I’ve known and worked with Viacheslav Mikhailovich for many years, but apparently I didn’t know the most important thing about him. That’s how it often is—you think you have a good relationship with someone and know him like the palm of your hand. But your own myopia and inattention keep you from looking deeper.

Not long ago, Viacheslav Mikhailovich and I went on a working trip together. It was all as usual: He is an artist, and I am the editor and compiler of a book about a monastery. This time our path lay in Pskov province.

We boarded the Moscow-Pskov train, drank tea, and talked about our plans for the trip.

“Look,” Viacheslav Mikhailovich said as he pulled a small photo album out of his bag. “This is Mila, she’s always with me. I take this album on all my travels so that I can feel even more strongly that Mila is present in all the places where I am.”

Opening the album I saw a magnificent photograph of Liudmila, Viacheslav Mikhailovich’s wife, who died a few years ago. I knew Mila very well, because I would sometimes work in their home. I also knew little about their family history.

Viacheslav and Liudmila were married in the distant 1970s, when they were both twenty years old. They both worked at the printshop. Viacheslav was an artist and book designer, and Mila was an artist and picture editor, and a restorer of old photographs and film. They now have fully grownup children, six grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

When Viacheslav Mikhailovich, during the wild ‘90s, followed his heart and started working for the budding publishing industry of religious literature, their whole family began participating in Church life—profoundly, thoughtfully, and authentically. This even included both their children, who in turn created truly Orthodox families and raised their children as Christians.

I turn the pages of the photo album. Their whole life is in it, from the black-and-white baby pictures to the final days, when the light of eternity was already shining in her eyes—precisely light, not fear, not confusion. Suffering, of course; but the light breaks through the suffering.

“She was so beautiful, Mila!” I exclaimed, returning the album to Viacheslav Mikhailovich.

“Why do you say, ‘was’?” he replies, taking another look at that precious face. “She still is the prettiest, even now.”

Lying during the night on the upper bunk unsleepingly and looking through the window at the darkness, pierced here and there by rare streetlamps, I thought about how just such a love between husband and wife, not subject to death, was to thank for the foundation of the very monastery that Viacheslav Mikhailovich and I were heading towards.

Yes, and this is not usually the case, because monasteries are more often founded by ascetic monks and nuns, and much less often by widows and widowers. It is even rarer that a monastery is founded at the mutual agreement of two spouses. It is thanks to this very love, overcoming all obstacles, that the Tvorozhkovo Holy Trinity Monastery was founded.

Here is how it started.

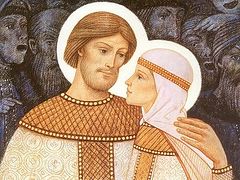

In 1824, a fifteen-year-old girl from a wealthy noble family, Alexandra Shmakova, married out of mutual love a wealthy aristocrat, a russified German of the Lutheran faith, Karl Von Rose. Alexandra was well educated; she graduated from Smolny Institute, and shared with her husband an interest in the cultural trends of that time.

And there certainly was much to be interested in—they read the freshly written masterpieces of Alexander Pushkin, or the comedy forbidden by the censors but circulated in handwritten copies, Griboedov’s Woe From Wit. The Von Rose couple’s contemporaries were the composer Mikhail Glinka, writer Nicholai Gogol, and the poets Mikhail Lermontov and Feodor Tiutchev.

The young couple lived in the capital city of Petersburg—the cultural and political center of Russia. They lived a brilliant life in society, and it seemed that nothing could overshadow their cloudless happiness. But there was one circumstance that gave them no peace—Karl and Alexandra had no children.

Only after twenty-three years of life together was a daughter, Maria, born; but to their great sadness her life did not last long. Without living to age two, the girl died. Understandably, the parents’ grief was inconsolable, and if Karl Andreyevich stoically and manfully bore the loss, Alexandra Fillipovna fell into the darkest despair. She nearly lost her mind, and murmured against God.

But her kind heart did not allow her to perish utterly. In little Maria’s memory Alexandra Filipovna began to do charity work, and the reward for her kindness became a living, fervent faith in Christ that was ignited in her heart. Now society life was uninteresting and dull, and all her thoughts and yearnings were for God and the fulfillment of the commandment to love one’s neighbor.

Although Karl Andreyevich was glad that his wife was consoled, he did not share her fervent religiosity. This seemed to him to be just another extreme—his wife was now spending too much time in church. And despite all her efforts to convert him to Orthodoxy, Karl Filipovich remained a Protestant. Misunderstood by her husband, Alexandra Filipovna wanted to leave for a monastery. She began travelling to monastic communities and getting advice from spiritual people. But no matter who she asked, they all answered that it is not godly for her to leave her husband, and that she must show patience and love for him.

Then Alexandra Filipovna began living a very strict life at home—praying, fasting, and responding with love and meekness not only to her spouse’s criticism but also to the derision of her servants. Her servants considered her abnormal and gossiped that their mistress eats “dog food”, meaning the oatmeal that made up Alexandra Filipovna’s daily ration.

Her prayers and ascetic labors, and mainly, her love and meekness where generously rewarded. Karl Andreyevich finally became Orthodox, with the name of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, whom he had always deeply venerated. And he made this step not simply to please his wife, but rather he turned to the Lord with all his heart and soul.

It was he, Nicholai Andreyevich, who once said to his wife, “Let’s make an agreement that if you die before me, then I will build a men’s monastery; that is, I’ll die to the world, but if it’s my fate to die before you, then you will build a convent. That way we will always be together and never part.”

Of course her husband’s suggestion found the warmest response in Alexandra Filipovna’s soul. It so happened that Nicholai Andreyevich departed first. Not long before his death he took possession of the Tvorozhkovo estate in depths of Pskov province, and the main purpose of this purchase was to prepare a place for a monastery.

Creating the monastery cost Alexandra Filipovna great labors and huge sacrifices. But she fulfilled the agreement she had made with her husband. And the Tvorozhkovo Monastery grew, manifesting to the world that in God and with God, love is stronger than death.

By 1913, over thirty years after the death of its foundress, Nun Angelina—Alexandra Filipovna’s name at the tonsure—Tvorozhkov Monastery had 110 sisters, with thirty orphans in the monastery’s orphanage. The sisters worked fields and gardens, kept cows, and were completely self-sufficient.

After the tragic events of 1917, the Tvorozhkovo Monastery shared the fate of the majority of Russia’s monasteries and churches—it was emptied and crumbled to ruins over the long decades. But, O the wonder! The people’s grateful memory preserved all those years the site of Mother Angelina Von Rose’s burial. The faithful would go there to pray and ask for help, and someone always took care of the grave.

In the early 1990’s, when the convent lay in ruins, several nuns came to Tvorozhkovo and began restoring monastic life there. It would seem that that there could be no hope that the monastery could come back to life in such an unpopulated wilderness. But it was reborn just as it was when Nun Angelina built it in memory of her husband, Nicholas Von Rose.

Now the wheels of the train taking Viacheslav Mikhailovich and I to Pskov are clacking, and from there we will have to travel another 110 kilometers to Tvorozhkovo. In Viacheslav Mikhailovich’s travel bag lay the precious photo album, and Mila, his unforgettable spouse, is of course travelling with us…

In Tvorozhkovo Holy Trinity Monastery the sisters told us that they often receive letters with requests to place a candle on the grave of the monastery’s foundress, Mother Angelina, as a sign of gratitude for prayers answered. It turns out that after prayers at this grave to find a life companion, happy marriages have been formed, and to childless couples who ask for help, children are born.