Today, after the church has been cordoned off, traffic will stop, the procession of the cross will start shortly and vehicles will have to go around the church. Thirty-five to forty years ago, during the Soviet era, the police put cordons around churches to keep out the faithful. Even those who managed to break through them couldn’t receive Communion at the midnight service.

Professors of the Moscow Theological Academy Archpriest Maxim Kozlov and Alexei Nikolaevich Svetozarsky spoke in this interview for Tatiana’s Day about the fears and joys of the Paschal nights of thirty-five to forty years ago, the “springtime cakes,” and “Saturday community unpaid cleaning days” (in Russian: subbotniki).

A procession of the cross, the 1970s.

A procession of the cross, the 1970s. Alexei Svetozarsky: If you wanted to get into a church before the Paschal service you had to fool the so-called “public order volunteers,” or “police helpers” (in Russian: druzhinniki), who in fact were workers of the Komsomol District Committee. One year I noticed that they had special Komsomol membership badges with gold-colored branchlets—the so-called “Lenin badges”. Ordinary people did not have these—they were distinctive marks of being an activist, a professional Komsomol worker.

You needed to walk past them with unfaltering steps, pretending to be going past the church, and then right near the fence abruptly turn into the gate and dart through. It should be said that this was rather easy, and they did not throw their weight about on the church’s territory—it seemed they followed somebody’s directions. They certainly did not disturb anyone inside the church, but in the courtyard they would start barking: “We will show you a work-off!” But these were empty words as they had other events planned after that. They celebrated the feast in their own manner, too, and did it in a big way.

Those supervising worshippers, the 1970s.

Those supervising worshippers, the 1970s. Or we could lull their vigilance by walking down a lane (as a rule Moscow churches were built in lanes), making them believe—whistling and looking in every direction—that we were just strolling about. And we needed to do it at ten or even nine in the evening because at eleven you didn’t have access to the church. But if a priest knew you well, he could come to the cordons and ask them to let you pass—then they would let you in.

“One bitter moment stuck in my memory. I was at one parish church on Pascha; it was the time when I became aware that I was a Christian. Perhaps I was still uncomprehending and inexperienced, but by that time I had entered into Church life, I felt a sense of belonging and unity of people who gathered at church. I was astonished that a local priest refused to help my friends through the cordon. I reached the church’s courtyard, while my companions were standing behind—they had lingered and thus were late. There were only two of them, but they came there not just to stare at others… And they were not let in. So I managed to go through the line and asked the priest to help me, taking his blessing. But the latter refused: “Yes, I see that you are from our parish, but I don’t know who those guys are. I am in charge of my own parishioners only,” he said. It was very disappointing, although now I understand that priest very well.

Archpriest Maxim Kozlov: When they did not let you in they explained it by the fact that a large number of odd idlers were walking around, and it was the task of the public order volunteers to protect us from these gawkers and hooligans. But in reality their aim was to deny young people access to church. That is why it was necessary for young believers not to be timid and confused. They were to walk very confidently, demonstrating that they knew perfectly well where they were going.”

A girl at a church, the 1970s.

A girl at a church, the 1970s. “I have come to the church for a service.”

(They could not do you any harm in the yard but could come up and talk).

“Really? It is Interesting? And where do you study?”

“It’s not your business,” I reply, at the same time worrying not so much about myself as about my parents, because I could greatly distress them, to put it mildly. But I was a hotheaded youth and could not back down. And they promise: “We will wait till the end of the service all the same.” True, the festivities sometimes were overshadowed, but these police helpers never waited until the end of the service.

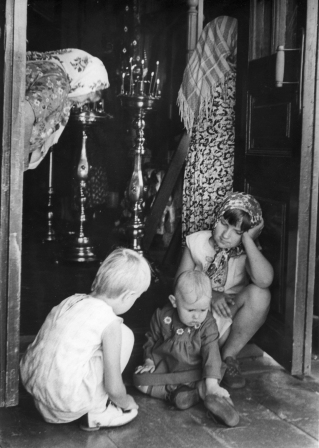

Children on the doorstep of a church, the seventies.

Children on the doorstep of a church, the seventies. Fr. M. K.: I remember we all were gathered in the altar on Pascha when the vestments were blessed. We looked forward to this day, although we did not know if they were going to invite us, so we were concerned.

They took us under their wing and protected us. We stood through the Pascha Vigil and the Divine Liturgy all together, I even remember the entrance hymn that Fr. Nicholas sang; my memories are still very vivid. The atmosphere was unspeakably solemn. For some reason, we felt indescribable joy at this church In Obydensky Lane, although it was packed with people.”

A. S.: Earlier I had visited other churches on Pascha. I always liked the church in Sokolniki very much—the church itself was very bright, with a joyful Paschal atmosphere. I attended the Pascha midnight service there on two occasions. I couldn’t get to the Yelokhovo Cathedral of Theophany because in order to enter it you needed a ticket.

Fr. M. K.: There were two churches where tickets were required for entry on Pascha. This fact was caustically noted in the Soviet comedy, “The Blonde around the Corner.” These churches were Yelokhovo Cathedral and Novodevichy Convent. Some entrance tickets were spread through Church circles and the remainder, by mysterious ways: to powerful people—the Soviet intelligentsia, tradesmen, and the Kremlin’s service staff; that is, doctors that served the Kremlin administration and so on. The bog fish in Soviet trade formed a hidden elite. At that time it was considered a bit of a shame to work in commerce, but the “right people” knew where money was made.

A. S.: Tickets were also used as commodities and could be exchanged for something else. Recently I found one such ticket; I am going to bring it to the Church Museum of the Twentieth Century when it opens.

Fr. M. K.: The public order volunteers, of course, never waited until the end of the service. By that time there was nobody around. You could freely get into the church at one o’clock. After the procession of the cross, those who were not permanent parishioners left the church and were followed by many others during the Paschal Vigil, especially towards its end. It was due in part to the problems with transport at that time, and not everybody knew when the service would end.

In those days, almost nowhere did believers receive Communion on Pascha. They would have taken Communion earlier—on Holy Thursday or Saturday. There were thousands of communicants on Holy Thursday in particular. On Pascha Sunday only clergy took Communion. By the way, I never received Communion on Pascha; I knew that it was not done here. Some of the young people who took part in the cross procession in vestments were given Communion in the altar. But it did not apply to ordinary parishioners, so many left earlier. Towards the end of the Paschal services the churches were no longer packed.

A. S.: I have a fantastic Pascha story, connected again with St. Pimen’s Church. It was a very cozy lane there (it no longer exists; it was comprised of charming old Moscow’s two-storied corner houses, which are sadly gone).

There was a cordon between the houses formed by both the police and volunteers. We were delayed, so it was after ten in the evening. To my great surprise, a police major led me through the cordon (it was because our neighbor’s daughter worked at the police department)! I somehow contrived to make a call, so the police major came up and accompanied me.

A church, the 1970s.

A church, the 1970s. It was in the following year that I finally went to my first Paschal service. I was afraid that something would obstruct me and came so early that the church was not cordoned off yet (at about eight in the evening) and Pascha cakes [kulichi in Russian] were still being blessed. The church was empty. So I waited from eight till about eleven. First I stood three hours till the beginning of the midnight service and then through the Matins and the Divine Liturgy that followed it.

In Obydensky Lane, people did not leave the church during the procession. It was so crowded there that only the clergy, the choir and people in vestments, with banners and candles, went outside—many men both young and elderly. The church in Obydensky Lane had a tradition that could not be found in all churches: to take as many people in vestments (all that they had) as possible out, with many-colored candles. There were twenty such pairs in all—it was the maximum that the altar could accommodate. It was a real cross procession.

One’s first Pascha is an amazing feast. I had never imagined that an experience like this was possible. Now the times have changed. So many years have passed and my self-perception has considerably changed, and my role in the Liturgy is now very different; but it can be said without exageration that it was heaven on earth. It was something fabulous.

Then I was with my sister, and we did not stand through the whole service. It was natural that we, together with most of the worshippers, left towards the end of the canon, after the Paschal stichera. It was something very special, too; it was the only Moscow night of the year when, as you walked in the dark, you met like-minded, Orthodox people. You could say, “Christ is Risen!” seeing other passers-by on that Paschal night, knowing that they were returning from the churches in Khamovniki, or Filippov Lane in the Arbat or Bryusov Lane, while you would be walking from the church in Obydensky Lane. You exclaim: “Christ is Risen!” and they would answer, “In Truth He is Risen!” That was really “something” in the Soviet Union. One would have to have experienced this in order to understand it.

A. S.: After the Pascha service we used to walk—there was no getting away from it. We would have a bite to eat on a bench (all food was very simple: Paschal eggs and cakes—it was all we had). Once we were going down the escalator in a group to the metro station that was formerly called, “Marx Avenue,” and met a company of girls, who were junior students and played an absolutely different role. They were sent to the cordon near Novodevichy Convent presumably due to lack of responsible workers. We all knew them very well. There was a pause… Suddenly one of the girls uttered, “Christ is Risen!” And we answered, “In Truth He is Risen!”

Regardless of everything, Soviet people knew how to greet each other and what to answer on that day.

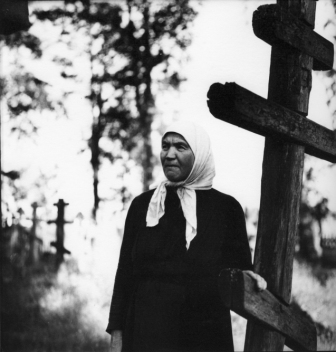

Near a cross, in the 1970s.

Near a cross, in the 1970s. A. S.: Let us also recall our joys during the preparations for Pascha. We always went to the market: Cheryomushkinsky, or Preobrazhensky. On Preobrazhenka craftsmen used to sell wooden eggs—adorned and beautiful. I kept them a long time (maybe several are left somewhere)—I willingly distributed these eggs among my friends, although I had bought heaps of them. And those paper flowers were a pre-revolutionary tradition. On old photographs I have seen Pascha cakes decorated with them, and it was seen that the flowers were made of paper.

Fr. M. K.: All of this is gone. Today there are no paper flowers any more, while wooden eggs have become too “manufactured.” Where is that naivety of ours? We have lost it.

A. S.: In our family Pascha was never associated with the tradition of going to cemeteries. Of course, we did go to the graveyard and looked after our deceased relatives’ graves, but it was not on Pascha Sunday. Deep in our subconscious we knew that Pascha is joy, the festival of both the living and the departed whom we remember and feel as if they were alive. But in the public conscience it (Pascha) was a phenomenon related to the cemetery.

Fr. M. K.: What was the most conspicuous thing about Pascha in the Soviet era? By that season the “springtime cakes” and “Slavic cakes” appeared in baker’s shops. It was a kind of a pseudo-kulich that appeared only at that time and soon disappeared. Also there were films that were intended to attract the youth. During Pascha night all cinemas had some cool Western movie as a late-evening show (from about eleven in the evening, which was a rarity)—an action movie, something with erotic scenes, or a French comedy. On all other days the last showing was at nine in the evening. And during the same Paschal night, Soviet TV showed such famous Western celebrities as Abba, Boney M and other “cool” singers. It was the “coolest” concert ever broadcast by Soviet TV all year.

A. S.: The system was decaying and nearly dead, the spirit was different, and there was nothing one could do about it. The night before Pascha, schools organized parties but everybody could do as he wished: either go to the school party or to church. At ten in the evening all were asked to go home anyway, so it was not even clear why people were invited to those parties.

Fr. M. K.: On paper the system still fought with religion, but in reality they let things slide. For example, they could organize a community day of cleaning. It was a common occurrence: a Saturday “cleaning day” on Holy Saturday! Among the minor “mean tricks” the Soviet government played with us in those years was its desire to organize the “Lenin subbotnik” (timed to Lenin’s birthday on April 22) exactly on Holy Saturday, taking advantage of every possible opportunity to do it. I well remember that in my years at the university I would sign up for a vegetable depot in order to work on some other day—either before or after the feast—and to go to church on Holy Saturday.

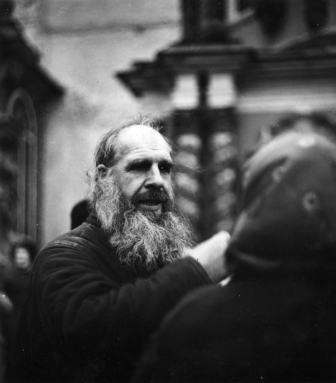

A man, the seventies.

A man, the seventies. I decided not to teach that day, although I had about four lessons according to the schedule. I greeted the children on the feast of the Resurrection of Christ and told them they were free to do whatever they wanted. I already could take the liberty of allowing them this at that time. So they made noise, shouted, drew, threw pieces of paper at each other and so on. I know that this was terribly anti-educational. But something from that lesson stuck in their memory forever. It made an impression upon me. I was not inclined to follow the short story by Leo Nikolaevich Tolstoy, The Candle, where a barin [in old Russia a member of the gentry] forced one of his peasants to plow on Pascha Sunday and the latter placed a burning candle on his plow while he worked. I considered it a grave sin to work on Pascha and celebrated it myself with joy instead of working.

However, the results were quite nerve-wracking. I had a real row with the headmistress, who was a rather young, energetic lady with “right” ideology. But there was a paradox there. If Sundays—when they were working days—fell on days other than Pascha, the same children did come to school. They explained their absence on Pascha by saying, “We were at the cemetery,” or “We were in the country.” And it was clear that their absence could only be explained by Paschal celebrations.

Dreaming on a suburban train, in the 1970s.

Dreaming on a suburban train, in the 1970s. Some churches also held a midnight service during Holy Week, namely the night before Holy Saturday. It was celebrated, for example, at the church in Khamovniki. The church in Obydensky Lane did not have midnight services, while some others did. The Matins with the Lamentations were immediately followed by the Divine Liturgy of Holy Saturday. The latter ended very early, and the blessing of Pascha cakes then began. At that time they blessed Pascha cakes from seven in the morning at this church. This tradition was abandoned, I think, in 1989, because it was too hard to stand through two nights on end. I went to this church for that midnight service two years in succession, or even more. These services were a great delight; but, unfortunately, they did not gather many people. The main reason was transport. Some believers would come from the same neighborhood as the church, while others would come specially to that church from great distances. After two nights people got fatigued, all the more so because Holy Week is a very stressful period with its services, although Saturday was a day off at that time.

Fr. M. K.: Anybody and everybody would come to church to have their Pascha cakes blessed. There were crowds of people, an endless stream of people. When I made friends in the Church they gave me Pascha cakes every year, and later, in the second half of the eighties, we already had our own kulichi, or some of our family friends gave them to us, and I went to have these kulichi and eggs blessed. Each time it was a very special event. I had no basket so I put my kulich into a plastic bag. Religious families baked their kulichi themselves; they kept handwritten recipes. It was important for any church-going person to have not a mere “springtime cake” from a bakery, but a real, hand baked Pascha cake. I remember that I appreciated it very much.

A Pascha cake and a Russian paskha curd cheese, in the 1970s.

A Pascha cake and a Russian paskha curd cheese, in the 1970s. At that time pasochnitsi [traditional Russian wooden molds for making paskha curds] were already disappearing. Our family had a very old pasochnitsa; it had been made by a woodcarver on the pattern of an older one. And when in the second half of the eighties I lived on my own I acquired a pascha mold myself. At that time many people made their paschas in small pots, not in special pascha molds, which were disappearing, and they objectively had nowhere to take them from unless they personally knew a carver who might make it—but that was a rarity.

A. S.: In the fifties and sixties these molds were bought in markets and then became a thing of the past. We bought a new one early in the nineties. Then some cooperative stores opened, so it was bought in one of those small shops. It was a good, classic mold…