February in Georgia is already spring. The sun warms gently, birds are singing with all their might. We’re hurrying to the Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, in the center of Tbilisi near the Kura embankment. Archpriest Maxim Chanturia, the rector of the church, has agreed to speak with us, to tell us about how he came to faith, how he became a priest, and to share his recollections of the ascetics whom he has met on his life’s journey. This is his story.

“Life is vanity, and you have to think about God”

How did I come to God? I’ll tell you. I was born in 1968, in the godless times, when the authorities were persecuting the Church.

There were many sorrows and sad events in our family. Babushka was widowed early: My grandpa suddenly died in 1937 at the age of 37 from peritonitis. My father’s brothers, my uncles, who were very close to us, departed at 31 and 43. It was a great grief for our family.

In those years, all the churches were closed, but my parents always remained close to God in their deeds: They kept their consciences clean before the Lord and were very conscientious and wise people.

I learned two pieces of wisdom from my father. The first, he often said: “Life is vanity, and you have to think about God.” And then Papa wondered why his sons wanted to be come monks and priests [Fr. Maxim smiles].

Second—there was often a sadness in Papa’s eyes, caused by the memory of death. He knew that my mother was terminally ill.

Remembrance of death

Mother got sick when I was only four, and I didn’t understand what was going on with her then; when I grew up, I realized that Mama had cancer. They diagnosed her, but the disease developed slowly, as if the Lord was giving her time to raise her children—she had three sons. Mother lived with this disease for more than thirteen years, but she knew this whole time that she was terminally ill and would die young. I also knew this whole time that she was sick and dying.

I was afraid when the mailman would come to our house—maybe he was bringing news about her death. It’s very hard for me to teach my parishioners about the memory of death now—people constantly forget about it: The human soul knows it is eternal and does not believe in death. The evil one steals the memory of death. But Mama and Papa constantly lived with this memory, and with me—a young boy—it happened by itself.

What did I learn from my mother? Mother was sad sometimes: When she got sick, her friends and relatives forgot about her a bit. And she would sigh: “If someone becomes weak and feeble, no one needs him. No one—except God.” It was like she was telling us to be strong. The Psalter says: Put not your trust in princes, in sons of men, in whom there is no salvation (Ps. 145:3).

I often recall my mother’s eyes—something mysterious was conveyed in her look, in her calm and gentle disposition and her prayerful state of mind.

A disciple of holy elders

There were other circumstances. My grandfather’s cousin, Fr. Gregory, labored as a monk on Mt. Athos, in Iveron Monastery, which the Georgians founded in 980. Iveron ranks third among the twenty monasteries in the Athonite hierarchy and has many holy relics—more than any other monastery on Mt. Athos.

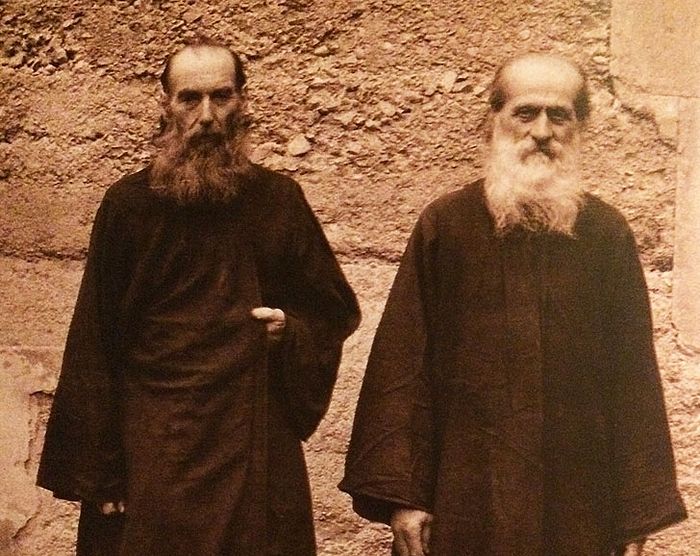

In 1924, the Greeks drove the Georgians off of Mt. Athos, accusing them of spying for the Russians. These Georgian fathers then lived in the monastery in Betania, among whom were the famous Betania elders Archimandrite George (Mkhiedze; in the schema—John) and Archimandrite John (Meisuradze), the spiritual fathers of St. Gabriel (Urgebadze).

My great uncle, Fr. Gregory, was well-known in Georgia; he was spiritually nourished by St. Alexei Shushania, an archimandrite of the Georgian Church, who reposed in the Lord in 1923. Fr. Gregory would often come to our house, and my papa knew him well. He would tell me about this ascetic, about how Fr. Gregory was a bright and grace-filled man, a hesychast, a prayer of the Jesus Prayer.

My grandfather was on the list of the dead

My other grandfather, Andrew (my older brother saw him alive, but not me, but I heard a lot about him) was educated in a seminary at a monastery in the city of Khobi. This monastery had the robe of the Most Holy Theotokos (now it is in the historical museum in the city of Zugdidi, near the Blachernae Church).

There were famous fathers laboring in the monastery, and the Righteous St. Ekvtime , the Man of God, would go there. Ekvtime (Takaishvili), an historian, archaeologist, and founder of museum works in Georgia, hid icons and other sacred objects from the soviet authorities, taking them to France. He lived in difficult circumstances in France. In 1931, his wife died from hunger, and Ekvtime himself was often on the brink of death from hunger and cold but did not sell any part of the national heritage and returned everything safely to his homeland in 1945.

He lived ninety years and again endured grief and persecution, living under house arrest until the end of his life. In 1963, the year of the 100th anniversary of his birth, his body was reburied, and it turned out that not just his body, but even his clothes and shoes had not decayed.

My grandfather Andrew didn’t manage to receive the monastic tonsure; he was a simple young layman. He was shot in 1924. They shot fifty people at that time, as opponents of the soviet government. They were troubled times. Prisoners were forced to dig their own graves, then they were thrown into them, and sometimes they weren’t even buried. By lucky chance, or rather, by the providence of God, two out of the fifty miraculously remained alive—one of them being my grandfather Andrew. He was in a state of shock. He was only 24, but he turned completely gray. He crawled out of the grave, where there was a pile of dead bodies, and hid in the woods for five years.

Then he was able to leave and go to his relatives and live in the world, but he never had any kind of documents and received no pension in his old age. Even his uncle, the Council Chairman, was unable to help get him his documents. It was as if my grandfather was already no longer on this earth—he was listed among those executed, on the list of the dead. He preserved the memory of death. Grandpa was often grieved: He endured with great pain the godlessness that reigned all around.

I never heard anything more compelling in my life!

My grandmother, Nadezhda Pavlovna, was semi-literate, having finished only elementary school before the revolution. Now I have among my relatives very educated people, professors, but we are all far from our semi-literate grandmother, who was wise and profound, and attained spiritual discernment.

Her life was full of woes: She was motherless from two years old, lost two sons to illness and three brothers in the First World War, and was widowed early.

She knew the Gospel, the prayers, and poems of the eighteenth-century spiritual poet David Guramishvili by heart. I well remember Grandma telling us children about how God created the world, about Moses, about the flood, about Noah’s ark… It was so compelling and impressive! I never heard anything more compelling in my life!

Babushka was one of the most influential people in my life. I graduated from the theological academy in Tbilisi, from graduate school in St. Petersburg, and defended my PhD, but I can say that all this education gave me fifty percent of my spiritual life, and the other fifty percent of my education and prayer life came from my babushka and parents…

If a person grows up godless, it’s difficult to then educate him… It’s hard to reeducate an adult…

Worldly success has lost all meaning for me

I served in the army in the Far East, and we would listen to a program from America, “Time of God.” They were very comforting stories for us. When I returned from the army, perestroika had just begun, and they began to preach the word of God more boldly. In 1988, I began to speak with priests and started to read religious books.

I went to college in Kutaisi, in the chemistry engineering department, and studied technology and catering. We young people saw ourselves as successful businessmen in the future, directors of restaurants… But this worldly success gradually lost all meaning.

I heard a homily in church; it was as if the priest was speaking just for me: “We don’t need to ask God for anything, only that He would grant faith, hope, and love.”

And I started to pray about it. I soon had the desire to enter the theological academy. In 1990, the Lord gave me a spiritual father. It was Fr. Mark, who is now Metropolitan Anthony (Bulikhiya). He blessed me to enter the spiritual academy in Kutaisi. I started, and after the first year I transferred to the theological academy in Tbilisi.

I taught the Law of God and the history of religion in rural schools on Saturdays in my fourth year, and I was full of joy when I taught children. I never thought I would become a teacher; my father worked as a teacher for fifty years.

Lord, tell me how to serve Thee

I turned 22, and I wavered about what to do: Should I become a monk, a priest, or a teacher (I really liked teaching children). Then a concrete thought came into my head: “How should I serve God?”

December 19, the feast of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker arrived. At that time, of the saints I knew the patrons of Georgia, the Equal-to-the-Apostles Nina and St. George, but about the Holy Hierarch Nicholas Wonderworker, I knew very little, although my parents had started their family on his day.

And on this day, I decided to especially pray to God about my question. My mother was no longer with us and my father and brother were away. I knelt before the icons, of which we only had a few, like everywhere in those years. One of the icons was my mother’s “She Who is Quick to Hear.”

And so I got on my knees and began to pray: “Lord, tell me how to serve Thee.”

I finished my prayer and felt confident that the Lord would reveal it to me. You know how a child cleans up his toys before sleep and goes to sleep with a sense of accomplishment? And I went to bed. I was lying there, and the saints from the icons were looking me in the face—the Most Holy Theotokos, St. George.

Then suddenly—I wasn’t sleeping yet—I clearly saw a man standing before me, not very old, 65-70, balding, in a riassa. I wasn’t sleeping yet; my eyes were open, still energetic after prayer. And he said three words to me: “Holiness, holiness, holiness.”

I realized this was the answer to my question, “How to serve God?”—“Serve God with a holy, pure life.”

This was no icon before me; it was a living manifestation. I didn’t feel any fear; quite the contrary, I felt cheerful and calm. He had very kind eyes, and in his look were courage and spiritual firmness.

In the morning I went to my spiritual father, Fr. Mark, who is now Metropolitan Anthony. At that time he was restoring the village church and had just made a new iconostasis there. He really didn’t like superstition, dreams, and visions. He would read St. Ignatius Brianchaninov and St. Theophan the Recluse to us about how we shouldn’t believe in dreams. I didn’t want to tell him about my vision—I was afraid he would scold me. But I couldn’t resist and went to see him anyways. And suddenly I saw my guest—on the icon next to the icon of the Most Holy Theotokos.

And I immediately blurted out, involuntarily: “Who is this saint?!”

My spiritual father was busy talking with some woman just then, and loudly repeated to her: “You must not believe in dreams, do not believe in dreams!”

He turned to me and answered my question: “It’s St. Nicholas the Wonderworker!”

And I blurted out: “He was at my place! He was at my place!”

My spiritual father didn’t understand and asked: “Who was?”

But I declined: “Ah, nothing…”

I told him the truth about fifteen years later.

St. Nicholas didn’t tell me at that time: “Become a monk or a priest.” He said: “Live a holy life.” And everyone who lives a holy life, who preserves his conscience unblemished, serves God and is a true servant of God.

I never saw St. Nicholas again after that—probably there was no need for it. But after St. Petersburg, I became the rector of the Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker in Narikalo, and now I am the rector of this church, also in honor of St. Nicholas. I feel that he is constantly helping me, but secretly—the saints love to do this. He secretly helps many; he secretly threw bags of gold to the three betrothed girls…

St. John Climacus says that the saints help us in secret. It’s like what parents do: They undress or dress a sleeping child, and he doesn’t see it.

The most important thing in life is to do the will of God

I have two brothers, and we are all priests, archpriests.

In my early twenties, I had a very vivid dream. Usually I don’t pay dreams any mind, but this was special, and I still remember it. In a subtle dreamy vision, I saw three large eight-pointed crosses, and a voice said: “Take your cross and go.”

It was a wonderful voice, and I realized that it wasn’t human, but Divine.

I took the third cross and immediately woke up. The vision made such a strong impression on me that I started asking monks about its meaning. One of them said: “We’ll see. No need to believe in dreams.”

At 25 years of age, they offered me, the first out of my brothers, to become a priest. I refused—I wanted to wait until the canonical age of 30. And I suffered a spiritual punishment: I lost my joy. It’s hard to explain: I studied, I confessed, I communed—all as usual, but I had no joy.

After graduating from the academy in Tbilisi, in 1996, I started postgraduate studies as a scholar at the St. Petersburg Theological Academy. I defended my thesis and returned to Georgia.

In 1998, when I turned 30, His Holiness Patriarch Ilia II ordained me as a deacon. Only when I was ordained did my joy return to me. Then I realized that it had been a spiritual punishment for disobeying the will of God.

Then they ordained my older brother as a priest. In 1999, His Holiness ordained me as a priest too and sent me again from Tbilisi to St. Petersburg, to the Georgian parish, where I served in the Church of the Shestovsky Icon of the Mother of God for three years and taught Sunday School.

When my older brother and I both became priests, then I understood what my dream had been about. When they were planning to ordain our middle brother, his wife and her relatives opposed it, and their daughter became very sick. Nefrit was dying. I had just returned from St. Petersburg and told them my dream. I told my brother about the priesthood: It’s a Divine calling and you mustn’t go against the will of God.

I’m nearly 50 now, and I have realized that the most important thing in life is to do the will of God. How do we learn His will, you ask? I think if we live according to conscience, if we are sincere, the Lord will reveal His will to us. He can do this through a spiritual father or through life circumstances, or some other way. The main thing is to live according to conscience.

Our church

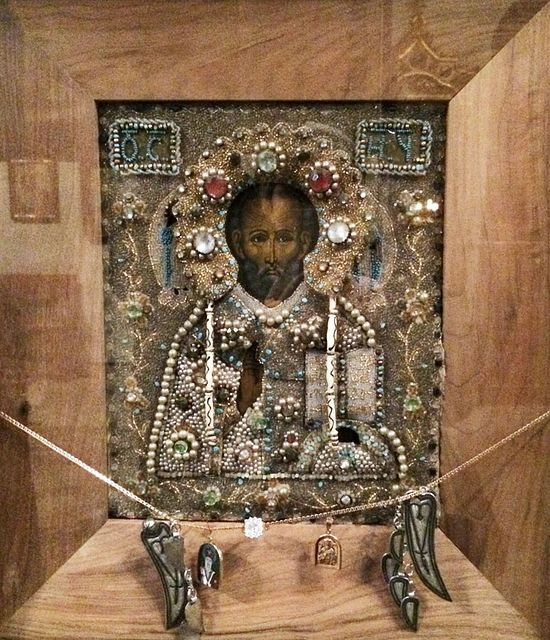

The church where I serve and labor as the rector now is very ancient. It was destroyed and restored 175 years ago. It was consecrated in honor of the Elevation of the Precious Wood of the Cross of the Lord. 150 year ago, it was renamed in honor of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker. We have a revered ancient icon of St. Nicholas.

The publishing house “New Iveron” operates at our church. I am its founder and head. There is also a Sunday School, an iconography workshop, and the children are taught handicrafts. Many young people come here; they sing on the kliros and even celebrate their name days here.

Remember: God sends us good people

Last year one of my students told me: “Fr. Maxim, one author says: ‘Our life is one big surprise.’”

I really liked this thought. I thought about how an even greater surprise awaits us in the next life.

The biggest miracle for me is to meet good people. When I met my spiritual father, Archpriest John (Mironov), twenty years ago, he said to me: “Fr. Maxim, remember: God sends us good people.”

These words of his are enough for me, even if he hadn’t taught me anything else. I only need to keep my eyes open to see the good people sent by God.

We communicate with God through people. We receive Divine grace through the Sacraments, prayer, and through people. It’s one of the meanings of the Incarnation—because the grace of God is embodied in God’s people.

My first spiritual guides

In my life, I have met highly spiritual people who have had a great influence on me. My first spiritual guide was Fr. Mark, now Metropolitan Anthony. He was named for the Evangelist Mark, and he explained and preached the Gospel to us young people in an accessible language. He enlightened us. He was a courageous shepherd and a hospitable man. Communicating with him, we were full of joy. He taught us to be vigilant and careful so as not to fall into spiritual delusion.

I also consider Archimandrite Nicholas (Pitnava) one of my spiritual mentors, whom I met later. He was an ascetic, a great faster and man of prayer. He possessed great spiritual intuition. I was drawn to him by the sanctity of his life. He was the first from whom I felt a fatherly love—and I had great trust in him.

Unceasing prayer attracts such grace from God!

After almost thirty years, I always have this regret: Why did the Lord close the monastic path for me, and I didn’t think about becoming a monk?

When I moved to Tbilisi, Archimandrite Raphael (Karelin) made a great impression upon me. He taught us asceticism, and after meeting him, I learned the ideal of the monastic life, the value of ceaseless prayer. Now I teach asceticism and Church history in the theological seminary and academy in Tbilisi, but Fr. Raphael was a true theologian. When we were together at a service and he would go out to preach, it was unforgettable.

He wasn’t like Fr. Mark or the other spiritual fathers I’ve met in my life. He kept a distance; there was always a barrier between him and his interlocutor. I think it’s because Archimandrite Raphael had the ceaseless Jesus Prayer. I felt it when I met him. Men of prayer don’t say unnecessary words; they uphold prayer and cut off whatever distracts them from prayer—to protect their treasure. But this unceasing prayer attracts so much of the grace of God to them!

I never again heard such brief and pertinent answers to various spiritual questions as Fr. Raphael gave during his lectures!

I feel the spirit of grace

My main spiritual father is Archpriest John Mironov, a spiritual child of St. Seraphim of Vyritsa. Fr. John serves in St. Petersburg, in the Church of the Inexhaustible Cup Icon of the Most Holy Theotokos. My meetings with Batiushka were some of the best in my life.

He was different from all my other spiritual mentors—he wasn’t a theologian like Fr. Raphael, or an ascetic like Fr. Nikolai. Each father had his own spiritual gifts. Fr. John’s main gift, it seemed to me, was the grace of love—simple speeches and sermons, words, and actions, full of grace and love. I felt that he was the heir of some spiritual school. He covered everyone with his love, like his spiritual patron, St. John the Merciful.

I have never felt such love from anyone, rejecting no one. He healed our spiritual ailments with his joyful eyes, his sweetness, and his grace-filled words.

These people, my spiritual guides, as if gave me to taste the Orthodox spirit, and I can now recognize other grace-filled people. I feel the spirit of grace.

In the flow of God’s mercy

When I condemn someone or become bitter, I am not standing in the flow of God’s mercy; I make myself far from Him. Then I immediately try to change my thoughts.

When I desire good things for everyone and condemn no one, then I feel how the mercy of God flows to me.

I wish that all the readers of OrthoChristian.com would ever be in the flow of the mercy of God!

Fr. Maxim invited me to go to the hall where the youth were celebrating the name day of one of the young parishioners. I had to see how they love and respect their spiritual guide, how touchingly they anticipate every desire of their beloved Batiushka, how attentively they listen to his instructions. The youth barely speak Russian. I was warned that people over 40 speak Russia, but the youth no longer know it; that it’s better to speak with them in English. I switch to English, but they smile sheepishly: They know English about as well as our students from a regular school.

But Batiushka himself introduced me, and the young Georgians looked trustfully, joyfully, smiling at me. They sang Georgian songs for me. I listened and recalled the words of Fr. Maxim: “For me, St. Petersburg and Moscow are my native cities. St. Petersburg helped me acquire many friends, to get acquainted with Russian culture, with my spiritual father. Moscow gave me strength and courage.”

And I thought: As long as people like Fr. Maxim are alive, no politicians will be able to convince ordinary people that Georgians and Russians are enemies. As long as his generation is alive, we remember how we were family. And I can go to Tbilisi and know that true friends will meet me there.