St. Seraphim is known and venerated in Romania. There are fourteen books published about the Sarov elder in the Romanian language. Of these, thirteen are translations from Russian, English, French, and Greek. The most popular translation is the book of the Englishman Archimandrite Lazarus (Moore): St. Seraphim of Sarov: A Spiritual Biography. There is a Romanian website dedicated to St. Seraphim of Sarov where you can read recent articles about him.

Monasteries, sketes, parishes, and charitable foundations have been founded in Romania in recent times in the name of St. Seraphim—for example, the Eșanca women’s monastery near the city of Iași. There is a piece of the relics of this Russian saint in the famous men’s monastery of Sihăstria Putnei, as in other sketes and parishes.

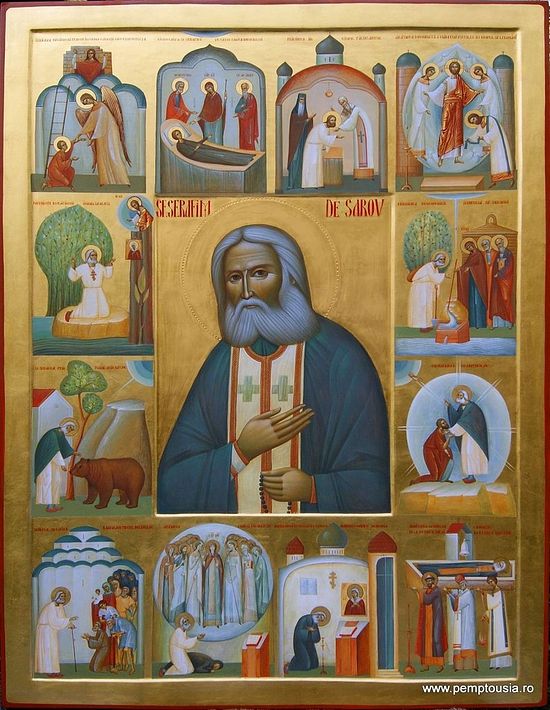

St. Seraphim was first depicted in frescoes in Bucharest’s Radu Vodă Holy Trinity Monastery under Romanian Patriarch Justinian (Marina, 1948-1977), who maintained close relations with the Moscow Patriarchate, and visited the Russian Orthodox Church several times.

In modern times, Romanian believers know the saint’s life and teachings, and some of them have testified to miracles which have happened to them.

Information on the life and teachings of St. Seraphim first came into Romanian Orthodox Church tradition not from published monographs, but from copies spread among the faithful, who read them with great delight and admiration. These typewritten texts were translations from Russian or French, secretly brought into Romania beginning in the 1950s.

Most likely, Romanian believers initially learned about St. Seraphim in Bessarabia. From 1908 to 1914, the Diocese of Chişinău and Khotinsky was headed by Hieromartyr Seraphim (Chichagov, 1856-1937). Not long before that he had made the most complete collection of materials on St. Seraphim of Sarov—The Seraphim-Diveyevo Monastery Chronicles—and actively participated in the work towards canonizing the holy elder. Vladyka Seraphim had a special devotion and veneration for St. Seraphim and often used the teachings and examples of his life in his ecclesial service among Romanians living in Bessarabia.

Political exiles fleeing from Russia to Romania also contributed to the spreading of the veneration of the ascetic. Thus, in 1930, several Russian refugees, having found shelter in Piatra Neamț, brought with them an icon of St. Seraphim painted in Russia in the nineteenth century. You can see traces from bullets from the times of atheistic persecution in Russia on it.

Later, during World War II, garrisoned in Bessarabia and Ukraine, soldiers of the Romanian army found out about St. Seraphim and brought the information to their homeland. Thus, the Romanian archimandrite Dositej (Morariu, 1913-1990) brought the book The Life of St. Seraphim of Sarov from Ukraine to Romania and translated it in 1944. Subsequently, based on this book, he wrote his undergraduate thesis, St. Seraphim of Sarov: Life, Asceticism, and Teachings, which he defended in 1947 in the Orthodox Theology Department in Sibiu (Romania). However, due to the difficult political situation in Romania, he didn’t manage to publish it. This work was published only in 2004, after the death of Archimandrite Dositej († 1990), by Romanian archimandrite and preacher Ioanichie (Balan) in the publishing house of Sihastria Monastery.

In 1943, Metropolitan Nikolai of Rostov was deported from the territory occupied by Romanian and German soldiers to Romania, along with his spiritual father, the former monk of Optina Monastery Hieromonk John (Kuligin). The founder of the periodical, “Floarea de Foc” (“Burning Bush”) and the religious movement of the same name Sandu (Tudor) and a group of his followers met Fr. John in Cernica Monastery, glorified by the works of St. Callinicus of Rimnicului (1787-1868) and the holy archimandrite Gheorghe (Ardelyanu, 1730-1806)—ascetics and restorers of the hesychast tradition in Romania in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, and contemporaries of St. Seraphim.

Fr. John became the spiritual guide for Sandu (Tudor) and the movement of intellectuals, priests, monks, and laymen gathered around him, for which the spiritual life, theology, the union of man with God, and the task of theosis became the most important things in life. The Russian monk translated their intellectual strivings into direct acts, and taught them the unceasing Jesus Prayer—prayer of the heart. He vividly testified to the Jesus Prayer by his own example, the active performance of which he learned from the Optina elders.

The Romanian elder Sofian (Bogiu, 1912-2000), who knew this Russian priest very closely, wrote in his memoirs that as a spiritual lesson he had learned much from Hieromonk John (Kuligin) about hesychasm in Russia, which could be found not only in monasteries, but even among many laymen. At meetings of the “Burning Bush” movement, it was natural to recall the life and asceticism of the saint with a fiery name—the saint who begins his spiritual directions with the word, “God is fire, warming and igniting the heart.”

(A cross procession with a particle of the relics of St. Seraphim in the church in his name in Kaminesk

(A cross procession with a particle of the relics of St. Seraphim in the church in his name in Kaminesk Later, still under the Communist authorities, information about the life and teachings of St. Seraphim was able to enter from the West, in particular through Romanian graduate students who had studied theology in European universities, mainly in France. The Russian emigration left a significant footprint there, influencing Orthodox life and theology in the West. One of these students was His Beatitude Daniel, the current patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church. His Beatitude referred to the teachings of St. Seraphim several times in his graduate thesis, which he defended in 1979 at the University of Strasbourg.

Veneration for St. Seraphim in the Romanian Orthodox Church is also expressed in poetic form. In 1957, St. John (Jacob) the New Chozebite (1913-1960) dedicated profound spiritual verses to the Russian saint: Tears on the Icon of St. Seraphim:

Venerable Seraphim, earthly angel, gazing down from Heaven upon the suffering!

Look how your people are suffering, afflicted by bloodsuckers, and how so many of your orphaned children wander.

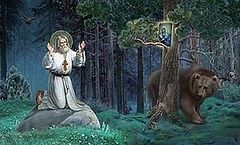

To Sarov and Diveyevo there is no path today, and darkness reigns in your vineyard, And poor orphans, like bees from a “bear,”1 are scattered throughout alien countries, and the spring2 has dried up.

Two-legged beasts have ravaged your garden, and the sick can no longer quench their thirst at your fountain. Tame “the bear,” giving him your grace; free your people from the bondage of evil.

Irrigate with holy water from the Heavenly Sarov the faith of those who are languishing in prison.

Enlighten the poor bees, removed from their hive, towards goodness, that they might know their mother.

Endow them, Batiushka, with your heavenly joy and by your fervent love warm the lonely. And grant the suffering to see the glory of Jerusalem, Venerable Seraphim.

Shepherd, strengthen those gathered, with all the hosts of the saints, to labor for the salvation of the oppressed people.

And as you were a source of peace here, on earth, so intercede now to send light to us who cry out to you.

This tradition of venerating St. Seraphim of Sarov, planted in Romania at the beginning of the preceding century, gave its fruit at the end of the twentieth and beginning of the twenty-first. After 1990, the Romanian faithful began to go on pilgrimages to Diveyevo, new translations of the life of St. Seraphim began to appear, and churches were built in his honor.

The holy Sarov elder abides in Romania; and priests, monastics, and the faithful greatly love him. The enthusiastic response of Romanian pilgrims who have visited St. Seraphim-Diveyevo Monastery and venerated St. Seraphim’s holy relics bears witness to this.

In Diveyevo you experience a state of apostolic zeal such as there was in the beginning of Christianity. There are hundreds of sisters in the monastery and its sketes—you don’t often see such monasteries today, when the attraction to monasticism has weakened. “If you desire to become a monk, become like fire,” said the great Romanian elder Hieromonk Arsenie (Boca, 1910-1989), who is often compared with St. Seraphim. Diveyevo Monastery is alive, like the Burning Bush, having inherited this fire of faith from its spiritual father, whose monastic name—Seraphim—means “fiery.” The priests serving in the monastery, the mothers at the services and at their obediences, the glittering purity of the churches, the flowers growing everywhere, the lush, eye-pleasing gardens, and especially the glorious tombs of the nuns who have departed to the Lord, continually testify to the joy of serving the Creator. And, of course, to walk the holy canal3 is remarkable. Walking this path of the Theotokos in silence, almost no one is ever in a hurry. It seems there isn’t even any time on the canal, and no need to say anything. You can understand there just how precious silence is—a virtue of which there is not enough in the bustling modern world.