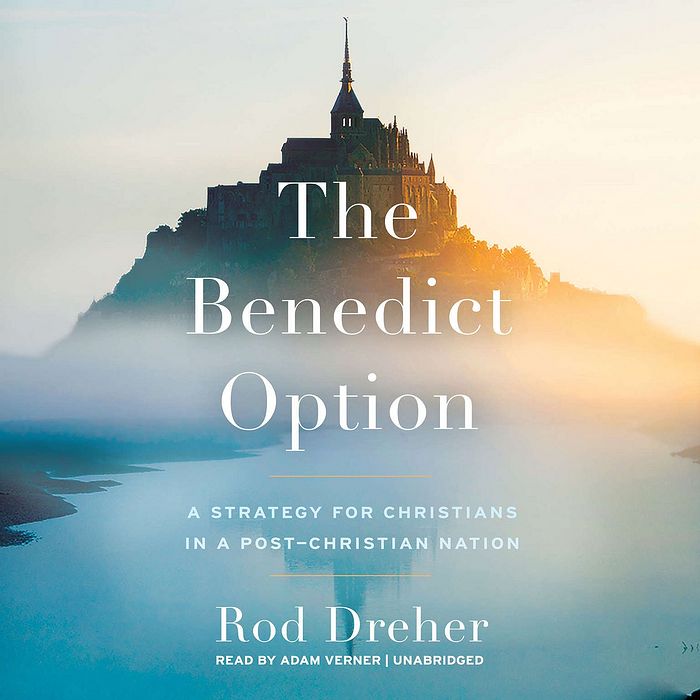

Some reflections on the sensational book by an Orthodox American Rod Dreher, The Benedict Option, the post-Christian world, and some parallels with the reality in Russia.

Rod Dreher is an extraordinary man. A well-known American journalist and conservative, he was raised a Methodist and converted to Roman Catholicism as an adult. Now Rod is an Orthodox Christian. With his apocalyptic ideas, today Rod may seem to be a neophyte or a radical from the generation of Orthodox patriots of the 1990s. Some may find a subtle connection with Fr. Seraphim (Rose)’s penetrating insight in his works.

Rod Dreher believes that modern Christians have lost a cultural war. In his opinion, in order to survive and preserve their faith they should distance themselves from the world for a time and switch from the public sphere to the inward reality of the life of modern communities. The journalist feels confident that the spiritual and intellectual power of Christianity is now being undermined. That is why, according to him, Christians need to isolate themselves, to increase the level of education in their own environment in general, to make efforts to create commercial enterprises, based on the foundation of firm spiritual convictions. Otherwise, Dreher believes, a generation later Christians will begin to disappear and lose their faith.

Of course, Rod Dreher speaks of the religious space of the West—the USA and Europe. However, we should admit that, despite all the ongoing serious changes, the modern world is still influenced by mass culture of Western countries. Whether we like it or not, Russia is no exception. The Western pop culture has become an integral part of the lives of many people. These images, designs, the music, cinematography and language permeate nearly every aspect of today’s society. If you enter a cozy coffee shop or an ordinary clothes shop that play background music permanently, you will immediately note the culture and language of the singers. On the feast of the Nativity of Christ the choir of one of the cathedrals of my native town performed “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” [a popular traditional English Christmas carol from the “West Country” of England.—Trans.] just before Communion. But I have not given this example in order to criticize—I just want to demonstrate that Western culture is truly permeating the fabric of our Russian society (both the secular and the Church “segments” of it). Therefore, the negative processes that we can observe “overseas” well may spread to our country.

A committed conservative with a strong civic stand, Dreher considers Christians living in the USA and Europe as one community with the same cultural origins and similar issues (and it is difficult to disagree with this idea). Perhaps on account of all this he suggests taking the behavioral model and experience of St. Benedict of Nursia (a saint who is venerated by both Orthodox and Roman Catholics) as a guiding principle in the post-Christian era.

American right-wingers think that they suffered “a cultural defeat” in the 1960s during the so-called sexual revolution. Dreher is convinced that it had happened much earlier, namely in the era of the Renaissance. In the author’s judgment, it was then that the Western world lost its Christian roots, however dramatic these words might sound. One may see it as an allusion to the events in Russia. Some representatives of the conservative wing in Russia believe that the Revolution of 1917 marked the end of the Christian civilization in this country. Meanwhile, a tiny minority of conservatives argue that the process was triggered by the Church reform of Patriarch Nikon and Tsar Alexis, accelerated under Emperor Peter I and by 1917 spilled over into a revolution due to the contradictions and the extinguishing of faith.

Dreher points out that the process of de-Christianization was aggravated by the advent of consumerism and the age of the scientific and technical progress. And no wonder: excessive access to the basic (and not only basic) necessities of life, an increase of possibilities in life and amazing medical breakthroughs gave rise to human pride.

In Dreher’s view, American Roman Catholics actually adhere to some form of Protestantism. Without going into details it can be formulated this way: “You just need to be a good person to enter Paradise.” Dreher is positive that they have the power and all possibilities of returning to public space and reversing the situation with the de-Christianization, but… for some unknown reason have failed to do it over many decades. As a matter of fact the U.S. Catholics sometimes take even more liberal stances on various social issues than their fellow-citizens.

The idea to write the book The Benedict Option was conceived under the influence of a book entitled After Virtue by Alasdair MacIntyre. The key moment was the idea that the society of the era of the Renaissance chose reason as the basis of morality. The rationalism of this approach led to a moral fragmentation—that is, different interpretations of ethics. That moment is considered to be crucial in the process of the atomization of the Christian civilization that lasted centuries (and Russia is no exception). The philosophical paradigms and approaches of modern people are so diverse that they prevent them from agreeing on a number of issues. It applies to people in the Church as well. And if we take into account the effect of “society in fluid modernity” (according to the Polish-born British philosopher Zygmunt Bauman (1925-2017), it is an individualistic society, cut off and isolated from its traditions, which has a personal “ego” as its cornerstone), then we will see the most deplorable results.

I recall how on Great Saturday of 2016 in my native town, volunteers collected signatures supporting a ban of abortions. I had a chance to appraise the sentiments of the faithful from three parishes. And it was sad that people who believe in God and were regular churchgoers expressed diametrically opposite points of view on abortions. Similarly, there is no unanimity of opinion on the controversial mass cultural events organized by some parishes and dioceses, which provoke a wide debate on the internet. Orthodox Christians even demonstrate disagreement about whether or not it is appropriate to allow reading rap on the ambo and performances of child ballet dancers in the church.

The author suggests a “strategic retreat” in the context of “the collapsing empire”. Prayer, order in everything, labor, an ascetic way of life, and communal life will give Christians a chance to preserve their faith. Dreher also calls for practice and not profuse talk only. In his opinion, Christian schools and businesses should be founded on the basis of communities. The writer holds an absolutely uncompromising position regarding secular education. Modern Christians strive to organize their children’s education so that they could be successful in their adult life. However, children are quite often susceptible to the spirit of the age. Without a strong moral foundation they are not always able to resist this spirit. The author provides a disarming example: how to protect your children from the influence of their peers with smartphones, with an access to the internet and all sorts of information? It is hard to argue with that.

The journalist, taking St. Benedict of Nursia and his community as a model, suggests a kind of “monastic way of life” as an ideal for lay-people. It immediately reminded me of the Edinoverie tradition [the “Edinovertsy” are Old Believers in communion with the canonical Church in Russia] within the Russian Orthodox Church. Hieromartyr Simon (Shleev), a brilliant apologist and advocate of the “old piety” of the Synodal period, rightly characterized the way of life of Edinoverie parishes as “monastic”. Truly, on the face of it the “Benedictine model” and the “Old Ritualists’ tradition” in Russia have much in common.

While American conservatives traditionally searched for “the enemy outside”, “the apple rotted from the inside”, as the Russian saying goes. The author points out the neglect of the Christian education of children and total de-Christianization of American society. By the way, speaking of the latter, Dreher cites the appointment of a practicing Catholic as the US Supreme Court Justice as an example. This provoked a barrage of criticism from various commentators and observers who claimed that “religion will hinder the appointee from being a good judge.”

In the post-Christian world, “the church can't just be the place you go on Sundays—it must become the center of your life,”1 writes Dreher, and his words “rub salt into our wound”, as the saying goes. Is the holy faith our way of life or just one of our hobbies and “spheres of activity”? This question is key in one’s religious self-determination. In truth, we realize that Christians must remain Christians regardless of the epoch we live in. However, the faithful need to cultivate wisdom and develop concentration in order to defy the aggressive spirit of the age.

Beyond all doubt, The Benedict Option provides us good food for thought. The value of this book is not in alarmist sentiment, but in its highlighting of some useful practices of Christian life, which, first and foremost, are meant for every individual and aimed at the perfection of the community of the faithful. Focusing on your inner state, on your way of life and that of your community, on asceticism and your spiritual education is useful for any Christian even in a period of “the empire”, when “the weather is fine” and “the sun is shining”, figuratively speaking. The unforgettable words of St. Seraphim of Sarov, “Acquire the spirit of peace and a thousand souls around you will be saved”, remind us (who are sometimes carried away by “external activities” in the Church, though nobody denies their role) that nurturing and caring for the soul is of paramount importance to Orthodox Christians. For, behold, the Kingdom of God is within you (Lk. 17:21).

See http://www.theamericanconservative.com/dreher/cardinal-marx-gay-blessings-benedict-option-catholic-germany/

1) Christians worldwide may not only have lost the cultural war years ago, they are now losing a moral war (having failed to stand up for the rights and wrongs in Holy Scripture, and subsequently will lose a religious wars as well, to Islam.

2) Christian Deterioration can be seen as a descent onto lower plateaus of God-Avoidance. The corruption, errors, and poor spiritual life of the Western Church during the Dark Ages was the first; the Renaissance was the second; the Bolshevik evolution, world wars, and counter-culture/sexual revolution of the 20th Century was the third.

3) Christian Communities? Yes!

===