I should immediately clarify that I was a guest of Catholicos-Patriarch Ilia II of All Georgia. This is how it happened…

In the beginning of the 2000s, I, then a twenty-year-old young man, was studying at the Moscow Theological Seminary—a prestigious theological school, in which, at that time, guys from throughout the former USSR were studying. My class had a Georgian with an ancient Georgian surname. Sasha Sturua was his name. Sasha invited me one time, in our third year, to go with him to Georgia for the break. “Let’s go,” he said, “we’ll stay in Tbilisi. I know His Holiness well. He’ll meet us and help us. And we’ll travel to the holy places. St. Nina’s relics are there at Bodbe, and the Lord’s Tunic is there in the former capital Mtskheta. And let’s take Kolya with us. Let’s go.”

Kolya is my old friend. Sasha added him to our company to make it easier to persuade me. Basically, I agreed. This was at the beginning of the school year, but by the end of the year, the Lord, as so often happens, had adjusted our plans. Man, as we know, only makes suggestions. Kolya decided to get married in the summer, and said to me, “Have me excused.” Of course, I was sad, but this sadness was more than made up for by the exultant joy for my friend: Glory to God, his life was already coming together!

The main surprise was still to come. Our visas were already done and the tickets were already bought, and there was only a month left before the trip. Then Georgian Sasha came up to me and, with a completely calm look, declared, “Forgive me, I can’t go. My boss won’t let me go (he was a subdeacon). But don’t worry, you can go by yourself. Don’t worry about a thing, I will call the patriarchate and they will receive you. The main thing is for you to go to Tbilisi.” This was serious. I had never gone anywhere before, and especially not alone, beyond the borders of our vast Motherland, and such a voyage was not part of my plans. But Sasha’s words, with his wonderful charm, were so convincing that I, after a slight hesitation, agreed. The steps of a man are ordered by the Lord (Ps. 36:23).

The Moscow-Vladikavkaz fast train quickly got me to the capital of North Ossetia (there were no flights then), and together with my first gulp of Caucasian air, I tasted the unforgettable feeling of a journey beginning. I was quite confident that if I encountered any difficulties on the way, the Lord would grant deliverance, and my faith, made somewhat rosy by the good seminary life, would at least, through trials, acquire “its face.” And the Lord, I must say, gave me such a chance, for my adventure began almost immediately.

The shortest path from Vladikavkaz to Tbilisi lies through the Georgian city of Gori, before which you have to pass through the Russian and Georgian border posts. Thanks to the joint efforts of our Russian and Georgian brothers, the first problem appeared: It took more than twelve hours to get through the posts! This was in no way part of my plans, and seriously complicated achieving my goal. It was already after midnight when we got into Georgia.

From Gori to Tbilisi is about fifty miles, and driving along the Georgian desert road would have been easy and joyful if there hadn’t awaited me the wholly unjoyful prospect of winding up there late at night. But no matter—the Lord does not abandon—I believed. The half-empty bus sped through the deserted provincial towns, and I, in order to divert gloomy thoughts, tried to examine the examples of Georgian flora flashing outside the windows. But to divert, alas, did not work out, and the rain that began as we approached Tbilisi only added “gunpowder.” Having begun, it stubbornly refused to let up, and by the last station, it “beat” my mood, having become torrential.

So, at 2:30 AM I wound up on a deserted street of the capital of a country unfamiliar to me in the pouring rain (it’s a good thing I brought an umbrella). Well, hello, Georgia! If only my adventures had ended there, I would consider you the most hospitable country in the world. But my adventures, alas, were only just beginning.

At the bus station, the arrivals were met by a group of taxi drivers, who, having surrounded us, offered their services. My choice fell on an elderly Georgian—intuition advised me: If necessary, I can take shelter with him. We loaded my stuff into the car and drove off. However, we hadn’t even managed to go half a mile when a car with “blue buckets”1 caught up with us and forced us to pull over to the side and stop. Out of the car came a 6.5-ft.-tall Georgian with an automatic at the ready; he opened my passenger-side door and, presenting his “ID,” the officer ordered me to follow him with my stuff. Seating me in his car, the officers (there were two) first demanded my documents, which, of course, were completely in order. Then they got interested in my bag, which, after the “inspection” was deprived of two new shirts. The final agreement went like this:

“We’re going to the department now.”

“What for? What are my violations?”

“We’ll find them.”

“No, guys, let’s work this out here.”

“Okay, give us ten lari ‘on the nose,’2 and we’ll take you back.

I didn’t have a single lari (Georgian currency) on me yet, and the guys “kindly” agreed to take me to the nearest exchange place. I asked the taxi driver to wait for me a bit and headed off with the “officers” to the exchange. My head was spinning with the ironic “here’s Georgian hospitality for ya” and the sarcastic “serves you right, traveling abroad alone, brave guy,” but my heart (or the voice of God) told me that Georgia would still “bounce back.” Basically, after getting to the exchange place with the accompaniment of the two men with guns, I “paid the security guards” and was safely returned to my taxi. Thanks to them for that! According to our standards, they took quite a small amount!

The taxi driver had, as a I recall, an old Shesterka,3 which, without any special prospects, rushed me straight to the patriarchate. We arrived. It was early Saturday, and the patriarchal guard, displeased that we had disrupted his “Sabbath rest,” stiffly muttered:

“I don’t know, we didn’t receive anything about you. It’s better to come on Monday; there won’t be anyone today who can help you anyways.”

We had arrived. What to do? It’s good that my intuition with the taxi driver didn’t let me down. The taxi driver with the wonderful Russian name of Sergei invited me to his home, at least until morning. It was decided that I would stay with him until morning, and at nine we would return here. If it didn’t work out in the morning, then, as they say, “we’ll live until Monday.” Here was Georgian hospitality, without any quotation marks! We left. We didn’t drive long. The engine on the old Shesterka was “boiling;” and, unfortunately, for a long time. Sergei tried to revive the car, pouring cold water into the radiator, but nothing worked. We decided to wait it out somewhere off to the side until morning. We had already laid down to sleep and reclined our seats when suddenly Sergei jumped up and said,

“No, it’s not fitting, my guest can’t spend the night in a car. We’ll grab someone and ask for a tow.”

It didn’t take long to catch someone. Soon an Oka4 appeared, out of which emerged a man… no, a half-man. It was a man of forty years, who just had a stand with wheels below his waist, on which he rolled over to us. I’d seen such people in our Moscow subway, but I’d never seen them driving a car along the streets of the capital. This “wheelman,”5 Roma was his name, as it turns out, lost his legs during the Georgian-Abkhazian war in the beginning of the 1990s. But life forced him to drive. He adapted a car so that he could steer with one hand, the other responsible for the accelerator and brake. And that’s how he got to us. And what a vivid example it was for us, nearly healthy in body, but crippled in soul! We can’t even persuade ourselves to sacrifice our time (energy, means) for the sake of another in broad daylight, but this crippled man, who hadn’t given up, with a noble soul not only moonlights for his livelihood, but even finds time and energy to help others! Behold, edification without any words!

So Roma drove us home. At his house we were met by the good-natured Zinab—Sergei’s wife, who treated us to some splendid scrambled eggs. And I, already comforted by the sincere hospitality of these wonderful people and slightly lulled by the Georgian chacha,6 fell asleep and slept like a babe, certain that everything would be different in the morning.

In the morning, Sergei, already by then having “agreed” with his Shesterka, drove me again to the patriarchate. But, despite that it was a different security guard, as before, no one was expecting me there (!), and the prospect of staying another few days with the Georgian retirees became all the more real. And here occurred the first, although small, miracle, followed by the others. As Sergei and I, somewhat discouraged, were walking away from the patriarchal checkpoint, a young man came up to us and offered to help. He seemed to me to be an angel sent by the Lord, but in the earthly reality, he turned out to be just a seminarian of the Tbilisi Seminary. The building of the Tbilisi Academy and Seminary were located then (I don’t know about now) not far from the patriarchate, and this young Kakha “happened” to be nearby. After listening to my confusing story about the situation, he promised Sergei to arrange for me at the seminary, and I had to say goodbye to Sergei, who had already become my friend. The goodwill and hospitality of this true Georgian will always remain in my memory.

In the Tbilisi theological schools, just as in the Moscow schools, there was summer break then. Therefore, there was no one in the buildings except the guard. Kakha quickly arranged with him—he was from the same seminarians—and we, leaving my things with the guard, went to look for the seminary rector Fr. George, who could allow me to stay there. Fr. George, may God grant him health, was a very attentive and quick-to-help man. Having heard the story of my adventures, he offered the rather interesting and, probably, only proper option:

“Listen, you came to the patriarchate, not the seminary. The patriarch is serving at Sioni this evening. I’ll be serving there. Come to the Vigil and stand somewhere near the altar. I’ll find a time to call for you. You’ll go see the patriarch and tell him everything.

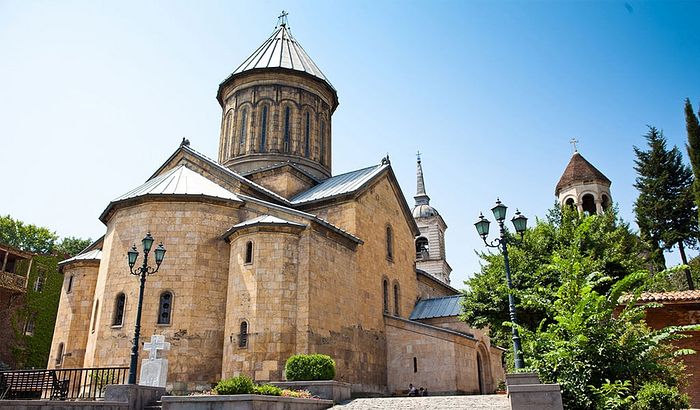

“Sioni,” known in Tbilisi as the Sion Cathedral, is named in honor of the Palestinian Mountain of the same name. It is located not far from the patriarchal building, and in those years was the main cathedral of the city. The small cathedral is visible from practically anywhere in old Tbilisi. But the main thing is not the size, architectural decisions, or frescoes, but the sacred objects: the cross of St. Nina—made from grape vines and the woven hair of St. Nina herself—and the head of the holy apostle Thomas. I arrived for the All-Night Vigil expecting an audience with His Holiness. I knew very little about Patriarch Ilia then. I knew that he became patriarch before I was born—last year marked forty years since the day of his election to the throne—I knew that he graduated from the Moscow Theological Academy in 1960 (a photo of his graduation is hanging in the academic corridor), and I knew that my classmate Sasha knew him very well. That’s all I knew about Patriarch Ilia. Thus my attitude towards the possible communication with him was more anxious: I’d never spoken face to face with a patriarch. How would I tell him about everything? And what should I talk to him about in general? That my friend suggested that I visit him and said they’d receive me joyfully there? That I’m a very important person—a seminarian from Moscow—and therefore I can come without an invitation?

The service went as usual, and, although everything was in Georgian, I (a seminarian!) understood where we were in the service. Somewhere around “Lord I Call” I entered into such a state that I already wanted to run out of the cathedral—not just from all the questions I didn’t know how to answer, but also because I could barely stand on my feet from lack of sleep and food over the previous twenty-four hours.

But then they started singing “The Lord is King, and hath clothed Himself with majesty,” and the “moment of truth” arrived—Fr. George came out of the altar and called me “for an audience.” I had to get a hold of myself and order my “cotton” feet to follow Fr. George into the altar. I must give due to this priest: He didn’t just briefly tell His Holiness about me before he called me into the altar, but, in the altar, seeing my condition, caught me and led me right to my goal! His Holiness was sitting in a chair to the right of the altar. I barely made it to him with my already trembling legs; I fell to my knees in front of him, took his blessing, and began to talk. My heavy breathing and extreme trepidation made my speech quite incoherent. I told him where I was from, said something about Sasha Sturua, who sent His Holiness his bow, and that Sasha, obviously, had not managed to get through to the patriarchate. I, of course, was embarrassed about everything I said—not just because I was an uninvited guest, but also because it was beneath the patriarchal dignity to be dealing with the personal problems of some Russian seminarian. But His Holiness deemed otherwise. Having heard my disjointed speech, slightly nodding his head, he asked in completely pure Russian:

“Where have you stayed?”

“So far, nowhere, Your Holiness.”

“Then you’ll stay with me in the patriarchate.”

He called his oldest subdeacon and began to tell him something, in Georgian now. He then said a few things to me, and I was left to pray in the altar until the end of the service.

It’s hard to represent the feeling I had then on paper. I received this as a manifestation of God’s grace to me, a sinner, for the trials I had survived in the past few days.

After the service I was told to go to the patriarchate building, not far away, where His Holiness’ oldest subdeacon met me and entrusted me to a middle-aged nun. The patriarchate (at least in that time) contained a female monastic community in its structure, which carried out its obediences there and celebrated the services in a house church. The nun immediately took me to a private room, already prepared for me, showed me the trapeza, and … took me to His Holiness Ilia himself. The waiting area was all covered with beautiful carpets, paintings of Georgian masters hung on the walls (if my memory serves me), and there was a massive dog lying at the door to his office. I don’t know anything about breeds, but it was something like a huge Rottweiler. At our arrival, he continued lying calmly, just turning his head towards us for a bit.

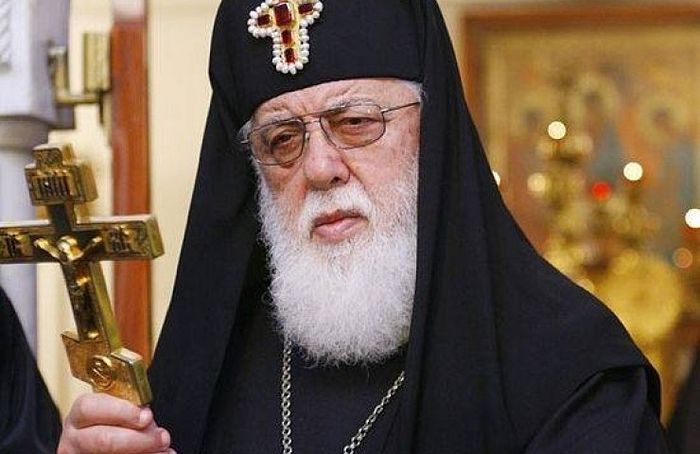

The patriarch came out a few minutes later. His beautiful riassa and the Panagia hanging on his chest gave him a modest figure, an especially majestic site. The expression of open amicability never left his face even for a second. He blessed me again and asked me, “How have you settled in?”

“Thanks to you, Your Holiness, very well.”

“Did you take my guest to the trapeza,” he asked the nun.

“Yes, Your Holiness, I showed him.”

“Don’t show him, but take him and feed him.”

“Yes, of course, Your Holiness. I’ll do that now.”

After that, the patriarch handed me an envelope with the words, “This is for your personal expenses.”

“Thank you, Your Holiness.”

I bowed to His Holiness the patriarch and left with a feeling of reverential gratitude. For me, as a student of a seminary, such a meeting, I remember, had considerable pedagogical value and left a feeling of having learned a valuable lesson.

I stayed at the patriarchate for about a week. The money the patriarch had given me—there was about 100 lari in the envelope (about $130—a lot of money at that time)—was enough for trips around the city and its surroundings, and for fruit. It’s Georgia after all—how can you stay here without fruit! For example, two pounds of peaches or apricots cost about $1.50 (in Russia it would have been three times more expensive). But despite the length of my stay near the patriarch, I only had the chance to have one small conversation with him. The nun’s community of the patriarchate gathered to read the prayer rule every evening in the house church, which His Holiness Ilia participated in. I also went to the prayers sometimes—only sometimes because they were pretty long and read in Georgian. After the main prayers they had a cross procession with icons around the church. The path led through a garden where I relaxed sometimes with a book in a hand. One time, while I was sitting on one of the benches in the garden in the evening, I heard the nun’s prayerful singing. The cross procession was getting closer. His Holiness was also walking with the nuns. During one of the stops, not far from where I was sitting, the patriarch came up to me and asked,

“How are you enjoying your stay with us?”

“Thank you, Your Holiness, for your hospitality.”

“Okay. Get some rest and relaxation.”

I thanked His Holiness not just for the reception and the generous attitude towards me. I also thanked him for the amazing trip to David-Gareji Monastery that he helped to organize, and for the visit to ancient Mtskheta, with its amazing holy sites. But especially for that spiritual lesson which was taught to me…

Possibly (and even very likely), some readers will not see anything amazing or edifying in this story. However, every believer knows that our life consists of small (and big) “random” “puzzle pieces,” from which is composed the beautiful and picturesque “canvas” of our salvation. Remove some small “puzzle piece” and the “canvas” becomes defective. That means there are no accidental “accidents.” For the providence of God is “the continual action of the omnipotence, wisdom, and goodness of God…”7 Every event in our life is the activity of God, Who, according to St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov), directs the life of man in every little thing, because every little “trifle” has its own spiritual lesson. We just have to understand it.

What did I get out of this trip? A whole lot. First, from my own experience I learned that difficult circumstances in a man’s life are a means for the Lord to reveal to him His presence. If you have fallen into a difficult situation and you don’t know what to do, wait for the “manifestation” of the Lord. Know that He will surely send a person or situation, unexpected for you, to help you. Second, I discovered for myself an affirmation of the famous proverb, “words edify, but examples attract.” The examples of sacrificial Georgian hospitality revealed the difference between declarative and true Christianity, explaining to me, to my shame, that “on my account” there was as yet only a “declaration,” but true Christians are the retired Sergei and Roma “on wheels.” Finally, the example of His Holiness Patriarch Ilia—a saint (according to my deep conviction) of our times—teaches a lot. Let each think for himself about what exactly.

For me, the example of His Holiness Patriarch Ilia will always remain a bright symbol of Georgia, lovingly embracing even uninvited guests.