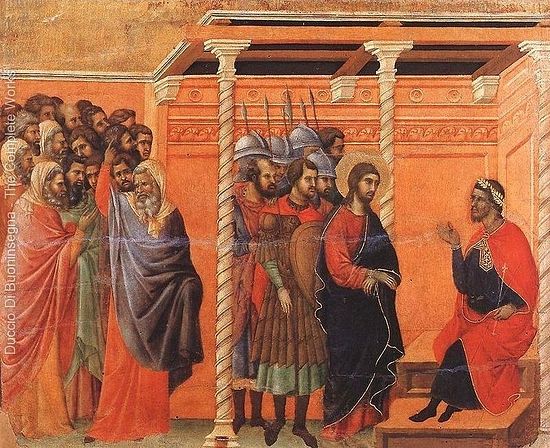

Duccio Di Buoninsegna. Pilate's First Interrogation of Christ.1308-11. Photo: ducciodibuoninsegna.org

Duccio Di Buoninsegna. Pilate's First Interrogation of Christ.1308-11. Photo: ducciodibuoninsegna.org Now let’s read the text in Matthew of the Roman trial. This is Matthew 27:1-2 and then verses 11-26. The verses I’m leaving out have to do with the suicide of Judas.

When morning came, all the chief priests and the elders of the people took counsel against Jesus to put him to death; and they bound him and led him away and delivered him to Pilate the governor. Now Jesus stood before the governor; and the governor asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” Jesus said, “You have said so.” But when he was accused by the chief priests and elders, he made no answer. Then Pilate said to him, “Do you not hear how many things they testify against you?” But he gave him no answer, not even to a single charge; so that the governor wondered greatly. Now at the feast the governor was accustomed to release for the crowd any one prisoner whom they wanted. And they had then a notorious prisoner, called Barabbas. So when they had gathered, Pilate said to them, “Whom do you want me to release for you, Barabbas or Jesus who is called Christ?” For he knew that it was out of envy that they had delivered him up. Besides, while he was sitting on the judgment seat, his wife sent word to him, “Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much over him today in a dream.” Now the chief priests and the elders persuaded the people to ask for Barabbas and destroy Jesus. The governor again said to them, “Which of the two do you want me to release for you?” And they said, “Barabbas.” Pilate said to them, “Then what shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?” They all said, “Let him be crucified.” And he said, “Why, what evil has he done?” But they shouted all the more, “Let him be crucified.” So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man's blood; see to it yourselves.” And all the people answered, “His blood be on us and on our children!” Then he released for them Barabbas, and having scourged Jesus, delivered him to be crucified.

Now in each of the four Gospels there are different details regarding Christ’s Passion. The Evangelists omit or include various details. When the Fathers talked about the Passion they didn’t confine their comments only to the details in the Gospel text in front of them, but they incorporated and commented on other details found in accounts of other Evangelists, and I’m going to include some of the comments made by the Fathers in details found, for example, in the Gospel of John especially, because in the Gospel of John the trial before Pilate is more lengthy and I will mention occasionally some of those details as well.

“When the morning came.”

Now let’s start with this first verse: “When morning came, all the chief priests and the elders of the people took counsel against Jesus to put him to death.” Remember I told you that this seems to be repetition of what we already know had happened the night before. Here it says “when the morning came,” so it seems that the Jewish trial, what I have been calling the Jewish trial, was not the official, the formal Jewish trial. The official Jewish trial happened in the morning. It was a mere formality because they had found all of the evidence they needed the night before when they had questioned Him, so it was a done deal by the morning. But even then if we consider the Mishnah to be an accurate recollection of the Jewish law during the first century, and many people think it is, even the morning trial would have violated Jewish law.

How the Roman Empire was run

Verse 2 tells us, “They bound him and led him away and delivered him to Pilate the governor.” Now Christ was arrested and put on trial in the Roman province of Judea. Not Judah; Judah is the name of this area in the Old Testament. By the Roman times, the Romans called this “Judea,” so learn how to distinguish between Judea and “Judah,” which was the Southern Kingdom during the Old Testament period. In the Roman provinces there were many different kinds of people of various legal status and citizenship. There were different kinds of laws operating depending upon whether you lived in a free city. Not all cities were free. Some were independent cities, like the Decapolis. Sometimes you hear about this region, which is east of the Jordan River. Decapolis means a region of ten independently governed Greek cities. There were also Roman colonies. When I say that they’re “independently governed” I don’t mean that they’re not under Rome, because Rome is running things. I meant that they were left to run their own affairs so long as they paid their Roman taxes and behaved themselves. In the towns and cities there was a considerable degree of self-government. There were also allied kingdoms. You have in Galilee a king, Herod Antipas, who pretty much had unfettered independence. He administered his kingdom as he saw fit, again, so long as he did not conflict with Rome and collected the Roman taxes.

In the provinces the situation was different. A “provincia” is the Latin word for “province” and it literally meant the “sphere of action of a magistrate.” Roman provinces were under the jurisdiction of a single magistrate and that was the provincial governor, whose responsibility included a variety of things including military activities. He was to administer the province. He was responsible for judicial decisions, etc. Governors were empowered to do everything within a province that the emperor could do, and this authority was called their “imperium.” You can see how much that sounds like “emperor” or “empire.” The imperium was the supreme administrative power within a specific territory. The governor commanded the territory by virtue of this imperium, which he received from the emperor himself; the governor could only exercise his imperium within his own province, and only during his tenure as the governor of that particular province. When he was replaced by a successor, then the former governor could no longer exercise his imperium. We’re speaking here of the period of time known as the Roman Empire. Rome was not always an empire. Prior to the reign of Caesar Augustus, Rome was a republic and things were done a little bit differently, although the first provinces are created when Rome is a republic. Now we are in the Imperial period; sometimes the laws were a little bit different, and they continued to evolve.

Although a governor had sweeping powers, these powers were not entirely unlimited. First of all, there were rules that he had to follow. He was not supposed to abuse his power, and if he did, he could be removed or he could be criminally prosecuted for abusing his power. But nonetheless, abusive power, extortion and corruption by provincial governors were a serious and continuing problem throughout the empire. I told you last time about how Caiaphas would have received the right to serve as the high priest by bribery, basically by paying off Pilate, and this was a continuing and serious problem within the empire.

The governor was responsible not only for the administration of criminal justice, but also for civil cases as well. If you had a contract dispute or a theft, etc., you would have come before the governor. Now we can’t really know for certain how many private lawsuits and also criminal prosecutions a provincial governor heard every year, but dispensing justice was a big part of his job, and very often he spent many hours every month listening to cases. Sometimes the governors couldn’t handle all of the cases and they would delegate this judicial function to lower ranking officials. They would also go on what was called assize tours in which they would tour the province and hear cases.

One thing that was the absolute authority of a governor was called the ius gladii, which means, “the right of the sword.” This means that the governor had the authority to execute anyone in his province, which means to put them to death, to administer the death penalty. This power of life or death extended to absolutely every person within the province, whether he was a citizen or not. The governor could execute a Roman citizen as well as a non-citizen, although there were different standards that applied to Roman citizens.

Now, you might think that anyone living in the Roman Empire was a citizen, but in fact, relatively few people were actually Roman citizens. It did not have to do with where you were born or where you lived, but rather Roman citizenship was a status you inherited. You could purchase it, if you had enough money, or you could acquire it perhaps by giving outstanding service to the empire. Only about ten percent of all of the people living in the Roman Empire were citizens. The rest were called “peregrine,” or “foreigners.” Isn’t it ironic that you could be living in Judea and be a Jew, and yet the Romans would call you a “foreigner” in your own land because you did not have Roman citizenship? Roman citizenship was very highly prized—and it was not only an elevated status, but it also gave you certain rights, protections, and privileges, especially in a criminal proceeding. First of all, citizens were given much better treatment. You could not be crucified if you were a citizen. And we know, of course, that St. Paul, being a Roman citizen was not crucified but beheaded. That doesn’t sound so great to us, but it’s a lot better than being crucified.

St. Paul inherited his Roman citizenship from his parents, but we don’t know exactly how they became Roman citizens. It was very rare for a Jew to be a Roman citizen and I won’t waste your time by speculating about some of the theories that people have about how Paul’s family had become Roman citizens. But we see in the book, the Acts of the Apostles, how Paul used his citizenship very effectively. They would arrest him, seeing that he was Jewish by his manner of dress, they would beat him up and rough him up, throw him into prison without any kind of what we would call “probable cause,” without following the proper procedures for a citizen. And then he would say, “Oh, you know, by the way I happen to be a Roman citizen.” Then you see how the jailors would react, how fearful they would become, because they had mistreated him and he had the Roman citizenship. So it gave you certain protections, especially against being tortured, beaten without trial, etc.

Provinces in the first century did not have a police force or professional prosecutors. Some of the things we would consider a crime, for example a theft, was not a crime under Roman law. Roman law was very, very narrow, and if someone committed an offense against you it was considered a personal offence. For example, if someone stole something from you, that was called a “delict.” It was not a “crime.” It was a personal affront, and if you wanted to prosecute the person whom you believe had stolen from you, you had to go identify the suspect; you had to arrest him, literally go and grab him yourself, drag him before the magistrate and prosecute the case. This was a lot of work. But we see that this is the function the Sanhedrin performed in the case of Jesus. First of all, Jesus has not committed a crime under Roman law. He has claimed to be the Son of God. That’s not a crime under Roman law, but we see that the Sanhedrin has performed the function required by Roman law—they accuse Him of a crime, they have arrested Him, they have done their investigation to find evidence with which they could accuse Him or prosecute Him, and now they’re bringing Him before Pilate.

The Romans encouraged self-administration and they respected local laws and customs. They liked the fact that these various provinces were pretty much running themselves, because it would have been impossible for the Romans to have the hands-on responsibility of running these vast areas. So they expected that the Jews would administer their own affairs.

How the Jewish leaders convince Pilate to crucify Christ

Now the Jewish leaders brought Christ before Pilate because they determined that He deserved the death penalty, right? In St. John’s Gospel it tells us exactly what they said to Pilate: “Under our law He has to die because He has made Himself out to be the Son of God.” You see, they tell him that, but it is not a violation of Roman law, and just like today if you are going to be put on trial for a criminal offence, you must have violated the law. Somebody can’t say, “I’m going to put you on trial because I don’t like your personality,” or “I don’t like your tie,” or “I don’t like the way you raise your children.” If you haven’t violated a law, you haven’t committed a crime. This is the first problem the Jews face: They have to find a violation of Roman law by Jesus.

The other challenge they have is that they do not have the right to actually exercise capital punishment, and, of course, this is what they want. They’re taking Christ to the Romans for trial and they want Him to receive the death penalty, so they must have a charge that is serious enough to warrant death. In addition, of course, they want Him crucified, because they want to totally disgrace and discredit Christ and His movement. This is the number one reason why they want Christ crucified—because, the truth is, if the Jewish leaders simply wanted Him dead, they could have taken Him off for a long ride in the country, fitted Him with a pair of cement shoes, and thrown Him over a cliff or into the ocean or something like that. So they don’t just want Him dead, they want Him crucified. They want Him completely disgraced and discredited, because under Jewish law it said that “a person who hangs on a tree is cursed by God.” This is Deuteronomy 21:23. Crucifixion was considered a form of hanging; and by the way, that’s why the Cross is sometimes called “the Tree,” in case you ever wondered.

So under Jewish law somebody who hangs on a tree is considered cursed by God. Once they succeeded in crucifying Christ, forever to this very day, Christ is considered cursed by the Jewish people. The manner of His death remains the number one reason why even today Jews do not believe He was the Messiah. This, above all things, is the reason why Jews today will say Christ cannot have been the Messiah, because God would not allow His Messiah to be crucified. He was cursed by the Law.

So the Gospel of John tells us that they had led Christ from Caiaphas to the Praetorium. That detail—exactly where Pilate was—is not mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew. And also the Gospel of John tells us that it was early morning. Now the Praetorium was the Roman quarters. Pilate would not have spent much time in Jerusalem. Most of the time he was in the Roman capital, the magnificent city by the sea that Herod the Great had constructed called Caesarea Maritima. This was, as I said, the Roman capital. But he would come to Jerusalem as was necessary, especially during the Passover, as I mentioned, because of the tensions during that week. The Praetorium was the Roman governor’s headquarters and residence, and it was located in the Antonia Fortress. This was a fortress which had been built also by Herod the Great and named for Mark Antony, and it was located in one corner of the Temple Mount, overlooking the courtyard of the Gentile. That courtyard was a huge gathering place, which surrounded the Temple building itself. That’s where the Roman soldiers were quartered, and that’s where they were keeping an eye on the large crowds of Jews who would gather there in the courtyard for various festivals, etc. And of course, as I mentioned, St. John’s Gospel tells us that the Jews brought Christ to Pilate for His Roman trial early in the morning. This was not an exaggeration; the Romans liked to begin their business very early in the morning. It was not unusual for them to start their working day at 6 am, or the crack of dawn, and to be done by noon. The Jewish leaders knew this so they had a perfunctory Jewish trial and took Him straightaway to Pilate. They also would have wanted to finish early because that day was the eve of the Passover. It was a very, very busy day, it’s like Christmas Eve—it’s an extremely busy day for everyone. John also tells us in chapter 19 of his Gospel that the Jewish leaders themselves did not enter the Praetorium, “lest they be defiled, that they might eat the Passover.” So if they were to set foot inside the residence of the Roman governor they would be defiled, ritually defiled, and would not be able to remove their defilement by ritual means prior to the start of the Passover. Chrysostom has a wonderful comment on this. He says “They who paid tithes on mint and anise did not consider that they were defiled by becoming murderers, but thought that they defiled themselves by merely entering the court of Pilate.”

Were only the Romans guilty?

Let me just take a moment at this time to comment on one aspect of the Gospels, and that is Pilate’s reaction to Christ and the criticism which I have heard about the accuracy of the Gospels in this regard. This came up again a few years ago when the movie “The Passion of the Christ” was released. Many Jewish people were very apprehensive about the release of the movie, and understandably so, because they have been blamed historically for the death of Christ and they’re very sensitive about this. However, in this regard they basically were saying that they had nothing to do with the death of Christ. It was entirely the fault of the Romans, and the Gospels were not accurate because Pilate was not known as a soft-touch, let’s just put it that way—Pilate would not have given a second thought to executing someone such as Jesus. Well, it is true that Pilate was a very hard man, that he had had many people executed. There is no doubt in my mind that had he thought that someone maybe was not even certainly guilty of treason, but only possibly guilty of treason, that he would not have hesitated to have that person put to death. But at the same time I found it rather difficult to believe that even a hardnosed person such as Pilate—who had a very tough job running Judea, and understandably had to be very stern, very severe—that he would willingly and knowingly put an innocent man to death if that was not necessary; here he was basically forced to do so. I think that the Gospels are accurate. I think that Pilate realized that Jesus was not guilty of any crime. I think that it was in many respects quite evident by the fact that Jesus was standing there by himself, completely alone. What was he going to do, overthrow the Roman Empire by himself? Where were the people who were His conspirators? Where were the weapons? Where were the plans? There was nothing to support a charge of treason against Christ, and that, coupled with the fact that Christ stood before Pilate with such dignity, with such grace, not fearful, not begging for His life—what an impression this must have made on Pilate! And him also knowing the character of the Jewish leaders and them finally confessing that they brought Him before Pilate because He claimed to be the Son of God, I don’t think it’s so farfetched to believe that Pilate really did not want to execute Christ. So I stand behind the Gospels. I believe that they are accurate in this regard.

Many people say, “The Evangelists wanted to paint Rome in the best possible light and put all of the blame on the Jews.” I don’t think that’s true. I don’t think the Evangelists were trying to curry favor with Rome. I don’t think that was necessary, because when these stories about the traditions, about the Passion of Christ first circulated (because these stories were told orally first before they were written down in the Gospels and everyone knew the stories) Christianity was not illegal. There was no reason to curry favor with Rome by painting Pilate in a good light and painting the Jews in a bad light. I don’t think that was necessary, so there’s nothing really to support the view that the Gospels are historically inaccurate. Even though Pilate was a very tough man, I still think that most people are unwilling to put an innocent person to death; and that was the case here.

Now before we continue with our discussion about Pilate let’s pause right here and we will continue our lesson on the Roman trial in the next installment.

Presbytera and Dr. Jeannie Constantinou’s podcasts can be found here.