This early Orthodox saint, sometimes known as “St. Felix the Burgundian”, has long been venerated as the enlightener of East Anglia, one of the seven ancient kingdoms that formed most of what is now England. All these pagan kingdoms, founded by the invading Angles, Saxons and also some Jutes and Frisians, were established by the late sixth century, and over the seventh century embraced Orthodoxy one after another. St. Augustine of Canterbury, a Roman, is credited with being the first to bring Orthodoxy to these peoples and he is venerated as the apostle of Kent. St. Birinus, a Lombard, was responsible for the enlightenment of the kingdom of West Saxons. And it was a Burgundian from Gaul, St. Felix (the name means “happy” or “fortunate” in Latin), who converted the East Anglians. They lived on the territory of the present-day counties of Norfolk (“the northern folk of Angles”), Suffolk (“the southern folk”) and part of eastern Cambridgeshire. Today this region is still called East Anglia after the ancient kingdom. Most of the information that we have about St. Felix comes from the Venerable Bede’s History of the English Church and People, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the twelfth-century Ely Chronicle along with numerous early traditions. In the twentieth century the figure of St. Felix was rediscovered among many English people; a number of prominent academics researched this saint, and a priest of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, Fr. Andrew Phillips, wrote a booklet on this saint. Let us recall his life and heritage.

The Romans founded a number of cities and fords in what is now East Anglia in the first and second centuries A.D. Though situated not far from the important cities of Colchester (Camulodunum), and London (Londinium), this region was then considered as the backwoods. The first waves of Anglo-Saxon settlers appeared here after the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, though others had even before been recruited into the Roman Army and lived here. Many of their first villages were built along the River Deben in Suffolk. The dynasty of East Anglian kings was called the Wuffingas after the chief named Wuffa († c. 579) who is regarded as its founder. The royal seat of the East Anglian kings was at Rendlesham (Suffolk). They had a famous royal cemetery at nearby Sutton Hoo, which was rediscovered only in 1939 and is notable for its ship burials.

The first prominent king of East Anglia was Redwald (ruled 599-625), Uffa’s grandson, who was buried at Sutton Hoo. He was the first East Anglian king to convert to Christianity. He was baptized by the holy King Ethelbert of Kent and after the latter’s repose he became the ruler not only of East Anglia, but also of Kent and other lands, with his dominion spreading to most of England. But Redwald’s story was indeed sad. According to St. Bede, “Redwald had been admitted to the sacrament of the Christian faith in Kent, but in vain; for on his return home, he was seduced by his wife and perverse teachers, and turned back from the sincerity of the faith; and thus his latter state was worse than the former; so that, like the ancient Samaritans, he seemed at the same time to serve Christ and the gods whom he had served before; and in the same temple he had an altar to sacrifice to Christ, and another small one to offer victims to devils… The aforesaid King Redwald was noble by birth, though ignoble in his actions.”1

Redwald died “half-Christian and half-pagan” and was succeeded by his son Earpwald who under the influence of the saintly king Edwin of Northumbria fully embraced Christianity. However, he was soon murdered by a pagan and three years later was succeeded by his stepbrother, St. Sigebert—the first saintly ruler of East Anglia. When Redwald was alive, Sigebert was exiled to Gaul where he made his residence in Burgundy. It was here that Sigebert was baptized, became a pious Christian and obtained his education. And here we first meet our saint—Felix the Burgundian, who became St. Sigebert’s spiritual father and instructor in Gaul.

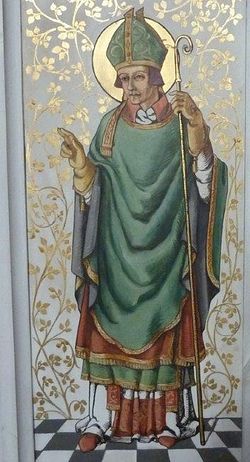

Wall Painting inside St. Andrew's Church in Soham, Cambs (photo kindly provided by the Soham church)

Wall Painting inside St. Andrew's Church in Soham, Cambs (photo kindly provided by the Soham church) In 630, St. Sigebert was recalled back to his native East Anglia after some years of instability to rule his kingdom. Beyond all doubt, the king wholeheartedly wanted his spiritual mentor to go with him and help him bring his compatriots to Christ. According to two different versions, St. Felix either moved to England together with Sigebert or came later. At that time the See of Canterbury was ruled by the holy Hierarch Honorius (feast: September 30 / October 13), who had come to England from Rome in 601 to reinforce St. Augustine’s mission and served as the primate of the English Church from 627 till 653, having served in the country for half a century. This illustrious archbishop energetically encouraged and supported missions in various parts of the country, namely those of the Irish St. Aidan in Northumbria, Sts. Birinus and Agilbert in Wessex and, finally, St. Felix in East Anglia. Soon after his arrival in England Felix was invited to Canterbury where Honorius consecrated him bishop and gave him his blessing for a large-scale mission among the East Anglians.

St. Felix sailed north from Kent and eventually reached his destination. Traditions connecting Felix with numerous East Anglian locations abound, but what is really known is that this saint for seventeen years tirelessly and self-sacrificingly labored in the kingdom despite many dangers and difficulties, converted many of its inhabitants to Christ, founded a bishop’s see with a cathedral, a seminary-school, several monasteries, and many churches, chapels and erected crosses in the east of England. And he performed numerous miracles. This is what St. Bede wrote about Felix’s ministry, “Sigebert, a most Christian and learned man…, made it his business to cause all his province to partake (of the faith) as soon as he came to the throne. His exertions were much promoted by Bishop Felix, who coming to Honorius, the archbishop, from Burgundy, where he had been born and ordained, and having told him what he desired, he sent him to preach the Word of Life to the nation of the Angles. Nor were his good wishes in vain; for the pious husbandman reaped therein a large harvest of believers, delivering all that province (according to the signification of his name, Felix) from long iniquity and infelicity, and bringing it to the faith and works of righteousness, and the gifts of everlasting happiness. He had the see of his bishopric appointed him in the city of Dommoc, and having presided over the same province with episcopal authority seventeen years, he ended his days there in peace.”2

Although it is known that in East Anglia Felix established a bishop’s see and a school, where teachers from Canterbury taught, pupils from all over the region came, and the education system was arranged according to the Gaulish model, we do not know exactly their locations. Researchers are still arguing as to where they were situated. Historically “Dommoc” mentioned by Bede has been associated with Dunwich—a coastal village near the town of Felixstowe in Suffolk. In the past Dunwich was a large town, a famous port and commercial center that at its peak had a bishop’s palace, a king’s palace, eight churches, two monasteries, five religious houses (including Knights Templar), three chapels and two hospitals, but over the Middle Ages much of it was submerged under the sea and now Dunwich is just a tiny hamlet.

According to another version, “Dommoc” was today’s Felixstowe, like Dunwich also on the North Sea. (Today this beautiful town is the largest container port in the country). The name “Felixstowe” means either “the holy place of St. Felix” or “a grassy place” (yet another version is that it was called after a local landowner). In the first millennium Felixstowe was a small village that was not even mentioned in the Domesday Book [the first survey of the lands of Britain carried out by the commissioners of William the Conqueror in 1086]; however, with time Dunwich disappeared, while Felixstowe began to develop rapidly from the nineteenth century on. Part of Felixstowe was called Walton, “the settlement of the Britons”, near a former abandoned Roman fort where St. Felix might have founded his main center. At least it is known that a local chapel was dedicated to St. Felix and the site was important; but now the fort has disappeared under the sea.

This has been considered as a candidate for “Dommoc” simply because of its name. When Felixstowe was just a village, Walton was a prosperous small town, though now the former has swallowed the latter. St. Felix certainly built a church in Walton in honor of the Mother of God, the successor of which stands there to this day (in the Middle Ages its second patron was St. Felix). The present St. Mary’s Church was largely reconstructed in the nineteenth century.

Another, though less possible candidate, is the part of Felixstowe called Old Felixstowe, where the ancient Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, which was restored in the nineteenth century, has stood from the time of St. Felix, who undoubtedly founded it. Whatever the truth, both these settlements—Felixstowe and Dunwich—have been closely connected with and kept the memory of Felix for nearly 1,400 years. All the more so as Felixstowe sits at the mouth of the Rivers Orwell, Deben and Stour, close to the sea, and near the royal palace at Rendlesham.

In his labors as evangelizer Felix was assisted by St. Honorius and the pious and wise King Sigebert. Felix’s episcopacy coincided with the long rule of the ferocious, militant pagan King Penda of Mercia (central England), who regarded each English king of some influence as his personal enemy and more than once attacked other kingdoms, killing several righteous Christian kings who are ranked among the saints. East Anglia was seriously attacked twice over the period of St. Felix’s ministry; in the first of them Sigebert, who by that moment had become a monk, was martyred by the Mercian pagans in 635. Sigebert was succeeded by the pious King Anna of East Anglia, who supported the mission of St. Felix in all possible ways. This ruler had six holy children, the most famous of whom was St. Etheldreda, the first abbess of Ely. Significantly, it was Felix who baptized Etheldreda, the most illustrious of all East Anglian female saints, and instructed her in her youth.

Depiction of St. Felix on the screen of St. Andrew's Church in Great Ryburgh, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Great Ryburgh church)

Depiction of St. Felix on the screen of St. Andrew's Church in Great Ryburgh, Norfolk (provided by the churchwarden of Great Ryburgh church) Felix always preferred to travel by the easily navigable rivers of East Anglia (which are plentiful) and he is also closely linked with nature, especially such animals as beavers and badgers. In Suffolk St. Felix founded a monastery and numerous churches, concentrating his preaching in the areas where the unconverted people lived. Local folklore says that the saint himself taught the populace of Suffolk to build their churches of flint that lay in plenty in the county’s fields. The cathedral that Felix founded in Suffolk was the center of the East Anglian diocese until the 860s Viking invasions, though in 673 the holy Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury divided the diocese into two parts, adding the new see of Elmham. Subsequently the diocese of “Dommoc” ceased to exist and Elmham was replaced with the Diocese of Thetford and that, in its turn, with the famous Diocese of Norwich, which still exists.

Remarkably, the school that Felix founded in Suffolk greatly developed; not only future priests, but also ordinary people studied in it. Theology, the Holy Scriptures, the teachings of the Church Fathers, and the copying of manuscripts and Latin were taught there. Spiritually, it could be said that the school founded by Felix was the ancestor of Cambridge University.

Among other churches founded by Felix in Suffolk let us mention those at Hallowtree (the village no more exists) near Felixstowe; Beccles in the north; Flixton (probably meaning “Felix’s Town”) in the north, where the village sign still bears the holy bishop’s depiction; in the small town of Sudbury on the River Stour near the Suffolk-Essex border (presumably on the site of the present-day St. Gregory’s Church); and in Bury St. Edmunds (at that time called “Bedricsworth”) in western Suffolk, where Sts. Sigebert and Felix jointly founded a monastery. In fact Sigebert became its first monk but was martyred two years later. Unlike other early monasteries that later disappeared into oblivion, the monastery of Bedricsworth became one of the largest and most important in the history of England and the resting place for many centuries of St. Edmund, King of East Anglia and the first patron-saint of England. Thus the role and contribution of St. Felix to the English Church, history and education cannot be overestimated.

Felix’s apostolic labors extended north of Suffolk to the larger county of Norfolk, which is unique in many ways. Most strikingly, this county is estimated to have the highest concentration of medieval churches in the world! In the medieval period it boasted of over 1,000 churches, around 650 of which survive (some with recent modifications); and even more churches were opened after the Reformation in Norfolk, which today has no fewer than 910 churches in total. In addition, about 125 of the 185 churches with round towers in England can be found precisely in Norfolk.

The oldest Christian church of Norfolk is dedicated to St. Felix, its founder, though only ruins of it survive. It is situated in Babingley in the county’s north-west. The village itself disappeared long ago, while the place still has the presence of holiness. It was said that, as usual, Felix reached this area by sea and river and established a mission here among the locals that was very successful. According to one tradition, the saint after being consecrated in Canterbury made his landfall (or was even shipwrecked) at Babingley and not in Dunwich. True or not, but he certainly preached here along the Babingley River and the low hills nearby (though Norfolk is mostly a flat county) have been called the “Christian Hills” since ancient times.

A few miles downstream from Babingley sits the village of Flitcham, whose name may have been derived from the name of St. Felix and whose village sign commemorates the saint. The holy man certainly founded a church here and moved further to the north by river. He finally reached the settlement which today is called Shernborne. He stopped there and built the church in honor of the Apostles Peter and Paul (a common dedication of that era); and, miraculously, this church—the second oldest Christian church in Norfolk—survives in this hamlet to this day.

Interior of St. John the Baptist's Church in Reedham, Norfolk (photo kindly provided by the churchwarden of Reedham church)

Interior of St. John the Baptist's Church in Reedham, Norfolk (photo kindly provided by the churchwarden of Reedham church) Another St. Felix’s center of evangelism in Norfolk was concentrated in the county’s center. Here the village of Saham Toney, to the south of Swaffham on the River Wissey, has a link with our saint. But, most importantly, the very ancient church of the tiny village of Cockley Cley several miles away stands as a living memory of St. Felix’s labors. Although the area is now sparsely populated, in the Middle Ages it was one of the most densely populated areas in the east with numerous churches dating back to the earliest times. Two churches associated with Felix in this village survive—those of St. Mary the Virgin and All Saints. The saint either visited or built them. Finally, the illustrious bishop was active in the county’s south-east near Yarmouth and beside the River Yare. There the foundation of churches in Loddon and Reedham is attributed to him. It is noteworthy that Reedham was most probably one of the palaces of the kings of East Anglia. The memory of Felix is kept in all these places and is passed down from generation to generation.

As for county Cambridgeshire, the only place closely associated with St. Felix’s activities there is Soham near the Suffolk border. Its lands belonged to East Anglian kings and, according to a strong tradition supported by the majority of modern hagiologists, Felix founded a monastery with a seminary there. Some traditions credit Felix with the building of the first church in Ely in Cambridgeshire, where his spiritual daughter, St. Etheldreda, was destined to found a great monastery. Possibly this church was built earlier in that century by St. Augustine, but at least spiritually St. Felix contributed to the birth of that prominent monastic center as he preached in that region and nurtured Etheldreda spiritually.

Among other deeds performed by Felix let us mention baptizing King Cenwalh of Wessex (ruled 642-645 and 648-672) during the latter’s several years of exile in East Anglia after being banished from his kingdom by Penda. And, finally, it is most likely that St. Felix once travelled north to Yorkshire where he had a meeting with St. Aidan of Lindisfarne, the enlightener of Northumbria. We know from St. Bede that Aidan was held in veneration by St. Felix and other bishops from far afield (The History, Book III, ch. XXV). Though we do not know the exact reason for their meeting, but it may have taken place while Felix was on pilgrimage to Lindisfarne. Some claim that the saint had a meeting with St. Paulinus in York, which is less probable as Paulinus retired to Rochester in 633, soon after Felix’s arrival in East Anglia. Two villages in Yorkshire have parish churches dedicated to St. Felix in honor of that meeting: the first one stands in Felixkirk (“Felix’s church”) near Thirsk in North Yorkshire (extensively rebuilt in the 1860s), the other stands at Kirby Hill near Ravensworth in the same county and shares the dedication with St. Peter.

St. Felix reposed in the Lord on March 8/21, 647 (648 according to another version) and was buried in Dunwich. His successor as Bishop of East Anglia was his disciple Thomas. His veneration as a saint began immediately. Soon afterwards his relics were translated and enshrined in Soham, where they were venerated until the 869 Danish raid. Then his holy body disappeared and was deemed lost until it was miraculously rediscovered in the early eleventh century during the revival of monasticism in England. From the 1020s till the bloody Reformation, Felix’s relics were kept at the Monastery of Ramsey in Cambridgeshire. The translation was carried out on the orders of King Canute and, according to legend, while the monks were on their journey with the relics, a band of monks of Ely attempted to pursue them and seize the body, but at that time dense fog descended and the “dishonest” monks lost their way. During the dissolution of the monasteries in the sixteenth century the relics disappeared forever—they were either destroyed or buried secretly on the abbey’s territory.

Yet these are not all the relics of our saint. There existed an early manuscript, known as “the Red Book of Eye”. The tradition holds that it was the personal Gospel book of St. Felix. This red copy of Gospel, written in Lombardic script, was transferred from Dunwich to the small town of Eye in Suffolk which had a priory and even survived the Reformation. It was used for taking an oath by the Corporation of Eye. However, the unique manuscript mysteriously vanished in the early nineteenth century and has not been seen since. Six early English churches were dedicated to our saint. And now let us talk about the veneration of St. Felix today.

Pilgrimages to Dunwich were resumed by Roman Catholics in 1927 and pilgrimages of Orthodox believers have been held since the 1990s. Eight churches on the site along with its cathedral were washed away by the waves of the sea, fell from the cliffs due to erosion or left derelict due to the shrinking population of the town. The last of these churches, All Saints, was abandoned in about 1750 and it entirely disappeared in the twentieth century. Some church memorials were saved and transferred to the present St. James’ Church that was built in the nineteenth century. The Black Friars, or Dominicans, had their monastery in the southeast of the town, but it was engulfed by the sea in the fourteenth century. Then the Grey Friars, or Franciscans, came here in 1250 and founded a monastery near the harbor, but after a massive storm they rebuilt their priory further inland in 1290. Of all the medieval shrines of Dunwich only ruins of this monastery still remain, namely a part of its refectory, or the south wing. The site is now protected by the Dunwich Grey Friars Trust.

Ruins of the Grey Friars Monastery in Dunwich, Suffolk (photo by Richard Croft from Geograph.org.uk)

Ruins of the Grey Friars Monastery in Dunwich, Suffolk (photo by Richard Croft from Geograph.org.uk) The original church was huge; nave and chancel together were some 190 feet long and up to fifty-five feet wide. Besides, Dunwich has a very interesting museum which displays the history of the town, with many archeological finds, maps, scripts, illustrations, a model of the ancient town, and a film dedicated to the site. Among items of particular interest are medieval pilgrims’ badges and jewelry. Among other minor ruins of Dunwich we can mention remains of the leper chapel along with several gates and sections of wall. According to local legend, on calm nights one can still hear the tolling of the bells of the long gone St. Felix’s cathedral and other sunken churches, buried beneath the waves of the sea but not erased from the spiritual history of this holy place. They are calling people to prayer.

The apostle of East Anglia is naturally remembered in Felixstowe. A Roman Catholic church built in this town just over 100 years ago is dedicated to St. Felix. The Victorian-era Church of St. John the Baptist in this town, constructed by Sir Arthur Blomfield, has a charming set of stained glass windows, depicting Sts. Felix, Edmund, Fursey, Etheldreda, Bede, and Hilda. The historic Church of Sts. Peter and Paul in Old Felixstowe, mentioned above, houses, among other treasures, stained glass windows depicting Sts. Felix, Edmund, Fursey and Sigebert. Like other prominent East Anglian saints, St. Felix’s images can be found in stained glass, sculpture, carvings and paintings in a host of churches of the region. One of the most striking examples is a depiction of this saint alongside many other holy men and women on a panel of the “Think and Thank Screen” of the fine St. Andrew’s Church in Great Ryburgh, Norfolk (the screen commemorates First World War victims).

The now abandoned village of Babingley (Norfolk) lies near the larger village of Castle Rising and consists of just a cluster of cottages. This earliest church of Norfolk, built by Felix about 1,400 years ago, lies in ruins in a remote area, surrounded by fields, on a farm. The original church was rebuilt in the fourteenth century but increasingly decayed from the 1600s, so it was decided to abandon it in 1880. Only the tower and the roofless shell of the former nave and south aisle now stand amid nature, ivy-grown, giving an idyllic yet melancholic picture. However, pilgrimages are arranged to this St. Felix’s ruined church, including those of Orthodox believers. It stands on the area belonging to the royal Sandringham Estate and is a scheduled monument. The village sign still commemorates the local legend of Felix and a beaver. A new mission Church of Sts. Mary and Felix was built a little way from this shrine over 100 years ago.

The tiny quiet village of Cockley Cley sits near the small River Gadder. This spot boasted of having three ancient churches. One of them disappeared 250 years ago. The second one, All Saints, dates back to the eleventh century, but it was substantially restored in the 1860s to 1880s. This gem had a beautiful round tower, but unfortunately it collapsed in 1991. The original of this church, perhaps built by St. Felix, has been under the patronage of the Roberts family of Cockley Cley Hall. The original of the third church, St. Mary’s, may date back to the 630s or 640s when Felix visited it. The church once prospered in this formerly rich agricultural region, but was declared redundant after the Reformation and was used as a cottage for centuries. It was due to the efforts of a local landowner, Sir Peter Roberts (1912-1985), that this church (the existing structure dates back to about 1100) was saved from demolition and restored as a chapel and a museum. Unfortunately, the museum was closed in 2016 and the building is now inaccessible to the public.

The tiny and half-abandoned village of Shernborne, today lying on the Sandringham Estate, has a church that is claimed to be the second oldest Christian temple in Norfolk, built by Felix. The ancient church was largely rebuilt at the end of the nineteenth century by the then Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, to save it from decay. One of the finest features saved from the original church is the 1,000-year-old splendid Norman font. The Church’s patrons, Sts. Peter and Paul, are depicted on stained glass.

St. Mary's Church in Flitcham, Norfolk (used with the kind permission of the rector of the local benefice)

St. Mary's Church in Flitcham, Norfolk (used with the kind permission of the rector of the local benefice) The peaceful village of Flitcham is located on the edge of the mentioned royal estate. Remarkably, it was here that Olav V, future king of Norway (ruled 1957-1991), was born in 1903—his mother was Princess Maud, daughter of Edward VII. The archeological excavations revealed traces of Roman occupation and Anglo-Saxon activity (pottery, metalwork) on this site. It was the home of one of St. Felix’s fruitful missions. The large St. Mary’s Church was built on the site of the original church in the 1100s. Unfortunately, very little remains of this cruciform Norman church. Its huge chancel and transepts are nearly completely gone, the present quiet and pretty chancel is under the Norman tower, and all the rest is a later rebuilding, sponsored by the Royal Family. It is still dedicated to the Holy Virgin.

The south side and porch of the Holy Trinity Church at Loddon, Norfolk (photo kindly provided by rector of the Loddon church)

The south side and porch of the Holy Trinity Church at Loddon, Norfolk (photo kindly provided by rector of the Loddon church) The little town of Loddon can be found in the south of Norfolk. Felix founded a church in Loddon in the seventh century, but sadly the church that he built was dismantled and a new one was built on the site by Sir James Hobart in about 1496 that is dedicated to the Holy Trinity. The site of the church chosen by Felix overlooks the River Chet, a tributary of the River Yare. The present large church has a medieval “statue of the Holy Trinity” above the south entrance door that was accidentally discovered during nineteenth-century repairs; a fifteenth-century “seven-sacraments font”—a common feature of medieval Catholic England—with panels which, alas, were heavily defaced by the iconoclasts; and the partly surviving sixteenth-century “rood screen” with panels depicting scenes from the New Testament and a couple of saints. Notably, despite the era of Puritan iconoclasts, some fascinating early rood and altar screens, depicting early local saints, by miracle survive in this county’s churches.

Exterior of the John the Baptist's Church in Reedham, Norfolk (photo kindly provided by the churchwarden of Reedham church)

Exterior of the John the Baptist's Church in Reedham, Norfolk (photo kindly provided by the churchwarden of Reedham church) The large Norfolk village of Reedham is situated between Norwich and Yarmouth, it is surrounded by marshland. Extensive archeological excavations over the years revealed numerous Roman and possibly Saxon fabric in this village (including those used for the rebuilding of the temple). The Church of St. John the Baptist was built by St. Felix, making it one of the earliest Christian sites of the county. The church was enlarged in the thirteenth century and contained many treasures. Unfortunately, most was destroyed by fire in 1981, leaving the church an empty shell with its tower. The temple was quickly rebuilt by the friendly community and services resumed in 1982. The current church is large and it uniquely has two arches under one roof. Its north wall is the oldest (the eleventh century), and a part of the wall is exposed, revealing the “herring bone” pattern of using of Roman tiles. The temple comprises some Roman stone and brickwork.

Latest excavations next to the Reedham church of St. John the Baptist, Norfolk (photo kindly provided by the churchwarden of Reedham church)

Latest excavations next to the Reedham church of St. John the Baptist, Norfolk (photo kindly provided by the churchwarden of Reedham church) St. Felix is featured in the church’s displays, and the community commemorates its patron, St. John the Baptist, on his Nativity day. The window glass in the main East window shows John Baptist (blue) meeting Christ (gold), and the Chapel window on the right is of the Cross—this chapel-aisle is dedicated to St. Helen, but is usually known as the Berney Chapel, from the family whose memorials it contains. Since recently a team of Reading University has been carrying out new excavations around the church, hoping to find evidence of a large Roman structure or even a Saxon church. If it does happen (the results are to be published by the university later), then the truth of early traditions connected with another early English saint will be proven!

The little town of Soham in Cambridgeshire claims to be the earliest Christian site in this county. The monastery founded here by Felix flourished for 200 years but was never revived after the Viking invasion. A late Saxon church or cathedral was constructed on the same spot which was rebuilt in the twelfth century and dedicated to the Apostle Andrew. This church stands to this day and is called “Soham Abbey”, though it is a Church of England parish church. The temple retains some minor masonry from the Saxon period. Its main relic is a life-size stained glass commemorating St. Felix that was solemnly installed in 2002 with hundreds of worshippers attending the ceremony. On it Felix is depicted with many symbols of his ministry and achievements: the arms of Cambridge University, the foundation of the monastery, the rock on which the saint founded Dunwich Cathedral, the Tree of Knowledge, and the present church (St. Sigebert can be seen in one of the scenes). St. Andrew’s also has a wall painting presumably depicting Felix.

St. Felix Window inside St. Andrew's Church in Soham, Cambs (photo kindly provided by the Soham church)

St. Felix Window inside St. Andrew's Church in Soham, Cambs (photo kindly provided by the Soham church) The small town of Ramsey in Cambridgeshire is the place where St. Oswald of Worcester founded a huge monastery, initially surrounded by the fens. The monastery collected numerous relics, including those of St. Felix and the martyred brothers Ethelbert and Ethelred of Kent. The church that today dominates the town’s center is dedicated to Thomas a Becket. It was built about 1180 perhaps as the monastery’s hospital and later remodeled as a church for the townsfolk, which saved it from demolition at the Reformation. The ruins of the monastery are in private ownership, though its former gatehouse can be visited. Inside St. Thomas’ Church pilgrims can see a contemporary stained glass depicting Sts. Felix, Etheldreda and Thomas a Becket.

* * *

Until recently “Felix” was among the popular boy’s baptismal names in East Anglia, and this continues occasionally. The veneration of St. Felix among Orthodox continues, with an Orthodox service to this saint compiled. This celebrated man of God, who most successfully combined preaching, education and Church administration, baptizing East Anglia, is calling all of us to return to our Orthodox Christian roots.

Holy Father Felix, pray to God for us!

Several facts mentioned in this article were taken from the booklet by Fr. Andrew Phillips, called The Story of St. Felix, Apostle of East Anglia, published by The English Orthodox Trust in Felixstowe in 2000, with the author’s permission.