Ivan Petrovich Zhukovsky “How have you not heard of Blessed Ivan Petrovich, the fool for Christ?!

Ivan Petrovich Zhukovsky “How have you not heard of Blessed Ivan Petrovich, the fool for Christ?!

“I heard something… I only recently started going to church…”

“What’s the difference?! All of Odessa knows him!”

I heard such a conversation about the blessed Elder Ivan Petrovich Zhukovsky, a fool for Christ—who labored here until the Khrushchev times—between two parishioners at the podvoriye of the Odessa Archangel Michael Monastery, located on the ancient Dormition Street, not far from the seaside Park Langeron.

My wife and I went there on pilgrimage and learned many interesting things.

In the monastery

The monastery was founded more than 160 years ago by the royal Vorontsov couple—the hero of the War of 1812 Mikhail Semenovich—Governor-General of Odessa, and Elizabeth Ksaverevna, with the participation of the favorite lady-in-waiting of Empress Elizabeth Alekseevna the countess Roxanne Edling, and other patrons. In the godless twentieth century, the monastery was closed several times, in the 1920s and the 1960s—the years of the Khrushchev “thaw”…

Archangel Michael Monastery today, view from above

Archangel Michael Monastery today, view from above

The monastery was rebuilt literally from ruins and from the remains of the former monastery buildings in 1991, on the site of the then-still functioning tuberculosis clinic by the labors of the indefatigable Abbess Seraphima (Shevchik) and the sisters. Matushka managed not only to restore the traditions of charity and build a hospice for the elderly, but also to create a branch of the women’s department of the Odessa Theological Seminary. Although only a small part of the once-vast territory of the monastery, which took up an entire city block, was returned, it accommodated churches, a pilgrims’ hospital, monastic buildings, an almshouse, a museum of Christian Odessa, an old folks’ home, and the women’s department of the Odessa Seminary. In the seminary, the girls learned iconography, gold embroidery, choir directing, and to be Sisters of Mercy and housewives.

All of this was foreseen and spoken about by Blessed Ivan Petrovich Zhukovsky, a clairvoyant podvizhnik and wonderworker who hid his spiritual gifts under the guise of foolishness, and lived in the stables there after the war, bearing obedience in the small trapeza for pilgrims and parishioners until his repose on March 28, 1960.

At the old Christian cemetery

St. Dimitry Church at the Second Odessa Cemetery “You absolutely have to go to his grave, at the Second Odessa Cemetery,” an elderly, talkative parishioner said in a sweet Odessa dialect, turning to us, having heard that we had arrived from Kiev. “You’ll see many interesting things there, such that you’ll want to go there many more times… You won’t regret it…”

St. Dimitry Church at the Second Odessa Cemetery “You absolutely have to go to his grave, at the Second Odessa Cemetery,” an elderly, talkative parishioner said in a sweet Odessa dialect, turning to us, having heard that we had arrived from Kiev. “You’ll see many interesting things there, such that you’ll want to go there many more times… You won’t regret it…”

We went to the monastery, which is a fifteen-minute tram ride from the famous Odessa market. The central cemetery lane led us to an old church named for St. Dimitry of Rostov—the only one in the city, which was closed several times in the twentieth century. Along the way, we passed the old tombs and alleys of the defenders and liberators of Odessa during World War II—soldiers, officers, generals, and admirals—and also the “alley of widows,” where the “graves” of sailors who died at sea can be found.

To the right of the church is the grave of the outstanding ophthalmologist Vladimir Petrovich Philatov—an Orthodox Christian, spiritual friend of Patriarch Alexei I (Simansky), and co-struggler with St. Luke (Voino-Yasenetsky), with whom he maintained a spiritual correspondence for many years. A little further, along the south alley, is the so-called “priests’ quarter,” where rest the remains of the city clergy, monastics, choir directors, rectors, and teachers of the Odessa Seminary.

The grave of the blessed Elder Ivan Petrovich Zhukovsky with a stone cross is located near the southern alley. His gravestone reads: “He lived, for Thou didst create him. He died, for Thou didst call him.”

At the elder’s grave As the handmaiden of God Natalia Ivanovna, who feeds the pigeons at the graves, explained to us, it’s the most visited place, with people coming every day, including pilgrims from all throughout Ukraine, from abroad, and even from the U.S., where Odessans who emigrated from the USSR carried the memory of the blessed wonderworking elder. Now they come here from America, to ask for the prayers of Blessed Ivan.

At the elder’s grave As the handmaiden of God Natalia Ivanovna, who feeds the pigeons at the graves, explained to us, it’s the most visited place, with people coming every day, including pilgrims from all throughout Ukraine, from abroad, and even from the U.S., where Odessans who emigrated from the USSR carried the memory of the blessed wonderworking elder. Now they come here from America, to ask for the prayers of Blessed Ivan.

“I was very sick,” the woman said, “incurably, you might say. I started going to Ivan’s grave. They regularly serve molebens here, and there are processions. I asked the blessed one for help. By the grace of God, I’m alive; God extended my life for repentance and prayer. I come here often. He’s a great saint, although he’s not yet canonized… There are people still living who knew him. St. Michael’s Monastery has a Mother Arsenia, a schemanun, who could tell you many interesting things about Ivan Petrovich…”

“He wept for people, and his tears would turn to ice in winter…”

With the blessing of Abbess Seraphima, we found the 88-year-old Schemanun Arsenia in the monastery, who truly turned out to be an interesting storyteller. And the main thing is that she is a living witness to the Church history of the twentieth century. Before speaking about the blessed Elder, Matushka told us about herself, about her path to the monastery.

Schemanun Arsenia:

My parents were simple people; workers in the Oryol Governorate. The whole family lived in a farmhouse. When the law on collectivization came out, it was said that no one would live separately, then we moved to the Kaluga Province, to the city of Maloyaroslavets. Two of my sisters are still living there. There were eight children in our family. Mama was illiterate and would say, “I want all my children to learn.” The times were tough when my father returned from the war after being wounded. The Germans blew up our house as they were retreating, and we literally lived on the streets. But the soviet soldiers warmed us up, gave us temporary housing, and fed us. The Chernoostrovsky-St. Nicholas Monastery was near us, where the whole family would go. It was evident that the seeds of future monasticism were sown there. The Chernoostrovsky Monastery still exists. Two of my sisters live at the monastery—thus the Lord arranged. One of them worked at the bread factory and was given a room. The abbess said to her, “Live here until you die.”

My whole family loved the Church. There was a little church on the hill in my childhood. Sometimes my mother would tie red scarves on her head and say, “These are my maiden scarves; you wear them now,” and four or five of us would run to church, to Batiushka.

Batiushka would pat us all on the head, pity us, and say, so that mama and papa could hear, that we were well-behaved in school. Batiushka often visited us at home. Monastics who used to live in Moscow also stayed at our house a lot. At that time, they considered all believers, especially monks, to be enemies of the people and sent them to the 101st kilometer, where our Maloyaroslavets was located. Thus, it was easy to meet the inhabitants of various monasteries in our town. As a rule, they stuck together and tried to live in communities. We also always had many members of the intelligentsia: teachers and professors who had been sent to our city. We really loved them, and they loved us and helped us with our studies.

There’s a legend that when the German troops were 30-40 miles from Moscow, Stalin didn’t know what to do, and turned to a crippled clairvoyant, Matronushka, who is now one of the most famous and revered saints (I always pray to her to heal my eyes). They say that they took her to Stalin himself, and he asked her what to do—to leave Moscow or stay. She put her hand on his shoulder and said, “Don’t leave, the red rooster will win—but you have to open all the churches.” That’s what the people say, but how it really was, God knows…

But then we saw how our church in Maloyaroslavets, which was used as a grain warehouse, suddenly opened. In one day, Stalin gave the order, and Church life began to revive. They sent us a batiushka who had spent many years in exile, Fr. Vasily Mashkov, and he served with us for many years. What great joy, what a triumph! Everyone, adults and children, went to church and helped Batiushka however they could. When Batiushka would read commemoration lists, he would cover them with tears, because there were many names that he knew from exile and who were imprisoned or in camps. He talked a lot about that period of his life. His matushka died early and he raised his daughter himself, whom he greatly pitied. My parents greatly revered Fr. Vasily, and he often came to our house, and we knew him well. They buried him there in Maloyaroslavets.

All of my brothers and sisters finished tenth grade and went to study in Kaluga. My family had seven girls and two boys. One became a teacher, another a doctor, my brother Sergei became a pilot, and Peter took the tonsure and became Monk Pimen; he has spent many years in the Holy Dormition Monastery in Odessa…

When I worked in Moscow, I found out that there was a convent in Odessa (it wasn’t very easy to find the address of active monasteries then). So at twenty-two years old, I went to Odessa and went to Mother Anatolia to ask to enter the monastery. She said to me, “No, my daughter, go back to Moscow. You don’t have a residency permit, and I can’t take you without it. Go back and work some more.” I was in tears. I burst into tears, lamenting that I didn’t want to go to Moscow and didn’t want to work in the world anymore.

Ivan Petrovich, a great servant of God, a saint now revered by everyone, then a fool for Christ, was living in the monastery. He apparently saw me crying and sent a nun to calm me down. This nun approached me and said, “Ivan Petrovich said you should calm down, because although the abbess did not receive you now, the Mother of God has already received you.”

Exactly a year later, they sent me a letter saying I should go to the monastery with my belongings. What a joy it was! I was so warmly and tearfully accompanied by my whole family… Then a second sister arrived at the monastery, who worked in a school, then a third. And then, after the army, Peter came and entered a monastery.

Ivan was small of stature, had a small beard, and was very noble. He was a fiery pillar of prayer, a God-pleaser. The sisters and I were so happy to meet with him, to talk, and sometimes weep. And he would listen and say, “A little big for your britches,” and keep walking… Or he would say: “You know, my child, when dough is kneaded and beaten for a long time, it makes good bread.” And sometimes he would simply say: “Go with God! Go, my child…”

We lived like this for eight years. He nourished us all. And the food was good. Sometimes he would knock on our door. “Who’s there?” “Ivan. Do you want some oatmeal?”

They fed us well. The monastery had its own mill—our breadwinner; we worked there day and night. We sometimes ground twenty tons of grain in a night… What bread we baked! Our mill was famous, and many came because of it. There were gardens. Everyone worked.

Once Ivan knocked on my window and asked the time. I told him it was 2:30. The thing is that it was a winter night and everything was covered with snow. I saw little icicles hanging on his cheeks under his eyes—it seems he had been weeping and his tears froze. Like a rabbit, he walked through the soft snow barefoot, and I watched him go… I still have this picture before my eyes. That’s how Ivan Petrovich was.

His cell was on the side of the gate. We had many young people then—forty people. We would walk around the monastery, singing Psalms. We didn’t want to sleep, although the services were long. Someone would say, “Let’s go look through Ivan’s window, to see what he’s doing.” We would see him kneeling, praying to God…

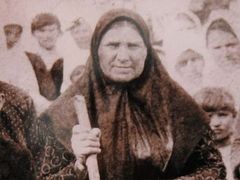

The sisters of the Archangel Michael Monastery, late 1950s

The sisters of the Archangel Michael Monastery, late 1950s

Earlier, the Akathist to the Archangel Michael was read in the evening. After the service, Ivan would set the table and feed all the pilgrims and poor people.

Once a woman complained to Ivan that her husband was seeing another woman. Ivan said, “Bring your husband here.” She brought him. Ivan turned to him and said, “Bridegroom, come here.” And that turned out to be enough: He didn’t cheat on her anymore.

Priests often came and waited for him until late at night just to take his blessing.

And the miracles! A seminarian who had just been ordained as priest was coming. He was walking and thinking, “If Ivan Petrovich comes up to me and takes my blessing, then I’m a real priest.” He had only just thought it when Ivan Petrovich stopped working and approached him for a blessing.

There was another time when one of the parishioners started to complain that he was cramped and needed to apply for an expansion of living space. Ivan went up to him and began to arrange some small boards in the shape of a long box, saying, “Expansion, expansion…” That man died within a few days.

When they had Ivan Petrovich’s funeral, all of Odessa came; all transportation stopped. Policemen came and asked about him—who he was, that the whole city knew about him. But at that time it was impossible to say that he was a servant of God; belief in God was persecuted then, therefore we answered that he was a very kind old man and loved and helped everyone.

But the police had come to the monastery once to see this grandpa and asked to see his identification documents. He grabbed a pack of commemoration lists lying on the table near the icon shop, threw them in the air and said, “Here’re my documents, here’re my documents!”

I lived with his cell attendant Mother Leonida for fifty years. She was buried not far from Ivan. She would hold the Psalter in her hand just to turn the pages, because she had the kathismas memorized; and when people would ask her, amazed, how it happened, she would answer: “Sunny,” (as she called Ivan Petrovich) “gave me such intelligence that I could pray from memory.”

He helped us and still helps us now—such a great servant of God we had living with us. He was born near Odessa in the village of Nerubaiskoe, graduated from seminary, and was the diocesan secretary. Then he went to see Fr. Jonah Atamansky, now glorified among the saints, and spent a week with him. Batiushka Jonah saw with his spiritual eyes that he would not receive Holy Orders but would be a fool for Christ. There are many saints, but you can count the fools for Christ on your fingers. He went to see him all dressed up, with a white bowtie, but left him with a bag slung over his shoulder, and went to the church where his brother was the priest. He really loved his brother. He spent many years as a fool for Christ, living in the cemetery, sleeping on graves, and then he came to us.

And then he died, and they buried him at the Second Odessa Cemetery, on the monastery plot. He is lying in the ground now, but his soul is with the Lord—and he helps and will continue to help everyone.

“He was a light of spirituality in the most difficult years of the Church of Christ’s existence in Odessa”

The story about Blessed Ivan is continued by Mother Seraphim:

Ivan Petrovich Zhukovsky was an amazing man who lived during the most difficult years of the Church of Christ’s existence in Odessa, supporting the faithful and the sisters of this monastery. He was a light of spirituality. Although he seemed like nothing much on the surface, he was very modest and very hardworking, and was probably the humblest of all believers in Odessa at that time. He lived in the Second Odessa Cemetery during the war and went to the Church of St. Dimitry of Rostov at this cemetery—the only one that had been preserved at that time. Then he moved to our skete at the eighth station in the Big Fountain section of Odessa. When the soviet authorities closed the skete in 1945, he moved to our monastery on Dormition Street. The sisters really loved him and remember him with special reverence. There are very many testimonies of miracles that he performed, and testimonies of his extraordinary clairvoyance and grace-filled prayer.

Ivan Petrovich Zhukovsky was born in a priestly family. He graduated from the Odessa Seminary and worked as the diocesan secretary. According to some reports he was ordained as a priest, but no one remembers him as a serving priest; they remember him only in the guise of a fool. He always wore the same clothes, winter and summer, self-made from coarse canvas. Out of the wide-open collar of his shirt peeked a cross on a simple cord. In the winter he sometimes also wore a coat, old and patched. He went about barefoot in any weather.

Ivan lived in the monastery stables. He had the obedience of feeding the elderly and parishioners in the small trapeza. He treated all who came with love, seeing the sorrows and maladies in their lives, and by his mysterious, periphrastic words and actions, he would help them endure their grief, comfort and strengthen them; and he foretold the future.

Ivan lived in extreme poverty but did not tolerate uncleanness. He always had a broom and dustpan in his hands. There were times where he swept the floor especially carefully. “Look how he’s sweeping,” the sisters would say. “It means Vladyka is coming soon.” And so it happened.

The blessed elder possessed the gift of healing—in this was manifested his special love for people.

Panikhida and moleben at the blessed Elder’s grave

Panikhida and moleben at the blessed Elder’s grave

The Elder’s prayer was complete communion with God. Some of the sisters were vouchsafed to see him during prayer—in tears and concentration.

We always pray for his repose because he isn’t glorified as a saint yet. We pray to God for the repose of his soul; we go to his grave on January 20, the day after Theophany, the day of the commemoration of the Synaxis of St. John the Baptist, for whom he was named. We read his life, compiled by his spiritual children; we joyfully listen to the testimonies of his blessed life from our oldest nuns. Unfortunately, the majority of them have already reposed in the Lord, but there are still some witnesses to his podvigs both in the monastery and in the world.

We thank the Lord that he was given to the monastery in such a difficult time of persecution, war, and the tumultuous post-war years. Before his repose on March 29, 1960, he foretold that the monastery would soon be closed, which happened exactly a year later, in 1961.

He always helps when we turn to him to help our monastery, which is truly struggling to survive in the current conditions. And always, when something heavy, unsolvable comes, like a shadow, to our monastery, I turn to Ivan Petrovich, entreat his intercessions, and he always—always helps!

“He lived, for Thou didst create him. He died, for Thou didst call him,” reads the Elder’s gravestone

“He lived, for Thou didst create him. He died, for Thou didst call him,” reads the Elder’s gravestone

I’ll tell you about one of the miracles worked by Ivan Petrovich during his lifetime. A woman, a parishioner of another church, came here to the monastery. She told us what she had witnessed. She had come to our monastery in the 1950s as a child with her mother. She saw an old man who was half-naked and barefoot, walking on the snow and ice. The girl thought the old man must be very cold, and he was walking barefoot through the snow in such frost. “And when I thought this,” the girl said, continuing her story, “this old man suddenly came up to me, took me by the hand, and stood in front of me with his bare feet in a snowdrift. I remember his feet, so red and swollen. Then suddenly I saw steam coming from his feet into the snow. He leaned towards me, tenderly looked into my eyes, and said, “Grandpa isn’t cold!” Thus he saw the thoughts of a girl who remembered him her whole life, and then, as an adult, prayed for him and to him…

The Elder instructed us to pray for the repose of his parents Peter and Maria. People come to him at his grave, as to one living, with their sorrows and with joy, with requests and with gratitude.

To this day, the pious faithful continue the blessed work of feeding the hungry, begun by him during his lifetime.