The Baptism of the Lord: Icons and Frescoes

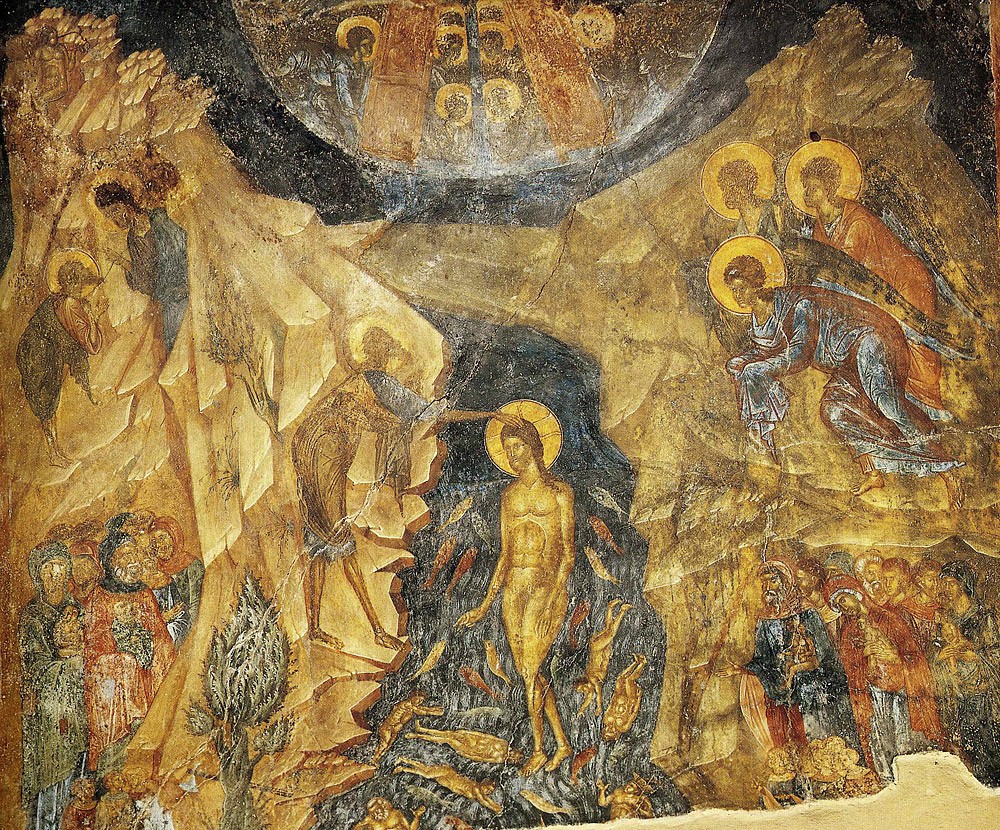

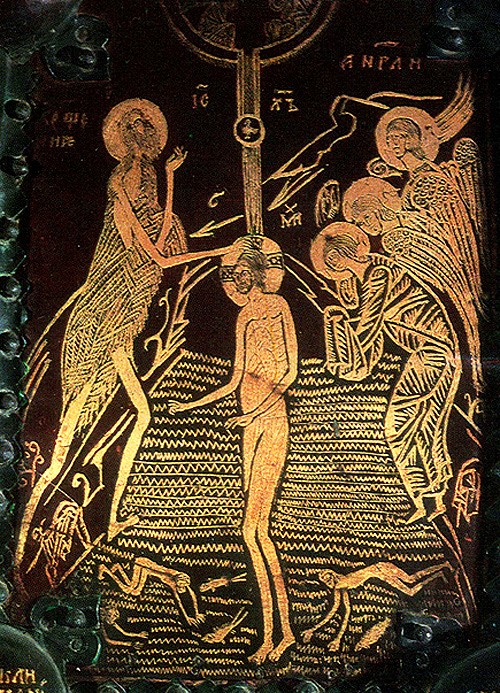

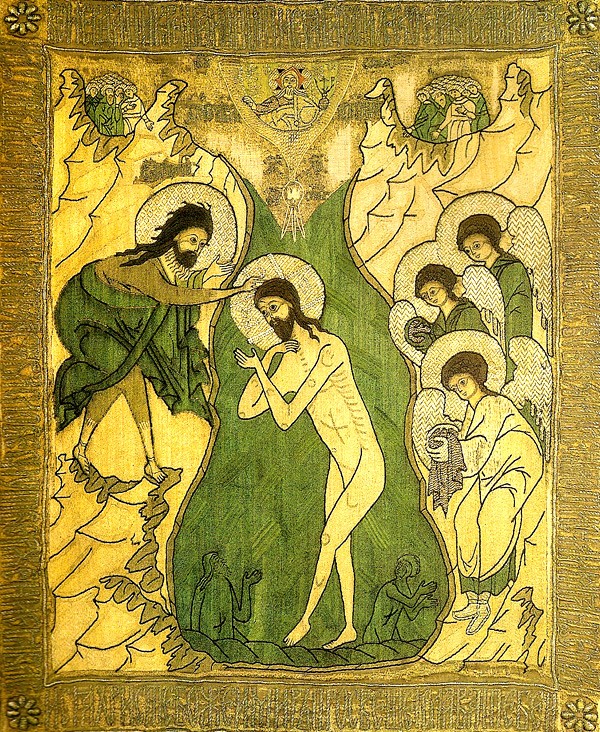

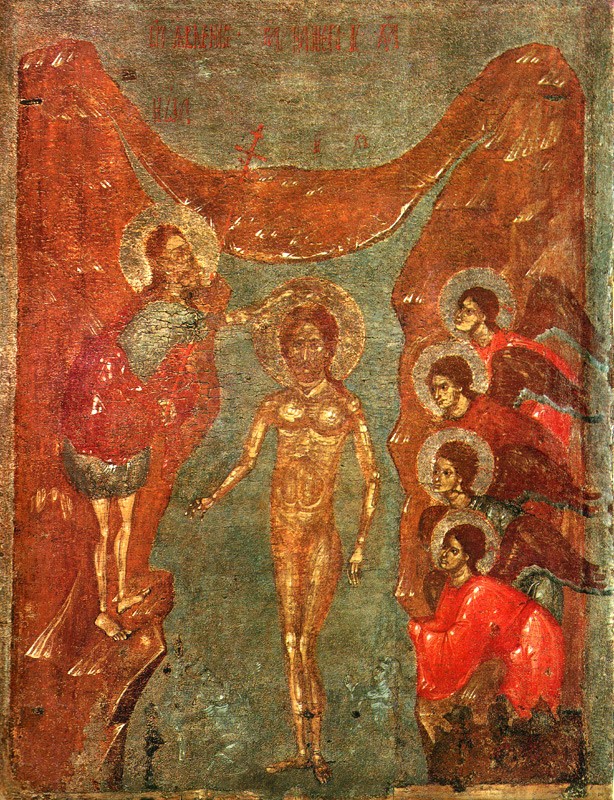

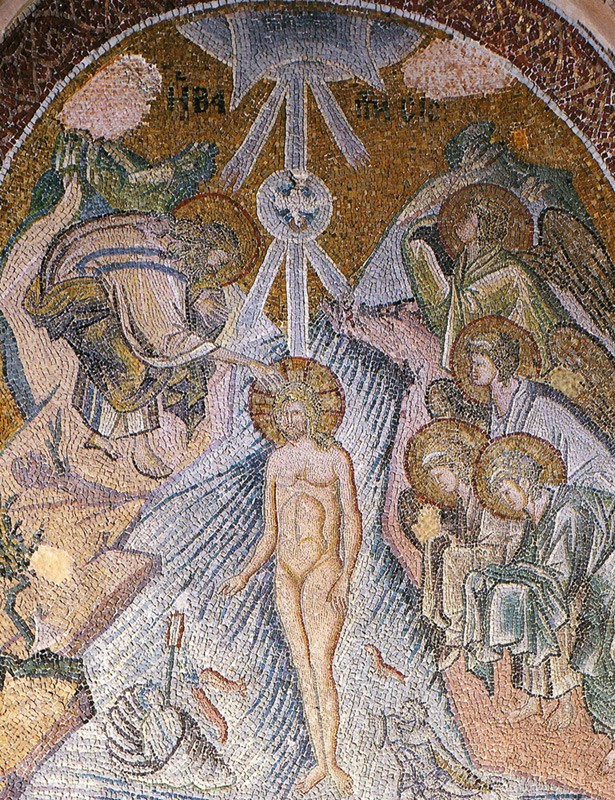

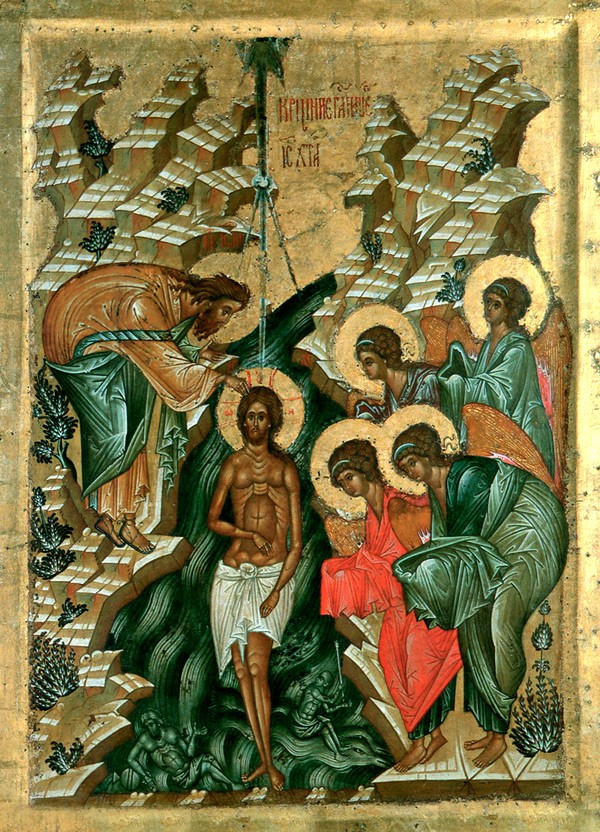

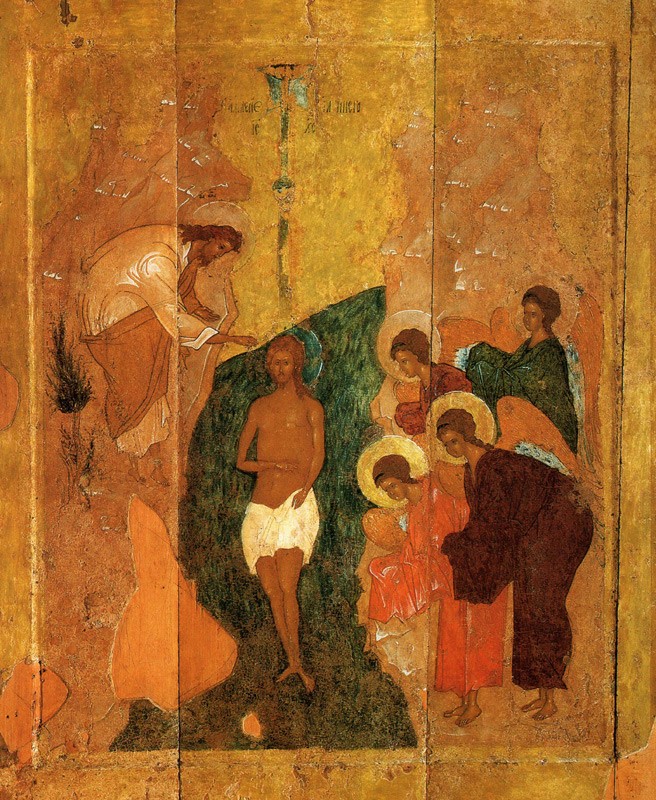

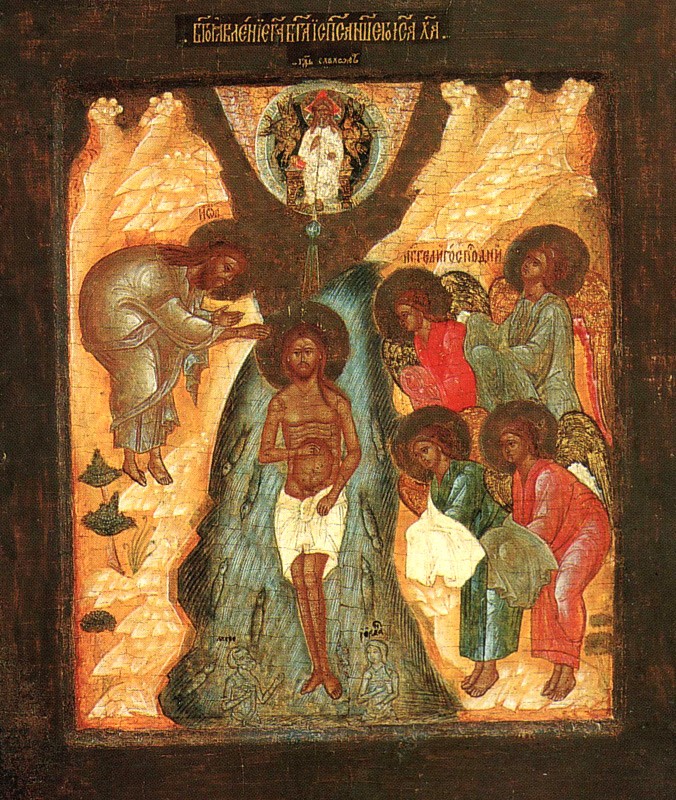

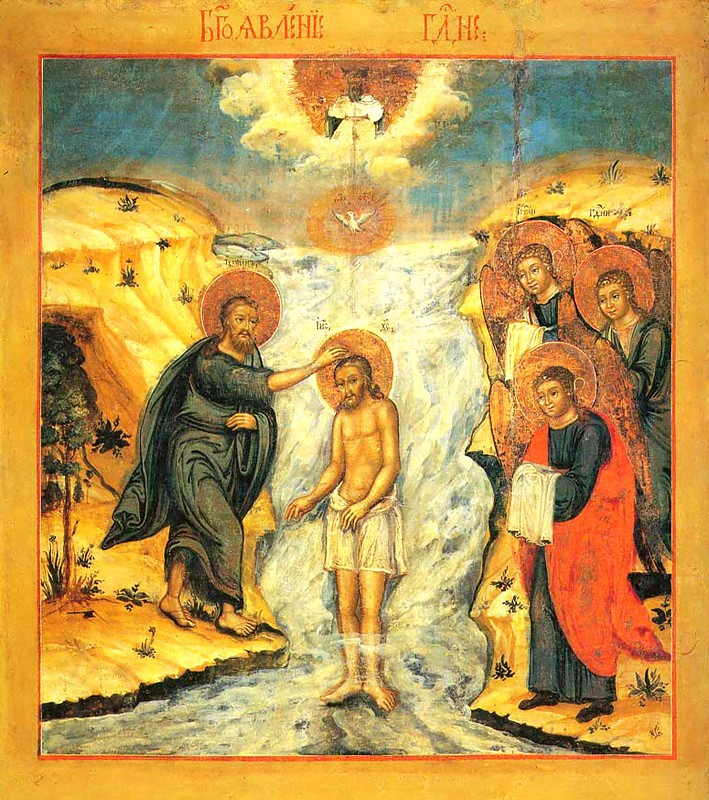

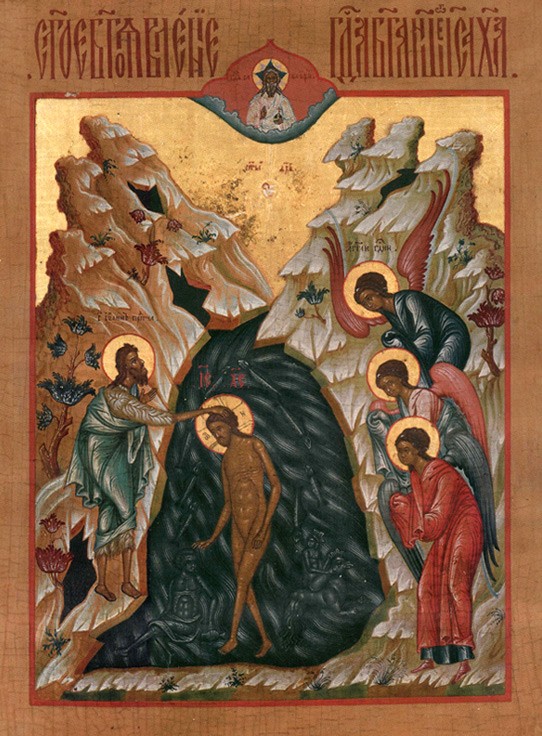

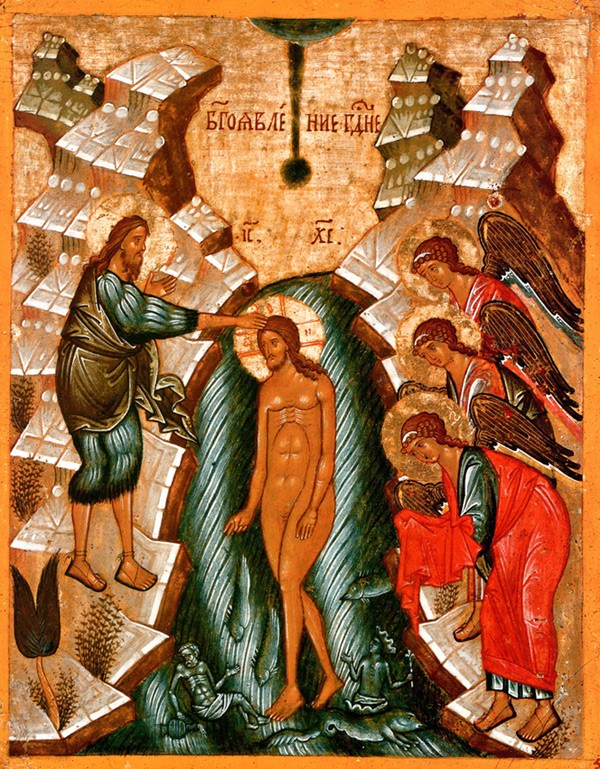

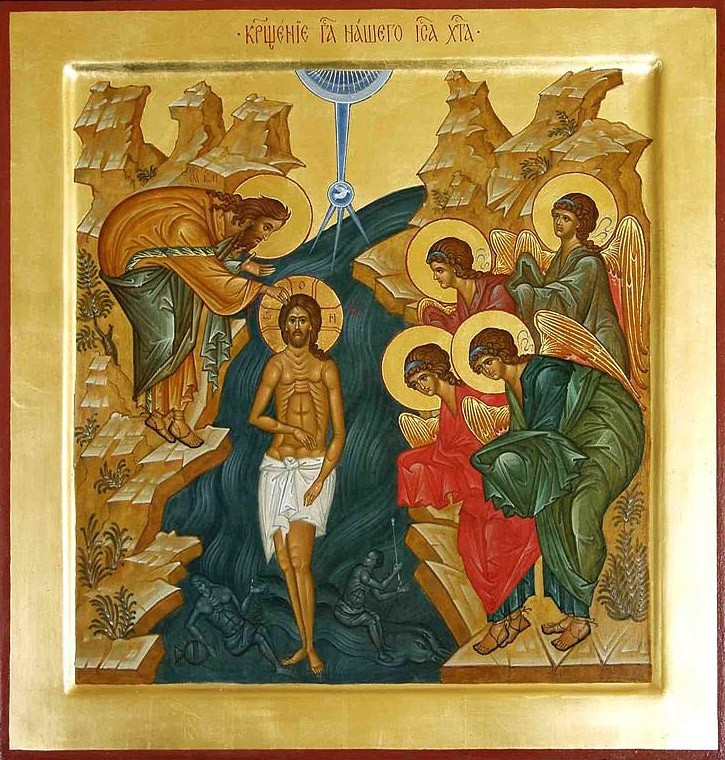

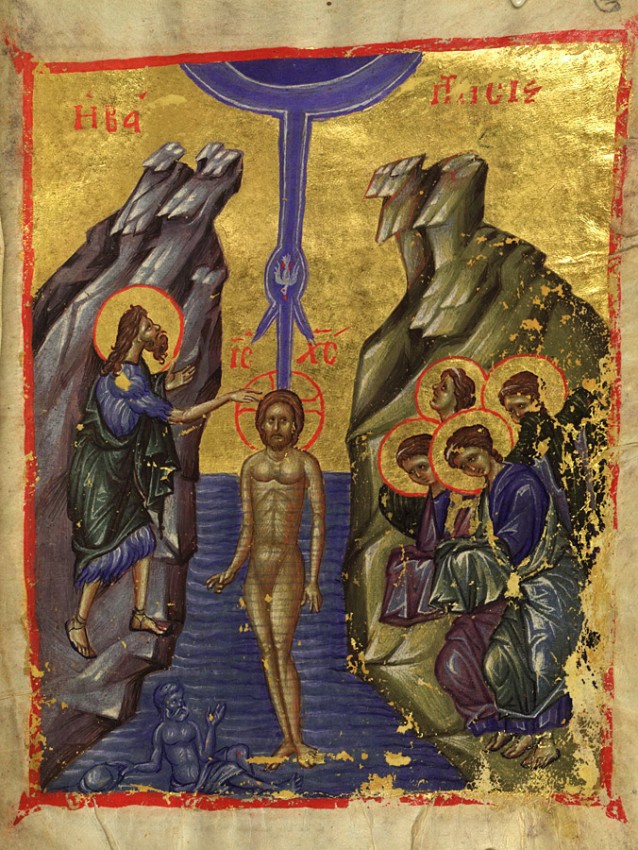

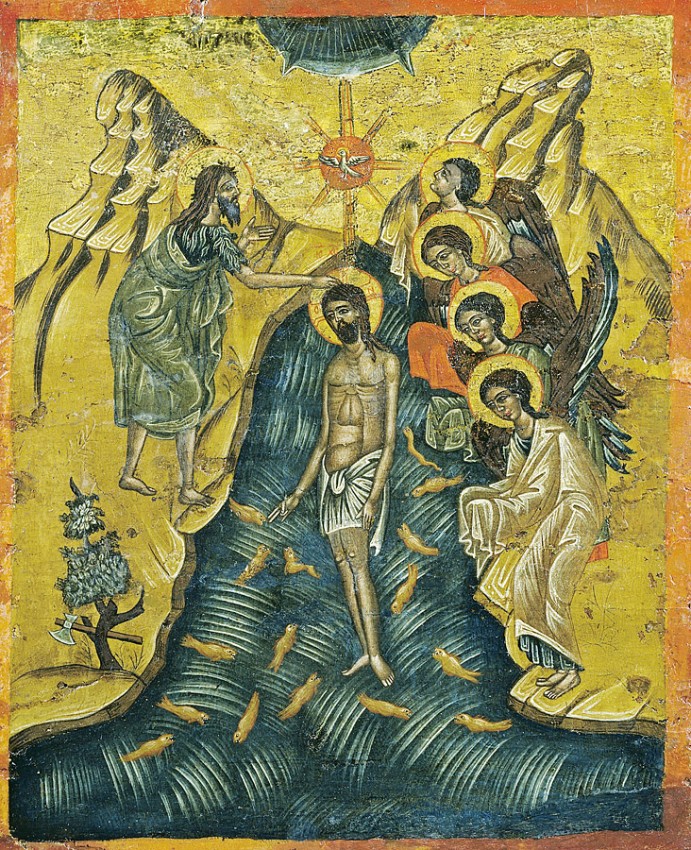

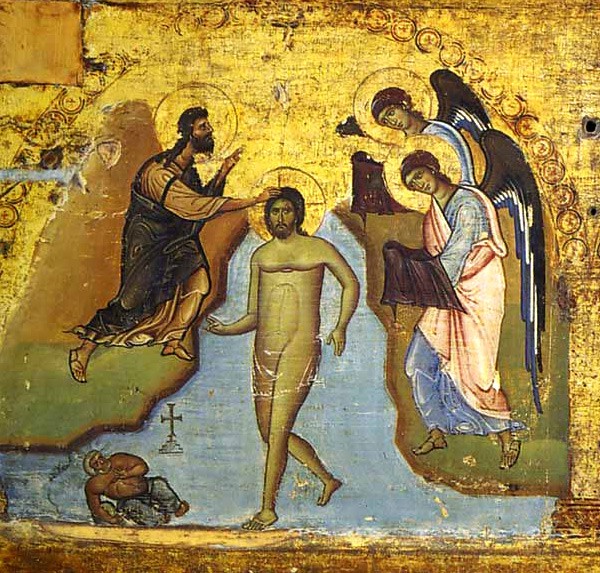

The Theophany is one of the most ancient feasts in the Christian calendar, originally celebrated together with the Nativity of Christ as one solemn feast honoring the Incarnation of the Word and the beginning of His earthly economy. Icons of the Theophany had already appeared in the first centuries of Christianity and recorded for us not only the Savior’s Baptism at the hands of St. John the Forerunner, but most importantly His manifestation to the world as the incarnate Son of God and a Person of the Holy Trinity, about which the Father and the Holy Spirit bear witness, the latter by descending upon Christ in the form of a dove. This is emphasized in the hymns for the feast: “When Thou O Lord wast Baptized in the Jordan, the worship of the Trinity was made manifest…” (Troparion to the feast). One of the most ancient depictions of the Baptism was preserved in the early Christian catacombs in Rome. Here, as in other monuments of the fourth to fifth centuries (for example, a mosaic in an Arian baptistery in Ravenna), Christ being baptized by the Forerunner is depicted as a beardless youth. Nevertheless, later Christ would generally be depicted in accordance with Church tradition—as an adult. The icons of the Theophany contain elements not taken from the Gospels. Thus, in the scene of the Theophany the artists mixed the personification of the Jordan River in the form of a gray-haired elder and the sea in the form of a woman swimming away. These images are based upon the text of the Psalm “the sea saw it and fled, the Jordan was turned back…” (Ps. 113:3). Furthermore, the Gospels do not inform us of the presence of angels at the Lord’s Baptism, although they were always depicted from the sixth to seventh centuries standing on the riverbank opposite St. John the Forerunner, and they usually occupied the right part of the composition. There were usually three angels bowing to Christ, and holding a napkin in their hands, like godparents at a baptism who receive the baptized from the font. Over the Savior standing in the water there has from ancient times been depicted a segment of heaven from which a dove descends to Christ—the symbol of the Holy Spirit and a ray of the “Trinitarian light”. By this is the moment of the manifestation of the divinity, the Theophany, accentuated.

Baptism__Transfiguration__Resurrection of Lazarus, an epistilion on the templon (a horizontal series of icons depicting the major feasts, on the board extending over the altar doors). Late 7th c., Sinai Monastery.

In all the icons of the Theophany, what draws most attention is the figure of the Savior and St. John the Forerunner, who places his right hand on the head of Christ. In the hymnology of the feast as in the icons, the theme is accentuated of the Lord’s receiving Baptism from His servant: “How does the servant place his hand on the Master” is sung in the troparion at the blessing of the waters. Christ’s pose varies. In early iconographic monuments His figure is presented strictly in a frontal view, and later a depiction in a slight turn and movement becomes more popular, as if Christ is taking a step. This is directly related to the Gospel text, where it is said that having been Baptized, Jesus “went up straightway out of the water” (Matt. 3:16).

Compiled by Svetlana Lipatova

Translation by Nun Cornelia (Rees)

Comments

Rhonda1/20/2018 6:55 am

There is nothing heretical about the 2 depictions (the 4th & 7th icons) even though they were painted by heretics. Both are interesting tidbits in the history of iconography. Western iconography actually remained very traditional long after the Schism & long after Western theology changed.

Julia1/19/2018 6:25 pm

Why is there an icon shown from the Arians (The Arian baptistery in Ravenna, 4th icon shown). Why is there a Roman Catholic mosaic from the 13th century (7th icon shown)? The Arians and Roman Catholics are heretics - why are these on an Orthodox site?