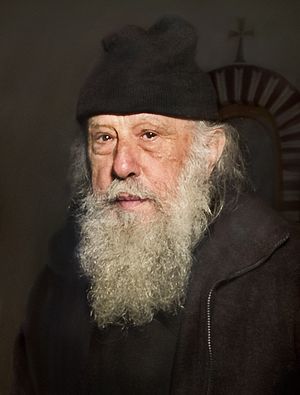

A Russian book, Meetings with Elder Nazarius, was recently published in Moscow and dedicated to Archimandrite Nazarius (Terziev) from Bulgaria who reposed in Sofia in 2011. This is what Metropolitan Longin of Saratov and Volsk wrote about him: “I confessed to Fr. Nazarius and want to say that he was a man of a proper spiritual disposition—absolutely sober, without any exalted emotions and at the same time a strict ascetic. He lived at the Archangel Michael’s Monastery for over forty-five years, twenty of which he spent there alone. He did everything himself, from daily chores necessary for the monastery’s maintenance to regular services. One chorister used to come to him for the Liturgy and all other things were carried out by Fr. Nazarius. And it lasted twenty years in succession! In winter this mountain monastery was often buried under snow, so nobody could get there for several weeks, and the elder would remain in solitude absolutely alone without any contact with the outside world.

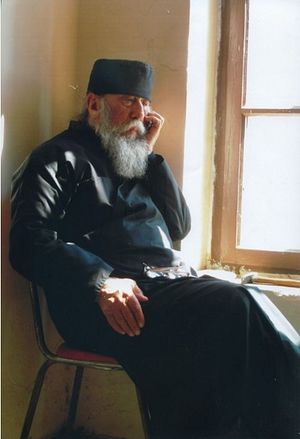

“Fr. Nazarius was always very good-natured and open; he was ready to welcome and receive people at any minute and would immediately put down whatever he was doing.

After my return to Russia [Metropolitan Longin spent four years in Bulgaria: from 1988 till 1992.—Ed.] the first books on Elder Paisios the Athonite were appearing here. As I was reading his talks I felt something very familiar in them, that he reminded me of somebody. A little later I realized that he reminded me of Fr. Nazarius! If I can put it that way, Fr. Nazarius was ‘the Bulgarian Elder Paisios’. His words were very simple, but he often used figurative language. The elder spoke and behaved very naturally and never pretended to be someone else. He would always speak to the point, and there was so much depth, so much spiritual wisdom in his naturalness and simplicity!”

Below we offer our readers several extracts from the book Meetings with Elder Nazarius.

* * *

Archimandrite Nazarius’ secular name was Nikola Stoykov Terziev. He was born on November 27, 1933 in the Bulgarian city of Nesebar to the family of Stoyko and Maria Terziev—a wine-grower and a housewife.

<…>

Forty days after the funeral of little Nikola’s dear mother elapsed and one day he saw his father clean-shaven. At that time men in Bulgaria usually did not shave as a sign of mourning for their newly-deceased family members. Soon his father remarried and a new woman came to live in their house. Her name was Maria too. She took her two daughters and one son with her. With time three more children from this union were born: again two daughters and one son. Thus the most difficult period in the lives of two orphans, Nikola and his sister Velichka, began.

Recalling their childhood, Fr. Nazarius’ sister used to say that her little brother looked like a ragamuffin and would wear tattered clothes and wooden shoes. Their stepmother would hide bread from Velichka and Nikola under the mattress and compelled them to work hard as though they were adults. Once the stepmother took little Nikola to work in the field under the scorching sun but did not take any water with her. So the boy was forced to drink from some puddle in order to quench his thirst…

Orphans are under the special protection of God. Orphaned children don’t feel abandoned and rejected, instead they feel the mercy of God. Fr. Nazarius used to say that when he was an orphaned boy he was chosen by the Archangel Michael and lived under his protection. The Church of St. Michael was his real home. A stable was attached to the church, and one day Nikola went inside it to look at the horses. But one horse suddenly savaged the child so he collapsed and fainted. No one saw the incident or could help the boy, and it was only through the invisible intercession of the Archangel Michael that Nikola escaped sure death under the animal’s hooves. Another time he nearly drowned in the sea, but the Almighty saved him again.

Fr. Nazarius served in the infantry in the city of Smolyan…

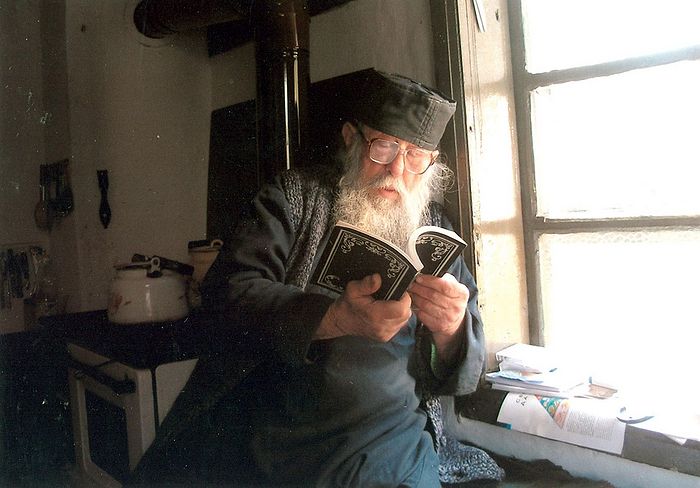

“Praying in the headquarters was bliss for me! [after an appendectomy the future elder had to serve at the unit headquarters.—Ed.]” the elder used to say. “I would pray for hours. As soon as the officers were off, I would lock myself, take my icons out and begin my prayer rule. Even at the monastery where I was to live later I did not have such great joy of reading my prayers as I did then. Do you know what my Vespers service was like? If you looked out the headquarters’ window you could see a crossing and every evening at 5:50 p.m. a priest would walk across it. He would appear from behind the house across the street, cross the road and pass out of sight round the other corner. He was going to serve his Vespers! Each time I could see his black cassock only for a moment, but it was as a blessing for me. At that very minute I would begin my own ‘Vespers’ by reading the prayers that I knew by heart, such as the Trisagion Prayer, the Entrance Hymn (“Come, let us worship and bow down…”), Psalm 103, ‘Lord, I have cried unto Thee’ and so on. And I felt as if I had stood through an entire service at church!”

In those years, Bulgarian clergy were forced to comply with the requirements of the Communist authorities with regard to their appearance outside church, in order to prevent people from remembering God and the Holy Church by their appearance. They would wear close-trimmed beards, secular black suits (it was mandatory), and hats with brims. This is what the Bulgarian clergy looked like, but not that unknown priest who was sent by God to the future monk to strengthen his faith.

* * *

On his return to Sofia he soon found a job, and his life began to run its course, as it had been before the army. He worked as a cook’s assistant and as a waiter in a factory canteen. The future elder worked at a surveying and cartography department for six years and had the unusual profession of chief globe-maker. He always was a conscientious worker, yet he was tormented by doubts: on the one hand, he wanted to support his sister and her family, but, on the other hand, an inner voice kept calling him to the service of God.

<…>

The young man’s seeking soul felt the vanity of human endeavors without God, and the life in that atmosphere got darker and more cheerless, becoming purposeless and, therefore, meaningless. However, a man’s foes shall be they of his own household (Mt. 10:36). His sister Velichka and her husband discouraged him from withdrawing from the world. An inner conflict between his attachment to them, their disinclination to see him a monk and his own longing for monastic life kept tormenting his soul all the time. Gloomy thoughts pestered him day and night. One night he had a dream: “There was a rock in front of me. I was trying to climb it. I was moving slowly, dripping with sweat, with my arms covered with scratches. I was trying to cling onto rock ledges. Stones were rolling down from under me thick and fast, so I suddenly fell down, unable to hold on…”

* * *

If you happen to be present at a monastic tonsure, you will remember this service forever. Monotonous singing, with monks lined up in pairs slowly proceeding towards the altar with burning candles in their hands. Behind them the mentor of the future monk, dressed in a long black pleated mantia (mantle), leads his spiritual son to the middle of the church. The novice falls on his back with his arms outstretched as a sign of his death to the world at that very moment. The elder covers him with his mantle. Then the novice kneels before the cross and the Gospel. Next he takes his monastic vows, while all those present are listening with bated breath…

The moment came to give the newly tonsured monk a name, and the bishop asked Fr. Evlogy about the new name of the novice. But Fr. Evlogy… forgot it! Then he began to fish for a note with the name in his pockets, but in vain. Fr. Gelasy who was standing near quickly found a way out, saying, “Nazarius!” Thus the bishop tonsured him a monk precisely with this name. As it turned out, Fr. Nazarius wanted to have the monastic name “Nectarius”, but the Lord wanted him to bear the name “Nazarius”.

* * *

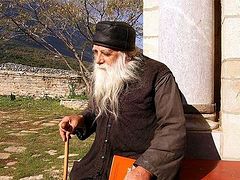

Several years later, Fr. Nazarius became abbot of the abandoned Kokalyan Monastery, and its only monk.

Fr. Nazarius had to officially receive the monastery together with the inspector of the Metropolia of Sofia Stefan Markov (a famous choir singer who later became a protodeacon) and Vasil Vylkov. But first he needed to inspect the monastery. The natural obstacle was its utter desolation. The only solid building there was the Church of the Archangel Michael, with its glassless windows resembling empty eyes sockets, whose sole “occupants” were swallows. No entrance to the church was accessible, so they had to get inside through a window, using a wooden ladder that they hastily knocked together. The new “owners” of the building, fearing for their nestlings, were skimming over the unwanted guests’ heads in terror.

There was nothing to make an inventory of in the desolate church but swallows’ nests with which the church walls were dotted. There were very dilapidated structures, most probably half-ruined sheds, adjacent to the church. There were Russian stoves with benches inside some of them, absolutely useless in the buildings without walls. The monastery’s former monks—both Russian monks who sought for the salvation of their souls and forced emigrants that left Russia to escape the Soviet Government’s persecutions—had long gone. The last Russian monk was then dying at some hospital far away.

* * *

Fr. Nazarius lived in an old corner room (into which drafts came from all sides) for the rest of his life, refusing to move to a new building when it was constructed later. When he did not use his stove for heating the cell in winter, it got extremely cold inside and even water in a cup was covered with an ice crust. The elder would leave the faucet dripping overnight to prevent the pipes from freezing, and by the morning splashes of the leaking water usually turned into one frozen chunk. Towards the evening icicles would appear on the ceiling. One morning, Fr. Nazarius woke up feeling some movement in his beard. It turned out that a mouse had hidden in his long beard in order to escape the cold. Another time while Fr. Nazarius’ spiritual children were talking with him in the kitchen, they spotted a snake’s tail, sticking out of the cell floor.

* * *

Right after the democratic changes in Bulgaria in 1989 and until the early 2000s, people seeking faith kept coming to the monastery. Sailors and scientists, artists and ordinary people from Veliko Turnovo, Burgas, Varna and all over Bulgaria climbed the high mountains to reach the monastery and hear the elder’s counsel. Fr. Nazarius received all with fatherly love; he baptized people, heard their confessions, married them in church and gave them advice. The Lord chose some of them as monks, others as priests, and others as preachers and missionaries. In that environment many young people found their soulmates, got married, became parents and grandparents. Six couples had their children baptized with the name “Nazarius” (after the elder) or “Michael”, in honor of the monastery’s heavenly patron. But the elder did not encourage parents to name their kids after him, instead recommending them to name their little ones after their grandpas or grandmas.

It was obviously the most fruitful period of Fr. Nazarius’ ministry as an elder. Over that period he nurtured and trained as many as thirteen monks: now one of them is a metropolitan, and five of them are monks on Mt. Athos where the elder sent them in the mid-nineties to help preserve monastic life in the Bulgarian Zographou Monastery. The rest of them became abbots and monks of restored monasteries. Dozens of his disciples now serve as parish priests in the province’s churches. Renowned theologians would come to Fr. Nazarius for spiritual counsel, some of them are currently professors at universities in Bulgaria and abroad. The elder taught them genuine theology in the example of his own monastic life.

The brethren of Kokalyan Monastery included the theological faculty students, seminary students, artists, painters, restorers, doctors, philologists, philosophers, lawyers, economists, chemists, and engineers. After all, monastic communities exist in order to unite people with diverse areas of knowledge, interests and traits for one common purpose. Serving God “in the front line”—that is, in monastic life—was something that attracted individuals with practical jobs too. Monks with engineering education at Fr. Nazarius’ monastery were so numerous that they could form a whole bureau. But under the elder’s guidance they didn’t seek for application of their knowledge, but wanted rather to find their path to God. And two of ten engineers eventually became monks.

One of them once compared Archimandrite Nazarius with a ship moving towards eternity. A monk labors and struggles on the border of two realms—the physical and invisible ones, between earth and heaven, as a heavenly man and earthly angel—just as a vessel sails on the border of two media, namely water and air.

All these people who had initially been inclined to pursue their careers and set goals for their lives began to realize the futility of all this compared with eternity. Each of them walked his own path in search of this truth… And they came to the elder to absorb his spiritual wisdom.

* * *

The monastic way of life presupposes renunciation of the world, solitude, and entails a barrier between a monk and the world. But Kokalyan Monastery of the Holy Archangel Michael, chosen by the elder for this podvig [spiritual labor in Russian], was very close to the capital city (which was being engulfed by a spiritual vacuum), and this determined Fr. Nazarius’ path of salvation in many ways. Hiding from the world, he remained available to us laypeople, and through his eremitic life he taught us to live in the world within permissible boundaries and with no extremes. He was an uncompromising soldier of Christ and struggled with the decadence in the society. He believed that a family man must wholeheartedly devote his life to the service of his family, a priest must be a priest and nobody else, and a monk must always be mindful of the purpose of monastic life.

It was his life path preordained by God—a ministry as a spiritual mentor. This is the mission of any confessor: to guide his spiritual flock under the protection of the cross of the Lord.