Changes in a nation’s political climate inevitably entail changes in its political language and thought. During the 20th century, Russia twice experienced profound changes in its political language—once after the revolution of 1917 and once again during the perestroika period with its “New Political Thinking.” On both occasions, new names for cities and streets as well as new forms of personal address were introduced. Attitudes toward historical figures changed, as did the names of the most important state institutions. We even came up with new words to name the people who inhabit our nation. A new language meant a new world view, new values and a new identity.

After perestroika and its attendant reforms, Russia adopted a liberal political language, in other words, the language of modern Western culture and international communications. Russia learned the lingo, and yet, unlike the Western world, Russia never actually put it to use. Before that happened, the postmodern crisis of culture—and the breakdown of the unipolar era of international relations—had already made clear the need to develop a new paradigm and a new language capable of adequately describing the modern world. The liberal take on freedom, human rights, multiculturalism, democratic values, civil society—concepts that only yesterday had seemed basic and self-evident—suddenly lost their internal coherence. A mere ten years after perestroika, both people and national authorities suddenly found themselves at a loss for words. The old language no longer sufficed for either domestic or international use.

It was at this point that Russians started offering the outside world a new political language. The repeated message of Russian leaders in various international venues was that the world is changing rapidly, and that the old paradigms of thinking are causing distortions and misunderstandings and giving rise to new crises. More recently, Russia’s political classes and intellectual elite have come to the conclusion that, before trying to export its language on the international stage, Russia still has work to do clarifying our own conceptual apparatus, our own values and identity.

In his speech at the Valdai Club in 2013, Vladimir Putin made clear that the strengthening of the Russian state in the foreign policy arena was being hampered by the amorphous quality of Russian society, its values and tasks. As a result, one of the key questions for modern Russia, he said, is the question of “who are we?” There is, to be sure, something tragic about having to raise such a question in a country with a many centuries-old history—all the more so, given that the people of Russia indeed have a sense of their own identity. And yet they have no durable name.

We call ourselves “Rossiyane” [untranslatable—“Russian nationals” is an approximation; cf. Russkyi, which means “Russian”], a multinational and multi-confessional people. We are addressed as “citizens of Russia,” an alliance of fraternal peoples. Recently, in order to distance ourselves from such bland expressions, we have taken to saying “we are Russia” or “we are the Russian world” or “we are the Russian civilization.” It has come about, then, that we understand ourselves more clearly in a geo-political context than we do in a simply national and internal context. The country’s name sounds to us more concrete and meaningful than does the name of its people.

Our self-definition as a people has been further complicated against a background of the strengthening of the country's constituent national minorities. The parade of varied identities existing in the national republics, something which began in the 1990s, has now reached a zenith. While Russia, after the collapse of the USSR, was busily entering the system of Western globalization, its internal national regions were finding for themselves a foothold in a rapid localist nationalism. Russia has experienced what is now fashionable to call glocalization—the simultaneous process of globalization and localization, the decomposition of the state as subject by nationalism and globalism.

Modern globalization encourages local patriotism more than it does a patriotism oriented to the state. Being a patriot of a separate subject within a federation, or of a separate Russian city, is more prestigious within the global and liberal paradigm than, say, being a patriot of the Russian world. Patriotism on the scale of a large-scale political formation, by contrast, is considered by modern discourse as equivalent to indulging in ‘imperial ambitions.’ The development of this trend encourages ethnic isolationism and regionalism, the artificial construction of new regional identities (new Siberians, Kaliningradians, Pomors, Ingermanlanders and others).

All of which gives rise to a quest for integrating meanings and names. The idea of Russia as a country-civilization is now seen by many as attractive. It brings to mind the image of a unified poly-ethnic and multi-confessional state, the foundational elements of which remain Russian culture and traditional Christian values. This idea of civilization responds to a political imperative. It allows us to talk about the general while avoiding particulars, and it allows us to effectively develop an external doctrine while postponing the development of an internal one.

However, the balance between modern Russia’s external and internal (national) identities is fragile. Russia’s image as a participant in international relations is unquestionably something bright and content-rich. We know full well who we are in the world and what our international interests are. The international community likewise immediately understands who and what is being talked about whenever the subject of Russia comes up, because for them we have always remained “Russians”—under the tsars, under the Soviets, and under liberalism. The local, ethno-regional identity of the Russian national republics is also something clear and understandable. However, the nationwide, consolidated identity is still perceived by the inhabitants of the country vaguely. It doesn’t keep up with the dynamics of our international and internal regionalist processes. The people of Russia has the quality of being a big abstraction, something contingent and lacking a concrete structure. This situation is captured by the term Rossiyane (“Russian nationals”), which has a broad, geographical ring to it, as opposed to something to do with values, or something specific. As “Russian nationals” we are not able to connect the global identity of Russia with the ethnic identities developing in the Russian regions; the term does not serve therefore as a mechanism for the cultural and historical assembly of the entirety of the people. It turns out that there is an identity here, but we have no effective working term for it. So it happens that these strange questions arise, posed by a state with a thousand-year history.

***

It came to pass that, when the Soviet period ended, the use of the term “Russians” became a symbol of ideological power. Only those in a position to dominate the formation of public opinion were able to use this word without danger; as a result, initially it was precisely a liberal discourse that held the monopoly on use of the word. Later, however, new centers of power started emerging—political parties, the army, the Church, new political leadership, etc.—that had their own independent influence on the information agenda. This is why the term “Russians” gradually began to take on differing emotional interpretations, and this in turn had to two consequences: first, the word Russian stopped being tabooed; and secondly, a struggle began between its varying interpretations.

Liberal Democrats

As noted above, the liberals who came to power in the new Russia remained for a long time the only force that had the right to use the word “Russian.” At that time, a kind of norm was established that “Russian” can only be used as a name for what has either an anti-Soviet overtone (“The Russian Liberation Army,” “Russian Thought,” “the Russian Service of the BBC”), or else to refer to what is “new Russian”—that is to say, what is non-national and not connected with the historical Russian people (“Russian Radio,” “Russian Journal”).

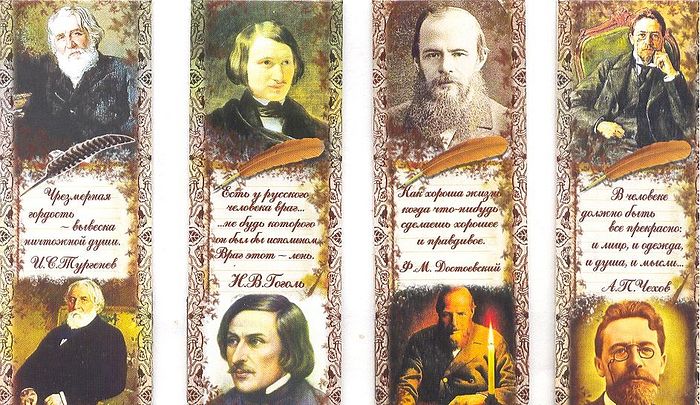

The term “Russian national” [in Russian, the single word rossiyane (noun form) and rossiskii (adjectival form)—Trans.] at that time was assigned a semi-official role. In this word there was nothing intellectual, ideological or colorful—as the examples of “Rossiyskaya Gazeta (Russian National Newspaper),” “Russian national society,” and “Russian national authorities” make clear. Music, history and the army also came to be exclusively designated as “Russian national” [rossiskii]. The only thing that could not be so renamed was Russian literature. On the one hand, the introduction of the idea of “Russian national [rossiskii] literature” would have meant a considerable stylistic strengthening of the word. It would lend it substance and deprive it of its neutral-semi-official connotation. It would be even more difficult to simultaneously designate as ‘Russian national’ writers at once Pushkin, Dostoevsky, Bulgakov and Nabokov. On the other hand, our contemporary writers want to feel that they are Russian writers, and refer to themselves as such: i.e., they are Russian (Russkie), and not ‘Russian national’ (Rossiskie) writers. The goal here is to be to be associated with the classics of 19th century Russian literature, not Russia as a geographic location. By calling themselves “Russian writers” they put themselves in the same lineup as classics like Tolstoy or Chekhov. Russian (not ‘Russian national’) literature, just like ‘Russian ballet,’ is a well-known international brand. Having the status of a ‘Russian writer’ gave the intelligentsia an additional opportunity for socialization within modern Western cultural and information spaces. To be aware of oneself as a Russian writer is still pleasant whether one is in London or in Zurich.

Liberal Nationalists

At that same time, back in the 1990s, an unusual ideological hybrid appeared in Russia, one combining liberalism with Russian nationalism. The idea for this hybrid was borrowed in part from European national-democratic and national-liberal parties, but in part it was something newly invented.

Our Liberal Nationalists came into being operating either beyond the bounds, or just on the edge, of permissible political discourse; they are often marginal actors—and, it should be noted, this is a conscious strategy with them. They exist as a branch of Russia’s liberal democrats, and their role is to carnivalize and marginalize the theme of Russianness, empty it of independence lest it become a consolidating force. They deprive the term “Russian” of axiological-historical content, filling it instead with a nationalistic meaning (Zhirinovsky, Krylov, Prosvirnin).

The Liberal Nationalists create in the public sphere a degree of Russian nationalism that is at once artificial and controlled. On the one hand, the “Russian threat” legitimizes the liberal democrats and contributes to the strengthening of the myth that they are the only civilized force protecting society from nationalist chaos. On the other hand, liberal nationalists haven’t surrendered the Russian theme as a political asset. They turn Russians into an oppressed minority and then use this image in order to drive Russians into a psychological ghetto (“we are for the poor, we are for the Russians”), which is a very useful strategy for them, given that the idea of the minority is the technological driver of the modern protest movement (Belkovsky, Navalny, the National-Democratic Alliance). A political El Dorado awaits them if they should ever succeed: if you can turn the majority into a “minority” it will become the most powerful minority in the country—one with sufficient strength to seize political power in the country.

In short, the liberal nationalists paint the term “Russians” in nationalistic tones, depriving the word of any content that could have cultural significance for the whole, while also making use of it to define a protest-minded political minority.

The New Modernists

The liberal approach is built on postmodern principles and paints the term Russians [Russkie] in contradictory tones. Russian came to mean at one and the same time “anti-Soviet” and “dark nationalism” and “oppressed minority”. The attempt to resist this modality led to the revival and strengthening of the modernist approach in Russian discourse. The worldview of the modern and all the various derivative modernist currents arose and, for a long time, continued existing precisely as a means of denying, or at the very least radically reinterpreting, Tradition. However, under contemporary conditions, a modernism which has given way to the postmodern era now seeks for itself a niche among the classics; it wishes to become a new tradition, that of the main antithesis to postmodernity. Modern modernism tries to imbue the term “Russians” with the spirit of Soviet patriotism, nationalism and mild atheism.

Russian modernists (Zyuganov, Kurginyan, Prokhanov) use the word Russian as a particular manifestation of the “Soviet” construct, so as to build a new “Russian-Soviet” people. It is from this modest beginning that all the stylistic features of this approach originate. Among today’s modernists, the Russian people appear as, undoubtedly, an imperial people (though in the Soviet sense); not necessarily Orthodox Christian but respecting Orthodoxy; hopelessly nostalgic for Soviet achievements; as striving more for technical than for humanitarian development, and, finally, as striving for historical revenge for their defeat in the Cold War. The image of Russians for modern political modernism consists, most often, of a simple working people lacking in clearly expressed national characteristics, but who are striving for the restoration of the USSR or of a similar super-state. This modernist perspective views Russian culture more as a strategic element useful for the preservation of statehood than as something valuable in its own right.

Our contemporary modernists use the concept “Russians” as a simple unchanging unity, as an obligatory detail in the overall framework of the state. The defining characteristic of this view is its utter lack of psychologism. For the modernist there exist no questions of the sort raised by Dostoevsky about the nature of the Russian soul, nor any of the metahistorical reflections of Solovyov about the Russian idea.

Russians Abroad

The word “Russians” took on a particular resonance under the influence of the theme “Russians abroad,” a theme which rang out from the very beginning of the perestroika period. It united the interest of Russian society of that period in the life and work of the Russian emigration, of pre-revolutionary Russia and also the lost culture of the Russian nobility. A strong impetus for the awakening of this interest was the mass publication in Russia, during the 1990s, of scholarly works and memoirs of emigrant authors. Soon after Solzhenitsyn’s return, the Solzhenitsyn Centre for Russian Emigré Studies was opened in Moscow, which took on the task of preserving and popularizing the “spiritual and material culture of the Russian emigration.” The modern community of émigré Russians1 does not use the term “Russian nationals” [Rossiyane], they use only the word “Russian”—e.g., “Russian emigration,” “Russian America,” “Russian history,” the “Russian way,” “Russian world,” etc.

In the language of the emigré world, the word “Russians” is associated with the highest and most educated class, those who were the custodians of the high traditions of a Russia that had been lost. It is associated as well with rejection of Bolshevism and of Soviet stylistics generally. The image of the Civil War looms larger, in their understanding of this word, than any other historical event. What is more, many émigré Russians belonged to the nobility, and so the self-referential word Russians acquired for them an additional connotation of high rank, something connected with their former greatness.

An integral semantic element of this take on the word “Russians” is Orthodox Christianity, which, along with the Russian language itself, became the most important attribute of the Russian emigre world’s self-identity. Orthodoxy played an important ideological role (e.g. condemning the persecution of the Church by Soviet authorities), but it was equally important as symbol—for example, the Orthodox ritual and the Old Church Slavonic language served to reconstitute the image of pre-revolutionary Russia. Russian communities abroad lived with the feeling that they are the guardians of the historical Russian faith and are its last bearers. Even though generations of Russian émigrés were physically, intellectually and spiritually plunged into another reality, though they served in the armies of other nations, became patriots of their new countries and gradually forgot the Russian language, it was their attachment to their Orthodox Christian roots that, most often, allowed them to still consider themselves Russians.

The tonalities of the Russian diaspora turned out to be both fresh and in demand for post-Soviet Russia. It became almost the only acceptable means of expressing nostalgia for tsarist times. Later, in the 2000s, when it softened its natural anti-Bolshevism, émigré culture was adopted by theorists of the concept of the Russian world, including by Russian historians and public figures associated with that movement (the Foundation for Historical Perspective, the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation, the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, the Russkiy Mir Foundation and others) .

Neopaganism

Nationalist movements in the new Russia have had a strong stylistic influence on the resonance of the word “Russians” in the contemporary context. Despite the diversity of such organizations (which include participants of the “Russian March,” the National Bolshevik Party, neo-Nazi groups) and the marked diversity of their ideologies (imperial, Hitlerite, international, Slavic neo-Nazi, etc.), the tonality of their perception of Russianness is reducible to a single note—one that is primitive and pagan. It includes both a pronounced dislike for inhabitants of other tribes and a conviction of their own genetic superiority. At its core, this view is based on blood mysticism and the language of biology. Mysticism fills the nationalist movement with emotional energy, while biology serves as the rational underpinning for the construction and maintenance of its teachings. This ideological trend is oriented in particular toward the lumpen proletariat, for whom such primitiveness works well. Any attempts to complicate this pagan-biological understanding of the word “Russians” lead to the rapid disintegration of the nationalist movements’ ideological underpinnings. Orthodoxy, Russian history, literature and philosophy are insignificant factors in the teachings of these organizations, since they do not play a decisive role in the preservation of the biological species. Sometimes these areas are, indeed, directly declared ideologically hostile, but when they are accorded any recognition at all, they are used purely formally, in isolation from their Christian ethical and moral content, so as to thereby form a neo-pagan Russian style.

Those closest to this approach are the liberal nationalists. Neopagans, like the liberal nationalists, depict the Russian majority as an “oppressed minority” and both are similarly opposed to the state authorities, accusing them of incompetently implementing national policy. The main difference between them is that the neo-pagans insert into the word “Russian” a non-Christian mystical spirit. Stylistic mysticism stains the neo-pagan nationalists (of both right and left) and darkens their use of the word “Russians”, whereas liberal nationalists remain within the secular, liberal paradigm and are seldom addicted to pagan mysticism. Nevertheless, because of the ideological proximity of these two camps, it can be difficult to draw a perfectly clear demarcation line between them.

Antiglobalists

Russian national anti-globalization movements are peculiar, poorly developed, and only remotely resemble their Western counterparts. Like many of their western counterparts, their rhetoric is aimed at criticizing transnational corporations, the misbalance in the global distribution of wealth (as in the theory of the golden billion, influenced by the Club of Rome's “Limits to Growth”), modern mass culture, and the principles of global capitalism and the ideology of neoliberalism. A distinctive feature of our domestic anti-globalists is their widespread use of Orthodox and patriotic stylistics (“The Russian Folk Line,” “Arise for your faith, Russian land,” “The Union of Orthodox Banner-holders,” opponents of INN [individual taxpayer number], some small Orthodox sects etc.). They make active use of the word “Russian” and imbue it with their special outlook. Their perception of the modern historical process is sharply eschatological. They view the world as an aggressively hostile environment and this leads them to adopt a defensive ideology, one that views Russia as a surrounded fortress: an island of good in a world of ever-expanding globalization. This encourages the anti-globalists to develop a conspiratorial style of thinking and a mood of both impending doom and chosenness. The former lends such movements their usual depressive emotional state, while the latter allows participants to enjoy a sense of their own uniqueness and their ability to rise above the contingently historical. All this has an impact on the semantic content of the word “Russians” for them: in the antiglobalist dictionary, the Russians are victims of deception and a secret conspiracy organized by world elites. They are a chosen people, one that preserves truth in the world and becomes for this very reason the main target of global evil, which will eventually lead to the Russians’ downfall. A Russian is someone doomed to destruction.

Our domestic anti-globalist's conspirological way of thinking pushes them into a constant search for the secret motives and designs behind global socio-political events. Having discovered the “hidden meanings” of those events, they devise on that basis general theories and their own view of the world. Their approach has a tendency toward esotericism (Orthodox opponents of the INN [individual taxpayer number] are often accused of constructing their own esoteric teachings). This esotericism stems not only from a propensity to mysticism, but also from purely analytic modes of thought, from the attempt to rationally explain processes based on a prior intuition.

The formation and dissemination of such thinking was, to an extent, influenced by the defense and security services community (the Siloviki). Such circles tend to feel that they stand above the society that they protect. At the same time, they exist in a state of constant struggle against threats and opponents, including those hypothetical or imaginary threats that figure in their planning exercises. The most important task of the defense and security community is to foresee threats that the ordinary person misses. This sense of chosenness and work with secret information (secret knowledge) can lead to a conspiratorial style of thinking which, moreover, can leak into the public sphere. This is indirectly confirmed by the fact that in Russia in the early 1990s, people from the military structures created a number of well-known esoteric sects (for example, the KOB, Komitet obshchestvennoi bezopasnosti, or Committee for Societal Safety).

The Church

The restoration of churches and parish life in the new Russia led to the gradual rehabilitation of church language in the public domain. For the first ten years after the fall of the Soviet Union, Russian TV presenters struggled to properly pronounce the names of Orthodox holidays and liturgical terms, usually getting the stress wrong and stammering around. It’s not just that such vocabulary didn’t exist during the Soviet era: It was taboo. It was beyond the bounds of acceptable discourse in the Soviet period. But with time, this situation was overcome. Today the general public has learned to understand church vocabulary, and the Church itself now talks with outside society more and more with an everyday language. In short, it is at this coming together of the specific Church and an everyday, “secular” vocabulary that the modern language of the Church has been formed, and by now it influences all spheres of society—and this influence extends as well to the meaning of the word “Russians.” Today in the Russian Orthodox Church there are two basic perceptions of the Russian theme.

The first, based on the experience of the above-mentioned community of “Russians abroad,” fully reflects the latter’s aesthetic and political stylistics in which “Russianness” refers to the higher, more-educated classes, anti-Bolshevism, and nostalgia for tsarist Russia. It is characteristic of those Orthodox believers and clergy who consider themselves members of the intelligentsia, but it also has a colossal influence on the rest of the Church.

The second approach to “Russianness” is closely connected with folk Orthodoxy, rural life, subsistence farming and ecology. Many parishes perceive Russianness and Orthodoxy through the image of a lost peasant way of life which they are trying to reconstruct. This approach is facilitated by the practices of a large number of modern monasteries that are engaged in agriculture and raising livestock. From this foundation, a whole vector of modern Orthodox folk and environmental stylistics, based on the idea of clean food (monastic bread, herbal collections, honey and other products) has taken off. This neo-village style is popular in modern urbanized society. By linking Russian Orthodox identity with the countryside and nature, the Church has actually created a new ecological subculture.

Both of these Russian identities—both the “diaspora” and the “rural” versions—are developing within the church in parallel and without feuding among themselves. The “diaspora” identity is more influential in matters of philosophy and “ideology” although, in recent years, church-society processes in Russia have become more complex and can no longer be contained by the “diaspora” perspective. Today, the Church is gradually undergoing a transformation, primarily through overcoming the anti-Bolshevik politicization stance characteristic of the Cold War era.

As noted above, the theme of Russian Orthodoxy is actively used by various centers of power (modernists, anti-globalists, neopagans, etc.). However, Orthodox symbolism is for them simply another construction material no different from any other. They are engaged in building their own discourses, which need to be delimited from the language of the Church itself.

Russians

Participants in modern political discussions often draw attention to the fact that in most foreign languages (with the exception of, for example, Belarusian and Ukrainian) there is no concept of “Rossiskii” (Russian national). In German, English, French, Turkish, etc., the same word is used to describe both the nationality and the national home for all our citizens. That single word is: Russians. In Russia, we train our foreign language students and translators to distinguish in which cases it is necessary to render the foreign “Russisch,” “Russian,” “Russe,” “Rus,” etc., as Rossiskii (Russian national), and when as Russkii (Russian).

The foreign holistic perception of our society as a simple unity—as summarized by the single word “Russian”—is experienced as a part of everyday life when you find yourself abroad. There, as a visitor, regardless of what sub-nationality you may belong to in Russia, you are still referred to as a “Russian”. Russian Olympians at competitions in foreign countries, it turns out, are simply Russian atheletes. What is more, this foreign reference to “the Russians” influences our self-perception of our national home after we get back to Russia. In the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Army, one frequently meets with this sort of reference to oneself as Russkii in a sense that is stylistically close to the English “Russian”. That foreign partners and potential adversaries refer to us as Russians and not as Russian nationals has an impact. Additionally, there is the impact of the memory of our past wars, and primarily the Great Patriotic War [WW II), during which the Germans waged war not against Rossiyane, not against the multinational Soviet people, but against Russians. The Great Patriotic War sacralized the concept of Russians, freeing the word from a narrow national connotation by making it something value-laden, something with a historical-cultural significance, coextensive with the entirety of the people.

Russian Literature

Today, Russian classical literature remains almost the only domain where the full complexity and at the same time the integrity of the notion of the Russian people has been retained. In terms of coverage and depth, it is far ahead of all the above-enumerated perspectives, including the memory of the experiences of big wars. Russian literature has described Russians as a people oriented to profound moral and religious searchings, and yet without the urge to dogmatize; as Christian and in possession of a universal, Catholic, consciousness, and yet opposed to globalism; underground (in the Dostoevskian sense), and yet intolerant toward spiritual marginalization or lumpenization; as understanding the universe through the prism of one’s own soul, and yet rejecting as alien nationalistic ethics.

Classical literature cannot independently transform modernity. Despite its sincerity and grandeur, it inevitably serves as an instrument in the hands of the mighty “of this world”. Literature is a most valuable resource, but it is not a political force.

***

We should not let ourselves be lead astray by the tragic fragmentation of the concept “Russian” in the modern Russian language. The multiplicity of connotations to the word Russians is evidence not of the weakness of Russian identity, but of the diversity of forces that are fighting for the right to interpret it.

After the collapse of the USSR and the end of the existence of the Soviet people, the term “Russian nationals” (“Rossiyane”) was introduced. During the 1990s it became clear that this term had failed in its task of defining an all-inclusive national identity. The concept of being a Russian national (“Rossiskost”) born during the crisis of statehood, remained an unformed idea symbolizing the ersatz-nationality of the era of radical liberalism. During this same period, a painful and spontaneous search for a new national idea began, one which was stopped almost administratively under the new leadership in the early 2000s, when the futility of these searches became apparent. With the coming to power of Vladimir Putin, a great era of foreign policy began, during which the logic of political thinking proceeded from the priority of the international over the domestic as far as Russia’s future was concerned. Most of the political victories of this period were connected with foreign policy: the repelling of aggression during the “five-day war,” the foundation of the Eurasian Customs Union, the Olympics in Sochi; Crimea; Syria. Even in domestic politics, the main transformative moments have been associated with attempts to tame the forces of aggressive foreign capital in the information and economic spheres. Over the past seventeen years, Russia’s international identity has become so strong that it has become more prestigious to be associated with the name of the country, than with the name of its people. In modern Russian political language, Russia is more than the name of a state. It is a civilization, a fate, and a responsibility.

This era has fulfilled its task and it is coming to its end. If we are talking in terms of the scale of Russia’s international identity, in today’s conditions, it has already reached its maximum. Today’s political leadership realizes with perfect clarity that the further development of the nation will require special attention to its internal identity.

______________________

Vasiliy Shchipkov, PhD in Philosophy, is a lecturer at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO) and a Director of “Russian Expert School.” This article is based on the author’s chapter in the book Language: A Collection of Essays on Russian Discourse (Moscow, 2017; available in Russian at http://shchipkov.ru/object/000519.pdf). The author expresses his gratitude to Paul Grenier (Simone Weil Center for Political Philosophy) for his help in translating the article.