How can we explain the Orthodox faith to outsiders during a friendly ten-minute chat “on equal terms”? Why do we take pride in our faith and strive to preserve its purity? How can we refute the claim that “Christianity is a religion for weak-minded people”? Can we compare Christianity with Judaism and Islam? Answering questions like these, we need to take into account that the language of the Holy Scriptures and the Church Fathers (which is so familiar to us) is often unintelligible to unchurched people. The use of such words as “grace” and “redemption” usually puzzles them. Fortunately, there are a number of ideas that are of paramount importance for all people living in this world and which enable us to carry on a meaningful dialogue. One of these ideas is gratitude, or thankfulness.

According to G K Chesterton, the religious education of a child begins not when his dad speaks with him about God, but when his mom teaches him to be thankful for a tasty cake she has baked. A living sense of gratitude is the driving force of faith, like a clockwork spring.

Any religion offers us its sacred history. Its cosmology, and its drama of the relationship between the heavenly and the earthly realms resemble the winding up of a spring: the story of what God has done for man determines the degree and nature of the latter’s gratitude to his Creator. And a burning question arises: what can I do to show my appreciation of His blessings? Sacred history throws a challenge to humanity: the fact that we cannot ignore this situation makes it (the situation) special. Any action, including an attempt to pretend that nothing special has happened, will answer this challenge.

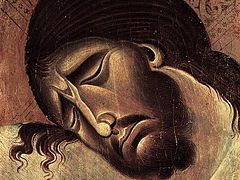

According to Islam, the Almighty created a great, wonderful world and commissioned man to rule it. Judaism gives some more specific information and adds that among all the tribes and nations in the world the Creator appointed the Jews to be His chosen people and promised that they would produce the messiah in due time. And it says that as a holy nation they are called to teach all other tribes and rule over them. Yet Christianity is something greater: It is a glorious and tragic story of the life of God on earth—a God Who “was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered, and was buried. And on the third day He rose again according to the Scriptures.”

The “most ancient evil” that man was ever faced with was death, which would put an end to human life. The only “remedy” for death could be eternity, life everlasting. But only God is eternal, and despite His omnipotence He is unable to create another god co-eternal with Him. Thus, neither a prophet, nor an intercessor, nor an angel can save human nature; only “the grafting” of divinity can do this. This is where the Incarnation of God—the basic teaching of Christianity—stems from.

Let us imagine a plague-stricken city. A young doctor who claims that he has found a remedy for this fatal disease arrives in it. The remedy has not been tested yet, though. However, the medical ethics (one of the principles of which is non-maleficence – “don’t be a cause of harm”) doesn’t allow him to try out the new drug on humans. That is why physicians used to try out new drugs on themselves. But the young doctor is healthy. So he deliberately comes to the city residents to contract the disease from them. Once the infection has reached the stage he needs, the doctor leaves them and takes his drug1.

This is precisely what the Lord did as well. Though He knows no need and no suffering, Christ deliberately “infected Himself”—that is, took on new, mortal human nature. When we teach our children how to swim, we enter the water together with them. If you want people to learn to rise from the dead, you need to die with them. So Jesus, the Son of Mary of Nazareth, was exposed to suffering and death. The Son of God, He is the very God Who created the heavens and the earth.

Absorbing the infected blood, the doctor purifies and heals it with his medicine. Having overcome the malady, he does the blood transfusion to his patients using his purified blood which contains antibodies. Christ said to His disciples during the Last Supper: Drink ye all of it; for this is My Blood of the New Testament, which is shed for many for the remission of sins (Mt. 26:27-28). The priest pronounces the same words during the Divine Liturgy.

“Eucharist” comes from the Greek word meaning “thanksgiving”. An ungrateful person has no right to call himself a worthy man even if his life was wholly devoted to charitable actions. The early Church with its strict discipline would automatically excommunicate those who ignored the Eucharist (the Holy Communion). Let us imagine the following situation: somebody from the bottom of his heart spends his salary on the best gift for his friend that he can afford. But the friend looks at the gift indifferently and throws it in the trash can, saying: “I don’t need this! I expected you to give me something better.” Alas! Many of us do the same so often! Every time we go past the sacrificial cup of the Body and the Blood of Christ we reject God’s helping hand (pierced by the Roman nail) extended to us: “We aware of Thy Passion. We do sympathize with You, but we feel good and don’t need Your sacrifice.” According to a subtle remark of the poet Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941): “To find joy in bread—that is the greatest gratitude.”

Islam doesn’t call on us to be perfect because it tells us the story of an omnipotent god who thinks nothing of bestowing a gift on us. The very word “Islam” means “submission”, “obedience”. For this religion giving thanks to God means using His gifts with solicitude, without rejecting or abusing them. This can be achieved through observance of the religious law with humility—certain “directions for use of this world”. Judaism suggests that the gratitude to the Creator should be expressed by the responsibility of each Jew to God for the whole of the chosen people and his faithfulness to God. But how does a Christian give thanks to his crucified God?

Thanking a god who made no effort (as in Islam) is one thing, but offering a sacrifice of praise to Him Who delivered Himself up to agony and death for us is another thing. A partial sacrifice won’t suffice here. A tithe of one’s labor or crops will also be out of place. It becomes us to offer a full sacrifice to Him Who gave His life for us—this offering should be no less than one’s life, the greatest treasure that a human being can possess.

If there is submission in Christianity, it is an absolute submission which extends to cutting off of one’s own will. If there is faithfulness here, then it is faithfulness “even unto death”. The perfect joy of deliverance from a debtor’s burden is the joy of a martyr who is parting from his body and peering into the heavens which are so dear to his heart, anticipating the promised words: Well done, thou good and faithful servant: …enter thou into the joy of thy lord (Mt. 25:21).

The challenge of divine love measures the whole human being by itself, leaving nothing that’s “human, too human”. Even the weaknesses that emerge in one’s mind and are seemingly socially innocent and not punishable by law are regarded as sins here because striving to be “just a good person” rather than a saint is nothing more than an attempt to pretend that there was neither the Incarnation, nor the Crucifixion, nor the Resurrection. That is why we find the following words in the Gospel: Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect (Mt. 5:48).