Dear friends, we greet you on the approaching Radiant Resurrection of Christ. While looking forward to the feast, we always try to prepare for it properly. There are some peculiarities in the Christian tradition concerning the preparation for and celebration of Pascha. We prepare for Pascha through Great Lent, welcome the Risen Christ at the Divine Liturgy in church (which is the culmination of the feast), and then the joy of our meeting with the Lord proceeds to the festal table and the “tastiest” moment of the celebration comes, namely enjoying Paschal dishes at the first meal after fasting. Today we would like to talk about Paschal dishes—not in the context of cookery but in order to reveal the symbolism behind them.

We have chosen this subject because nowadays every Tom, Dick and Harry dares to speak on Orthodox traditions in the media, though they don’t adhere to this religion and don’t belong to this culture! There are quite a few pseudo-scientific and even anti-scientific articles in which the authors attempt to explain the symbolism of Paschal dishes by pagan traditions, occult meanings and so on, placing emphasis on the forms of the rites rather than the content. I would like to point out that such articles have neither theological, nor historical, nor cultural basis, and that is why we will not make any comments on the opinions expressed in them. So we suggest examining the Christian symbolism of Orthodox dishes.

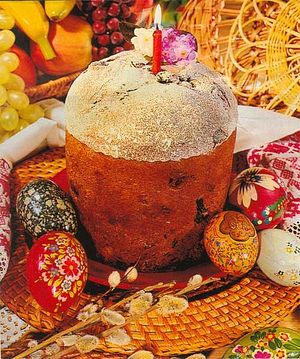

The traditional Pascha dishes include kulichi, pascha cheese, and colored eggs.

1. Kulich.

Among the dishes that are always present on the Paschal table of all Christian peoples is Easter bread, or kulich. Kulich (Greek: “κόλλιξ”, meaning “round” or “oval bread”) is a tall, cylindrical bread of yeast dough which is a domestic equivalent of artos. Artos (Greek: “άρτος”, meaning “bread”) is a special kind of bread in the Byzantine rite which is used in the services of Bright Week.

Among the dishes that are always present on the Paschal table of all Christian peoples is Easter bread, or kulich. Kulich (Greek: “κόλλιξ”, meaning “round” or “oval bread”) is a tall, cylindrical bread of yeast dough which is a domestic equivalent of artos. Artos (Greek: “άρτος”, meaning “bread”) is a special kind of bread in the Byzantine rite which is used in the services of Bright Week.

In order to understand the tradition of the presence of kulichi on Paschal festal tables let us first take a look at the symbolism of the rite associated with artos. First and foremost, it takes its source from the symbolism of the rite of panagia—the prosphora blessed during the Divine Liturgy in honor of the Mother of God as a symbol of Her presence during the meal.

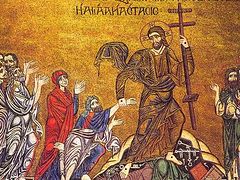

Besides, liturgical commentaries often connect the origins of artos with the apostolic practice: disciples of Jesus Christ found consolation in prayerful commemoration of the Lord. While cooking ordinary food, they would always leave a place at the head of the table for the invisibly present Christ, and place a loaf of bread there. After meal the apostles would share this bread with each other.

Little by little the tradition of leaving a loaf of special bread—artos—in church on the feast of the Resurrection of Christ appeared. It was placed on a special table, following the example of the apostles.

Artos is blessed in all churches after the end of the midnight Paschal Liturgy. After its blessing artos is placed on the analogian, which during services stands by the iconostasis next to the icon of our Lord Jesus Christ; between services the analogian with artos on it is placed near the Royal Doors. Throughout Holy Week, artos is daily carried around the church in cross processions, and after the blessing on Bright Saturday it is distributed among the faithful. According to the Russian custom, the faithful don’t eat the whole artos on that day but reserve it at home, cut it into small pieces and eat it on an empty stomach throughout the year.

Since the family is considered “a little church”, the custom of having a “family artos”—that is, our kulich, was formed. Thus, artos symbolizes the presence of our Risen Lord Jesus Christ at the meal of the most radiant days of the year—Bright Week. And since kulich is a kind of artos by its origin and purpose, it is:

1. A visible expression of the fact that the Savior Who suffered for us became our true Bread of life. That is, kulich is a symbol of Jesus Christ Himself, Who said to His disciples: I am that bread of life… This is the bread which cometh down from heaven, that a man may eat thereof, and not die. I am the living bread which came down from heaven: if any man eat of this bread, he shall live for ever: and the bread that I will give is My Flesh, which I will give for the life of the world (Jn. 6:48, 50,51).

2. Kulich also symbolizes God‘s presence in the world and human life—during our meal we remember the Lord Who is invisibly present among, us just as the apostles while gathering for the meal would leave one place at the table vacant for their Teacher and place an extra loaf of bread for Him. Thus by having kulichi on our tables during the Paschal meal we hope that the Risen Lord is present in our homes as well.

3. A symbol of the replacement of the Old Covenant by the New Covenant, kulich also replaces unleavened bread with itself (Jews would eat matzo—crisps of biscuit of unleavened bread, with bitter herbs and lamb for Passover in the Old Testament). In Christianity leaven symbolizes the vivifying power of the Holy Spirit which gives life to every creature; that is why both kulichi and prosphora are baked using yeast dough—that is, with a leavening agent. This agrees with the words of the Savior about spiritual life and the aspiration for life eternal, which He compares with leaven that is hidden in three measures of flour and causes the dough to rise (see the parable of the leaven: Mt. 13:33; Lk. 13:21). According to St. John Chrysostom: “For as leaven converts the large quantity of meal into its own quality, so you will transform the whole world.” Likewise, through the Baptism in the Name of the Most Holy Trinity the Savior gives the “heavenly leaven”—the gifts of the Holy Spirit and the power of grace—to the soul of every individual person. All three powers (“three measures’) of the human soul (the reason, the emotion [the heart] and the will) grow and rise up to heaven harmoniously, and become filled with the light of mind, the warmth of love, and the glory of good works.

4. There are two opinions regarding the cylindrical form of kulich. According to the first version, this geometrical shape symbolizes the Shroud of Jesus Christ into which St. Joseph of Arimathea together with other disciples and the Myrrh-Bearing Women wrapped the Lord’s Body after it had been taken down from the Cross. According to the second version, the traditional Paschal kulich’s shape resembles a church with its dome. It is no coincidence that kulich is usually marked with a cross on its top.

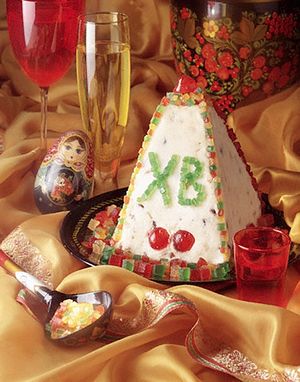

2. Pascha cheese.

Apart from kulichi, it is also a custom among the Orthodox to bless and eat pascha cheese on Easter. In Church liturgical books (the Typicon, the Book of Needs/Euchologion) it is called “thickened milk”—that is, curds or cheese. Interestingly, kulich is called “paska” in the south of Russia and in Ukraine.

Apart from kulichi, it is also a custom among the Orthodox to bless and eat pascha cheese on Easter. In Church liturgical books (the Typicon, the Book of Needs/Euchologion) it is called “thickened milk”—that is, curds or cheese. Interestingly, kulich is called “paska” in the south of Russia and in Ukraine.

To give pascha cheese its proper form it is put into the pascha cheese mold—a small wooden dismountable box in the shape of a pyramid, with the letters “ХВ» [the abbreviation for “Христос Воскресе”—“Christ Is Risen” in Russian.—Trans.]; the symbols of the Passion of Christ—the cross, the spear, and the sponge on the staff; along with a palm branch and a dove—a symbol of the Holy Spirit—are cut into its internal walls.

What is the symbolism of pascha cheese?

1. The shape of pascha cheese symbolizes Golgotha and the Holy Sepulcher, in which the greatest miracle of the Resurrection of Christ occurred.

2. A symbol of the sacrifice of Christ, it reminds us that now the time of blood sacrifices of the Old Testament is in the past. In the Old Testament Passover there was the lamb, which was slaughtered for the Hebrew holiday and prefigured the sacrifice of the Savior on the Cross. The Passover lamb of the Old Testament was replaced with the True Lamb—Jesus Christ. St. John the Baptist uses the image of this lamb when he bears witness to Christ: Behold the Lamb of God, Which taketh away the sin of the world (Jn. 1:29). Sin distorted human nature, and Jesus Christ through the labors of His life and complete obedience to God the Father unto death, even the death of the cross (Philippians 2:8) “straightened” the “crookedness” of our nature. God’s love for mankind is fully demonstrated on the Cross. God commendeth His love towards us, in that… Christ died for us (Rom. 5:8). The entire life of Christ on earth had an expiatory meaning and aimed to reconcile God and humanity. The fruit of the sacrifice of Christ is revealed through the Resurrection of Christ. The Resurrection demonstrates that the Passion of Christ was saving and that our nature was healed from vice, which had been introduced by sin. The Resurrection of Christ marked the beginning of the universal resurrection. The Church experiences the Resurrection of Christ as the mystery of our participation in Divine life, immortality and incorruption.

3. Pascha cheese has one more symbol. Addressing Moses, God promises to give the chosen people a good land and a large…, a land flowing with milk and honey (Exod. 3:8). This description of the Promised Land persists throughout the Passover narration—the exodus of the Jews from Egypt to Palestine. It is a prefiguration of the Heavenly Kingdom, a journey which for a believer is even more difficult than the forty years of the Israelites’ wandering in the desert. Its “milk and honey” is a symbol of everlasting joy, the bliss of saints who were found worthy of salvation and eternal sojourn before the Throne of the Almighty. Therefore, pascha cheese is also a symbol of the Paschal joy and the sweetness of life in Paradise. Pascha cheese is often made into the form of a mound, a hill, which, in its turn, symbolizes the Celestial Zion—the permanent foundations of “New Jerusalem”—the city that has no temple, for the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are the temple of it (Rev. 21:22).

3. Colored eggs.

Since olden times Orthodox Christians have observed the pious tradition of giving eggs to each other on Pascha. A distinctive universal Christian tradition which goes back to the first century A.D. is to dye Paschal eggs.

Since olden times Orthodox Christians have observed the pious tradition of giving eggs to each other on Pascha. A distinctive universal Christian tradition which goes back to the first century A.D. is to dye Paschal eggs.

According to tradition, when after the Ascension of Christ St. Mary Magdalene came to Rome to preach the Gospel, she came to the palace of Emperor Tiberius and proclaimed the good news of Christ’s Resurrection to him. In that era anyone who appeared before the Emperor was supposed to bring him a gift. But Mary Magdalene was very poor, so she presented Emperor Tiberius with an ordinary hen’s egg. The custom of giving eggs can be traced to pre-Christian times. Asian peoples presented them to one another as a mark of respect on New Year’s Day, for birthdays and other special occasions.

Tiberius didn’t believe the myrrh-bearing woman and replied: “How could anyone rise from the dead?! It is as impossible as it would be for that egg to change from white to red.” Immediately the egg turned red under his very eyes as a sign from God to illustrate the truth of the Resurrection of Christ. Thenceforth Christians began coloring eggs on Pascha and giving them to one another with the words of the Paschal greeting.

Following the example of St. Mary Magdalene, we give each other red eggs on Pascha, proclaiming the Lord’s life-giving death and professing His Resurrection—the two events united by Pascha.

Thus, the Paschal egg reminds us:

1. Of one of the main dogmas of our faith and is a meaningful sign of the blessed resurrection of the dead, the guarantee of which is the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, Victor over death and hell. The Life-Giver rose from the tomb, the place of death and decay, and one day the departed will rise again to eternal life just as the new life is born from the egg, emerging from the eggshell.

2. Red signifies our regeneration through the Blood of Jesus Christ—the Lamb of God Who replaced the annual animal sacrifices of the Old Testament that were offered in the Temple of Jerusalem, with His own perfect sacrifice.

At the court of Russian tsars and emperors, beginning from Alexey Mikhailovich (ruled 1645—1676), there was a special ceremony of celebrating Pascha, and its compulsory element was the distribution of Paschal eggs. His Majesty “would let everyone kiss his hand and presented all of them with colored eggs.” “They would hand out up to 37,000 eggs from Easter Sunday till Ascension Sunday,” the historian Ivan Zabelin wrote. At the court of Alexey Mikhailovich chicken, swan, goose, duck, and pigeon eggs, along with artificial wooden and bone eggs, were colored.

The Russian liturgical books prescribe the blessing of Paschal foods on the first day of Pascha, after the Paschal Liturgy just before the first meal after fasting. In practice, the blessing of these foods is performed on Holy Saturday. It is done for practical purposes—to suit the convenience of parishioners.

I would like to share a couple of other observations with the readers. While searching for and preparing the material for this article, I came across hundreds of superstitions associated with how one should cut kulich and pascha cheese “properly”, when and how we are supposed to eat them ”properly”, how to break eggs, and so on. Dear friends, you can cut kulich and pascha cheese and break eggs however you want. There is a pious tradition to start the festal meal after the Paschal Liturgy with Paschal dishes—the blessed kulichi, pascha cheese, and colored eggs, and to have them for breakfast throughout Bright Week.

It should also be noted that the liturgical books (the Typicon and the Book of Needs/Euchologion) mention the blessing of pascha cheese (“thickened milk”) as a kind of food the faithful abstained from for a spiritual purpose. They also mention meat as the kind of food that people shouldn’t bring to church for blessing, as not all food products are blessed in church.

In conclusion let us answer one more question: When did the tradition of baking kulichi and making pascha cheese for the Radiant Resurrection of Christ originate? As Hieromonk Job (Gumerov) wrote: “The custom of making sweet, tall, rich white bread (kulich) and sweet curd cheese in the shape of a four-sided pyramid (“thickened milk”) for this radiant festival originated not later than in the sixteenth century.” However, both Catholics and Protestants bake Easter cakes too, so it is very likely that the tradition had existed even before the schism of 1054, though we have found no written evidence to support this idea so far. It is also difficult to say from what time pascha cheese has been made in the shape of a truncated pyramid. But there is at least one piece of evidence indicating that this tradition existed in Russia in the early eighteenth century. There is a church in St. Petersburg, dedicated to the Holy Trinity and built in the mid-eighteenth century, which is popularly known as “kulich and pascha cheese” because the church itself imitates the form of kulich, and its bell-tower mimics pascha cheese.

“I heartily wish for all of you to meet and spend this great Christian feast of feasts in peace and spiritual comfort, good health and prosperity,” wrote Archimandrite John (Krestiankin).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hTslvudycRM

Om nom nom nom nom.