Any Christian can tell you about St. Nicholas. Almost everyone knows that he helps travellers, helps poor maidens get married, and brings us Christmas presents under the name of Santa Claus. Many recall how he slapped Arius in the face at the First Ecumenical Council of 325, and there are so many folk legends and fairy tales connected with the name of St. Nicholas that they could fill a heavy volume in various languages.

Meanwhile the Life of St. Nicholas makes us look at this famous Christian saint in a completely new way. The most well known text dedicated to the saint was that of Simeon Metaphrastes. Written in the tenth century, almost 700 years after the saint’s repose, it is a compilation from the Lives of two St. Nicholases. The first lived at the end of the third to the first half of the fourth centuries, and the second, Nicholas of Pinar, lived in the sixth century and died on December 10, 564. The familiar Life of St. Nicholas of Myra in Lycia, which we can find in the compilation by St. Dimitry of Rostov, names his parents as Theophan and Nonna. In fact, those were the names of the parents of St. Nicholas of Pinar, about whom Archimandrite Antonin (Kapustin) wrote back in the nineteenth century. From the Life of the St. Nicholas who lived in the sixth century, the story of how the young priest journeyed to Palestine to venerate the holy places got into the life of the other St. Nicholas. The older St. Nicholas died no later than 337. Already as a bishop he suffered from the persecutions of Diocletian that had begun in 305, while St. Helen, the mother of Constantine the Great, discovered the Honorable and Life-Giving Cross of the Lord no earlier than 326.

The combining of two saints with the same name but living at different times has happened more than once in the history of Christianity. Before the twentieth century, researchers often united the images of two righteous ones into one, and as a result the more famous saint would “swallow up” his lesser-known colleague. That is precisely what happened in St. Nicholas’s case. Only at the beginning of twenty-first century did a group of Russian scholars publish a Life of the Archbishop of Myra in Lycia, corrected according to the ancient manuscripts. As a result, we can learn much that is new about the life of Russia’s most well known and beloved saint. In the twentieth century, research on the saint’s relics was also conducted, which confirmed the authenticity of the Life of St. Nicholas even in those areas that are traditionally considered as hagiographic topoi (texts common to all hagiographical literature).

The ancient story of the saint begins with the traditional Life formula of the “fasting infant”: “From the first days of his life, the infant’s behavior was not ordinary: When nursing Nicholas sucked milk only from his mother’s right breast, and on Wednesdays and Fridays he ate only once a day, and at that in the evening, just before the ninth hour. This sign foreshowed Nicholas’s whole manner of life. Thus, from his very infancy to his very death the saint spent Wednesday and Friday in strict fasting and temperance.” Usually comments on such fragments talk about the tradition of imitating the ancient ascetics, and this explanation is not without some basis in fact. Byzantine and ancient Russian hagiographers oriented themselves when composing the Life on famous stories of righteous ones on a series of rhetorical devices, which all together formed the canon of saints Lives. In Byzantium the canon of the monastic saint’s Life (biosa) came together by the sixth century, and the graduation exam for many rhetors became the description of a large biography of a saint. Despite the fact that St. Nicholas lived in the fourth century, the first hagiographic compositions dedicated to him appeared several centuries later (not earlier than the seventh century), when the genre of saints’ Lives had been finally formed, so that hagiographers could make full use of the saints’ Lives topoi, taken from more ancient texts.

Nevertheless, in the case of St. Nicholas, the anthropological research of his relics conducted at the opening of his tomb in Bari by Professor Luigi Martino in 1953 – 1957 showed that the saint ate only plant foods.

Along with this, in the corrected Life of the saint we can also find true topoi, which describe the ideal behavior of a child in Byzantium: “Never were there noticed in Nicholas any habits customary to youth. The righteous child was like an elder—all respected him and were amazed at him. When an old man displays youthful diversions, he is a laughing stock to all. But if a youth has the moral behavior of an elder, he inspires respect from all. The lightmindness of youth is inappropriate in old age, but the wisdom of an elder is worthy of honor and excellent in a youth.

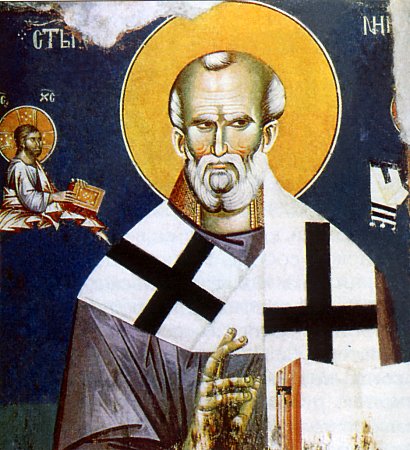

The consecration of St. Nicholas

In one of his articles included in the book, Poetry of Byzantine Literature, Sergei Averintsev accurately discerned that Byzantium saw the ideal child as a “little, prudent old man.” Ancient Russian authors inherited this point of view, and as a result St. Theodosius of the Kiev Caves and many other saints started disdaining childish games and behaving like soft-spoken elders made wise by experience. Naturally it is impossible to prove the historical accuracy of such information. Only in the Lives of two great nineteenth century saints—St. Seraphim of Sarov and Ambrose of Optina—can we find stories of their liveliness and childhood spontaneity; as for the righteous who lived earlier, we can only guess as to the true stories of their childhood.

But let us return to St. Nicholas. The authors of the corrected Life of the saint refute the idea spread during the nineteenth to early twentieth centuries that we can know practically nothing about the saint’s real life. A new hagiographic text on Russia’s favorite saint gives rather a positive answer to the question of whether or not St. Nicholas participated in the First Ecumenical Council that took place in 325 in Nicaea. Already in the middle of the last century, the famous Church historian Anton Kartashev said that it was unlikely that a modest archbishop of Myra in Lycia could have been present at the council, and even more unlikely that he could have dared to slap the Constantinople priest Arius in the face. Studies of ancient manuscripts telling of St. Nicholas now no longer give any basis for such categorical answers. The authors of the text of the Life and commentary to it, A. V. Bugaevsky and Archimandrite Vladimir Zorin, discuss the reason why complete list of participants in the First Ecumenical Council are not extant: “According to Church tradition, 318 hierarchs were present at the First Ecumenical Council. In the various lists of participants in the Council that have come down to us, written in Greek, Coptic, Syrian, Arabic, and other languages, there are 220 names. However according to reliable testimony by participants in the Council, there were in fact significantly more hierarchs present. St. Athanasius the Great, Pope Julius and Lucifer of Cagliari speak of 300 delegates. Emperor Constantine names more than 300. Over the working time of the Council, the composition and number of its participants changed. Some bishops left due to urgent matters in their dioceses while others to the contrary were arriving (A. V. Kartashev, The Ecumenical Councils (Moscow, 1994), 31 – 32). Possibly this is why there isn’t a full list of bishops present at all the meetings. It is not possible to specify the list of Council participants also due to its protocols. The Emperor forbade making them, because he was tired of the endless arguments of the African Donatists over every letter of the record. Constantine proposed that only the exact, formulated, final decisions of the Council be recorded. St. Nicholas’s name is not on the majority of the lists (which, as we can see, can be easily explained by their incompleteness), but it is present in two Greek lists of the participants in the Nicene Council, one of which was compiled in around the year 500 by the Church historian Theodoros the Reader.”

In other words, in no later than the sixth century was the tradition that St. Nicholas was at the Council so widespread that it ended up in several lists of its participants. Of course this does not automatically mean that St. Nicholas was at the First Ecumenical Council, but neither does new testimony allow us to categorically refute his presence. Furthermore, by 325, the name of the archbishop of Myra in Lycia might have been so well known, if only because he was a confessor who suffered during the last cruel persecutions against Christians. The status of a sufferer for the faith at the beginning of the fourth century was so high that according to testimony from the church historian and contemporary of the First Ecumenical Council Eusebius Pamphylos, Constantine the Great personally greeted the confessors at the Council and kissed their mutilated members. Although from the Life of St. Nicholas we know that the saint was never subjected to cruel tortures, the above-mentioned anthropological study of his relics show that imprisonment left its mark on the saint: “Anatomical-anthropological studies of St. Nicholas’s chest bones and spine show that the saint suffered from arthritis of the spine and, possibly, ankylosis (immobility of the joints as a result of fusion of the joint surfaces). Radiological research on the skull showed an inner thickening of the cranium that was very widespread and clearly manifested. Prof. L. Martino supposes that these mutations in the bones can be explained by the influences of prolonged exposure to cold and dampness, to which the saint was subjected during his long years of languishing in prisons, where he was incarcerated at the age of about fifty.” In the Life itself can found direct references to the fact that in his later years, St. Nicholas could not walk quickly.

This is only a small portion of the puzzles, to which we can find answers through attentive reading of the corrected Life of this saint who is so famous in Russia, whose icon can be found in every home and automobile.

However it seems there is a mistake in the first paragraph:

"The first lived at the end of the third to the first half of the fourth centuries, and the second, Nicholas of Pinar, lived in the fourth century and died on December 10, 564."

Did Nicholas of Pinar live in the "fourth century" or the sixth century?