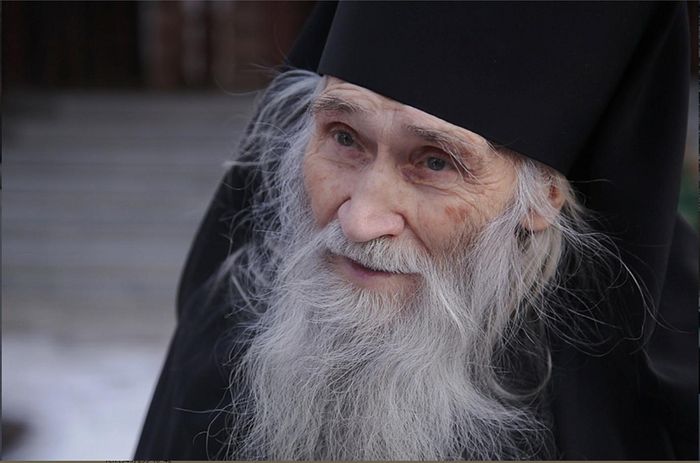

The elder almost never talks about himself. But for the sake of the feast he has made an exception. The following is a story of the Nativity celebrated throughout a difficult, yet joyful life, through which shines the more than two thousand year old history of this event most important for mankind.

—Father Iliy, how did you celebrate the Nativity in the past? Do you remember your first Nativity?

—Oh, I do. That was before the war, and we celebrated together with the whole family. My father was still alive. The churches were already closed back then though. But, nevertheless, on Nativity and Pascha you would always have a sort of special feeling inside and an uplifted mood. It’s a shame that we couldn’t go to church then and give thanks to God. We prayed at home.

Those who were in their adulthood would always try to celebrate the holiday somehow. We as children were always hungry back then, and mother would make us “sitniki” on the holidays, which was just a simple kind of bread baked in the oven. We had our own brick oven then. The smell of an oven heated by firewood and freshly baked bread is incomparable to anything! No kinds of perfumes can compare, no matter how much such fragrances could cost. Nowadays one can’t decide what to choose to spoil himself with. But back then, if you just had bread on the table, then that was already a great joy!

We lived poorly, but there was joy in our hearts. Our house was small, and before the war started we had been thinking of undertaking some construction work. Adults back then were entertaining such thoughts. However, it was impossible! First there was dekulakization,1 then the war started, and then my father was called up to join the army. And that’s where he died in 1942. Our mother then raised the four of us by herself.

From the time before the war I also remember grandfather Ivan Semyonovich—he prayed a lot. He was hot-tempered, but with the help of prayer managed to keep himself together. While the Pokrov Church in the neighboring village was still open, he would help in the altar during services (he was the church warden). And he’d help with just anything in general. He was a jack-of-all-trades. He would make kegs at home and wooden containers of all sorts. He was very careful with measuring, carving and sandpapering everything he worked with. He was skilled at iron work. He’d fix any kind of kitchenware or tools that people would ask him to fix. He did any kind of forging, tin-coating, and soldering himself. He made sleighs. We used one of those sleighs to save ourselves during the war when the Germans forced us to abandon our home.

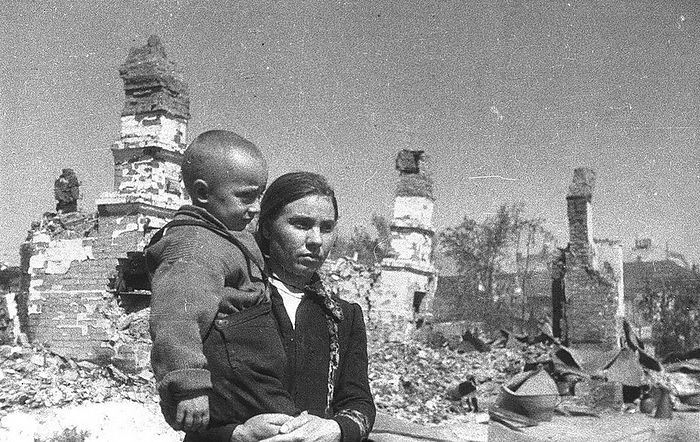

They shook up the entire village in likewise manner. It seems they were looking for partisans who were hiding. Having any ties with partisans would result in you immediately getting shot on the spot. So, our neighbors still had their horse left, and our grandfather had made a sled which we loaded up with some belongings and then aimlessly took off to wherever the road would take us. It was winter and around the time of the Nativity then. So that’s one Nativity that I remember. The cold weather was harsh. But we were happy that we had a horse—although we had no idea where to go or where we could find shelter. But since the Germans were kicking us out, we had to go somewhere…

We rode through our village Red’kino (in 1969 it became a part of the Stanovoy Kolodez’ village of the Oryol district, as a street), and further on was Hotetovo—a large village, about two and a half kilometers long. Riding through it we saw many carts without horses… Their owners had probably already taken shelter in nearby homes. The entire district was stirred up by the Germans. And newcomers were stopped. Whoever had a horse, as it turned out, had it taken away. What to do now?

It was minus 30 degrees Celsius, the lowest was 25. It was evening, and then the night came. We couldn’t find a place for us all to stay. Wherever we’d go, everything was occupied. So, that was it! What could you do? We took a minimum amount of things into our small sled and walked by foot to the next village—Europkino. And there every house was packed, you couldn’t even get in. No-one let us in.

—2018 years ago in the same way no one let the Lord in on the Eve of his Nativity…

—There was one old man that we felt was hesitatingly answering. My mother started crying and begging. He let us in. We slept on the floor I remember. Though I didn’t actually get any sleep. In the morning we ran to Yakovleva village, which was even further away, because we had relatives there—our uncle. We found out that we could go there. We thought we’d go by foot again, but our relatives came to us by horse, without fearing anything they went out to meet us themselves. We lived there for about a month. It was the beginning of 1942 then.

—Were you baptized in Yakovlevo as a child? When you were there again in 1952, was the Kazan church still open?

—No, they had closed it already. But from where we were chased out of, in Red’kino, they’d opened a church by the end of 1941 under German rule. The Germans, of course, weren’t Orthodox. Our people started praying and the Lord helped them.

—Vladyka Iosif (Chernov) once told Fr. Vladimir Divakov about how he returned from exile in 1941, walked into a church in Moscow on the Eve of Nativity, and saw only 10-15 people; and on the next day, on Nativity, there was about the same amount of people at the Elokhov cathedral church.2 It was almost empty. But when the war started—everyone ran for the churches… On Pascha in 1944 in the Resurrection church on Bryusov alley in Moscow there were about 2500 people at the service!

—Yes, the Lord allowed these things to happen. What else could be done, if nothing else would work? And only by the prayers of those who returned to the Church did the Lord save Russia. A godless Russia would have died; but now, on the contrary, it was protected by the Heavenly Powers. The entire territory of our country was actually already divided up by Hitler in his plans.

—How did you survive during the war?

—Well, there were times when we lived in temporary homes. I remember grandfather got lost from us once and we kept moving from place to place again. They didn’t let him come to us then. There were German patrollers everywhere in the area. They stopped everyone: “Stop! Who goes there?” And if you didn’t respond, you’d get shot. It was good if they at least gave a signal first by shooting once in the air. Sometimes they might’ve not felt like sparing an extra bullet for a signal and would just kill you right away. That’s how the people were shot back then.

During the evenings and nights we sat around without any source of light. It was thought that if we had any light on, we might give a signal to the partisans. Of course during our childhood we didn’t have any electricity. What we had was like that oil lamp over there. That was the best we could afford even in times of peace. Glory to God for everything!

There was also hunger during the war. When we returned to where we previously lived, our garden had been confiscated. There was no other way to get food then. And I remember the Germans had such a policy, whereby those who went through dekulakization had everything returned to them. For example, if their homes were preserved, they would get them back. They tried to win the people’s favor this way. Our house at that time was wrecked. Only a small, separately built part of the house remained, and even that was already occupied by some people. Our grandfather asked the new owners to let us live in this little shack, and they let us in and we lived there until spring. ”You can live here for now”, they said. But when spring came, they didn’t let us sow in our garden.

—So how did you survive?

—Little by little. We managed somehow, by the mercy of God. Glory to God! It was difficult, of course. We would sow a little something someplace else. But our potatoes froze up in the ground; and everything else we planted we didn’t get the chance to collect by autumn, because the Germans started chasing us from place to place again. But we survived somehow. (Father Iliy often made long pauses when recalling things, and by his eyes you could tell he still had a clear picture of those times in his mind—O.O.).

There were seven of us in the family then: our grandparents, mother, and the four of us children. Our father was at war. We didn’t find out right away that had already died in 1942. He died at a hospital in Vladikavkaz. I visit there sometimes.

—Did your grandmother believe?

—Yes, grandma Domna—she did, of course. It was hard for her because grandpa was hot-tempered, and she would always try to keep things calm. Grandpa Ivan Semenovich was a bit nearsighted. Maybe that’s why he had such a temper, because he was always kind of inside of himself; he didn’t care what anyone thought and always spoke the truth, which was a bit dangerous back then. He died during the war, just like my father, in 1942. As for grandmother, her aunt took her to Belorussia because of the famine in our parts of the country after the war. And that’s where she died and was buried. She wanted to return home, of course, but wasn’t able to.

It was difficult for everyone back then, not only for us. Even before the war, when everyone was driven into collective farming, everything was taken away from the workmen. Salaries weren’t paid. They’d only draw off checkmarks for the days you worked. Passports were taken away so that you couldn’t move anywhere. Only my aunt, saving herself from the madness, managed to move to Moscow in time. And in the villages even household plots were taxed: From every chicken, if you managed to get any, you’d have to give over a certain amount of eggs. And what if they couldn’t lay any?! And the same for every apple tree. But what if there was crop failure?! And berries from each currant bush, etc. It was simply robbery. Even straw, which was needed in villages to cover the roofs, was gone. You had to give it all up. Can you imagine? Who are those people now that praise the life we had during the Soviet era? Simply no one knows anymore how we really lived back then. The only thing we had was work. There was no time for games or holidays for us children either.

—So, to carol, say, around Nativity time—no-one did that anymore?

—Most of my peers didn’t know anything about that already. But in some families, where the faith was held and where they tried to preserve traditions, even when the churches were being closed, they still had memory of all these things. I don’t know if Varvara Vasilievna is alive or not still—she moved to Livny city. We went to school together; she was from a very religious family. So the kids from that family would go around and praise Christ: “Now Christ is born, therefore glorify Him!” And I hung around with them too and would praise Christ and chant along.

— You had a school right in that very Pokrov church, where your grandfather was a warden before the revolution?

—Yes, we had classes right in the church… And as they destroyed the churches, so they also tried to set up their own kind of order in school. They tried to have their own people there in order to get their ideology through to the students. I only finished seventh grade. That was the kind of education you got back then—seven grades, or ten at best if you were in a city somewhere.

I remember, of course, we had teachers who were Orthodox Christian. Not all of then, but there were some. Geography was taught by a very religious teacher.

When we studied, we had nothing: no textbooks, no notebooks… I remember how we made ink out of beets. The teachers didn’t even have any kind of teaching materials either. They taught us everything from memory. I remember our math teacher Ivan Alekseevich really well. He later helped me with my documents so I could enter technical college.

—Father, when you were at the technical college in Serpuhov, did you go to church there?

—Yes, there was one right next to the college. And in the area there were three more, although there were services only in two of them. The fathers in Serpuhov were gifted preachers.

All of the teachers in our technical college were Orthodox Christians. It’s just that then they couldn’t express their faith in any way. They would hide it in order not to lose their jobs. There was less ideological pressure exerted on teachers in technical colleges than those in schools, as the authorities’ first priority was to corrupt the minds of children.

Though they kept watch over young adults too. I remember being called up once by a KGB agent who said: “I hear that you attend services in church?”

—And what did you say to him?

—“Oh, why should I answer him”, I thought. I mostly attended services in Moscow. My aunt was living here.

—The one that took you to church and taught you to pray when you were little?

—Yes. Her name was Natalya. She was a very pious woman. When they were bombing Moscow, she wasn’t afraid of anything and stayed inside the church praying for everyone.

—And what was the Orthodox side of Moscow like back then?

—I have to say, Moscow was quite different!

I remember one good servant of the Lord, Alexandra, who would just cry over the old Moscow, the solidarity and piety of its people. While another elderly woman, I recall, was always remembering how they bombed the Christ the Savior Cathedral, and would also cry. Such pure and truly pious souls! Knowing how much joy and grace there is in life when you’re with God, they would wish that everyone had such a life and wept seeing how people were destroying for themselves the possibility of a peaceful life here on earth together with the blessed life in eternity with Christ.

—This was before the war?

—Both before and after. And then the repressions lasted regardless of what the people had gone through. Those whom the Soviet regime couldn’t “reeducate”, they exterminated. They either corrupted the people with their godless ideology, or killed them. How many were killed at the Butovo Firing Range, and how many died in Solovki… And I remember that especially before the war there was a lot of obscenity. The youth was being “processed”. Propaganda was working full strength. Although then, of course, there were still many people left from pre-revolutionary times who came from noble families. Moscow was different, and Russia was different!

—And what church did you go to in Moscow?

—The Resurrection Church on the Uspenskaya Vrazhka, on Bryusov Lane. My aunt lived nearby. She was a bit sick then, but she was always very lively, hardworking, and she worked a lot. She helped us live through the worst times of hunger. She lived by herself. Later on she wanted to legally grant me ownership of her living space, but I told her: “What would I need it for?”

—Which church did you attend your first Nativity service in?

—That same one, on Bryusov Lane. Although the most memorable services were the ones we attended in the village in Orlov. But my first service was in the capitol. The church had a very good choir then. There were even some famous singers at the chant stand from the Bolshoi Theatre. And this was actually considered the church of Moscow’s intelligentsia.

—Who served there at the time?

—I remember the rector priest, father Vladimir Elkhovsky. Although there were many other priests there at the time, because most of the churches in Moscow were already either demolished or closed. And then the Kruschev persecutions began…

Kruschev was simply a criminal judging by what he did. How is it possible to let such people to come to power? He initiated a program on the government level by which he promised to show on TV the last priest that would be left alive. He wanted to finish off Orthodoxy in Russia.

But at that time the people had already begun to treasure the church services very much. They had a strong desire to be in church. My aunt went to church very often. She would stand in the St. Nicholas chapel to the left, near the icon of the prophet Elias, one of the oldest icons in the Resurrection Church, and constantly prayed. You could always find her there if she wasn’t at home.

—I know that in those years there really wasn’t much understanding of such a thing as a spiritual father; but was there someone who spiritually guided you when you were young?

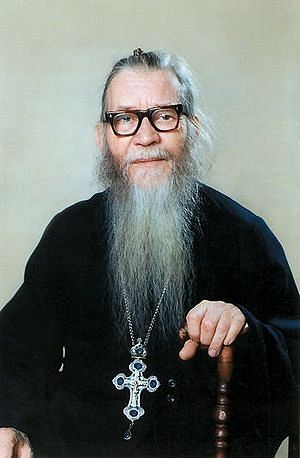

—Father John Bukotkin. But that was in Kamyshin, Vologda. I was sent to work there at a cotton fabric plant after technical college. He blessed me to study at the Saratov seminary and wrote a recommendation letter for enrollment. Then, after all the seminaries around the country were being closed, I was transferred to the seminary in Petrograd (Fr. Iliy intentionally avoids saying the Soviet name of the city [Leningrad]—O.O.). And when I was studying there in Petrograd, Fr. John was already serving in Borovichi near Nizhny Novgorod, which was not so far. And I would visit him there, especially on feast days. Sometimes we’d sit tougher and talk the whole night. And we prayed together.

In 2000, when I was already in Optina Pustyn, Fr. John fell asleep in the Lord in Samara, which is where he had been living for the final years of his life. He was buried there at the Iveron convent.

—What was something you remember about studying at seminary and later on at the academy?

—It was, of course, difficult back then. We began studying in one seminary, and then in 1961 were transferred from Saratov to Petrograd. All the seminaries around the country began being closed after Khrushev came to power. At first there were a lot of us seminary students in Saratov. But right at the time when we were studying there began a harsh anti-church campaign, and they started vigorously preventing young people from studying to become priests. They understood that we were being taught by pre-revolutionary standards. In Saratov and Petrograd we had teachers that were born before the revolution.

The dean of the seminary in Petrograd, I recall, was Fr. Michael Kronidovich Speransky. He didn’t treat us just as a friend would treat his friends, which was something that was becoming more and more common, but treated us with fatherly care. The seminary inspector was Lev Nikolaevich Pariysky. He, by the way, right after the revolution was condemned together with metropolitan Benjamin of Petrograd and Gdovsk. Vladyka together with archimandrite Sergiy (Shein) and two other laypeople, Yury and Ivan, were executed by shooting, and are now New Martyrs; while Lev Nikolaevich along with many others (in just this one case they slandered and arrested 86 people!) was convicted to five years of prison. Our teachers were Confessors of the faith.

When we were studying in Petrograd, the authorities kept threatening to shut down our seminary. Metropolitan Nicodemus (Rotov), who was appointed just then, tried in every way to impede the closure of the seminary. He even opened a “faculty for African Christian youth”, as it was called back then, and invited African people to study there. Kruschev, they say, loved African Americans. For some reason he loved them, but hated his own people… The past century was a time of misery for Russia.

—How did the Lord manifest Himself in those difficult times?

—He allowed those hardships, of course, to happen. Since the communists came to power, it was something the Lord allowed to happen. The people were forgetting God, so He stood aside. He made Himself manifest in the lives of the faithful. The Bolsheviks and communists wanted to completely destroy the Church. What darkness surrounded us from every side then. It was scary, I remember. But we were taught to pray. I knew the Lord’s Prayer from my childhood. I prayed. I could see how the Lord was helping. “The Lord liveth” (Ps. 17:47); He did not allow His Church to be destroyed. It is said: and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it (Mt. 16:18).

—St. Porphirios Kavsokalivit would say that one must turn to God, and He will resolve the problems of his true followers Himself. He makes the following analogy: when a small child sees a wild beast, he doesn’t rush into battle with it, but instantly stretches out his hands to his father and says, “Pa-pa!”

—Yes, one must pray! Fr. John (Krestiankin) also said: “Apostasy is spreading throughout the Earth, but do not try to stop it with your own feeble hand. Be wary of it yourself, and the Lord will give you the energy and strength and wisdom to live with God by His will. This is the way to salvation.” What’s required of us is to pray to God, for He is powerful enough to give us what we need.

—How are we to experience the Nativity of Christ in our souls?

—We must pray. Attend the church services. Receive Communion. The Lord gives us Himself in the Sacrament of Holy Communion. He is our Nativity, He is our Pascha (1 Cor. 5:7). The most important thing is towards what one directs their will. What is it that you want yourself? Are you seeking to be reborn for the spiritual life? The Lord knocks at the door of every soul. He calls us to church, He wants to save us. He gives us everything in life; and not only in this life, but, most importantly, in eternal life. He even sends us infirmities, so that we might ponder on what awaits us in the age to come. If you become sick, then that’s a reminder for you: Pray, prepare for Communion. Sometimes we’re so busy that it’s as if we have no time for God. But when we get sick, we remember Him right away! It’s always like that, whenever we have some kind of problems. Or when a war suddenly starts, everyone runs for the churches.

There is no fear when you’re together with God. He helps.

—What are some of your brightest memories about the Feast of the Nativity of Christ?

—The very atmosphere of the holiday always brings spiritual joy. When a person is with the Lord, then he is thankful to God for everything. “All the glory of the daughter of the King is within” (Ps. 44:14). St. Athanasios the Great explains that this psalm verse is talking about virtuousness, the inner, spiritual beauty of the Church. The very service, by the way, is experienced differently in childhood and adulthood. Even the words of the troparion you experience quite differently as a child. It’s different now as an adult.

—How do you explain the meaning of the Nativity of Christ to children?

—For them, of course, the external aspects are important. It’s good if the service is festive. It’s important that the sermon explains the history of the feast day in a simple way. How they empathize with the Mother of God in the fact that there was no place for her and her Son to stay. The whole story itself is very touching for them, if you create and decorate the Nativity scene for them with much love and care. With a manger, lambs, cows. It’s a great joy for the children. They very vividly imagine the appearance of the angels, the long journey of the Magi, the joy of the shepherds who came to worship the Infant Christ. Of course, gifts should also be given to the little ones, and then they’ll bring their own gifts and promises to the Lord. And so they’ll begin to live with God from a young age.

Our generation had all of these things taken away from us. When I had already entered the Pskov-Caves monastery, one of my obediences was to give tours. I would show the monastery caves. Often around Nativity time, when school students were on vacation, teachers would come to the monastery with the children. Some would attack me saying, “Just don’t tell them anything about the faith!” While others, on the contrary said: “Please tell them more about God, about the Church”. And you’d notice by the kids, that they’re all different! You could tell right away if their teachers were believers or not. The situation in general in schools at the time was as such: The children were not to know anything about the Church. They were trying to completely turn their souls away from God!

At that time I was serving in Pskov and at different parishes. It’s worth mentioning that the Pskov Caves Monastery was the only one in all of Russia that remained opened, and not to mention the fact that over eighty parishes also remained open in Pskov. We monks were often sent to serve there. Back when I was in the Petrograd seminary and was visiting Fr. John Bukotkin, I thought that Nizhny Novgorod would have a lot of parishes. The land was blessed by the ascetic labors of saints such as St. Seraphim of Sarov, and Diveevo after all is called the fourth portion of the Mother of God. But instead I found out that there were only about a dozen churches left that were not closed! There was a very fierce commissioner there who closed down every church he could. But in Pskov the commissioner loved everything that had to do with antiquity, so the churches remained opened there. And Vladyka John (Razumov) knew how to get along with him. So in Pskov there were a lot of parishes that remained open.

—What was celebrating the Nativity in the Pskov-Caves monastery like?

—Glory to God. Metropolitan Nikodim (Rotov) had ordained me a priest by then, so I came to Pskov already as a hieromonk. So on Nativity I would often be sent to serve somewhere in the villages, the parishes, so that the people there could also celebrate. It was good there. Oh, and what churches we had in the monastery! The church of the Dormition, the Archangel Michael, the Meeting of the Lord… (Father Iliy was again returning to the past in his mind, to these dearly beloved places, and was now facially expressing a great sense of joy and gladness—O.O.)

—And what was it like to celebrate the Nativity on Mt. Athos?

—It was different in each monastery. There was always a very festive Vigil followed by Divine Liturgy. The services we had at the St. Panteleimon Monastery were not very long, even for the greater feast days. But at the Lavra services could sometimes last for ten hours.

—How do you, as monks, greet each other on Nativity?

—Each shares his joyful mood with others, and it multiplies and increases. The Lord gives His grace to all of us, to both laypeople and monks. So, share the joy.