The ancient city of York lies in the north of England where the Rivers Ouse and Foss join in Yorkshire. It was founded in about 71 A.D. by the Romans and called Eboracum. It became one of the principal cities of the Roman England; a military capital and a network of fine Roman roads united it with the rest of the country. Most of the earliest people in York were pagans, and there is ample evidence that they worshipped Roman and other gods here. Eboracum remained a Roman city until c. 400. A significant event happened in what is now York in July of 306: The future Constantine the Great, Equal-to-the-Apostles, was crowned here as Roman Emperor. Seven years later, in 313, St. Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, which recognized Christianity and gave freedom of worship in the Roman Empire. And later he became a committed Christian himself, and convened the First Ecumenical Council.

The first Christian communities may have appeared in York as early as the second century under the half-legendary British ruler named Lucius. But it is certain that the city had an established Christian community, priests and a bishop after the Edict of Milan. Thus, it was recorded that Bishop Eborius of Eboracum attended the Church Council of Arles in 314. Further, bishops from Eboracum most likely attended the Councils of Sardica and Ariminum in the same fourth century. However, following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, Church life in Albion began to decline and disappear, and most of what happened in York before the Augustinian mission is obscure.

St. Augustine of Canterbury, a disciple of the Pope Gregory the Dialogist and the enlightener of the English, wrote the Pope a letter in 601 asking him to send more missionaries, liturgical books and church vessels to aid him in his mission. Thus a group of new missionaries came from Rome in that year with St. Gregory’s blessing. Their names were Paulinus—the first post-Roman bishop of York—Mellitus, Justus and Rufinian. Through the labors of St. Augustine’s disciples the see of York was established in 625 and its status was elevated to an archbishopric in 735. York, which was situated in the kingdom of Deira (later Northumbria), grew into an important missionary center; that is why its Cathedral became known as a “minster”—a word used from Anglo-Saxon times for a large monastic church, usually with the status of a Cathedral.

Throughout its Orthodox period several saints served as Bishops or Archbishops of York. They are: St. Paulinus; St. Chad (who subsequently served in Mercia and became its apostle); St. Wilfrid the Elder (who served, founded churches and monasteries and preached in many parts of England, became the Apostle of Sussex in the south and even preached in Frisia); St. Bosa; St. John (who later became the founder of Beverley Monastery); St. Wilfrid the Younger in the seventh to the early eighth centuries; and St. Oswald in the second half of the tenth century, who was also Bishop of Worcester.

From 867 York was under Danish rule and renamed Jorvik, and it remained such until 954. Ancient York produced such famous scholars as the monk Alcuin (who later served at the Carolingian Court); Archbishop Egbert (who founded the famous school and library in York, corresponded with saints, and composed written works) in the eighth century; and Archbishop Wulfstan II in the tenth century. After the Norman Conquest a huge Cathedral was built in York and rebuilt between 1230 and 1472, and this Cathedral (York Minster) is the glory of the city to this day. It is the second largest Gothic church in Europe and combines several architectural styles from Early English Gothic to Perpendicular. The Archbishop of York is the senior hierarch in the Church of England after the Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Cathedral in York comprises a huge collection of stained glass and other monuments. Notably, though York is not a very big city, it has always been known as a city of churches and (outside London) it is surpassed only by Norwich for the number of ancient churches. In the Middle Ages York had no fewer than forty-five active churches, twenty of which still survive. York was also known as a monastic center: The Benedictine Monastery of St. Mary was founded here in 1088 and became very famous. It was one of the most important monasteries in the north of England. Unfortunately, it was closed under Henry VIII in 1539 and now only sections of its walls, some ruins of its church, a gatehouse and the abbot’s residence survive. Some years ago a Russian Orthodox community was set up in the city.

But let us now recall the Life of St. Paulinus of York who is venerated by Orthodox and other Christians to this day and considered by many to be one of the apostles of Northumbria.

***

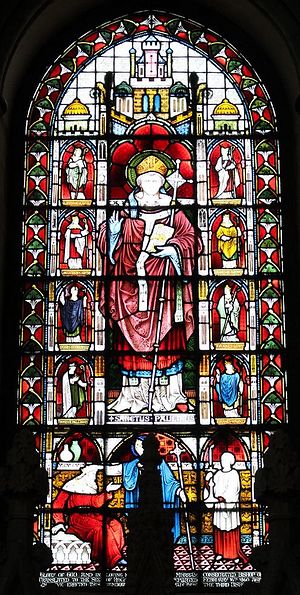

The stained glass window of St. Paulinus at Rochester Cathedral, Kent (photo kindly provided by the cathedral's Research Guild)

The stained glass window of St. Paulinus at Rochester Cathedral, Kent (photo kindly provided by the cathedral's Research Guild) In 616 St. Edwin, who still was a pagan, became King of Northumbria in the north of the country. He sent his ambassadors to Kent and asked for the holy Princess Ethelburgh, daughter of the holy King Ethelbert and the Baptizer of Kent, in marriage, to strengthen Northumbrian-Kentish ties. King Eadbald, Ethelburga’s brother, who then reigned over Kent, answered, “It is not lawful to marry a Christian virgin to a pagan husband, in case the faith and the mysteries of the Heavenly King should be profaned by her cohabiting with a king who was altogether a stranger to the worship of the True God."[2] This answer was passed to King Edwin and he promised not to act in opposition to the Christian faith that the virgin confessed; instead, he would give Ethelburgh and all who went with her full freedom to follow their faith and worship. More than that, he would embrace the Christian faith, if, being examined, it would be found more holy and worthy than paganism.

After that the virgin Ethelburgh was sent to Edwin, and Paulinus, “a man beloved of God” (according to Bede), was asked to become her personal chaplain, to instruct her and her companions and to celebrate the sacraments throughout their life in Northumbria. Paulinus agreed and soon was consecrated a bishop. It is not clear when exactly the company went to Northumbria. According to Bede, it was in 625, but, according to some historians, it may have been earlier—in about 619, and Paulinus was not consecrated immediately after their move. Anyway, Bede clearly writes that Paulinus was ordained bishop by the Archbishop Justus, on the 21st day of July, in the year of our Lord 625.

Paulinus was not only entrusted with the task of guarding Ethelburgh and her companions in faith, he was also entrusted with a mission in the north. Thus he set out zealously praying for opportunities for mission, celebrating the liturgy daily, and giving Ethelburgh spiritual advice. In fact Paulinus initially was called “Bishop of the Northumbrians”, not “Bishop of York”, and soon the mission of St. Augustine, by the blessing of God, moved forward to the north from the south. The real opportunity opened up after the conversion of St. Edwin to Christ following a chain of miraculous events. King Edwin was finally baptized, and this is how Bede beautifully describes this event: “King Edwin with all the nobility of the nation, and a large number of the common sort, received the faith, and the washing of regeneration, in the eleventh year of his reign, which is the year of the incarnation of our Lord 627, and about one hundred and eighty after the coming of the English into Britain. He was baptized at York, on the holy day of Easter, being the 12th of April, in the church of St. Peter the Apostle, which he himself had built of timber, whilst he was catechizing and instructing in order to receive baptism. In that city also he appointed the see of the bishopric of his instructor and bishop, Paulinus. But as soon as he was baptized, he took care, by the direction of the same Paulinus, to build in the same place a larger and nobler church of stone, in the midst whereof that same oratory which he had first erected should be enclosed.”[3]

Presumably some of the king’s subjects were baptized not only in York, but also in the River Derwent, which flows in Yorkshire, near the royal palace. Interestingly, a stretch of this river has been called “the English Jordan” since ancient times. In the ensuing years Paulinus also baptized other children of Sts. Edwin and Ethelburgh—namely Ethelhun, Etheidrith, and Wuscfrea. The first two died while they still were in their white baptismal robes and were buried in York. Moreover, he baptized the sons of Edwin from his first marriage—namely Osfrid and Eadfrid, along with Ifli, the son of Osfrid. Significantly, among those baptized by Paulinus were two future saints: St. Eanfled—the first daughter of Edwin and Ethelburgh (who was to become Queen of Northumbria and later Abbess of Whitby) and St. Hilda—Edwin’s grand niece (who was to found and rule the Whitby Monastery).

The following six years after Edwin’s baptism were the most fruitful and illustrious in St. Paulinus’ life, for he worked as the most zealous missionary in the whole north of England of that time. He spread the Word of God, baptized, instructed, built churches, chapels and founded holy wells in what is now the Yorkshire region, Northumbria, Cumbria, Lancashire and even further to the south, in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire. These regions corresponded to the kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia (which united into Northumbria) as well as the province of Lindsey. According to the testimony of Bede, “So great was then the fervor of the faith… and the desire of the washing of salvation among the nation of the Northumbrians, that Paulinus at a certain time coming with the king and queen the royal country-seat, which is called Adgefrin, stayed there with them thirty-six days, fully occupied in catechizing and baptizing; during which days, from morning till night, he did nothing else but instruct the people resorting from all villages and places in Christ's saving word; and when instructed, he washed them with the water of absolution in the river Glen, which is close by.”[4]Adgefrin mentioned by Bede is associated by nearly all academics with the small village of Yeavering in county Northumberland; indeed it had a palace of the kings of Northumbria from around 620 till 680, which was dug by British archeologists in the 1950s.

Here is another piece of evidence from Bede: “He [Paulinus] baptized in the river Swale, which runs by the village of Cataract; for as yet oratories, or fonts, could not be made in the early infancy of the Church in those parts. But he built a church in Campodonum, which afterwards the pagans, by whom King Edwin was slain, burnt, together with all the town. In the place of which the later kings built themselves a country-seat in the Country called Loidis [now the city of Leeds in West Yorkshire]. But the altar, being of stone, escaped the fire and is still preserved in the monastery of the most reverend abbot and priest, Thridwulf, which is in Elsiete wood.”[5] The village of Cataract mentioned by Bede is now the small town of Catterick in North Yorkshire, on the banks of the River Swale (a tributary of the River Derwent). It was here that, according to tradition, Paulinus baptized many inhabitants and was assisted by the holy Deacon James, another member of the later stage of the Augustinian mission. Campodunum was a Roman ford near Dewsbury—now a minster town in West Yorkshire where Paulinus certainly built a church, served and taught and where his memory still lives on.

There are also countless stories and traditions connecting concrete places with the missionary activities of Paulinus. Thus, he used “the pool of the Mother of God” to baptize 3,000 converts in 627, in Holystone in Northumbria, the present-day Northumberland. The holy bishop erected a church in 630 in Branxton in what is now the northern tip of Northumberland just outside the Scottish border; he is also recalled in the neighboring area of Pallinsburn (Paulinus’ stream)—a reminder of his riverside mass baptisms. The saint may have preached and erected a stone church at what is now the village West Tanfield near Ripon in North Yorkshire. Our saint baptized on the site of the present village of Easby in North Yorkshire where he has since been venerated; it is believed that he did it in the stretch of the River Swale where a monastery was later built. Paulinus certainly built the first church in Ilkley in West Yorkshire in 627, where the locals still honor his memory and where the church is one of the earliest English permanent places of worship. The tireless missionary in his journeys reached even the most remote and faraway areas of the English north, including Lancashire on the Irish Sea on the northwestern coast. It was there that he preached a sermon and maybe restored a church in Whalley in 628, where he has been permanently remembered by its residents. As St. Bede writes, King Edwin was so zealous for the worship of Truth, that he persuaded Eorpwald, king of the East Saxons [Essex], and son of Redwald, to abandon his idolatrous superstitions, and with his whole province to receive the faith and sacraments of Christ.”[6] No doubt the faith of Christ was spreading south largely due to the labors of Paulinus who worked in tandem with the holy royal couple of Northumbria.

Bede continues to inform us that Paulinus labored in Lindsey in what is now Lincolnshire in the east of England: “Paulinus also preached the Word to the province of Lindsey, which is the first on the south side of the River Humber, stretching as far as the sea [the North Sea]; and he first converted the governor of the city of Lincoln, whose name was Blecca, with his whole family. He likewise built, in that city, a stone church of beautiful workmanship; the roof of which having either fallen through age, or been thrown down by enemies, the walls are still to be seen standing, and every year some miraculous cures are wrought in that place, for the benefit of those who have faith... In that church, Archbishop Justus [of Canterbury] having departed to Christ, Paulinus consecrated Saint Honorius bishop in his stead... A certain abbot and priest of the monastery of Peartaneu [now Partney], a man of singular veracity, whose name was Deda…, told me that one of the oldest persons had informed him, that he himself had been baptized at noon-day, by Bishop Paulinus, in the presence of King Edwin, with a great number of the people, in the River Trent, near the city, which in the English tongue is called Tiovulfingacestir.”[7]

The picturesque former Roman city of Lincoln in the medieval era had as many as fifty churches, but one of them stood out as that built by St. Paulinus, who had preached and baptized in this city, assisted by St. James the Deacon. This church was called “St. Paul’s-in-the-Bail”. This church was several times rebuilt on the same place, notably in 1301, in the Georgian era and in 1877, but was demolished in 1971 and never rebuilt. Thus the city lost its unique gem and uniting link to the great bishop. A similar thing happened in our days in the city of Derby in central England when the ancient historic St. Alcmund’s Church was demolished for good. Today Lincoln is dominated by the magnificent medieval Cathedral of St. Mary the Virgin, the third largest cathedral of England, which is, however, not connected with our saint. Tiovulfingacestir, mentioned by Bede, which means “the fort of the descendants of Tiovulf”, is now the village Littleborough in Nottinghamshire. This settlement was originally Roman and had a long history, and Paulinus well may have baptized hundreds of converts in the deep waters of the river. We should note that it was a part of Mercia, not Northumbria at that time, so fruitful were the apostolic endeavors of Paulinus. Local traditions link Paulinus to the places of East Stoke and Southwell in the same county of Nottinghamshire where he reputedly performed mass baptisms. Amazingly, the baptismal pool of Southwell (which was used for many centuries afterwards) gave its name to the whole town, and a cathedral, known as Southwell Minster, was later built on the site of this very pool. The faithful Deacon James aided Paulinus at both Littleborough and Southwell.

A tragic event happened on October 12, 633. On that day the holy King Edwin was slain in a battle at Hatfield Chase by the joint army of the Welsh King Cadwallon, a Christian in name only, and King Penda of Mercia, “a most warlike man of the royal race of the Mercians”, as Bede characterized him. Edwin was venerated as a martyr after that and his head relic rested in York. But that day marked the end of the missionary efforts of Paulinus in the north. A strong pagan reaction began in Northumbria, and as the nation was still newly-baptized and not fully converted, the situation quickly changed for the worse. Thus Paulinus had to leave Northumbria. He took the widowed queen Ethelburgh and her daughter Eanfled, and returned to Kent by sea. In Canterbury the saint of God was most honorably received by St. Honorius, mentioned before, and King Eadbald. Notably, Pope Honorius of Rome did not know that Edwin had been killed in 633, so he sent St. Paulinus the pallium as to the Archbishop of York in the year 634, but he never used it. According to Bede’s account, Paulinus brought with him “many rich goods of King Edwin, among which were a large gold cross, and a golden chalice, dedicated to the use of the altar”[8], which still were shown in the church of Canterbury at the time of Bede.

By the year 633 Bishop Romanus of Rochester in Kent, the second English diocese founded in 604, was dead. So St. Paulinus, who was then about sixty, headed this see as it was vacant. The holy man ruled the Diocese of Rochester for the remaining eleven years of his life. We know very little of his activities there, but it is certain that he helped St. Ethelburgh, who founded the convent of the Virgin Mary in Lyminge in Kent, arrange the life of her convent. He may have also made a trip to Glastonbury to Somerset in the kingdom of Wessex where helped rebuild the church. In the memory of Paulinus’ episcopate in Kent two ancient parish churches still bear his name, though today administratively they are located in London. These are St. Paulinus’ Church in Crayford and St. Paulinus’ Church in St. Paul’s Cray (the latter is no more used for Anglican worship, although it is 1,000 years old).

The saint of God reposed on October 10, 644, and was buried in Rochester Cathedral, having served the English Church for forty-three years. His feast-day has been observed on that day (according to the old calendar) since then. With time the veneration of Paulinus became national; he was particularly venerated in the north, in major English monasteries, York, Rochester and Canterbury. No fewer than five early churches were dedicated to him. Several years ago a long-distance walk, St. Paulinus Pilgrimage and Heritage Way, which begins from Todmorden on the Lancashire/Yorkshire border and ends in York, was started. Let us now say a few words about the places where our saint is commemorated today.

Rochester is a port town near London in Kent, standing on the River Medway estuary. It is famous for its ancient cathedral and castle which stand in front of one another. In the Orthodox period it was blessed by having three saintly bishops, all of whom lived in the seventh century: St. Justus (buried in Canterbury), Paulinus and Ithamar. The relics of the latter two were laid and venerated inside this Cathedral after their death. Following the Norman Conquest the building of a new Cathedral was undertaken by Bishop Gundulf in 1080, and it was then that the relics of St. Paulinus (and later Ithamar) were translated to it and laid in a silver shrine. They were displayed by the high altar and visited by numerous pilgrims until the Reformation, when they were most probably destroyed. Gundulf also established a community of Benedictine monks at the Cathedral; in fact England is famous for its ancient “monastery-cathedrals”. The nave, the west front, the western part of the crypt and the tower on the north side of the present Cathedral date back to Gundulf’s period.

The Orthodox fresco of baptism at Rochester Cathedral (source - Stephen Craven from Geograph.org.uk)

The Orthodox fresco of baptism at Rochester Cathedral (source - Stephen Craven from Geograph.org.uk) From the monastic past one can see remains of the cloister and the chapter house which date from the twelfth century. Among numerous interesting monuments within this cathedral let us mention a splendid fresco created in recent years by the Russian Orthodox painter Sergey Fyodorov. It decorates a wall of the north-west transept and depicts the Baptism of the Lord at the top, and the baptism of Kent below: on the bottom left, St. Augustine baptizes King Ethelbert in a font, and on the bottom right Ethelbert’s subjects are baptized in the River Medway which is followed by their first communion from the hands of St. Justus, the Cathedral’s founder. The Cathedral also has a stone statue of St. Paulinus along with statues of other saintly figures on the quire screen (also called the pulpitum screen and organ screen). One of the Cathedral’s numerous stained glass windows (as in York Minster and elsewhere) commemorates St. Paulinus—it can be found in the north quire transept between those of Bishops Gundulf and Walter de Merton. The edifice’s official name is the Cathedral Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary, the original cathedral being dedicated to the Apostle Andrew.

Statues from left to right of Sts. Ethelbert, Justus and Paulinus at Rochester Cathedral (photo kindly provided by the cathedral's Research Guild)

Statues from left to right of Sts. Ethelbert, Justus and Paulinus at Rochester Cathedral (photo kindly provided by the cathedral's Research Guild)

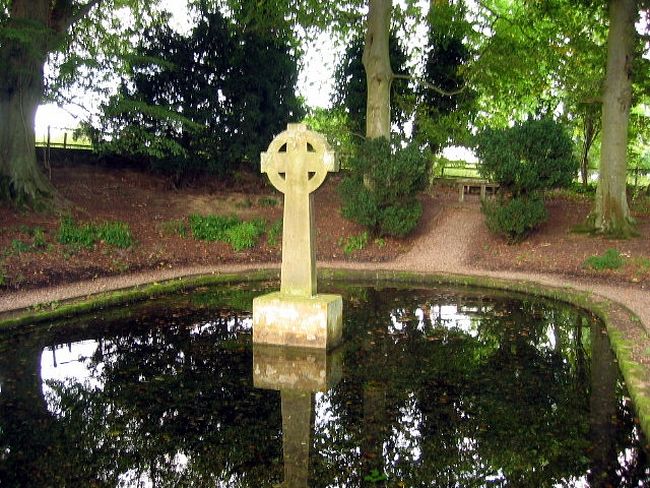

The hamlet of Holystone in Northumberland, on the bank of the River Coquet, still has a large and ancient baptismal pool which may date as far back as the Roman era. According to ancient traditions, this well was used by St. Ninian in about 400, then blessed by St. Paulinus during his missionary journeys in the 620s. There is a Celtic-style nineteenth-century cross in the middle with an inscription mentioning Paulinus; the saint’s statue stands at one corner of the pool. Its official name is “the Lady Well” because a small community of Augustinian nuns settled here in the twelfth century and chose the Mother of God as their Protectress. The local parish church was originally the monastic church, though it was since rebuilt. The village remarkably has another holy well, dedicated to St. Mungo (Kentigern), the founder of Glasgow, who is believed to have performed baptisms and preached here as well. This well is tiny in comparison with the Lady Pool. The village of Branxton in the same county has a church dedicated to St. Paul, originally to St. Paulinus, which was rebuilt in the 1840s, while retaining some early medieval features. It was certainly built by Paulinus during one of his missionary trips.

The village of Easby in North Yorkshire preserves the ruins of a medieval Premonstratensian abbey that once housed a relic of the Holy Martyr Agatha of Sicily along with a little but active parish church of St. Agatha, built at the beginning of the twelfth century. The church houses a replica of the exquisite Saxon preaching cross whose fragments were incidentally discovered built into a church wall in the last century. Now the original is kept at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The surviving sections depict Christ in Majesty, the apostles and other scenes. Paulinus baptized the Northumbrians in the river behind the church and perhaps built a church here, though the present structure is Norman and later. The church cross may be somehow connected with Paulinus or even created in honor of him. The church also preserves a set of exceptional rare thirteenth-century wall-paintings depicting Adam and Eve, the Fall of Man, the Nativity, the Annunciation, the Deposition of Christ from the Cross and the Women by Christ’s empty tomb.

The Yorkshire spa town of Ilkley, on the south bank of the River Wharfe, still preserves the All Saints’ Church, originally built by Paulinus in the seventh century. The church boasts three Saxon stone crosses which are already 1200 years old. The crosses are miraculously well-preserved and they are now inside the building to prevent erosion; one of them depicts the Savior in majesty on one side and the four Evangelists on the other side. Parts of the church date from the thirteenth century, but nevertheless its early spirit is still very much alive. Two carvings on either side of the church porch represent Sts. Paulinus and Edwin.

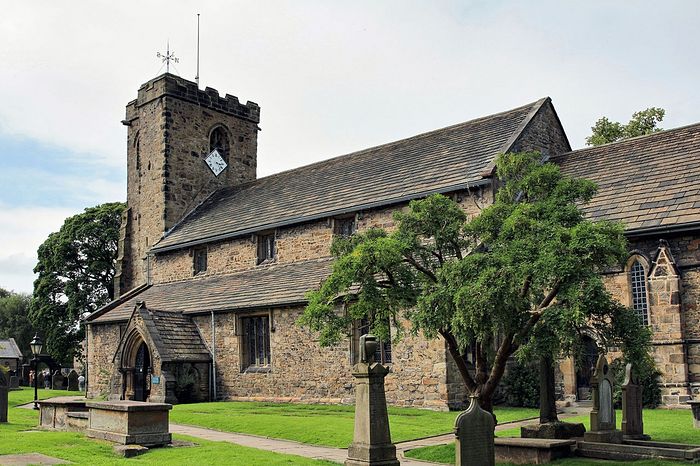

The small town of Dewsbury by the River Calder in Yorkshire has a church which was originally wooden and built by Paulinus who preached here, but by modern times has grown into an enormous edifice. It was a significant missionary center in the late-Saxon period, hence its name “Minster”. Dewsbury Minster retains some Saxon stone fabric, particularly in the nave, although it has many later additions up to the Victorian era. Inside it has a heritage center displaying many priceless artefacts: notably parts of the huge Saxon cross created in the memory of St. Paulinus in the ninth century, with the inscription: “Here Paulinus preached and celebrated” in Latin. There is also a modern model of how this cross might have looked there. The minster itself is dedicated to All Saints, and it has a purposefully-built chapel in honor of St. Paulinus which displays an early cross (most probably a part of the mentioned Paulinus Cross) depicting Christ in Majesty. The Reredos, a large wooden screen carved with images of Saints (especially the northern English saints) and Christ with the twelve apostles, was built in 1913 and installed behind the altar. The church’s stained glass is mainly of the fourteenth century with some modern masterpieces. A plaque on the south aisle wall commemorates Revd. Patrick Bronte (1777-1861), the father of the three talented Bronte sisters, world-renowned authors of very deep literary works. He was an Irishman and began his ministry at the Dewsbury church in 1809 where he served till 1811. He ended up at Haworth (the home of Charlotte, Anne and Emily) where he served as a priest for forty-one years from 1820 till 1861. This church was in the last century in competition with the church at Wakefield as the center of a new diocese, but in the end Wakefield, not Dewsbury, became the new cathedral. Numerous Anglo-Saxon graves were recently discovered locally.

A cross fragment depicting Christ in Majesty at Dewsbury Minster (photo provided by the vicar of Dewsbury Minster)

A cross fragment depicting Christ in Majesty at Dewsbury Minster (photo provided by the vicar of Dewsbury Minster)

York Minster, dedicated to the Apostle Peter and situated in the city of York, has numerous monuments commemorating St. Paulinus. These include “the Chair of St. Paulinus” dating to about 1550 which has lately been partially restored and is now located in St. Michael’s Chapel; a cupboard used as a font cover in the crypt with depictions of Sts. Ethelburgh, Edwin, Paulinus, Hilda and James the Deacon inside; a red brocade frontal at St. Nicholas Chapel with an embroidery of nine saints, including Paulinus; the Great East Window in the center of east wall of the Lady Chapel with images of Sts. Gregory, Paulinus and Wilfrid; the Wolveden Window (the third window from the west in the north wall of the north quire aisle) depicting Paulinus as preaching at King Edwin’s court, the enthronement of Paulinus of Bishop of York and Paulinus under a canopy; St. Cuthbert’s window (in the south wall of the south transept of the quire) depicting on the bottom panels Sts. Paulinus, James the Deacon, Edwin and Etheldreda; an early fifteenth-century clerestory window in the north wall of the quire; the St. Paulinus oil image on canvas (in the storeroom) portraying the saint in red robes and fur trim and with a crozier in the left hand. (The information on these monuments was kindly provided by the York Minster Collection team).

The village of Whalley in Lancashire, on the banks of the River Calder, was blessed to have one of the earliest churches in England. The church built or restored by Paulinus was later replaced by the current structure, it is now dedicated to St. Mary and All Saints. There are three late Saxon crosses in its churchyard and many misericords of various epochs inside the building. A Cistercian monastery eventually appeared in Whalley near the church in 1296 as the monks sensed the holiness of the spot, blessed by the prayers of Paulinus. The monastery is already long gone—it was closed in 1538 and the abbot executed for “high treason”, but its ruins survive and are looked after by Anglicans.

The picturesque village of Littleborough in Nottinghamshire is 2000 years old. Its stream where Paulinus baptized hundreds in the king’s presence is still very much alive today. There is a church dedicated to St. Nicholas very close to the stream. The church is tiny and is not used for regular worship nowadays; its fabric is either late Saxon or early Norman. According to one version, it was built by William the Conqueror and has largely been restored in the past two centuries. There are Saxon pillars in its sanctuary.

The small town of Southwell in the same county has a medieval Cathedral, which is less visited by pilgrims than the more famous great English cathedrals. However its atmosphere is one of holiness and antiquity. According to one version, Paulinus performed mass baptisms on this spot, and baptisms were continued for centuries after him. The Cathedral, known as Southwell Minster, was built over this pool which is now buried under its floor. Another tradition claims that the Cathedral was built on the site of the church built by Paulinus—this legend is depicted on the baptistery window here. The Cathedral dates back to the mid-tenth century when a college of prebends was established here. Its most celebrated artefact is the Saxon carving of Archangel Michael in the north transept; the composition is called the Tympanum. The Cathedral has the only octagonal chapter house in England, and its columns are richly adorned with carvings of foliage, flowers and human figures of perfect craftsmanship; a splendid Perpendicular west window of an angel; an elaborate carved pulpitum (or choir screen) with carvings of flora, strange faces and other peculiarities; and boasts a thirteenth-century Pilgrims’ chapel, among other things. The Cathedral was founded by an archbishop of York and one of its chapels is dedicated to St. Oswald of Worcester who was also Archbishop of York. The area around the town is rich in other holy wells, but these are not associated with Paulinus.

We see that though Paulinus preached and baptized in Northumbria very energetically and successfully, he was not able to organize a full-fledged diocese and church life in the north, most probably due to the shortage of time, as his mission came to an abrupt end by St. Edwin’s martyrdom. His and Edwin’s labors, however, were continued and finished in the north by another bishop and another king—Sts. Aidan of Lindisfarne and Oswald of Northumbria. Nevertheless Paulinus laid a solid foundation on which the future mission was completed, and spiritual life flourished in the north after him. Today dozens of places, mentioned and not mentioned in this article, bear testimony to his self-sacrificing labors for the Glory of God.

Holy Hierarch Paulinus of York, pray to God for us!