Part 1: The components of “gerondism”

Orthodox theological critique of “gerondism”

1. Exclusivist (isolationist) trends.

In the history of the Church, these tendencies first manifested themselves in the age of the apostles. Thus, Apostle Paul in his Epistle to the Church of Corinth touches upon this phenomenon and rejects it by his apostolic authority: Now this I say, that every one of you saith, I am of Paul; and I of Apollos; and I of Cephas; and I of Christ. Is Christ divided? was Paul crucified for you? (1 Cor. 1:12-13); For ye are yet carnal: for whereas there is among you envying, and strife, and divisions, are ye not carnal, and walk as men? For while one saith, I am of Paul; and another, I am of Apollos; are ye not carnal? Who then is Paul, and who is Apollos, but ministers by whom ye believed, even as the Lord gave to every man? I have planted, Apollos watered; but God gave the increase. So then neither is he that planteth any thing, neither he that watereth; but God that giveth the increase (1 Cor. 3:3-7).

The critique by the great apostle to the gentiles boils down to three points:

a. Exclusivist (isolationist) tendencies in the Church cannot be justified, as they cause divisions in the Body of Christ. Besides, they are a soteriological error, for Christ the Savior is replaced by a man (even if he is an apostle of Christ).

b. Isolationist tendencies make Christian religiosity material and anthropocentric by nature. In this case, it is no different from the religiosity of other religious movements, founded by mortal people who are idolized by their adepts.

c. Exclusivist trends are an ecclesiological error as they contradict the basic Biblical teaching, according to which the Church is a work of the Holy Spirit and not a result of human efforts.

Later the phenomenon of exclusiveness was revealed as a separate choice by the devotees of certain saints, when Christians of the early period split into three groups: the admirers of St. John Chrysostom, called “Johannites”, made up the first group; the second group consisted of supporters of St. Gregory the Theologian, called “Gregorites”; and the third group was formed by the “Basilites”, who stood for St. Basil the Great’s cause. This split of the Church flock into three groups was healed by the Church itself through St. John Mauropous (the eleventh century), who instituted a feast day commemorating the Three Holy Hierarchs in common—January 30/February 12—after they had appeared to him in a vision and confirmed that there were no divisions among them and they were equal before God. St. John Mauropous composed a service to the Three Holy Hierarchs, one troparion from which reads:

“There is no repetition in these three, for each bears the seniority: none is first, there is a surpassing equality of honor; moreover they most joyfully credit the victory to one another, for the boldness of jealousy, which corrupts unanimity, has no place here” (Ode IX).

Choosing and cleaving to one and only one saint by the faithful is not a true component of Orthodox spirituality. Orthodox spirituality includes life, experience (empiricism) and the teaching of all the saints, and Orthodox piety is experienced “together with all the saints” (cf.: “With all the saints, let us commend ourselves and one another and our whole life to Christ our God”—from the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom). Even at a theological level the theological views of one individual Holy Father cannot be recognized by the Church unless they are shared by a majority of the Holy Fathers (the principle of Consensus Patrum).

The Orthodox Church has and honors the memory of a host of saints, but it exercises great caution as to the expression of its honor to them: Honor towards saints only means “veneration” and not “worship” (or “adoration”) because “worship” is to be offered to God the Trinity alone. It is significant that in troparia to saints, “glory” (that is, worshipful praise) is rendered to Christ and not to saints:

“Glory to Christ Who has glorified you”, “Glory to Him Who works miracles in you”, “Glory to Him Who through you works healings for all.”

If the Church is so cautious in recognizing the holiness of some of its members, then it is totally unacceptable for individual believers to hurry and “hand over holiness certificates” to their spiritual fathers, who have not been officially recognized by the Church, even though they may have been pious and devout.

2. The absolutization of the personality of spiritual fathers is also dangerous in that it is an infringement of the Christocentric nature of Orthodox spirituality. In this case, the one and only Truth of Christ is encroached upon and the Orthodox faith and piety are distorted by some elements of Protestantism. It was Protestantism that, proclaiming the individual (“personal”) nature of faith and piety, largely contributed to the split of Western Christianity into myriads of religious communities, each having its unique specifics in respect of doctrine and worship.

The absolutization of the personality of spiritual fathers can also reduce Orthodoxy to various forms of Eastern religions, when a spiritual father acts as a guru. The main distinctive characteristics of a guru are the following: a guru is regarded as a god-like figure, whose absolute authority is recognized by his followers; for his adepts, a guru is an object of worship, celebration, prayer and self-sacrifice. Thus Christianity is belittled, since every guru is considered an avatar, a prophet, and a “messiah”, while Christ is considered to be one of numerous avatars1.

Search for exclusively “charismatic elders” (“visionaries”) for confession and spiritual support is a depreciation of the sacrament of the priesthood, for repentance (confession) is a Church sacrament that is not dependent on the charisma of clairvoyance; it is truly performed by ordained priests who have been appointed as father-confessors2. The faithful should understand the following very clearly: Clairvoyance is one charisma, and priesthood is another charisma. The gift of clairvoyance is a very rare one, while priesthood is a common charisma which is available to all the faithful of all ages. Therefore, the faithful should not mix up these two phenomena, but they should obey the Church canons and decrees.

3. As for the publication of such books as, “The Life and Deeds of…” (certain spiritual fathers), they are probably acceptable, provided their aim is to collect the material and prepare the ground for the canonization of these fathers by the Church. However, if the publication of biographies of this kind doesn’t set such lofty goals, if it is done just as an expression of honor, respect and appreciation of the virtues of these spiritual fathers, then the following question arises: why do their authors only write the biographies of spiritual fathers, clerics and monks, but not of physical fathers and mothers who lived in holiness, or of other simple and nameless faithful3? In this sense, publication of the biographies exclusively of clerics and monks should necessarily be limited as intolerable one-sidedness.

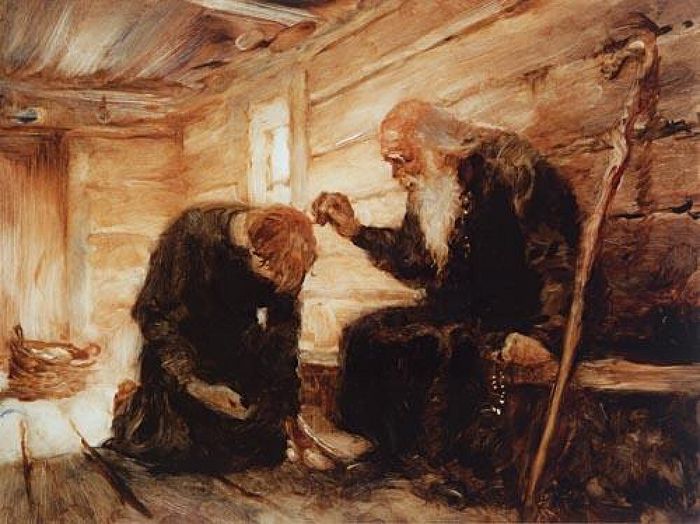

The ethics of a spiritual father and his child

However, understanding and diagnosing the phenomenon of “gerondism” is not enough. We should also highlight some of the main points that father-confessors with the charisma of spiritual fatherhood and their spiritual children should take into account.

The ethics of a spiritual father

A married or celibate priest who realizes that he has reached the age of maturity, attained spiritual maturity, and acquired a gift of the Holy Spirit, should take into consideration the following basic principles of ethics of a spiritual father.

a. You should exclude the possibility of focusing on your own person. The institution of spiritual fatherhood was established in the Church as a means for model dedication of the faithful to the life in Christ. A priest who possesses this charisma is called to unite the faithful with Christ and guide them to the life of the Church and not cultivate in people an attachment to their own person. Concentration on your own person (with the God-given gift of spiritual fatherhood) is a very serious and absurd error, because in such a case a man (one member of the Church) dares to replace Christ (the fullness of the Church Body) with himself. Spiritual fatherhood for someone’s own benefit may have as its object that priest’s promotion, gaining influence, personal enrichment, and in the worst cases—sexual harassment or exploitation.

b. You should not make adepts. Spiritual fatherhood develops a bond between the personality of the spiritual father and those of one or more believers in some way or another. Spiritual fatherhood is bad when the pastor takes advantage of this bond in order to make members of the Church become his adepts. An adept, or adherent, is someone who supports one or another individual, or group, or association, or political party, while rejecting all other people or groups, or opposing them. Adherents of various groups tend to oppose others to themselves and “fight” against each other. It is also typical of adepts to be fanatics. These devotees, directed and driven by the same personality, become fanatics and come to violence and criminal behavior. Let us recall that Christ fell victim to the fanaticism of adepts of some Jewish leaders: But the chief priests and elders persuaded the multitude that they should ask Barabbas, and destroy Jesus (Mt. 27:20). When a priest makes adepts, he loses the gift of spiritual fatherhood and becomes a mere party leader.

c. You should beware of one-sidedness. A spiritual father should avoid one-sidedness. The point is that sometimes spiritual fathers are obsessed by a one-sided vision or assessment of the situation. In this case it is wrong that the spiritual father’s one-sidedness is communicated to his spiritual children and is characteristic of them. As we have stated above, the most widespread kind of one-sidedness of spiritual fathers is the absolutization of ascetic monasticism4. Since the spiritual father (a hieromonk or a married priest) is too much taken up with monasticism, he communicates his personal preferences to those in his spiritual care. But an Orthodox spiritual guide is called to be “catholic”—that is, whole, and not one-sided, and present “καθ' όλον”—that is, according to all, the “catholicity” of our faith, and not special cases to his spiritual children.

The ethics of a spiritual child

Spiritual children who make use of spiritual fatherhood ought on their own part to take into serious consideration, and know the main principles of, spiritual childhood. As St. Simeon the New Theologian said, we ought to be wary—we must not stay in isolation, otherwise we will either be in danger of being eaten by the beast—the soul-destroying wolf, the devil—or we will fall and will have no one to help us rise to our feet. According to the Book of Ecclesiastes: Woe to him that is alone when he falleth; for he hath not another to help him up (Eccles. 4:10). We must not follow a wolf or an inexperienced doctor instead of a shepherd because of our imprudence (XX Catechetical Homily).

Some of the principles of being a spiritual child are as follows.

a. You should discern between guidance and dependence. An acquaintance and connection with your spiritual father are guidance and not dependence by nature. The spiritual father has received the charisma from the Church and the precept to guide the faithful to the freedom in Christ and not make them dependent on his personal fixed opinions and enslave them. So many things enslave people in our days! The spiritual instructor is called to set the faithful free and deliver them from the bondage of all that makes them slaves. Apostle Paul exclaims: Stand fast therefore in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free, and be not entangled again with the yoke of bondage (Gal. 5:1).

“The purpose of spiritual fatherhood is not the permanent dependence of the children on their spiritual father but assisting them in gradually attaining their spiritual freedom. A true spiritual father does not condemn his spiritual children to lifelong spiritual infancy; rather, he continually struggles so that they can mature—come… unto a perfect man, unto the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ (Eph. 4:13)5.”

b. You should distinguish between the charisma and the man. A believer establishes contact and communicates with a spiritual father not so much because of what a priest is as because of what he has. In other words, what matters in the institution of spiritual fatherhood is the charisma and not the personality of a cleric who possesses this charisma. What connects the faithful with a spiritual father is not the priest’s personality but the gift of the priesthood that he has received from the Church.

The charisma of spiritual fatherhood should not lead to personality cults; its mission is to connect the faithful with Christ, making them living members of the Church—the Body of Christ. According to Metropolitan Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia:

“In reality, the relationship is not two-sided but triangular, for in addition to the geronda and his disciple there is also a third Partner, God. Our Lord insisted that we should call no man ‘father,’ for we have only one Father, Who is in Heaven (cf. Mt. 13:8-10). The elder is not an infallible judge or a final court of appeal, but a fellow-servant of the living God; not a dictator, but a guide and companion on the way. The only true ‘spiritual Director,’ in the fullest sense of the word, is the Holy Spirit.6”

c. You should distinguish a monk from a Christian living in the world. We have already talked about the numerous and diverse God-given gifts of the Holy Spirit7. But efforts should be made for us to respect and appreciate both the charismas of someone else and our own gifts; and above all else we should not mix up different charismas. The gift of the monastic (and, especially, ascetic) life and obedience is one thing, and the charisma of the life in the world is another thing. The monastic obedience and the obedience of laypeople to their spiritual fathers should not be confused. Monastic obedience and that of laypeople vary in their extent and duration. Therefore, a spiritual father has no right to demand of his spiritual child an obedience similar to that which a geronda demands of his novice monk, and a spiritual child should not show him such obedience. A monk is obliged to obey “to his death”, and this commitment springs from the monastic vows taken during the monastic tonsure. Apostle Paul writes very clearly: But every man hath his proper gift of God, one after this manner, and another after that (1 Cor. 7:7). While a monastic vocation is a better path, the life and witness to Christ in the world is just as much a path to salvation.

d. You should choose a good spiritual father carefully. Let your elder be a spiritual person, with virtues, and preferably a practical man and not just a teacher. It would be good if from a “cabin boy” he develops into a “captain” and does not impose his monastic “experience” (that he has learned from books) on the backs of others. Or let him have great love with prudence from birth so that his heart might ache for his children and might not wish to send them to Paradise using the methods of Diocletian… It would also be very good if the geronda were at least eighteen to twenty years older than his spiritual child, because in this case the child naturally respects the pastor. An elder should live a simple life, without worldly cares and unnecessary fuss; nor should he push forward his personal advantages, but should pursue the advantages of his spiritual child’s soul and of the Mother Church.