Georgian church clergymen and activists unite to protest against a gay pride rally in Tbilisi, Georgia, Friday, May 17, 2013. Photo: news.yahoo.com

Georgian church clergymen and activists unite to protest against a gay pride rally in Tbilisi, Georgia, Friday, May 17, 2013. Photo: news.yahoo.com

Although the Internet is in many ways a blessing, it has also facilitated the hijacking of belief systems. Anyone working—deliberately or otherwise—to corrupt a tradition can spread, and create the illusion of popular respectability to, his false ideas quickly and inexpensively. Whereas previously the Church could maintain a certain level of teaching consistency (e.g., by simply refusing to sell questionable works through parish book stores), she has lost control over the flow of ideas purported to be Orthodox.

Today, the Church is forced to confront ideas—which I would characterize as ultra-liberal ideas cloaked in Orthodox garb—that have proliferated online through various discussion groups and venues like Public Orthodoxy, Orthodoxy in Dialogue, and The Wheel. It is partly on account of this phenomenon, perhaps, that a certain number of Orthodox Christians have adopted the now popular belief that traditional attitudes on sex and marriage necessarily evince hatred towards people living with same-sex attraction. Although there are, to be sure, self-professing Christians whom we may justly call “anti-gay”, in that they go well beyond upholding the Church’s teachings on sexuality, and openly express contempt towards those who do not live in accordance with these teachings, there are many faithful and indiscriminately-loving Orthodox Christians who, on account of the attempt to conflate the two, are being unfairly vilified.

There are, of course, many other argumentative tactics employed against Orthodox social conservatives. Some, like Katherine Kelaidis, have grouped them along with white supremacists, exploiting—it appears to me—our aversion to racism in order to advance a much larger, socially-liberal agenda. (This moral equivalence may help to explain the apparent contempt with which some social liberals view their opponents. I recall one particular exchange on Facebook in which one of the more abrasive members of this movement hurled a vulgar, sexually-explicit insult at a priest. To the person’s credit, the comment was eventually deleted, though not before a screenshot of it had been taken.) Others, while tirelessly working to subvert the Church’s moral teachings, ironically ascribe to their critics—who, as such, would not even exist were it not for these challenges—an obsession with sex.

One of the more common tactics (one with which the remainder of this essay is concerned) is to blame converts for the Church’s conservative stance on sexuality. Indeed, there seems to be a sort of “cradle chauvinism” among some ultra-liberal Orthodox Christians against those who have not yet managed to let go of their “Evangelical moral baggage” (Their attitude towards the “konvertsky” strikes me as somewhat ironic given their otherwise righteous condemnation of bigotry of the racial kind.).

But is it really the case that, were it not for those pesky converts, the Church would effectively become the Eastern counterpart to liberal Protestantism? “Of course not,” many readers will understandably reply. Just strike up a conversation with your average foreign-born Orthodox priest on sexuality, and you will quickly discover the truth of the matter. Be that as it may, it is harder to miss or deny the truth when it is made manifest in a particularly visible way.

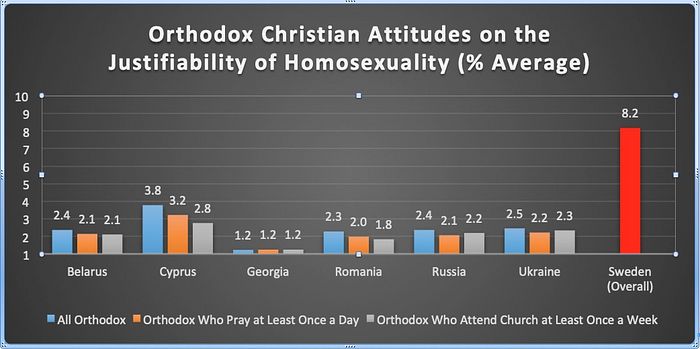

Georgian church clergymen and activists unite to protest against a gay pride rally in Tbilisi, Georgia, Friday, May 17, 2013. Photo: news.yahoo.com Hence I thought it worthwhile to analyze World Values Survey data on each of the six Orthodox countries surveyed from 2010-2014. I was particularly interested in how Orthodox respondents answered what, admittedly, was an awkwardly-phrased survey item, which read, “Please tell me…whether you think [homosexuality] can always be justified, never be justified, or something in between.” Answers were scaled from 1-10, where 1 meant that homosexuality is never justifiable, and 10 meant that it is always justifiable.

Georgian church clergymen and activists unite to protest against a gay pride rally in Tbilisi, Georgia, Friday, May 17, 2013. Photo: news.yahoo.com Hence I thought it worthwhile to analyze World Values Survey data on each of the six Orthodox countries surveyed from 2010-2014. I was particularly interested in how Orthodox respondents answered what, admittedly, was an awkwardly-phrased survey item, which read, “Please tell me…whether you think [homosexuality] can always be justified, never be justified, or something in between.” Answers were scaled from 1-10, where 1 meant that homosexuality is never justifiable, and 10 meant that it is always justifiable.

I was hardly surprised to discover that Orthodox Christians in all six countries expressed conservative views on sexuality. As shown in the chart below, average scores ranged from 1.2 in Georgia to 3.8 in Cyprus (to put these figures in comparative perspective, I also included data on the far more socially-liberal Sweden). Furthermore, those who prayed at least once a day, as well as those who attended church at least once a week were somewhat more conservative than the overall Orthodox populations of most of these countries. This suggests that, on the issue of sexuality, people in Orthodox countries who practice the faith may have more in common with converts here at home than we’ve been led to believe.

It seems, therefore, that it would be wrongheaded to reduce social-conservativism in the Church to the influence of supposedly insufficiently-converted converts. On the contrary, this feature appears to be characteristic of believers in the Orthodox heartlands. Perhaps the dividing line—forgive us, Lord, that there is one—should not be drawn between converted and cradle Orthodox Christians, but rather between those who look to the Church as their ultimate moral authority and those who seek to conform to this world.

Many thanks to Fr. John Joseph Kotalik Lucas (Deacon at St. Seraphim of Sarov Orthodox Cathedral, in Santa Rosa, Caifornia) for reviewing this essay.

Any questions? No, I thought not.

Martyrdom has more aspects than suffering and death brought about by persecution. The Holy Fathers tell us that in times when there is no such persecution, if we endure afflictions such as illnesses to the end, we will gain the same crowns as the martyrs and will enjoy the same intimacy with God.

Sometimes, we see this among Orthodox immigrants, even those of the second and third generation (such as academic Katherine Kelaidis), who always have to be on the "cutting edge" in order to get the kudos of the academy.

Other times, North American-born converts can be tempted by this "keeping up with the Joneses", wanting Orthodox Christianity for its beautiful icons and timeless "spiritual" qualities, but not for the things that produced its martyrs who were willing to give their blood for love of Christ.