This story was told to me by a former employee of the Soviet Special Services. He spent his entire life abroad. Now he is retired and regularly goes to church, confesses, and communes. I have been communicating with this man for many years, but I never tire of marveling at his intelligence and surprising decency, so unusual for our times.

In 1988, a great anniversary was celebrated in Russia—the Millennium of the Baptism of Rus’. It would not be incorrect to say that this event was celebrated by the entire country. If not for the timely maturation of Perestroika, the celebration would have affected a very small number of the faithful of that time. Perestroika allowed us to talk about the Millennium of the Baptism throughout the entire country.

In June of the same year, there was a Local Church Council at which an event unique for the times took place—the glorification of nine new saints. It was unique because the last glorification before that took place in 1916. The Soviet authorities, who had vowed to organize communism in the country by the 1980s and show the people “the last priest,” absolutely could not allow any glorifications. After all, if new saints are glorified, that means the Church is alive.

Besides the delegates, members of foreign delegations were present at the Council, including representatives of the Catholic and Protestant churches. There was also a delegation of three people from one of the Scandinavian countries. Upon arrival, they were assigned a guide and translator from among, of course, the local KGB officers, who accompanied his charges everywhere. He was present with them at the sessions of the Council as well, which were held in the refectory of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra.

“I have known him all these years,” said the man who was telling me this story, “and now we are parishioners of the same Moscow church. This is how he came to faith.”

During the commission of the act of glorification, they brought large icons of the new saints into the room and placed them among those gathered for all to see.

From here, the narration continues from the guide-translator who was accompanying the Scandinavian delegation:

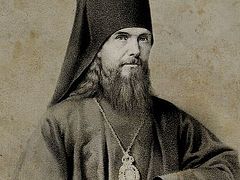

“One of the nine icons was set up directly across from us. The icon depicted an ascetic-looking monk in a klobuk with a Panagia on his chest. His right hand was raised in a blessing, and in his left he held a book. I didn’t know who it was, but looking closely, I read: ‘St. Theophan the Recluse.’

“Although the saint’s gaze was slightly off to the side, it still seemed to me that the monk was looking directly into my eyes from the icon. And no matter how I turned away from him, our eyes met again and again. I knew that there had been some priest and monks among my ancestors. I didn’t believe in God at that time—it was never an interesting topic for me; all the more so because a state security officer could only be compromised by such a relationship [with God—Trans.], so my family never had conversations on this topic.

“During a break, I asked my charges to tell me about St. Theophan.

“’Oh,’ one of them responded, ‘he was a remarkable ascetic, practically our contemporary, who chose the ancient podvig of reclusion’—and he told me more about him.

“After lunch, I looked again at the image of the saint, and knowing then about his life, I even imagined that my religious ancestors could have probably looked that way too. It would be interesting to see their faces. My grandmother was supposed to have left some old, pre-revolutionary photos behind. My mother probably knows something about them.

“In the evening, having returned home, I called my parents. My mom picked up the phone and I started asking her about our ancestors who were priests before the revolution, and I asked if there were any photographs of them.

“’I’m surprised at you,’ my mom responded. ‘You never cared about our ancestors before, and now today you’ve suddenly started asking about them. Come on, lay it all out; tell me what’s going on with you.’

“Then I told her about how I was at the Council in the Lavra and I had to spend the whole day looking at the image of St. Theophan, and about how I wanted, for whatever reason, to learn more about our ancestors. I spoke, and my mom was silent.

“’Mama, why aren’t you saying anything? Do you hear me?’

“’I hear you,’ my mother said, for some reason in a wavering voice, ‘and I can’t believe it, because you, son, are the great grandnephew of St. Theophan. It seems our holy ancestor found you himself and looked into your eyes all day long.’”