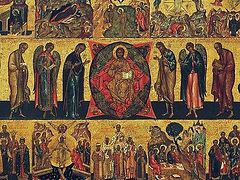

You have probably all seen certain pictures of the saints—usually Western pictures—in which all the saints look more or less the same: the same doe-eyes, the same piously folded hands, the same soft, feminine features found on both women and men. These images offer a particular view of sanctity, proclaiming sanctity as soft, meek, harmless, quiet—and utterly ineffectual. Looking at these pictures you would never guess that those saints were real people, men and women with distinctive—and sometimes sharp—personalities, people capable of wit, anger, regret, and repentant tears. Nope: those feminized saints can’t be real people like us. They are utterly different—and therefore utterly irrelevant.

You have probably also read hagiographical accounts of the saints which function in the same way as those feminized Western pictures. In these accounts, all the saints are more or less the same: they all do amazing miracles, they all exude sanctity and sinless perfection, and they all never, ever do anything wrong. Reading story after story of different saints in these hagiographies, my eyes tend to glaze over as the saints melt into one another and become more or less interchangeable. Their names and dates and locales may be different, but their distinctive struggles, failures, victories—and therefore their personalities—have all been sandpapered away. Doubtless such hagiographies had and have their uses. But if you want to encounter the saints as they really were in these stories, you will be disappointed.

Take for example the exchange in Constantinople between St. John Chrysostom and St. Epiphanius. The latter was a great heresy-hunter, whose prestige and help had been solicited by Theophilus, bishop of Alexandria, who secretly intended to take down his rival Chrysostom. In other words, Epiphanius was used by Theophilus—some might say suckered—and Epiphanius arrived in Constantinople to sniff out and eradicate Origenism from the capital. Theophilus had told Epiphanius that John was an Origenist, and Epiphanius believed him, and so the venerable old fighter came to Constantinople prepared for battle. Epiphanius’ attacks on John’s orthodoxy came to nothing, of course, and in a few days he left the capital, bitter and disillusioned.

According to one church historian (Sozomen) when Epiphanius was met at the quay by a number of bishops who gathered to see him off, he said to them, “I am glad to leave you with the city, the court, the whole wretched show. I am off home as fast as I can”. Another story related by the same historian recounts that before boarding the ship home, Epiphanius sent John a note saying, “I hope you will no longer be a bishop when you die!”, to which John is said to have retorted, “And I hope you will not set foot in your city again!” Ouch. Whatever the actual historical truth of the matter, it is clear that the two men had little love for one another, and each was glad to see the other go. In other words, Epiphanius and John were both real people.

Too real, as it turns out, for the hagiographers. In one sanitized account, their exchange reads as follows. “Chrysostom heard that Epiphanius had agreed with the Emperor against him. Chrysostom therefore wrote him a letter: ‘My brother Epiphanius, I hear that you have advised the Emperor that I should be banished. Know that you will never again see your episcopal throne’. To this, Epiphanius wrote in return: ‘John, my suffering brother, withstand insults, but know that you will not reach the place to which you are exiled’. And these two prophecies of the two saints soon came about. Epiphanius took ship and set off for Cyprus, but died on the voyage. The Emperor sent Chrysostom into exile in Armenia, but the saint died on the road”.

In this version, we see little if any rancour between the two saints: for John, Epiphanius is “my brother Epiphanius”; for Epiphanius, John is “John, my suffering brother”. They don’t exchange bitter or angry barbs, but prophecies. This is not history, of course. It is “spin”. And it has the unintended effect of making both Epiphanius and John rather less like real people, and more like the interchangeable porcelain figures one sees in those feminized Western images.

I suggest that to appreciate the saints fully, we need to see them as real people, men and women who made mistakes, who had bad days and as well as good ones, and who knew how to repent. We can admire the porcelain figures of the Western images and the hagiographies, but not really love them. To love the saints, we first need to see them as they truly were.

It was for this reason that I written a book that attempts to get behind the spin-doctoring and to see the saints as they truly were, trying my best to unite loving piety with historical accuracy. Obviously such a large task is beyond the competence of any single person, including me, but a beginning must somehow be made. Sometimes we know a lot of historical details about the saints; and sometimes we know very little. But ultimately our relationship with the saints depends not upon our knowledge of them, but their knowledge of us. If we get some historical details wrong, no doubt they will be happy to correct us when we meet them in the age to come. Until then we can love them, rely upon them, and ask for their prayers. And enjoy learning as much about them as we can. If you would like to learn more about them, my book A Daily Calendar of Saints, can be ordered here.

I don't think we today are sober enough to dwell on the imperfections of the saints. Look how giddy some become when discussing St. Nicholas punching Arius. Is it really joy for his defense of truth, or is it revelry in the taboo of "Santa" hitting someone? I think the latter.

I wouldn't say sanitizing the truth is good either, but is it best to meditate on the saints' failures or their successes?