When speaking about the Autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church 800 years ago, one always has in mind that the history of events related to St. Sava is quite well known to the general public, but what has particularly caught my attention at this time is the question: how the autocephaly of the Serbian church and the events around it can be a paradigm of the canonical acquisition of the autocephaly?

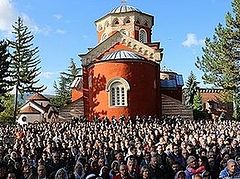

It is difficult to find an appropriate way to express the enthusiasm and gratitude for the great privilege of living in a time when our Church celebrates 800 years of its existence. It is a unique event not only for our lifetime, but for the history of our Church. Today, we are not only talking about history, but we are living, and perhaps even creating history. Not least today we should see ourselves as a link in the chain of many generations who left us the heritage to preserve, improve and pass on to future generations. Our hopes are that we are not a weak link, but it is certainly hard enough to keep up with the great figures and important events of the rich history of our Church.

When speaking about the autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church 800 years ago, one always has in mind that the history of events related to St. Sava is quite well known to the general public, but this time, what has particularly caught my attention is the question of how the autocephaly of the Serbian church and the surrounding events can be a paradigm of the canonicity of the acquisition of autocephaly? While I will be touching upon the theme of the autocephaly as a general term, I will not dwell on any particular, or rather, any other autocephaly in the history of the Church, except for that of the Serbian Orthodox Church. It would certainly be pretentious to even attempt an explanation of the philosophy behind the dynamics of the development of church history, in a relatively short article, let alone cover every segment of such a broad and complex, yet contemporary, interesting, and above all, significant topic.

According to the scriptural, hence also dogmatic understanding, the Church is one, since the head of the Church is one – the Lord Jesus Christ (Col. 1:18, Eph. 5:23, Hebr. 13:20 etc.). Although one, the Church was meant to encompass the whole world (Mt. 28:19). Since its outset, better known as the apostolic times, and during the first centuries of Christian history, the Church was developing from special centers, thus creating several local churches with national (local, distinct) characteristics, each with their own administration, yet united in faith. One of the characteristics of the Orthodox Church is that it has always retained the qualities of decentralization even after the multiplication of local churches (1 Cor. 12:12-14), a scriptural model that has been sealed with the canons.[1] This decentralized scriptural concept did not impact the true unity of the Church in any way. Therefore, from the outset, the Church saw itself as one, although she was divided into several autocephalous churches.

There are positive (via positiva) and negative (via negativa) expressions of the unity of the Church. Negative expressions are that autocephalous churches are divided, although only for administrative and practical reasons. In worldly terms, it could be said that the Orthodox Church is a single federation or free union of local churches, one body with distinct multiple administrative units, with the aim of avoiding a concentration of power and authority by any one individual or local church. At the same time there are positive expressions of the unity of the Church, where the unity is seen in the unity of faith, the actual unity of the presbyters (bishops, leaders) and laity (Jn. 17:21), consequently in the unified manner of canonical governance of all local churches. However, this unity of the Church can be preserved only if the established order by general Church legislation, adopted in the teaching of the Orthodox Catholic Church, and sealed by the life of the Church itself, is preserved. It is crucial to accentuate that it is only under the condition of unity that the Universal Church acknowledges the independence of the regional churches, who undertake an oath to preserve unity under canon law - the universal church rules and regulations. In an attempt for autocephaly, the Church must, first and foremost, be convinced that an initiative for unity is genuine and for the benefit of the universal Church. Having said that, it is important to note that the local churches are only conditionally independent. They are independent:

- in the election of their entire hierarchy and the head of their church[2]

- in the hierarchical rights and privileges of one church before others[3]

- independent in the administration and adoption of local legislation and independent court[4]

- they are independent in nurturing the ecclesiastical customs and rituals, which are not in opposition to the Orthodox Christian belief in any way.[5]

However, all local churches are dependent on the dogmatic teaching of the Orthodox Catholic Church, and therefore, according to the canons, they cannot and must not: a) introduce a new teaching on faith,[6] b) deviate from the laws and canons of the Universal-Ecumenical Church,[7] c) introduce novelties in faith to the Church,[8] d) demolish the unity of the Church by trampling upon the established order,[9] and e) offend the local rights and acquired customs of other churches.[10]

From these rather brief remarks, we see from the outset that the Church had clearly defined instructions, rules and regulations aimed at preserving unity in teaching, faith and spirit.

The formation of autocephalous churches was never accidental. Rather, it was a natural progression based on the practical needs of the Church. At the same time, the question of granting an autocephaly was of universal significance, thus from the earliest times until present day, the entire Church was involved. In the first centuries it was done through the Ecumenical Councils (autocephalies restored: Church of Cyprus, Church of Jerusalem). From the time of the Ecumenical Councils to present day, the assessment of the acquired rights of a church, remained under the jurisdiction of the bishops of the autocephalous church to which it sovereignly belonged at the moment of seeking autocephaly. Thus, the will of the Assembly of the autocephalous church in whose jurisdiction a part of the church seeks independence, i.e. the consent of the mother church, is one significant prerequisite for autocephaly. Only the Assembly of the mother church can give the consent to one part of its church to separate and become, in some cases, first autonomous, then autocephalous, and that can only be done by a church possessing full autocephaly for two reasons: 1) Autocephaly means sovereign authority over its territory, and consequently over that part of the church seeking independence, and 2) no one can give others what they themselves do not have. Without the consent of the mother church, there is no autocephaly. Otherwise, if other, external factors could do it on another church’s territory, then that local church would neither be sovereign nor autocephalous. Violations of these rules, established by the Orthodox Catholic Church since ancient times, inevitably always lead to schisms, since they are seen as anomalies and acts of arbitrariness.

With all this in mind, the question of the autocephaly of the Serbian Church arises. What does it mean to say that St. Sava gained the autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church? Could St. Sava have gained the autocephaly, or was he actually granted the autocephaly? In trying to provide an answer to these questions, we must first take a close look at the question of who was the mother church in the early 13th century to that part of the Orthodox Church in what was then Serbia? Was it the Archdiocese of Ohrid, or the Patriarchate of Constantinople?

We will briefly take a step back into history to gain an idea of the evolution and context of the period in question. It is apostle Titus (a disciple of the apostle Paul) who is considered to be the founder of Christianity in present-day Serbian lands[11], as he came across the coast, preaching the Gospel in that region (2 Tim. 4:10). For a short time, from 535 to 545, these regions were under the jurisdiction of the Iustiniana Prima.[12] The Christianization of Serbian tribes began during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (610 to 640)[13]. From the 8th century, the influence of Byzantium on Serbian lands was increasing, and through it the influence of the East, i.e. the Patriarchate of Constantinople. For a long time Serbs were divided between two centers, and to some extent between two jurisdictions.[14] From 927 to 971, much of the Serbian church fell under the authority of the Bulgarian Independent Church, and from 976 to 1018, most Serbian lands and the church were part of Samuel’s State and the Patriarchate of Ohrid. After the destruction of Samuel’s Empire and the Patriarchate in 1018, Emperor Basil II established a new church organization[15] in Ohrid in 1019, at the level of an archdiocese, covering almost the entire Balkan Peninsula.

As Serbian lands were part of the Archdiocese of Ohrid, the question arose: could she have given autocephaly to the Serbian Orthodox Church? This was immediately answered in the negative. The short answer is that the Archdiocese of Ohrid could not grant independence to the Serbian Church, because autocephaly can only be granted to one part of its territory by a completely independent, autocephalous mother church, and the Archdiocese of Ohrid had never canonically obtained complete autocephaly. Namely, the Archdiocese of Ohrid was created by an imperial decision, and imperial decisions in ecclesiastical matters were only relevant when they received consent from the Church. Thus, after the death of Emperor Basil II, all acts and privileges he gave to the Archdiocese of Ohrid lost significance, because the dioceses numbered in the imperial documents belonged, at least formally, to the Patriarchate of Constantinople. It is true that some Archbishops of Ohrid had attempted to impute themselves rights, which no one else had acknowledged. At last, they even tried to portray the throne of Ohrid as an extension of Iustiniana Prima, but since historically it did not stand,[16] these theses have never been acknowledged or endorsed by any church, especially the church of the Imperial City.

In short, the Archdiocese of Ohrid never had full autocephaly because the Archbishops of Ohrid were not elected by the Byzantine synod for the Church of Ohrid, rather, they were appointed by Byzantine emperors and ordained by the Patriarchs of Constantinople, at least until the second half of the 12th century, and the Church of Constantinople, as the mother church, never gave its consent for autocephaly to the Archdiocese of Ohrid. That is one reason.

Because of the broad subject, I will only mention and not dwell on the relative and secondary conditions for autocephaly, such as the independence of the state, the unanimous will among both the clergy and the people, and the ability of one part of the church to obtain autocephaly. All of these conditions were met by the Serbian Church, and it was never questioned. However, these relative and secondary conditions were not enough for an autocephaly.

At this point, I would like to say a few words about legal (canonical) factors that create autocephaly. Why is the autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church considered to be a canonical autocephaly? The autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church was considered canonical simply because St. Sava turned to the appropriate authority for the blessings necessary for his consecration as Archbishop and later for the autocephaly itself. Namely, St. Sava was a monk (an archimandrite) on Mount Athos. Mount Athos was under the direct jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople, thus all the monks and clergy were under the jurisdiction and spiritual authority of the Patriarch of Constantinople. Previously, we stated that even the Archdiocese of Ohrid was never granted full independence by its mother church of Constantinople, therefore, had St. Sava turned to the Archdiocese of Ohrid for autocephaly, he would not have been able to obtain it because Ohrid did not have the authority to grant it.

St. Sava However, when speaking about the canonicity of the autocephaly, the fact that St. Sava was a monk in canonical order, later an archimandrite (priest-monk) in canonical order always in good standing with the canonical church, is of absolute importance. And canonicity begins there; candidates for any church order, and certainly for the rank of a priest, a bishop and the highest orders, must be in canonical order with the Church. St. Sava was a canonical archimandrite, from which rank he was canonically consecrated as an Archbishop. At no point has anyone ever disputed his canonical status and rank while on Mount Athos. Thus, it would be against the canons of the Orthodox Catholic Church, and even highly problematic if St. Sava, as a cleric of Mount Athos, had turned to anyone other than his competent bishop, in this case, the Patriarch of Constantinople.

St. Sava However, when speaking about the canonicity of the autocephaly, the fact that St. Sava was a monk in canonical order, later an archimandrite (priest-monk) in canonical order always in good standing with the canonical church, is of absolute importance. And canonicity begins there; candidates for any church order, and certainly for the rank of a priest, a bishop and the highest orders, must be in canonical order with the Church. St. Sava was a canonical archimandrite, from which rank he was canonically consecrated as an Archbishop. At no point has anyone ever disputed his canonical status and rank while on Mount Athos. Thus, it would be against the canons of the Orthodox Catholic Church, and even highly problematic if St. Sava, as a cleric of Mount Athos, had turned to anyone other than his competent bishop, in this case, the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Here we may mention that St. Sava’s biographers recorded that, when talking to the Patriarch of Constantinople and Emperor about the need of the Serbian Church, St. Sava was not the only candidate, and he himself proposed one of the “brothers” from his entourage to be consecrated as the Archbishop, but the choice fell on him. It was only at the urging of the Emperor and Patriarch that St. Sava agreed. Of course, all this was passed by the Patriarch through the Council of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. So, when it was over, the consecration of St. Sava followed on a great feast day. The consecration of St. Sava was in the spirit of canonical regulations (Ap. 1; I Ec. Counc. 4; VII Ec. Counc. 3; Antioch 19 & 20; Laodicea 12; etc.), as well as the established practices in the Orthodox Church. Soon after the consecration for Archbishop, St. Sava received the decision of the Autocephaly from the Patriarch and Emperor, signed by the Patriarch, and all the Archbishops and Metropolitans, each by his own hand. The decision emphasized that in the future: the Archbishop (a Serb) himself (should make decisions) with the assembly of his bishops...[17] or that the bishops themselves should gather and consecrate their own Archbishops.[18] Thus, the election of St. Sava was both canonical and granted, rather than gained.

It is interesting that both biographers link the name of Patriarch Germanus II instead of Patriarch Manuel I with the consecration document for the Archbishop of the Serbian church. There are a few varying explanations of how this transpired. I, personally, would agree with Blagota Gardašević’s explanation in his article Canonicity of acquiring the autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the year 1219, who explains this in the following way: perhaps the attention of Domentian was drawn to a later document signed by Patriarch Germanus II. Attention should also be paid here to the awareness of local churches that the creation of an autocephaly is not only a matter of the mother church and the area that is separated, but of the whole Orthodox Church, because within the autocephalous churches there is a certain hierarchical church-legal order that cannot be changed by the will of individual churches alone.

There is a preserved document, issued a mere decade after St. Sava received autocephaly, regarding the renewed Bulgarian Church, which testifies to the procedure for acquiring autocephaly. Namely, upon receiving a request from Bulgaria, in this case again the competent Patriarch of Constantinople, Germanus II also addressed all Eastern Patriarchs: Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem for their consent and official agreement. It was only when the Patriarch received their consent that he, together with the assembly, signed and sent a document to the Bulgarian Patriarch in 1235, by which the Bulgarian Patriarchate was established, as well as sister relations among the churches. Therefore, it is possible to assume that St. Sava received the written consent of Patriarch Manuel I in principle, and only after obtaining the consent of other Orthodox Patriarchates, a document was sent to Serbia, with the signature of Patriarch Germanus II, who became Patriarch of Constantinople in 1222. That document was then read in all churches throughout the Archdiocese, which is how the biographers heard the name of Patriarch Germanus II.

A similar thing occurred, in more recent history of the Serbian Orthodox Church, upon the unification of the Serbian Orthodox Church and the reestablishment of the Patriarchate in 1920, by the decision of the Synod of the Patriarchate of Constantinople no. 2056 of March 19, 1920. However, an official document regarding this was signed by the new Patriarch of Constantinople, Meletius IV, with members of the Synod, only in 1922, which was read at a solemn worship service at the Cathedral in Belgrade the same year. Other autocephalous Orthodox churches were also consulted regarding this, and they too had sent their consent and recognition. Certainly, this small ambiguity about the name of the Patriarch of Constantinople, who signed the document upon the consecration of St. Sava, does not in any way diminish the canonical correctness of the establishment of the autocephalous Serbian Church in 1219.

Finally, I would like to briefly review the only known letter of protest from Demetrius Homatian, the Archbishop of Ohrid at the time, addressed to St. Sava after his consecration as Archbishop. As already stated, the Archdiocese of Ohrid held jurisdiction in the western part of the Byzantine Empire, in the despotate of Epirus, where Theodore Komnenos Doukas ruled from 1215 to 1230 as Emperor. Thus, the ruler of Epirus had ambitions to fully take over the Byzantine Empire. With such ambitions, Emperor Theodore Komnenos Doukas brought Demetrius Homatian, the most learned canonist of the time, to be the Archbishop of Ohrid. Therefore, it is doubly astonishing that he as Archbishop of Ohrid, is first, sending his protest letter to St. Sava, who is not the authority in question, and second, he avoids writing directly to the Patriarch of Constantinople, who is the actual competent authority. Be it as it were, while this protest comes from a famous canonist and orator, despite all the eloquence and emphatic sarcasm, it cannot be characterized as convincing at all. Initially, the Homatian strikes at the honour of St. Sava, and attacks his personal life, saying: Sava is leaving the monastic silence and returning to this tumultuous world, thus becoming a statesman, participating in state feasts, riding beautiful horses of the noblest breed and indulging in ceremonial processions with various escorts. But all this has nothing to do with his consecration as Archbishop and the establishment of the autocephalous Serbian Church. By citing specific canons he proceeds by making an attempt to thwart that which had already been granted to St. Sava, nor does he hide that St. Sava could have received an episcopal act of the consecration from him as well, only if he had addressed the lawful authority, according to him, "the head of the Bulgarian diocese." All of this indicated a mere personal ambition, not a canonical approach to the matter, since St. Sava was a clergyman of Mount Athos, which had always been, and still is today, under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople. Thus, Homatian’s letter to St. Sava was, unnecessary, to say the least, and what is particularly significant, is that all of the canons cited by Homatian in his letter to St. Sava, do not speak about the violations of the one who is consecrated as Archbishop, but of the one who performed the consecration. So, according to the canons he cited in his letter against St. Sava, Homatian would have done better had he actually sent his letter of protest to the Patriarch of Constantinople. However, he does not send his letter to the Patriarch of Constantinople, because he knows that he is not entitled to do that, and by sending the letter to St. Sava, a young and newly consecrated Bishop, he appears to have, as a goal, the intent to intimidate him, so that he might give up. However, he underestimated St. Sava's personality, ability and undeniable knowledge. Homatian’s apparent selfish and dishonest intent with the letter to St. Sava is fully manifested in 1222, after three years of independence of the Serbian Church, when he wrote a very kind letter to the new Patriarch of Constantinople, in which he showered with praise and exultation the throne of Constantinople. Nonetheless, if he felt the canonical right to do so, it was the perfect opportunity to, at least, mention his dissatisfaction with the consecration of St. Sava to the Patriarch of Constantinople, and yet, he did not mention a word.

It is also strange that in his letter to St. Sava, Homatian cites the canon which condemns the use of “nobility” and “imperial decrees” to establish ecclesiastical authority in a particular area, since it is well known that Homatian, personally, and the Archdiocese of Ohrid based their rights solely on imperial charters. In fact, at the same time, St. Sava based his rights on having the consent of the Emperor and the charter of the church authority.

It is also true that the Patriarch of Constantinople, Germanus II, later wrote a letter of protest to Homatian for holding on to his ambitions to crown the Byzantine Emperor. In his response Homatian unconvincingly tried to justify himself, attempting to link the Archdiocese of Ohrid with the privileges granted by the Pope of Rome to Iustiniana Prima, and so, according to him, the Archdiocese of Ohrid not only had the same rights as Constantinople, but also the same rights as the Pope of Rome. This was certainly a reflection of purely individual, arbitrary and ambitious interpretations. However, it helps us put things in the right perspective and they are mentioned for the sole purpose of making it clear that even in his response at such an occasion, Homatian did not protest, to the Patriarch of Constantinople, against the consecration of St. Sava. Knowing the unfoundedness of Homatian's protest to him, St. Sava also did not pay much attention to him. According to all available sources and data, even Homatian did not insist on his protest and he never took any further action against St. Sava

From all of the above, we can safely conclude that St. Sava obtained the autocephaly of the Serbian Church appropriately, on a completely canonical basis, in accordance with the ancient customs. Biographers of St. Sava, Domentian and Teodosije, clearly and unequivocally confirm that the autocephaly of the Serbian Church arose after the approval of the Byzantine Emperor, and that the main factor in the substantiation of this act was the consent and decision of the competent Patriarch with his Assembly of Bishops, which was in accordance with the ancient customs. St. Sava was chosen for the consecration to the rank of Archbishop while he was in good standing with the Church and finally, no Patriarchate has questioned the canonicity of the autocephaly of the Serbian Church. These three major factors are key to the proper understanding of canonical context of the Orthodox Catholic Church's autocephaly in any historical analysis, without exception.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Теодосије, Житије Светога Саве, Београд 1984; (Teodosije – The Life of St. Sava, Belgrade 1984)

- Доментијан, Животи Светога Саве и Светога Симеона, Београд 1938; (Domentian, Lives of St. Sava and St. Simeon, Belgrade 1938)

- Благота Гардашевић, Каноничност стицања аутокефалности Српске цркве 1219. године, у: Избор црквено-правних радова, Београд 2002.; Blagota Gardašević

- Ђоко Слијепчевић, Историја српске православне цркве, Минхен 1962; (Đoko Slijepčević, History of the Serbian Orthodox Church, Munich 1962)

- Јустин Поповић, Живот Светога Саве и Светога Симеона, 1962; (Justin Popović, Lives of St. Sava and St. Simeon, 1962)

- Константин Јиричек, Историја Срба, Београд 1988, (Konstantin Jiriček, History of the Serbs, Belgrade 1988)

- Станоје Станојевић, Свети Сава, Београд 1935; (Stanoje Stanojević, St. Sava, Belgrade 1935)

- Георгије Острогорски, Историја Византије, Сабрана дела књ. IV, Београд 1969; (Georgie Ostrogorski, History of the Byzantium, Belgrade 1969)

- Димитрије Богдановић, Измирење српске и византијске цркве, Православна мисао, Београд 1974; (Dimitrie Bogdanović, Reconciliation of the Serbian and Byzantine Churches, Belgrade 1969)

- V. Pospischil, Der Patriarch in der Serbisch-orthodoxen Kirche, Wien 1966

- Ко́рмчая книга, Москва 1787