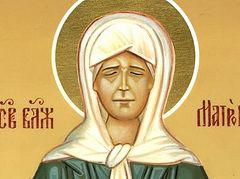

On May 2, 1999, the rite of canonization of the blessed eldress Matrona, ascetic of piety of the twentieth century and national consoler in the atheist years so mournful for the Church, was celebrated before a large gathering of people. This blessed Christ-pleaser shines with a special light amidst the great host of Russian saints standing before the Throne of God. From birth, she was bereft of the ability to see, but she possessed blessed spiritual vision—the gift of clairvoyance.

Do we understand what it means to be blind from birth, to live ever in impenetrable darkness? It’s impossible to escape from it—nothing and no one, and there’s just darkness without end, beyond which is eternal darkness after death. Matronushka was not just blind, but she didn’t even have eyes. Her eye sockets were tightly covered by closed eyelids, like that white bird had that her mother saw in a dream before her birth.[1]

In the sixth week of Pascha, on the Sunday of the Blind Man, we hear the Lord’s explanation of the meaning of Blessed Matrona’s sufferings. Who sinned—he or his parents? the Lord’s disciples anxiously ask about the man blind from birth (Jn. 9:2). All troubles are associated with sin; even earthquakes, floods, and droughts are from our sins, and there is a mysterious law of justice, according to which punishment from sin reaches unto the third and fourth generation, but the mercy of God upon a saint extends unto a thousand generations. However, this law is always hidden and mysterious, and we should beware of making straightforward conclusions. It’s not without reason that the Ecclesiast laments that so often the righteous endure affliction, while the wicked prosper. This is a sticking point for many, not just for yesterday’s professional atheists, denying the existence of God because of the terrible suffering and injustices in the world, although in their outrage itself you can sometimes see a good blindness—an unconscious yearning for God; our desire for perfection and a higher justice is already the light of God within us.

Neither hath this man sinned, nor his parents: but that the works of God should be made manifest in him, says the Lord (Jn. 9:3). It doesn’t mean that anyone is born sinless, but that God is infinitely merciful. The story of Righteous Job the Longsuffering is a testimony to this mystery. The same fully applies to Blessed Matrona. The highest providence of God is communion with God, and this relates to the path of man beginning from the very depths of birth. “God punished him”—and the indifferent people surrounding him judge him immediately, not seeing that the Lord visited him, or, in other words, looked upon him with a special love. As Blessed Augustine says, we see because God sees us. God sees us, and He wants us to see Him.

One seriously ill young man told me about how in his childhood he was a pious boy, often going to church, and how he was given to know grace, as the mercy of the Lord. But then a tragedy occurred with him: He fell out of a tree and was permanently paralyzed. At first it was unbearably awful—he was big and strong, and shame and anger simmered within him. Throughout the months he reviled God. Then, through prayer he came to understand what had happened to him. Once he said to himself, “Before this accident I knew that God loves me, so what has changed now? And gradually he began to understand everything. It became completely clear to him that God had personally touched him and that He wants to say something to him through this disease. He prayed to enter into the mind of God, into His providence for him, and to see that he suffers not in vain. The sins in which he lived began to be revealed to him. He had to recognize them—that’s what expelled him from God. Perhaps someone will ask what special sins could a young boy have? But we know that in drawing near to the light of Christ, the saints all the more were able to see their own sinfulness. Sometimes he would say to the Lord, “If I, being healed, would again begin to withdraw from Thee, I prefer not to be healed,” and therefore even death was not fearful for him. In the end, such a thing is not a true evil, but gives us the possibility to go to God.

If we knew, says St. Seraphim of Sarov, what it means to see God, we would agree to walk through any darkness to get to Him. Sufferings may be different, but the worst thing is the fear that you will forever lose the Divine light because you no longer feel any connection with God. Many think the path to God is all light, peace, and joy; but God, having once vouchsafed us to see light, tests the soul. It’s one thing to accept God in His personal revelation, with joy and exultation, and another to go as God leads, until the soul learns to humbly respond to the will of God. The shining light which opened this wonderful world fades, despite all our efforts to maintain fidelity to the Lord—and all that remains is faith. This trial can be long, sometimes interspersed with brief consolations, after which the soul can be submerged into yet greater darkness.

In some cases, this darkness may be connected with adverse external circumstances: a rift in the family, illnesses, complete failure in business, or accidents. And here the temptation arises to explain our darkness by external difficulties. We must penetrate much deeper than the sorrow of earthly existence if we want to overcome the darkness of our souls. Only this way can be revealed the darkness of the God-forsakenness of the crucified Christ, without which there would be no light of the Resurrection. Only on this path is the genuine enlightenment of the soul possible in its ability to remain with the Lord, no matter how unbearable the external circumstances, and in its capacity for compassion for all those sitting in the darkness and shadow of death.

At age seventeen Matrona lost the ability to walk: Her legs were suddenly paralyzed. She was “sedentary” until the end of her days. And her sitting—in various homes, apartments, and cellars, where she found refuge—continued for fifty years. She never grumbled about her infirmity, but meekly bore this heavy cross given her by God. When she moved to Moscow, she began roaming between family and friends. Sometimes she had to stay with people who treated her with hostility. Housing was difficult to find in Moscow, and she had no choice. She lived nearly everywhere without registration,[2] several times miraculously avoiding arrest.

We live in special times, and people are given to know special sorrows: Eternal darkness, that is, the vilest evil which covertly threatens the soul, until it is completely freed from sin in the end, is completely and openly present today in the outside world. Night is coming; “It’s later than it seems,” as they say. Millions of people are born blind. Is it their fault or their parents’ that they are born and live their whole lives in the darkness of godlessness? Today everything is done that this most terrible of blindness would be “natural” for man.

In the Gospel of the blind man, Christ does not highlight the connection between sin and suffering, between sin and blindness, as He usually does. He says that it happened that the glory of God might be manifested upon him. What are we to do, how are we to entreat God, to be the presence of Christ in the world, that the glory of God would be revealed to men? When life deals us heavy blows, we must show the world how a Christian can live and, if necessary, die.

We find this story in the life of Blessed Matrona: One day a policeman came to take Matrona, and she said to him, “Go, go quickly—there’s a tragedy at your house! I’m blind and not going anywhere. I just sit on the bed; I don’t want to go anywhere.” He listened, and went home, and found that his wife had badly burned herself on the stove, but he managed to get her to the hospital. He went to work the next day and they asked him, “Well, did you seize the blind lady?” And he answered, “I will never take her. If the blind woman hadn’t warned me, I would have lost my wife, but instead I was able to take her to the hospital.”

During the day, Matronushka would receive up to forty people. People came with their troubles, and spiritual and bodily pain. She refused no one, except those who came with evil intentions. Others saw in Matushka a “folk healer” who could remove damage or a curse, but after speaking with her they understood that before them was a godly person, and they turned to the Church, to its saving Sacraments. She helped others selflessly, taking nothing from anyone. Every day of her life brought a flood of sorrow and grief from those coming to her.

Nobody can understand, and nobody can see without light—only light heals, only love. As long as I am in the world, I am the light of the world, says Christ (Jn. 9:5), and we must be, according to His word, according to His gift, the light of the world, that others might understand. However, none of us can become light until we have passed through our own darkness, trying to overcome it, until the end, until the darkness of the cross, the darkness of all those blind throughout the ages, until the darkness of the Cross of Christ, and that means until the light of His Cross and Resurrection.

One look of Christ heals, if you can look Him in the eyes! And your brother, your neighbor—how beautiful he is, if only you could see! If only you could see and recognize Christ’s holy face in every human face!