The main theological dispute in sixth and seventh-century Ireland was the controversy over the correct date for Pascha. The point is that from the time of St. Patrick (c. 390 – c. 461 or 492?) the Celtic Churches of Ireland, Britain (especially of Wales) and among the British emigrants to mainland Armorica (now Brittany) used the paschalia based on the eighty-four-year cycle, which meant that Easter could fall at the earliest on the fourteenth day of Nisan and at the latest on the twentieth day of Nisan (according to the lunar calendar), or, in other words, between March 25 and April 21 (according to the solar Julian calendar). This method of calculating the day of the Resurrection of Christ was different from those of Rome and Alexandria; according to the latter, the Christian Pascha could never fall prior to the Jewish Passover, while the former ignored this precaution. The Irish tried to prove the correctness of their paschalia by making references to the apocryphal acts of the Council of Caesaria and a treatise on time of the Paschal celebrations, attributed to St. Anatolius of Laodicea.

St. Augustine of Canterbury, who between 597 and 604 served as a missionary among the Angles and Saxons who had invaded parts of Britain, drew the attention of the Holy See to the errors in the Celtic paschalia that he deemed unacceptable. Thenceforth the popes of Rome while maintaining contacts with the hierarchy of the Irish Church insisted that the Church in Ireland adopt the Roman paschalia. In 628, Pope Honorius I (who favored the heresy of Monothelitism and was eventually anathematized for this at the Sixth Ecumenical Council) addressed his message to the Irish hierarchs in which he demanded that they adjust the local Church traditions to the Roman practices and adopt the computes (the calculation for the dates of Easter), compiled by Dionisius Exiguus († c. 550). According to Venerable Bede, “Honorius wrote to the Scots [the Irish], whom he had found to err in the observance of the holy Festival of Easter…, with subtlety of argument exhorting them not to think themselves, few as they were, and placed in the utmost borders of the earth, wiser than all the ancient and modern Churches of Christ, throughout the world; and not to celebrate a different Easter, contrary to the Paschal calculation and the decrees of all the bishops upon earth sitting in synod.”1

In about 630, a Church Synod was held in Old Leighlin, or Magh Lene which sent a delegation to Rome to discuss the paschalia. After that a number of bishops, monasteries and parishes of Ireland adopted the Roman paschalia, whereas other communities rejected it, choosing to stick to their national tradition. Among the proponents of the Irish tradition was the community of the most celebrated and influential monastery in the Celtic world, namely Iona in Scotland. Defending it, Abbot Segene of Iona (623-652) referred to the precepts of the Venerable Columba, the monastery’s founder. In 632, St. Cummian, abbot of another monastery, situated in Dermagh (now Durrow, Ireland), in his letter addressed to the fellow-abbot Segene and the holy hermit Beccan called upon them to adopt the Roman method of calculating Easter for the sake of Church unity and peace. He further said with irony, “Can anything be more absurd than to say… Rome errs, Jerusalem errs, Antioch errs, and the whole world errs, the Irish and the Britons alone are in the right?”2

Right after his election to the Papal Chair, John IV sent an epistle to Ireland, “To our most beloved and most holy Tomianus, Columbanus, Cromanus, Dinnaus, and Baithanus, bishops; to Cromanus, Ernianus, Laistranus, Scellanus, and Segenus, priests; to Saranus and the rest of the Scottish doctors and abbots… We have found that some in your province, endeavoring to revive a new heresy out of an old one, contrary to the orthodox faith, do through the darkness of their minds reject our Easter, when Christ was sacrificed; and contend that the same should be kept with the Hebrews on the fourteenth of the moon.”3 We well recognize this imperious tone and didactical manner of speaking of the Roman See’s officials that had become common from the time of Pope Gelasius I. The disinclination to adopt the Roman paschalia was plainly and rigorously branded as a “heresy” in this message, coupled with another grave accusation of the heresy of Pelagianism, which, however, had been totally eliminated in both Britain and Ireland very long before. “And we have also learnt that the poison of the Pelagian heresy again springs up among you; we, therefore, exhort you, that you put away from your thoughts all such venomous and superstitious wickedness. For you cannot be ignorant how that execrable heresy has been condemned; for it has not only been abolished these two hundred years, but it is also daily condemned by us and buried under our perpetual ban…”4 Although today this tirade may sound too emotional, the papal letter proceeded to rightly expose the fallacy of Pelagius’ teaching. But indeed these accusations “missed the mark” and were 200 years late: “Who would not detest that insolent and impious assertion, ‘That man can live without sin of his own free will, and not through the grace of God?’… And it is blasphemous folly to say that man is without sin, which none can be, but only the one Mediator between God and men, the Man Christ Jesus, Who was conceived and born without sin; for all other men, being born in original sin, are known to bear the mark of Adam’s transgression, even whilst they are without actual sin, according to the saying of the prophet, ‘For behold, I was conceived in iniquity; and in sin did my mother give birth to me’.”5 That is an excellent argument against the false teaching of the “Immaculate Conception”, of the Virgin Mary, proclaimed by Pope Pius IX a dogma of the Catholic Church. By the way, this concern of the Roman Church over the seeming rebirth of Pelagianism in Ireland indirectly indicated that the soteriology of its (Irish) theologians was closely connected with the teaching of St. John Cassian, which was accepted by Eastern Christianity and rejected by Western Christianity as semi-Pelagianism.

John IV’s admonition had only a limited success. Anyway Iona Monastery didn’t change its customs of calculating Easter at that stage.

At the close of the seventh century, at the Synod of Birr (Ireland) in 697 the Holy Abbot Adomnan of Iona insisted on the adoption of the Roman paschalia in the churches of Ulaid (a Gaelic kingdom in the north-eastern Ireland). At that time most of Western Europe observed the Roman practice of calculating Easter, yet his own Iona Monastery’s brethren did not change their minds and continued to uphold the Celtic customs. St. Adomnan reposed in the Lord in 704 or 705 at the great age of eighty. According to his life, “Unfortunately, Adomnan did not live to see the moment when Iona accepted the Roman method of calculating Easter—this happened in 716.”6 At the mentioned Synod of Birr, St. Adomnan’s “Law of the Innocents”, also known as “Cáin Adomnáin” (“Law of Adomnan”), was adopted with the full support of Loingsech mac Oengusso, king of Ulaid. By this law the saint secured the exemption of clergy, women and children from compulsory military service. It also prohibited use of violence towards unarmed people during hostilities.

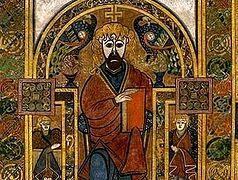

The Monastery of Iona, which was situated on a tiny island in what is now Scotland, was the most influential spiritual center for Ireland. Men of prayer and ascetics, preachers and missionaries, scientists and theologians, scribes and copyists of manuscripts written in Gaelic and Latin lived in it; skillful masters—wood and stone carvers along with metal crafters made crosses, chalices, and patens; talented artists illuminated manuscripts with wonderful, colorful miniatures. Young people from across Ireland, Scotland, Wales, early English and Saxon kingdoms and the continent would sail to the school of Iona for spiritual education, experience in prayer and ascetic life. On receiving monastic tonsure they would stay in Iona Monastery, or return to their native lands, or travel to foreign lands to bring the light of Christ’s Truth to their peoples. The reputation of Iona Monastery was such that as long as it adhered to its national customs as to the calculation of Easter, many monasteries and parishes of Ireland upheld them. And as soon as Iona adopted the Roman paschalia, it was followed by other churches of Ireland, Scotland and Wales that had refused to do it before.

Monks of Iona and other Irish monasteries of Ireland and Scotland labored as missionaries far beyond their own countries and the neighboring Britain. According to the French medievalist Jacques Le Goff (1924-2014), “Over the sixth and seventh centuries Ireland ‘exported’ about 115 holy men to Germany, forty-five to France, forty-four to England, thirty-six to the territory of what is now Belgium, twenty-five to Scotland, and thirteen to Italy.”7

The monastic rule of the Venerable Columbanus (c. 543 – c. 615) that was adopted by the monasteries founded by him and his disciples in mainland Europe rivalled that of St. Benedict of Nursia. In J. Le Goff’s view, “The moderateness of the rule of St. Benedict was in some sense alien to the Irish monasticism… True, prayer, manual labor, and study were the basis of the rule of St. Columbanus; but, apart from all this, it required extremely strict fasting and austere ascetic life. The practice of reciting prayers in a standing position with arms crossed for many hours in succession staggered contemporaries. For example, St. Kevin of Glendalough was said to pray thus, leaning against a board, for seven years running. Over that time he did not make a single movement and closed his eyes neither day nor night, so even birds built their nest on him.”8 A legend or not, this peculiar feature is surely so typical for the religious mentality of that epoch and that nation. We can draw a parallel between this kind of spiritual labor and the stylitism (pillar asceticism) of monks of Eastern Christianity, of the Russian St. Nilus of Stolobny Island [on Lake Seliger in the Tver region north of Moscow]. Therefore, there are many similarities between the ascetic traditions of early Irish saints (though they may seem a little “eccentric”) and the monastic practices of the Eastern Church.