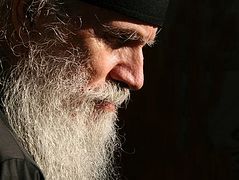

One of the greatest elders and workers of noetic prayer and teachers of both spiritual knowledge and of this prayer was Elder Barnabas the Elder, who came from Ayvali,1 and according to other sources, from Bogasia (Asia Minor),2 and who has already passed on to eternal life.

This blessed elder appeared in our last days like a sweet radiance that flared for a moment, illuminated these dark times, and then faded away and disappeared. This blessed father lived seventy years ago and was an abbot, and a truthful guide and mentor of active and contemplative virtue in the Skete of St. Basil.

In the Lausiac History, the Evergetinos, and the Patericon, we read about the times of the blessed abbas of Egypt, the Thebaid, Tabenna, and other places, and we admire the sojourn of these memorable fathers and the virtues that adorned their souls. We rejoice in the love and unanimity that prevailed among them, that respect and honor that they nourished for one another, and their voluntary poverty and complete renunciation of the necessities of life. The asceticism and competition of the monks between themselves in abstinence, silence, prayer, and vigil went so far that it is difficult for us to believe that in those times there could be found such a man who wouldn’t be jealous of this blessed and angelic life of the fathers of the desert and sketes of the Nitrian Mountain and other places. Looking at the victories, podvigs, and struggles of the monks of that time, set forth in various writings, we ask ourselves: Are there in these cruel times in which we live fathers who have succeeded in virtue, conducting their lives like these ancient monks and ascetics?

The blessed Elder Barnabas answers our question with his work, his virtuous life, and the example he has left us. As the memorable fathers cultivated the tree of virtues, which brought monasticism and the entire world examples of spiritual warfare, goodness, podvig, and a pure life, so too did this blessed Elder Barnabas become for his companions in the Skete of St. Basil the Great a model for imitation in spiritual struggles and the trials of the monastic life of those times by the bright example of his life, his love for everyone, and a whole chain of virtues.

If any of the current monks knew the virtue and spiritual life of the fathers of the Skete of St. Basil the Great on Athos, which Monk Barnabas, being already in advanced age, led as an abbot seventy years ago, they would see a genuine and unchanging example of the ascetic living of the monks of the Thebaid and Jordan, and would find a true copy of the ancient saints. It can even safely be said that in many respects, Elder Barnabas surpassed them. And we’re not exaggerating in the least, because he who has many allies in a fight can easily conquer; while he who fights alone, without any support or human help, who resists numerous and well-armed enemies, and he who manages to conquer them, is much more worthy of praise, honors, and crowns than he who has an entire army fighting on his side.

Thus, the fathers of ancient monasticism, the monk of the first centuries of Christianity rightly said that “the best of us is the monk who is tempted but unblemished in a place where there is no virtue.” The fathers said this because they foresaw that in the last times many temptations would arise. It’s not because the times are to blame, for the times don’t change—they always remain just as God created them—but because our faith has weakened, and our zeal for virtue and the pursuit of goodness is almost extinguished. And, as a consequence of this, indifference and laziness appear, from which are born doubt and unbelief.

Undoubtedly, we are amazed and even doubt, reading about the greatness of the spiritual life and the height of the virtues of these ancient ascetics in Sacred Scripture and in the works of the Fathers. As an example of abstinence, let us recall how pious pilgrims brought clusters of grapes to the Thebaid skete and left them at the door of the kyriakon (the central church of the skete), though none of the fathers partook of them, so the grapes were returned untouched to those who brought them. And St. Macarius, the presbyter of the skete, was not a little delighted with this abstinence contest between the fathers.3

When the elders would leave the spiritual assembly at Vespers or Divine Liturgy, the oldest of all, the abbot of the skete would put his finger to his mouth and say to the fathers: “Run, brothers, run!”

The monks would ask: “Where should we run to, Abba? And why should we run, Abba?” He would again put his finger to his lips and exclaim: “From this, let us flee, brothers!” showing them that it is necessary to avoid conversations among themselves, but for them all to go to their cells in silence, because, according to the Scriptures, in the multitude of words there wanteth not sin: but he that refraineth his lips is wise (Prov. 10:19).4

Let us now compare this with the spiritual state and virtuous life in the Skete of St. Basil, where seventy years ago this glorious Fr. Barnabas, after the example of the Thebaid fathers, decided, as the abbot of the skete, to introduce such a prayer rule. At the common gatherings on all the feasts and vigils, when all the monks gathered in the monastery kyriakon to pray together, Fr. Barnabas would exclaim: “Through the prayers of our holy fathers, Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on us!”

And at the word, “amen,” everyone would stand in his stasidia, in a cassock and kamilavka, prayer rope in hand, with the large light extinguished and the weak, dim flicker of the lampadas, so the church wasn’t too illuminated, and humbly, in a low voice, say the prayer, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me.” This went on all night, and at dawn, Fr. Barnabas would again cry out: “Though the prayers of our holy fathers…” and at the word, “amen,” everyone would leave the kyriakon, and Fr. Barnabas would lift his finger to his lips, saying nothing, and everyone understood that they should go to their cells in silence, to rest a little. Then, at the end of their cell rule, everyone would take up a handicraft.

In due time, Fr. Barnabas would go around to the ascetics’ kallyvias, watching after the brethren, making sure they were observing the typikon and rule immutably as it was handed to them by their fathers, and, having given spiritual advice and directions befitting to each, he would comfort, encourage, and strengthen the brethren so they could find success in spiritual battles. He especially cared for the brothers who, by their own will and with the blessing of the abbot, dedicated themselves to the practice of noetic prayer, examining them with all attention, so none would fall into satan’s nets, going down the path of delusion.

The ascetic rule of Fr. Barnabas was as follows: on weekdays, to eat xerophagy5 once a day, and on Saturdays, Sundays, and feasts of the Lord, and on days of the Most Holy Theotokos and those saints when the Horologion gives permission for wine and oil, to eat food twice a day, celebrating the Divine Liturgy on those days.

The fathers should have nothing superfluous and useless in their cells, only the most necessary things: a blanket on the bed, clothes, a bottle of vegetable oil and another with vinegar, a bag of rusks, and the necessary tableware. As Fr. Barnabas was very strict in observing this rule of asceticism, something happened one day that was as curious as it was serious. Going around to the brethren and going into one of the kallyvias, he saw three bottles and sternly asked the brother: “Brother, one bottle for oil, another for vinegar. And the third for what?”

The brother had nothing to say in his own defense and he remained unresponsive. Then Fr. Barnabas took the third bottle and broke it on the rocks. Thus, by this convicting act, Fr. Barnabas reminded the brother of the words spoken in the skete in the Egyptian Thebaid: “If you want soup, go to Alexandria.” In other word, he told him that “if you want bottles and casks and to have a good time, go somewhere else, to a cenobitic monastery, where there are storehouses, but don’t stay here to abolish the canon and typikon of the desert.”

News of this virtuous hermit spread all throughout holy Mount Athos, and brethren thronged to labor in obedience to him and under his guidance to walk the path of virtue and noetic prayer. And Fr. Barnabas subjected the brothers who desired to remain with him to a spiritual novitiate.

Here is one example:

The arrogance of a monk

When one monk from St. Paul’s Monastery arrived with the desire to become his disciple, Elder Barnabas asked him how the brothers of that monastery saw him. He answered the elder that all the fathers of St. Paul’s considered him virtuous, pious, and holy!

Elder Barnabas sighed deeply and said to the brother: “Brother, things are not good at all with you. You suffer a fierce demonic delusion and are secretly covered with arrogance and pride. If you want to correct yourself and deliver yourself of this delusion, listen to me carefully. How much did you eat and drink in your monastery?”

The monk answered him: “Father abbot, I was very abstemious in the monastery, and therefore the brothers considered me holy.”

Then Elder Barnabas said to Monk Nathanael: “You will go to your monastery and you will eat at the common meal, and you will eat the entire portion of food and drink all the wine apportioned to you—that’s your obedience, and when you finish eating and drinking, you will ask for a second and third portion.”

Monk Nathanael joyfully accepted this counsel and, having asked the blessing and prayers of Elder Barnabas, he headed for his St. Paul’s Monastery, and did everything he was told. But since he was not used to eating and drinking so much so quickly, he became so inebriated that as soon as he exited the trapeza into the clean air, he immediately passed out in front of all the brothers of the monastery.

Seeing his state and learning how much he ate and drank, the fathers thought he was possessed and were so sorrowful that they all began to lift up prayers to God that He would have mercy upon him. After that, the brother Nathanael, greatly ashamed, returned to Elder Barnabas and told him everything that happened at St. Paul’s. Then the wise and virtuous Elder Barnabas joyfully told Monk Nathanael: “Brother, now everything is alright with you.”

Thus healing him spiritually, he settled him in the skete’s last kallyvia.

Monk Nathanael thus settled there under the supervision, protection, and spiritual guidance of the elder, who, in order to occupy him with bodily podvig, appointed him to cultivate a small garden, where he planted onions, garlic, and other herbs. When the onion and garlic sprouted and Monk Nathanael began to rejoice because of it, Elder Barnabas came and started pulling them out and throwing them out of the garden. Pulling out the last plant, he asked Fr. Nathanael, who had grown them: “What do you think, brother? Are you saddened by the loss of the onion and garlic? Or did you grumble at me and condemn me for throwing them out? How do you feel, brother?”

Monk Nathanael answered the elder: “Venerable Father abbot, I was not saddened nor agitated, and did not condemn you, but I said to myself: ‘If the elder finds it proper, that means he undoubtedly did better than I would have done. God has enlightened you to do this, and may He be blessed!”

The reward for obedience

For his self-sacrifice, obedience to Elder Barnabas, and his behavior, Monk Nathanael reached such a height of virtue that he was noetically enraptured to Heaven many times. As a result of these states, God vouchsafed him the knowledge of His mysteries. During one of the vigils celebrated by the fathers of the kallyvia of the Entrance into the Temple of the Most Holy Theotokos, located below the kyriakon, as the Six Psalms were being read at Matins Fr. Nathanael was noetically enraptured and stood motionless in a stasidia until the ninth ode, when the fathers sang “More honorable than the Cherubim…”

At that moment, he awoke, crossed himself, and said: “Glory to Thee, O Lord, that Thou didst come to me!”

Such was the recompense for true obedience, which God crowns with graces and spiritual gifts.6