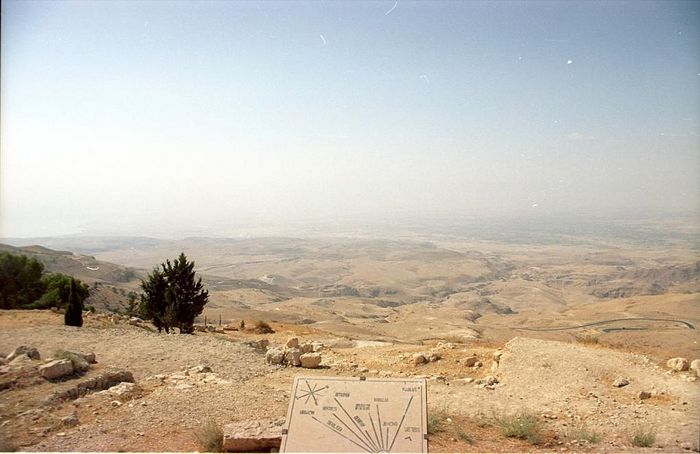

This is the second and concluding post based upon my reading of John McGuckin’s “The Christian Sense of the Desert” in his book Illumined by the Spirit, The first post is Great Lent: Journeying into the Heart of the Desert. The Egyptians understood the desert to be the haunt of demons, especially the evil god Set who brought chaos and destruction to all. They had a great civilization built right up to the border of the desert, but they needed to keep the desert at bey for when the desert moves into the farms and settlements, destruction follows – famine and the towns and farms succumb and become wastelands.

And yet, God called Israel into the desert so that they might see His glory and His face. Christians in turn have seen the desert as “the zone of pilgrimage to the promised land” in McGuckin’s words. We have treated Great lent as that desert zone of pilgrimage which we all can enter so that we can move toward the Kingdom of God. As the Prophet Hosea (2:14) said God allures Israel and us into the desert, not out of it. The desert is a temporary place for us, but an essential part of the sojourn. It is like a bridge we need to get from one place to another. Nobody lives on the bridge but the bridge is essential to all of our lives.

Great Lent as the desert brings us face to face with our own demons. We fast a little and become irritable. Our desires increase, we dismiss self-denial as legalistic. We crave what we want and can see no connection between our lives, our desires, what we indulgence and the Lord God. We come to act as if God was not Lord of the desert – of Great Lent and of my hungering heart – that God is only Lord of my prosperity, of my self-indulgence, of my abundance, of my over consumption. We imagine if we are experiencing the slightest need, then God isn’t there. We act as if God isn’t Lord over everything when we imagine God is only present in times of abundance but not in times of abstinence, self-denial and endurance. And yet the Church’s history and experience is that fasting and self-denial bring us closer to God. The full belly doesn’t cause us to thank God, but to forget God and be contented with the world.

Israel in the Old Testament is not leaving slavery in Egypt for a vacation in a warm climate. They are not even guaranteed a better life by leaving the grand civilization of Egypt for desert wasteland – there isn’t even water in the desert, let alone farms and orchards. They may be slaves in Egypt but they are alive, while the desert means death. They know they are heading into hostile territory, into Set’s domain. Though they have witnessed the destruction of Egypt, they understand they are walking into certain death in the desert. It was there they also would see the glory of the Lord (Exodus 16:7, 10) – strangely, the two go together – facing death and seeing God. In the desert they were totally dependent on the Lord, for the wilderness has little or nothing to give them.

Israel in the Old Testament is not leaving slavery in Egypt for a vacation in a warm climate. They are not even guaranteed a better life by leaving the grand civilization of Egypt for desert wasteland – there isn’t even water in the desert, let alone farms and orchards. They may be slaves in Egypt but they are alive, while the desert means death. They know they are heading into hostile territory, into Set’s domain. Though they have witnessed the destruction of Egypt, they understand they are walking into certain death in the desert. It was there they also would see the glory of the Lord (Exodus 16:7, 10) – strangely, the two go together – facing death and seeing God. In the desert they were totally dependent on the Lord, for the wilderness has little or nothing to give them.

The mystery and the miracle of the desert is that it reveals both the glory of the Lord and also Israel’s own heart. It reveals God’s heart for Israel and where Israel’s heart is. Where your treasure is there will your heart be also (Luke 12:34). As McGuckin writes:

“The desert’s evil, nevertheless, comes out in the manner in which the account of Israel’s wandering stresses the regular failures of the people of Israel to live up to the covenant demands.

The divine call to the desert first comes from God to Israel. They are to withdraw from the fleshpots of Egypt and find themselves once more as the covenant people by sacrificing to their God in the wilderness:

You and the elders of Israel shall go to the king of Egypt and say to him, ‘The LORD, the God of the Hebrews, has met with us; and now, we pray you, let us go a three days’ journey into the wilderness, that we may sacrifice to the LORD our God.’ (Exodus 3:18)

The desert is the place where the glory of the Lord, the Shekinah, appears to his chosen people:

And as Aaron spoke to the whole congregation of the people of Israel, they looked toward the wilderness, and behold, the glory of the LORD appeared in the cloud. (Exodus 16:10)

The wilderness is the place where God himself cares for his needy people:

I have led you forty years in the wilderness; yet your clothes have not worn out upon you, and your sandals have not worn off your feet; you have not eaten bread, and you have not drunk wine or strong drink; that you may know that I am the LORD your God. (Deuteronomy 29:5-6)

And he provides them with manna from heaven: a symbol of provident care that comes once again to the fore in the Christian narratives of eucharistic spirituality (John 6:30-35). …

In the Deuteronomic re-expression of the covenant theology, the wilderness is thus abstracted as God’s time of watching for the veracity of Israel’s faithfulness:

And you shall remember all the way which the LORD your God has led you these forty years in the wilderness, that he might humble you, testing you to know what was in your heart, whether you would keep his commandments, or not. (Deuteronomy 8:2)

Isaiah elevates the desert symbol as a sign of covenant renewal – when the wilderness shall flow with water again (as once it did from the rock); and this became a sign of hope that was specifically used by Jesus himself to describe the days of divine visitation as refreshment and new life:

Be strong, fear not! Behold, your God will come with vengeance, with the recompense of God. He will come and save you. Then the eyes of the blind shall be opened, and the ears of the deaf unstopped; then shall the lame man leap like a hart, and the tongue of the dumb sing for joy. For waters shall break forth in the wilderness, and streams in the desert; the burning sand shall become a pool, and the thirsty ground springs of water; the haunt of jackals shall become a swamp, the grass shall become reeds and rushes. And a highway shall be there, and it shall be called the Holy Way; the unclean shall not pass over it, and fools shall not err therein. (Isaiah 35:4-8)” (pp 126-128)

Great Lent can be the time and place where we learn to live by the Word of God. We learn that we do experience hunger and want and need and yet God is the Lord even in these times. We depend on God and God gets us through the desert by being with us. The small inconveniences we experience as Lent, the hunger, the want, the need, all become transformed into our experience of God. We learn to hunger and thirst for God, we learn how to say no to sin and sinful desire.

Great Lent as desert is also when and where we are enabled to see God’s glory and to enter into it. For in the “desert” we are not distracted by the things of this world – the gadgets, the gourmet, the grand, the gawdy – and so we can see the glory of God.

“…the desert remains in Israelite thought and experience a place where sin and evil are strong.” (p 128)

The desert it turns out to be the gateway to Paradise and the desert and the door to Paradise are both found in our hearts, which is why Great Lent is a sojourn through the heart of the desert and the desert of the heart.

Jesus says: “In the world you have tribulation; but be of good cheer, I have overcome the world.” (John 16:33)

For it is the God who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ. (2 Corinthians 4:6)