This essay was written in the early twentieth century by the excellent Russian Orthodox theologian, exegetist and liturgical scholar Michael Nikolaevich Skaballanovich (1871-1931), son of the great Russian byzantinist and Church historian Prof. Nicholas Afanasyevich Skaballanovich (1848-1918). Master of Theology, Doctor of Church History and teacher at the Kiev Theological Academy for twelve years, M. Skaballanovich was eventually repressed by the Soviet Government and died in exile in Arkhangelsk at the age of sixty. One of his most famous works is The Explanatory Typicon.

The city of Bethlehem—the native town of King David and the birthplace of his glorious Descendant, Christ the Savior—sits on an elevation (2,542 feet above sea level) formed by two elongated hills, the eastern and western ones, united by a short ridge. There are valleys just to the north and the south of Bethlehem and gentle slopes just to the east and to the west. It takes roughly two hours to get from Jerusalem to Bethlehem (which lies to the south of it) on foot. The surroundings of Bethlehem are very attractive and preserve a feeling of coziness and joy.

The hills of Bethlehem are covered with ample vegetation and gardens with many species of trees—olive trees, grapevines, fig trees and others. The surrounding hills and valleys are covered with green gardens as well. As one traveler said, admiring the picturesque views in the vicinity of Bethlehem you cannot help but recall all the Biblical events that once happened here.

A small square building with a dome can be seen in the distance: This is the tomb of Rachel—the beautiful wife of the Hebrew Patriarch Jacob of the Old Testament whom he loved dearly; it is here that she passed away, was mourned and buried by him on the way to Bethlehem (see Gen. 35:16 and 48:7). And here are the ruins of Ramah [now al-Ram—trans.] mentioned by the prophet who foresaw the Massacre of the Holy Innocents: A voice was heard in Ramah1, lamentation, and bitter weeping; Rachel weeping for her children refused to be comforted for her children, because they were not (Jer. 31:15). And here are the fields where the poor Ruth gathered the grain left behind by the reapers in order to feed her aged mother-in-law whom she loved as her own mother. The Lord rewarded Ruth for her good deeds and she became the wife of a wealthy and influential Bethlehem citizen named Boaz, and is ranked among the foremothers of the Savior of the world. And there below, in the valleys of Bethlehem and on the neighboring hills with fruitful trees and abundant sweet springs, the young David—the noble great-grandson of Ruth—would tend his father’s flocks; it was there that he killed a lion and a bear, protecting his sheep, and played his wondrous psalms with his harp. It was amid the same mountains that he afterwards more than once hid from Saul when the latter was pursuing him everywhere, as if he were a runaway slave or a villain. And you cannot help but recollect the moving, pleading words of the meek youth, addressed to the vicious persecutor: Wherefore doth my lord thus pursue after his servant? What have I done? or what evil is in mine hand? (1 Sam. 26:18). And it was here, in Bethlehem, that Prophet Samuel found David and anointed him to be king, and later, when David became King of Israel, Bethlehem was given the honorary title of the City of David. Here, on the fields of Bethlehem, we also see King David’s well: at the time when Bethlehem was occupied by Philistines he once got extremely thirsty and asked someone to bring him water from that well to drink. And the three mighty men brake through the host of the Philistines, and drew water out of the well of Bethlehem, that was by the gate, and took it, and brought it to David: nevertheless he would not drink thereof, but poured it out unto the Lord. And he said, Be it far from me, O Lord, that I should do this: is not this the blood of the men that went in jeopardy of their lives? (2 Sam. 23:16, 17). David proceeded to utterly defeat the enemies and recapture the city. Further beyond the hills are the famous Solomon’s pools from which this wise king built his water aqueduct that reached Jerusalem—a structure that amazes many to this day2.

These are the Biblical events that recur to the memory of every Christian at the sight of Bethlehem and its surroundings. But these recollections are weak and dim compared with those of the greatest event, which illumined the human race with a new light, and gave Bethlehem its true glory and greatness—the Birth of Christ! All of Bethlehem’s subsequent history was marked by its significance as the birthplace of Christ, the Savior of the world, as a place of Christian reverence and pilgrimage. As early as the first centuries of Christianity, Bethlehem developed thanks to the pilgrimages of pious Christians to this holy site. The Holy Emperor Constantine the Great built a splendid basilica in Bethlehem in the first half of the fourth century, and later St. Justinian renovated it. Afterwards monasteries and churches were built here, so that by 600 A.D. the city prospered and was known throughout Christendom.

However, as was the case with most other greatly revered shrines of the Holy Land, the destructive blows of history did not spare Bethlehem. In the twelfth century Arabs destroyed Bethlehem almost entirely, when they saw the approaching crusaders who, in their turn, restored it later. In 1244, the city was ravaged by people from Khoresm [a historical region and former small kingdom in Central Asia], and in 1489 it was almost wiped out. It was only in the past centuries that Bethlehem was gradually restored and became largely a Christian town. In 1831, Muslims were banished from the city following their revolt because of new taxes, and in 1834 by orders of Ibrahim Pasha the whole neighborhood where they had lived was destroyed after another uprising.

Today there are about 11,000 residents in Bethlehem, and nearly all of them are Christians.3 Their main occupations are agriculture and cattle-breeding; in addition, for the past few centuries they have been engaged in making small items for pilgrims and have been particularly skillful in creating ornaments of mother-of-pearl: small crosses, representations of Biblical scenes and so on. These are also made of coral and a special stone called “stinkstone” (a compound of resin and mineral pitch, produced in the Dead Sea)4.

The entire small city, divided into eight quarters, is adorned with buildings and structures of various Christian denominations. As for Roman Catholics, here they have a large Franciscan monastery with a hospice, a beautiful new church on a slope of the hill behind the former large church, a school for boys with a school for girls (Sisters of St. Joseph), an orphanage, and a pharmacy. In the city’s south-east you can find the Convent of Carmelite Sisters, modelled after the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome, complete with a church and a seminary. There is the Hospital of the Sisters of Mercy in Hebron Street in the north-east. The Armenian community also has a large monastery in Bethlehem, adjoining the Greek and the Franciscan monasteries—in the aggregate all of them form one massive fortress-like structure in the city’s southeastern corner. There are few Protestants in the city (up to sixty in number).

But the principal and most important Christian shrine of the city is the Church of the Nativity of Christ together with the cave (or grotto), situated on the edge of the city on the eastern hill, close to a steep slope down to the valley. The Church of the Nativity of Christ is remarkable not only because it is built over the site where the Savior of the world was born, but also for the antiquity of its major features. It is known that Constantine the Great erected a basilica over the cave where according to tradition Christ had been born. We can presume that the present edifice in its general appearance is largely the same ancient basilica, albeit partially transformed and altered by time and history. In any case, this supposition is supported by the unity of the general style of the present building and the absence of the characteristics of modern times. If we assume that the Church of the Nativity was considerably restored by Justinian (527-565), then even in this case the temple is a fine example of ancient Christian art.

True, in the subsequent centuries the church was remodeled and altered, but not to a great extent. Thus, in the twelfth century the church walls were decorated with mosaic on a gold background by orders of the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Comnenos (1148-1180); the church itself was then covered in tin. In the fifteenth century (1482) the roof fell into disrepair and required repair work that was carried out with the help of the rulers of Western countries (Kings Edward IV of England and Philip of Burgundy). In the late seventeenth century, Turks removed lead from the church roof and melted it down for bullets, while most of the mosaic of Manuel Comnenos had crumbled even earlier.

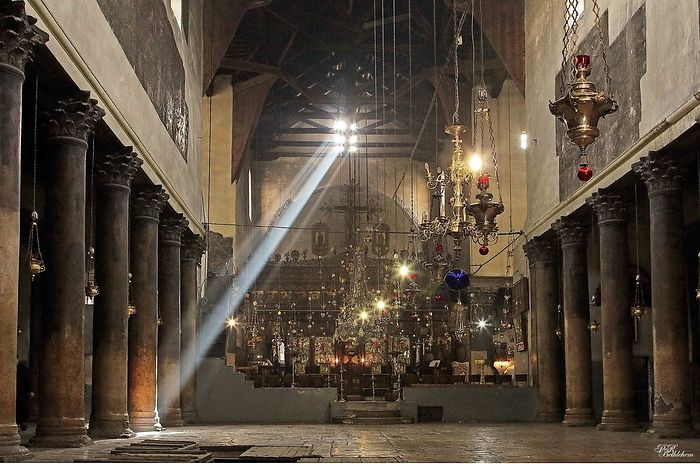

The Church of the Nativity of Christ stands in front of a larege paved square; traces of the original court (atrium) of the ancient basilica can still be discovered in front of the main entrance to the church from the west. Of the three doors that originally led to the church porch, only the central one survives—it forms the current main entrance; but it has been blocked for ages too, and only a very low door was left as the main entry. The church porch, which is as wide as the temple’s central nave, is dark and divided into several parts by walls. Formerly three doors led inside the church from the porch, but two of them are now blocked, and only the central one remains. The church interior wins admiration for its grand simplicity. It has the shape of a grand hall, partitioned by four rows of columns of solid red marble with white streaks (with eleven columns in each row; each column is about 19.6 feet high) into five naves; the central nave is twice as wide (c. 34.12 feet) as all of the side naves on either side; the side naves are lower than the central one. The church columns are quite beautiful and original: their pedestals rest upon a tetragonal slab; their capitals look Corinthian yet their style was slightly altered; above they have deeply-carved small crosses. Here and there on the church walls you can see remnants of the mosaics of Emperor Michael Komnenos; besides, there are seven depictions of the nearest ancestors of St. Joseph (half-lengths), the most important Ecumenical and Local Councils, above—a series of foliation, images of angels on the ceiling and so on. A dead wall separates this part of the church from the third part, which incorporates the actual Church above the Grotto of the Nativity of Christ. Three doors lead to this part of the temple. It is actually the extension of the central nave intersected by the transept. Both these naves taken together are in the form of a Latin cross; there are four piers in their four crossing angles. The apse of the main central nave contains a Greek chancel and an altar, separated from the western part of the church by a small ambo and an iconostasis. Remains of mosaics on the walls of this part of the temple depict various scenes from the life of Christ: the south apse has quite an unusual depiction of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem; the north apse has a depiction of the apparition of the Risen Christ to St. Thomas and other apostles; the apostles are shown without halos; the third depiction is that of the Ascension of Christ, and the apostles are without halos here either; the Mother of God is amidst the apostles; the top of the painting is missing.

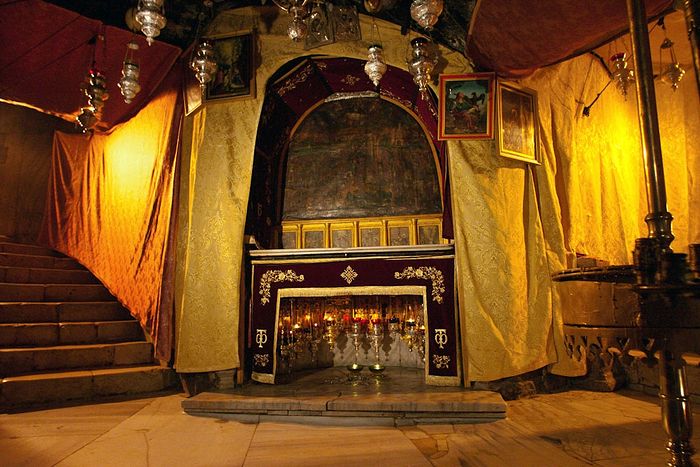

Two staircases lead down to the Cave (Grotto) of the Nativity of Christ from this part of the church. They are situated on the right and the left sides of the solea of the Orthodox sanctuary; now the right (south) one belongs to the Orthodox community, whereas the left (north) one belongs to the Catholic community. The Grotto of the Nativity of Christ, located beneath the Orthodox altar, is rectangular: it is about 40.68 feet long, about 12.8 feet wide, and about 9.84 feet high. The whole cave is illuminated by means of thirty-two icon lamps, its floor and walls are covered with slabs of marble. The eastern niche has an altar with a silver star above it bearing the Latin inscription which reads, Нiс de Virgine Maria Iesus Christus natus est (meaning “Here Jesus Christ was born to the Virgin Mary”). One cannot read these words without awe and spiritual delight, as they say so much to our minds and hearts! Fifteen icon lamps burn around this niche of which six belong to Greeks, five belong to Armenians, and four to Catholics. However brightly these icon lamps may burn, their light is dim and faint compared with the radiant everlasting Light, the Light of the world, which began to shine here!

Down three steps opposite the grotto, is the Chapel of the Manger, situated in a separate cave. The manger itself is of marble: the bottom is of white marble and the side walls are of brown marble; a wax figure of the Infant Christ lies in the manger. Therein in the west is the Latin Altar of the Adoration of the Magi with a (contemporary) depiction of this event. Beside this cave the stairs lead to the south parts of the grotto from the south-west corner of the St. Catherine’s Church: first to the Chapel of the Holy Innocents, where, according to a later fifteenth-century tradition, Herod ordered the murder of several infants hidden here by their mothers. Five steps up lead to the St. Joseph’s Chapel erected in 1621 on the supposed site where an angel had ordered him to flee to Egypt with the Infant Jesus. Apart from all this, the following relics in small separate caves are highly venerated by Christians, especially by Roman Catholics here: the tomb of Blessed Jerome of Stridon (c. 341-420; feast: September 30); the tomb and the altar of Presbyter Eusebius of Cremona; the tombs of the disciples of St. Jerome—namely Sts. Paula and her daughter Eustochium; and, lastly, the cell where the Blessed Jerome spent thirty-six peaceful years of his life, translating most of the Holy Scriptures into Latin (the work became known as the Vulgate) and writing other works for the good of the Church. There is also the Milk Grotto, where, as Roman Catholics believe, drops of the Virgin Mary’s breast milk spilled to the ground while She was nursing the Baby Jesus; also there are the Valley of Shepherds and the “Shepherds’ Settlement” of Beit Sahour—the shepherds who were the first to hear the Good News of the Birth of the Savior from the angelic hosts were believed to hail from that place5.

Everything in this holy place is imbued with the spirit of the great event—the Birth of Christ; everything here inspires each Christian to lift his mind upwards to the Divine Infant and bend his knees before the glory of the inexhaustible mercy of the Son of God!