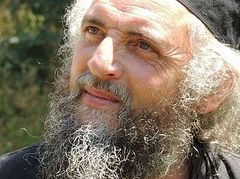

The outstanding spiritual writer, iconographer, opponent of modernism and ecumenism, and cleric of the Georgian Orthodox Church Archimandrite Lazar (Abashidze) reposed on August 17, and his fortieth day was commemorated recently on September 25.

I was a seminarian once and had a lot of dreams—about life, about the future, about the Church, about the fight between good and evil and my part in it. These dreams were different and sometimes very inspired. They had one main, deadly flaw—they were just dreams. How detrimental reverie is for our spiritual lives!

Then one day the book On the Secret Ailments of the Soul by Archimandrite Lazar fell into my hands. Despite its small size, it effected a huge change in me.

I read it, finding instructions for myself on every page—a vibrant and passionate word, which, like a surgeon’s scalpel revealed my spiritual afflictions and removed my sinful tumors. This little booklet of Fr. Lazar turned everything upside down within me and became a kind of revelation that awaked me to authenticity and awakened me spiritually, to not live by dead fantasies and dreams.

Some books are read and forgotten, but this little booklet really worked on my soul and has been preserved in my memory my whole life. Why? Because the true value of a book is not in the number of pages, not in the amount of paper eventually turned into useless waste paper, but in how it works on the soul, in how much the book is able to awaken and transform us.

Archimandrite Lazar (Abashidze) is a spiritual author of our era, a sincere servant of Christ, an heir to the spirit of St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov). In his works he preaches a non-dreamy, sober Christianity, as St. Ignatius used to preach.

Archimandrite Lazar’s books became a great spiritual aid for many. The Torment of Love, Sin and Repentance in the Last Times, To the Soul Burdened With the Spirit of Despondency, and others are a valuable guide for Christians of our times. They are written on various literary levels and can be useful to this or that person in certain life situations, but I would strongly recommend that every modern Christian read Fr. Lazar’s book On the Secret Ailments of the Soul.

Not personal, subjective speculations, but the truths of the ascetic holy fathers, imbibed by the heart of the author, were realized in his personal life and therefore so act upon us—this is what we find in Fr. Lazar’s books. This is the path that leads to salvation.

Archimandrite Lazar’s main merit as a spiritual writer of our times is that his words were sobering, helping you to realize your true situation and, pushing off from there, to move forward. Can there really be any movement in an impenetrable fog? The fog that dims our eyes is our opinion about ourselves, our dreams and fantasies, and our complacency after our first difficulties in the spiritual life. A sober vision of ourselves, of our penchant for every falsity and enticement is important on the spiritual path; it is important to have sight of the approaching temptations and enticements. Fr. Lazar shares this vision and the possibility of attaining it with us.

The spiritual path in life is not easy. Seeing obviously grievous sins within ourselves, we are humbled and we repent fervently and zealously. But when our outwardly obvious falls are cut off, it’s easy to fall into complacency, as our opinion of ourselves arises: “I have overcome so much and born such fruit;” it’s easy to fall into laxity and self-complacence.

Fr. Lazar rightly says, “It has become a common disease in our times: People now—according to the lasciviousness ingrained in them and the propensity to seek comfort and agreeableness always and in all things—understand the spiritual life itself as a means of more quickly receiving this internal ‘bliss,’ this sweet peace, this euphoria.”

And the most terrible thing is lukewarmness, when we begin to say to ourselves inwardly: “Things are not so bad with me: I go to church, I confess, I commune, I help people…” The soul gets stuck in the temporary comfort of rest and ceases to see its own shortcomings, not responding to hidden, secret mistakes and sins with pain—because they are all in the depths, not open to the overt external view. Such a soul ceases to work on itself and gradually retreats from God.

Fr. Lazar ceaselessly testifies: Christianity is not the easy stroll of a curious tourist, enjoying some previously unseen spectacle; Christianity is the arduous work of cultivating yourself, your soul, and all your inner sensibilities and powers. Christianity is very serious and very responsible.

To see yourself as you truly are is the beginning of the spiritual life, although this beginning is very painful. Starting from this sober conception of yourself, it’s possible to begin building a spiritual life and to overcome your specific shortcomings.

One of the temptations of modern Christians that Fr. Lazar warned about is the desire to quickly free ourselves from our passions and be accounted worthy of Divine gifts of grace. It would seem we are pursuing quite a pious goal—to serve God with the help of gifts of grace and to help people. But behind this attitude lies, firstly, ignorance of our fallen nature, and secondly, a mistake in our identification of the very purpose of the spiritual life.

Salvation is not in attaining supernatural gifts but in receiving the Savior. A savior is necessary only to those who are perishing. He who considers himself free from passions neither sees, nor understands, nor feels why he needs a savior. Salvation is possible only through awareness of our fall. We are waiting for speedy redemption, but the healing of the soul occurs very slowly.

Fr. Lazar repeats this ascetic truth. Our passions are healed very slowly. They can lurk, not showing themselves, so it sometimes seems they don’t exist at all, but relaxation brings with it a fall. As the ancient Christian ascetic Abba Isaiah rightly said:

Until a man’s very end, the passions retain the ability to arise in him, and he does not know when and which passion arises: Thus, as long as he is breathing, he must not forsake vigilant observation over his heart; he must ceaselessly cry out to God, entreating His aid and mercy.

In this sense, Christianity is always work, always activity, and never ease or blissful rest. As Fr. Lazar reminded, in Paradise there are none who are not crucified, and if you do not want Golgotha, then you will not be found worthy of the Resurrection (in the spiritual sense, of course).

In confession, we all repent of our infirmities, of our repeated sins, and we sometimes wonder why the Lord does not deliver us from the activity of our passions. After all, we pray, we repent, we entreat—where is our liberation? But it turns out that it’s often not good for us to receive speedy deliverance from our infirmities. This is how Fr. Lazar describes it:

Of course, the Lord can cleanse us of all our infirmities in but a moment, but the Lord is pleased with our humility and our repentant, prayerful state; but a speedy liberation from our ailments would cause in us a proud, self-righteous, inactive spiritual disposition.

We must always remember such spiritual truths.

Archimandrite Lazar’s spiritually sober realism may seem too harsh to some: We’re used to being comforted, reassured, and entertained. In the spirit of his works, and in their same style, Archimandrite Lazar—a successor to St. Ignatius—is an exponent of his ascetical direction, the same kind of uncompromising teacher of repentance and vision of our sin, overthrowing every false idol of false opinions about ourselves.

But especially important: Fr. Lazar did not impose himself, his teachings, his spiritual guidance on anyone, and did not interfere in public life, didn’t organize any kind of movement, but led a meek monastic life, wholly dedicating himself to Christ. Humility and sincerity distinguish all his works.

Fr. Lazar did not claim the role of an elder or a proclaimer of high truths; in his books he humbly shares the pain of his heart, he sympathizes, and he writes as though it were the confession of his soul. And as regards discipleship in our days, he speaks frankly: “It is true that it has become unsafe to trust, that you won’t find truly experienced elders—they’re very hard to find—but many make themselves into ‘elders,’ and you can’t seem to shake them off.” Where there is no overblown “I,” where there is humility, meekness, and quiet service to Christ—only there is genuine guidance possible. Such was Fr. Lazar’s own path.

He was not afraid to defend true spirituality, morality in the education of children, and purity of Orthodoxy in the modern theological environment and in inter-confessional dialogue. However, all the while, the voice of Fr. Lazar remained the voice of a heart that was humble, living, and passionate, and therefore which tried to protect others from any destructive infatuations.

The value of Fr. Lazar’s works is that you can feel genuine life in them—not a languid narrative of abstract morality, not any reading that stirs the passions, but the words of a living, awakened soul, drawing the reader to his own awakening.

Now Fr. Lazar has passed on to Christ, has left this bodily temple and parted with this vale of sorrow and suffering, but, as a spiritual author, Fr. Lazar continues his conversation with us, trying to call us out of our state of complacency and lead us out of the whirlpool of our steady, carefree, and self-deceiving lives. May God grant us to follow him in this!

Fr. Lazar was a sincere servant of Christ; all his life, all his heart, all his talents—as an author and iconographer—were dedicated to the Savior. Grant him eternal salvation, O Lord! Grant rest, O Lord, to the soul of the newly-departed Archimandrite Lazar!