The Later Years of Father Andronik’s Mission

Fr. Andronkik (Elpindinskii) Following the failed attempt to start the mission in Colombo and the departure of Father Nafanail, Father Andronik was once again left on his own to continue the lonely task of preserving the Russian mission in India. The episcopal visitations had been the high watermark of activity in India during Father Andronik’s residence in the country and the decade following was one of quieter, much reduced activity in the Indian mission field, a situation undoubtedly exacerbated by the descent of much of the world into war.

Fr. Andronkik (Elpindinskii) Following the failed attempt to start the mission in Colombo and the departure of Father Nafanail, Father Andronik was once again left on his own to continue the lonely task of preserving the Russian mission in India. The episcopal visitations had been the high watermark of activity in India during Father Andronik’s residence in the country and the decade following was one of quieter, much reduced activity in the Indian mission field, a situation undoubtedly exacerbated by the descent of much of the world into war.

With the fall of France in the spring of 1940, Father Andronik was cut off from his bishop, Metropolitan Evlogii, and by extension the rest of the Church, having little to no communication with anyone else. Remote and isolated, he continued to make friends with the Indian Christians and work on the farm at his skete.

The war ended up bringing more Russians to India, with the largest groups gathering in Bombay and Calcutta. Once the war had reached the Soviet Union and many began to flee the country, he returned to the Kirichenko farm for the feast of the Nativity of Christ and had around sixty Russians attend, who all received confession and Holy Communion. Among this group were many readers and singers who assisted in the service. Most of them were transiting through India enroute to South America and Father Andronik reflected in his memoirs that it was just like serving in Russia, such was the number of people.[1]

The Anglican Bishop of Bombay also contacted Father Andronik and requested his help at an internment camp three hundred miles south of Bombay. Archbishop Sawa (Sovetov),[2] Orthodox chaplain to the Polish forces in Great Britain, had requested an Orthodox priest to visit the camp and minister to around one thousand Polish Orthodox Christians, many of whom were young women. Father Andronik served Divine Liturgy at the camp but, as he reports in his memoirs, there was considerable hostility towards him and the Russian Orthodox Church on the part of the Catholic Poles and many of the Orthodox were afraid to attend the services. Rocks were thrown at the chapel during services and even at Father Andronik as he came and went from the camp.[3]

The focus of Father Andronik’s work was now ministering to the Russian refugees who were arriving in India during the course of the war. The Russian Orthodox community in Calcutta had around eighty people, with a decent choir, and Father Andronik used the Armenian cemetery chapel for services, something that he had been doing on a non-regular basis since the 1930s.[4] When he was not present, he encouraged the Russians to attend Divine Liturgy at the long-established Greek parish. In Bombay, the community was smaller but better organised and Father Andronik was also able to secure the use of the Armenian church[5] for his services. Father Andronik served these two communities, as well as one in Delhi, for the remainder of the war.[6]

In 1947, noticing the need for Russian language instructors, Father Andronik decided to take up teaching, his former profession, at the Russian Department in the University of Delhi, hoping to be a point of contact for questions on Russian culture and religion.[7] He was to be disappointed, as there was little interest in this regard and the number of students shrunk to around thirty due to riots taking place in the city. Father Andronik was present in the city for India’s independence and the almost immediate establishment of the Soviet embassy there. Father Andronik was an eyewitness to the civil strife and internecine violence that continued for the rest of the year and carried on into 1948, coming close to being shot on several occasions. After less than a year at the university, Father Andronik quit his position and went to live on the farm of a Russian man in the Blue Mountains, where he worked on the land and unsuccessfully tried to establish a Russian spiritual centre.[8]

The Blue Mountains. Photo: moneyness.info

The Blue Mountains. Photo: moneyness.info

It is around this time, in June 1948, that reports began appearing in the religious press that the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church was on the verge of joining with the Moscow Patriarchate.[9] According to the reports, as he does not mention this correspondence in his memoirs, Father Andronik, hearing that religious freedom had been granted in the Soviet Union, sent letters to the Synod in Moscow encouraging them to actualise his hopes for union. With the Cold War beginning and India having just received independence, the ‘Great Game’ reared its head again and the British became very guarded. Father Andronik received word from the Saint Sergius Theological Institute in Paris that religious freedom in the Soviet Union was a myth and was encouraged to break off contact, which he did. Although the Indian church denied the rumours, it made the situation for the Indian Christians very tense for a short period, as suspicions about Soviet penetration were widespread.

In August 1948, he received a message from Bishop Ioann (Shahovskii),[10] possibly the same correspondence that told him to back off from the Moscow Patriarchate, telling him that the time was right to move on and recommending that he go to the United States. Father Andronik accepted his recommendations and began to prepare for his departure. He visited Travancore one last time to say farewell to his friends, handed his skete over to the local Indian bishop, and began preparing his documents.[11] He received a blessing from Metropolitan Vladimir (Tikhonitskii)[12] to serve in the United States and spent several months in Madras awaiting his visa. During this time, he made several pilgrimages to the place of Saint Thomas the Apostle’s martyrdom and was able to arrange with the local Armenian priest to serve Divine Liturgy in his church for the Russian community in Madras.

In May 1949, he boarded the cargo ship Dzhalakirti and took the slow route to New York, arriving in America in July. Father Andronik eventually served in both the United States and Canada and taught at Saint Tikhon’s Seminary in South Canaan, Pennsylvania, later becoming abbot of Saint Tikhon’s Monastery. He reposed in 1958, but his dreams for eventual union with the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church did not die with him.

Father Lazarus Takes Over the Indian Mission

Following the departure of Father Andronik, the missionary work of ROCOR in India ceased for a short period until one of his former partners in his missionary labours received an obedience to return to the subcontinent and revive the mission.

With the Synod of ROCOR having settled in Mahopac, New York in 1950, in the aftermath of the Second World War, it took a number of years for them to pick up where they had left off in terms of external missions. The situation was by now very different: a whole new wave of Russian émigré communities had spread across Europe, North and South America, and Australia after the fall of the former bastions of the Russian diaspora, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and China to communism.

Nonetheless, despite this situation of relative chaos and great suffering within the Russian diaspora, the Synod was still willing to respond to the appeals of those seeking to be united to the Orthodox Church. Archimandrite Lazarus (Moore), formerly Reverend Edgar Moore of the Church of England and temporary guest of Father Andronik at his skete, wrote a heartfelt letter[13] to the Synod about the desires of the Indian Christians to be united to Holy Orthodoxy on 31st March 1952. He explained that he had been given a substantial donation towards this endeavour by an anonymous benefactor, which could support the mission for some years, and that the current situation in Kerala, in which the catholicos and patriarchal parties were involved in constant litigation over ownership of church buildings and other properties,[14] called for immediate action. Thus, on 11th April 1952, the Synod restored the mission to India as The Russian Orthodox Malabar Ecclesiastical Mission, under the auspices of Father Lazarus.[15]

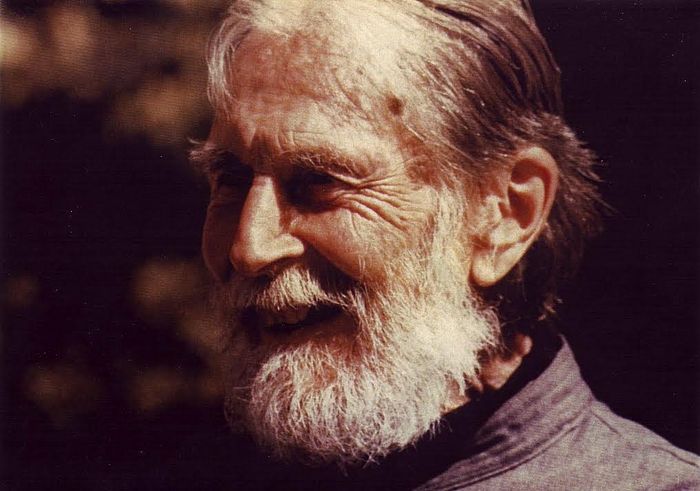

Fr. Lazarus Moore. Photo: rocorstudies.org

Fr. Lazarus Moore. Photo: rocorstudies.org

Edgar Harman Moore was born in 1902 in Swindon, England. Upon completion of his education at Elstree and Aldenham schools, he studied at the University of Reading Agricultural College before spending five years in Canada from 1921 until 1926, where he worked at a variety of jobs, including farmer, lumberjack, and longshoreman. Upon returning to England, he attended Saint Augustine’s College, an Anglican foundation established for the specific purpose of training clergymen to serve the Church of England across Britain’s far-flung empire. Upon completion of his studies, he was ordained deacon and priest in 1930 and 1931 respectively, serving at All Saint’s parish in Islington, London.[16]

In 1933, after two years of parish ministry, Father Edgar felt the call to serve in India and was despatched to Poone, where he joined the recently-formed Christian ashram Christa Seva Sangh,[17] which had been founded by Reverend John Copley Winslow[18] under the auspices of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.[19] Father Edgar began his ascetic life at the ashram and became involved with missionary work among the Indian Christians of Kerala, which brought his attention to the world of Eastern Christianity and, eventually, Orthodoxy.[20] In 1934, he left the ashram and joined Father Andronik at his skete for nine months, which is detailed above.

Following his departure from India, Father Edgar went directly to the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem and, from there, to the ROCOR Synod in Yugoslavia and then to Saint Panteleimon Monastery on Mount Athos, where he spent seven weeks. In late 1935, he was received into the Orthodox Church and subsequently tonsured into monasticism with the name Lazarus and ordained hierodeacon and hieromonk by Archbishop Feofan[21] at Milkovo Monastery, before being sent back to Jerusalem to serve in the Ecclesiastical Mission. He was to remain at the Mission until 1948, when he was forced to leave due to the Arab-Israeli War. He arrived in the United States in 1950, by then an archimandrite, to serve as the secretary to the Synod of Bishops at Mahopac in New York.[22]

Having received the blessing to depart for India by the Synod, Father Lazarus arrived in 1952, after a delay in London, along with Novice Joseph (Stewart), Nun Maria (Domverg), and Novice Maria (Pavlenko). At this time, Metropolitan Anastasii sent a covering letter[23] to the catholicos of the Indian church stating that he hoped to renew the discussions that had been abandoned due to the war and to complete the work of union that had begun in the 1930s with the visit of Bishop Dimitri. Father Lazarus had high hopes for the mission, he explained in a memorandum to the Synod, as the catholicos and the current generation of Metropolitans were “particularly pious” and a very dynamic group of individuals.[24]

In the winter of 1953, Father Lazarus engaged in extensive dialogues with Catholicos Baselios Geevarghese II, Metropolitan Alexios Mar Thevodasios, and Metropolitan Thoma Mar Divanyasios, regarding the Christological controversy of Chalcedon. The outcome of this was a statement by the Theological Commission of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church which produced a statement that was very favourable towards the Chalcedonian definition,[25] but nevertheless insisted on a union based on the first three ecumenical councils. Father Lazarus supported this move, although the Synod of ROCOR did not agree, telling him that common prayer and liturgy is only possible with the Indian church on the basis of their acceptance of the fullness of the Orthodox teaching, which specifically includes the seven ecumenical councils.[26]

By this time, Brother Joseph had left Father Lazarus and, having first taught at a school in Darjeeling, went to live at an Anglican monastery in Calcutta, although he was still loosely attached to Father Lazarus’ mission. Father Lazarus himself, having lived at the Indian monastery of Saint George for a time, was now living in the house of an Indian priest.[27] In addition to the work of the mission, Father Lazarus was also engaged in another work that would have profound significance for the world of English-speaking Orthodox Christianity: the translation of spiritual writings. During his time in India, Father Lazarus translated the Psalter, the Jordanville Prayer Book, An Offering to Contemporary Monasticism by Saint Ignatii Brianchaninov, and the Ladder of Divine Ascent by Saint John Climacus, as well as a number of short articles and sundry liturgical texts, services, and akathists.

In 1954, just before Great Lent, Father Lazarus attended another theological commission, this time including twelve Indian metropolitans and Russian theologian Dr. Nikolai Zernov,[28] who had been principal of the Catholicate College, a secular institution run by the Indian church, for over a year.[29] This commission had been formed at the initiative of Zernov while he was in India and it was his intention that Father Lazarus take over from him after his departure, but Father Lazarus’ subsequent moves from the area put an end to these aspirations.

With a stalemate having been reached in negotiations with the Indians, Father Lazarus made the first of several moves in India, relocating to the village of Kotagiri in the Nilgiri Hills region of the state of Tamil Nadu, just across the state border of Kerala. Almost immediately after arriving in the area, Father Lazarus befriended A.J. Appasamy,[30] an Anglican bishop from the Church of South India[31] who was active in the area. Bishop Appasamy recounts that Father Lazarus used to walk six miles to and from his place of residence in order to help him edit a book he was writing. Father Lazarus also translated prayers from the Orthodox service for the feast of Pentecost for churches in the Coimbatore diocese to use in both English and Tamil during the season of Pentecost. As a result of this cooperation, Father Lazarus made and maintained friendships with the local Anglican clergy and was often invited to preach in their churches on feast days, as well as to read learned papers at conferences and meetings.[32]

The missionary work enters something of a quiet point at this stage and, from the records that are available, it seems like Father Lazarus dedicated most of his time to ascetic labours and translation work. The quietness of the mission was undoubtedly noticed by the Synod, which wrote to Father Lazarus in July of 1960, intending to recall him to the United States. Father Lazarus was able to convince them to allow him to stay as he had not only commenced learning Tamil, the language of the predominately Hindu locals, but the missionary brotherhood was beginning to be rebuilt, with two men, Novice Joseph (Yavorskii) and George, now living with him and another, Albert, due to arrive.[33] Novice Joseph was a Ukrainian from Canada who had muscular dystrophy and was effectively a cripple, while George was an Indian and a member of the Church of South India who was interested in Orthodoxy. Nothing is known about Albert other than that he was Belgian.

Father Lazarus was later able to report that some Hindus from the local village were willing to become Christian, but that their village was too much of a distance away for it to be practical.[34] The following year, he wrote to Metropolitan Anastasii asking for a blessing to receive into the Orthodox Church another member of the Church of South India, Sevak V.C. George, who was leader of an Anglican ashram in Varkala, Travancore.[35] The man intended to live with the missionary community following his reception into the Church. It can be assumed that the blessing was given, but nothing more is heard about him in later correspondence from India. Likewise, there are no further reports from the period that mention further interest from the local Hindus.

The major highlight of the Kotagiri period of the mission is, from the perspective of the Synod in New York, Father Lazarus’ visit to New Delhi to take part as an observer in the General Assembly of the World Council of Churches in 1961. Father Lazarus received this obedience from Archpriest George Grabbe,[36] who intended for him to gather information on the activities of the Moscow Patriarchate’s delegation. Father Lazarus attended a number of sessions and wrote a report back to the Synod which was rather critical of both the Orthodox Church and the World Council of Churches. Within two years, Father Lazarus and the mission would be on the move again.

The Mission Moves to North India

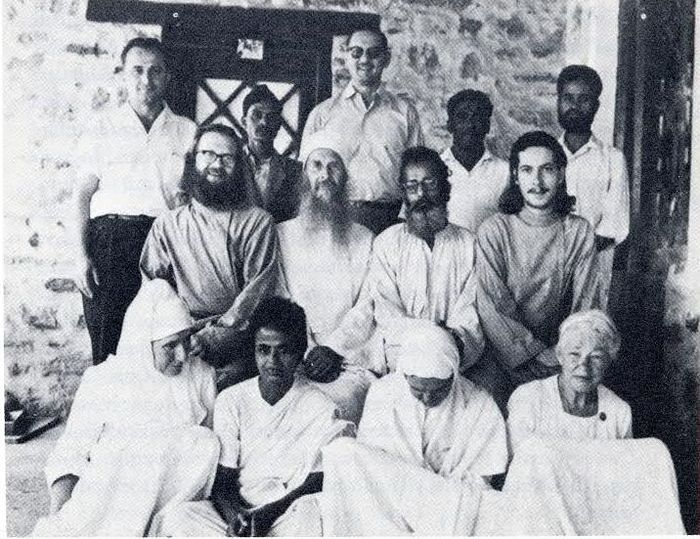

Fr. Lazarus with fut. Archim David Meyrick (center row, left) and Leon Liddament (center row, right). Gerontissa Gavrilla (front row, left). Ashram in Utta Pradesh. 1963. Photo: rocorstudies.org

Fr. Lazarus with fut. Archim David Meyrick (center row, left) and Leon Liddament (center row, right). Gerontissa Gavrilla (front row, left). Ashram in Utta Pradesh. 1963. Photo: rocorstudies.org

Frustrated with his lack of success in the negotiations with the Indian bishops and the lack of progress among the Hindus of Tamil Nadu, Father Lazarus eventually decided to leave the Kerala area and relocate to the north of India, an area where the Christian population is dramatically lower than the south and the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church has less of a presence. In 1963, he moved to the Sat Tal Ecumenical Ashram[37] in the state of Uttar Pradesh, where he formed a small Orthodox community initially consisting of Novice Mark (Meyrick),[38] Novice Leon (Liddament),[39] and Sisters Mary, Lilya,[40] and Thomais.[41] The ashram was owned by the Methodist Church in India, who later ordered everyone off the property, with the exception of Father Lazarus.

Sister Lilya, later to become well-known as Gerontissa Gavrilia, noted that there were a number of locals who had converted to Orthodoxy and formed a small parish around Father Lazarus, who became distinguished by his bright white riasa.[42] She writes that Father Lazarus celebrated the Divine Liturgy every day and that many of the local Hindus were enamoured by the rituals of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Regarding life in the Orthodox community at Sat Tal, the daily schedule included a wakeup call at five o’clock in the morning, followed by silent prayer, the reading of the Gospel, and various obediences. There was an hour’s study of the Holy Scriptures at noon, followed by discussion and then two hours of silence. In the evening, Vespers was celebrated, followed by a meal and conversation with visitors about spiritual topics.[43]

It can be assumed that, like Father Lazarus’ time in Kotagiri, that monastic labours and translation work took up the majority of Father Lazarus’ time at Sat Tal, as there is no available correspondence between him and the Synod to indicate that the mission work taking place in the area was very productive, although a young man named Alan was sent to Father Lazarus by Gerontissa Gavrilia. He was received into Orthodoxy with the name Hadrian and became a missionary, although it is not known where or for which jurisdiction. The exception to the lack of progress on the missionary front is the case of Father George Tharian, detailed below, which occupied central place in Father Lazarus’ activities between 1964 and 1969. He was also able to make a short missionary journey to Kenya, where he assisted for a time in the work of the Patriarchate of Alexandria.[44]

Ultimately, although he mentioned many times in his letters that he intended to patiently see his work through to the end, Father Lazarus departed for Greece in 1972 after the local police gave him two months to vacate the premises of the ashram or face imprisonment.[45] Upon receiving this news, Father Lazarus decided to embark on a water fast until he received a revelation about where to go next. After nineteen days, he received an invite to go to Greece to conduct Bible studies, thus ending twenty years of missionary labours in India on behalf of the Russian Orthodox Church. Father Lazarus was subsequently invited to Australia, before moving on to California, and finally, Alaska, where he reposed in 1992.

Father George Tharian and the Search for a Bishop for India

Father George Tharian Although negotiations with the prelates of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church had proved fruitless, an opportunity arose for ROCOR to unite at least a portion of the Indian Christians to the Orthodox Church in the form of the priest George Tharian and his followers in the reunion movement. Although Father Lazarus was involved with the process, it was Metropolitan Filaret and Father George Grabbe who played the key roles in trying to steer this movement into the arms of ROCOR.[46]

Father George Tharian Although negotiations with the prelates of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church had proved fruitless, an opportunity arose for ROCOR to unite at least a portion of the Indian Christians to the Orthodox Church in the form of the priest George Tharian and his followers in the reunion movement. Although Father Lazarus was involved with the process, it was Metropolitan Filaret and Father George Grabbe who played the key roles in trying to steer this movement into the arms of ROCOR.[46]

Beginning in 1964, a group of clergy and laity from the Jacobite Syriac Church of India, led by Chorepiscop[47] Dr. George Tharian of Thariannagar near Kochincherry, began to correspond with Father Lazarus as they sought to enter the Orthodox Church. This movement had embraced the full faith of the Orthodox Church, including the council of Chalcedon, and had even purified their liturgical texts of references to monophysite saints such as Severos and Dioscoros.

In his first letter to Father Lazarus, Father George Tharian explained that his group, which consisted of six priests and several hundred faithful, had been trying to contact the Greek Orthodox from 1961 onwards, with little success.[48] In fact, their petition to the Ecumenical Patriarchate had met with outright rejection from Patriarch Athenagoras,[49] who ordered Father George to “cease dividing the Orthodox Syriac Church in Malabar and put an end to the troubles and turmoil which you create in it!”[50] As the Indian church had long-term links with the Monophysite See of Antioch, the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch was their preferred option,[51] but, since Father Lazarus was first point of contact, he found himself in communication with ROCOR. The group’s title at this time was the ‘Greek Orthodox Church of India,’ although this was to change several times over the following years. Father George Tharian had been directed to Father Lazarus by Father George Theckedath,[52] an Indian priest who was allegedly planning to join the Orthodox Church and study at Saint Vladimir’s Seminary in the United States.[53]

Several months later, Father Lazarus reported back to Synod that the “reunion movement” now had around seventy-five priests and thousands of laity.[54] Their urgent request was for a metropolitan to be sent to help the church properly establish itself, which, according to Father George Tharian, would lead to many supporters of the catholicos party joining the endeavour.[55] It is evident from Father Lazarus’ letters that the Synod’s slow response to the situation was frustrating to him, but once Metropolitan Filaret responded, the situation began to move very quickly.

Metropolitan Filaret wrote directly to Father George Tharian, assuring him of his wish to assist to the best of his abilities. His main questions to the movement regarded their liturgical uses, their calendar, and fasting regulations. He recommended several books that included the canons of the seven ecumenical councils. Regarding the liturgy, as Metropolitan Anastasii had already decided that the Indians could maintain their own liturgical rites with whatever doctrinal modifications were necessary, Metropolitan Filaret requested, if possible, an English translation. He also expressed interest in translating the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom into Malayalam, so that it could be celebrated on certain days, in order to reinforce the unity of the churches.[56]

Father George Tharian’s prompt reply to the Synod contained a biography, from which we are able to glean the important details of his life. He was born in 1924[57] and studied art and medicine in Bombay before working as a medico.[58] He owned a large pharmaceutical plant in Bombay, which he sold in 1955, as well as a hospital and other businesses, and he produced several popular Christian films. Upon giving up the business life and activity in politics, he was ordained to the priesthood by Metropolitan Elias Mar Yulios[59] in 1960 and elevated to the rank of chorepiscop[60] in 1961, being appointed the Envoy Plenipotentiary of the Holy See of Antioch for the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.[61] Prior to ordination, he had been married with one son, a situation that later caused some problems for his movement.

On the strength of his biography and several other materials supplied to the Synod, he was officially invited to the Synodal headquarters by the Chancellor, Father George Grabbe,[62] where he was to spend a month as a guest. At this point, Father George Grabbe took the lead in communicating with his namesake in India, and was to show much concern, patience, and optimism over the next three years.

On 2nd January 1966, Father George Tharian was received into ROCOR as an archimandrite by confession of faith and vesting at the Synod Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign in New York.[63] Two days later, Metropolitan Filaret and Father George Grabbe signed a document announcing the reception of his movement into the Orthodox Church, instituted as the Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic Church of India,[64] with Archimandrite George as administrator and an episcopal see to be filled, pending the election of a metropolitan.[65] It is not clear from the available documentation how Archimandrite George was to receive the people of his movement into the Church. It is possible that the Synod used a degree of oikonomia, similar to the reception of Saint Alexis Toth and the Uniates into the Orthodox Church.[66]

With the mission now officially under the protection of the Synod, the search began for a bishop to shepherd the newly-received flock. Metropolitan Filaret’s first choice, and the obvious candidate, was Father Lazarus, but he strongly objected to the notion, due his self-perceived unworthiness of the episcopal rank, in a letter sent to the Synod.[67] Also considered for the see was the then-recently ordained priest, Father Dmitri Alexandrov,[68] who had a working knowledge of Syriac and was learning Malayalam.[69] With the news of Father Lazarus’s rejection, Father George Tharian reached out to Metropolitan Filaret to explain that he would be willing to become the Metropolitan of India, after discussions with the people in his movement. He stated that he was not fit or worthy, but would be willing if the Synod made such a decision.[70]

The news of Father George Tharian’s reception into the Church as an archimandrite and the search for a bishop was a cause for some concern to Father Lazarus. In a letter to the Synod, he raised the issue that Father George Tharian, who had been a married priest, was still living at the family home with his wife, who had not become a nun. Although the home consisted of two buildings, one for men and one for women, this was common practice in India and should be considered “living together.” He suggested that no one be consecrated bishop for India, but that the Synod should instead send an experienced bishop who could effectively catechise the people and receive them into the Church properly.[71] The confusion could possibly be attributed to the fact that a chorepiscop can be either married or monastic. It may well be that Father George Tharian, when he referred to himself as an archimandrite, did not know that it was a specifically monastic role.

Around the same time, Father George Tharian had been making contact with the Tolstoy Foundation,[72] in order to secure financial support for the mission, as well as asking Father George Grabbe for donations of literature, vestments, and other necessities. He promised that a monastery, seminary, orphanage, and twenty-five other institutions would be formed by August 1967 if the aid was available.[73] The monastery and orphanage were to be located on a newly-purchased coffee plantation at Wynad on the Malabar Coast and named Moran Mar Anasthassi Monastery and Orphanage (Greek Church).[74]

In the autumn of 1967, Father George Tharian was officially invited to the diocese of Geneva and Western Europe by Archbishop Antonii (Bartoshevich),[75] who gave his blessing for him to lecture in his parishes. This came after Father George Tharian returned from seven weeks in Greece and Lebanon, where he encountered Greek Old Calendarist bishops who wanted to consecrate him immediately.[76] Father George Tharian reported to Father George Grabbe that the Old Calendarists had left a very bad impression on him due to their factionalism and extremism and that he wanted nothing to do with them.[77] It was this letter to Father George Grabbe that renewed contact after more than a year of silence, which had left Father George Tharian concerned that he had been disowned by the Synod, a rumour that his enemies in India were spreading. He raised these concerns to Father George Grabbe, as well as asking about the status of Father Lazarus—was he under the new mission, or still directly under the Synod?[78] At the same time, Father George Tharian’s former wife, Mary George, wrote a letter to the Synod confirming that she had indeed separated from him at the time of his entry into monasticism and elevation to chorepiscop[79] and was intending on entering a convent as soon as one was established.[80] There are no available records in India to corroborate this, so the question of how and when Father George Tharian became a chorepiscop or archimandrite cannot yet be answered.

Fr. Geroge Grabbe shortly after World War II. Photo: rocorstudies.org Contained in the letter to Father George Grabbe was a copy of the resolutions of the third general convention of the reunion movement, now known as the Saint Thomas Eastern Orthodox Church of India, which occurred on 27th and 28th of August 1967.[81] The preamble stated that the group was “an independent, self-governing jurisdiction of the ancient Holy Orthodox Catholic Apostolic Church,”[82] although it was still without a bishop. No members of the council were named in the document, with the exception of the secretary, V.D. Arical. The resolutions included accepting the use of the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom as an occasional liturgy, as proposed by Metropolitan Filaret; petitioning the Synod to consecrate Father George Tharian as Metropolitan of India; petitioning the Synod to consecrate another metropolitan, who is not Indian, to remain in the United States for fundraising activities; petitioning the Synod to receive permission to enter in dialogue with the “National Church of India”[83] and the Chaldean Syrian Church.[84]

Fr. Geroge Grabbe shortly after World War II. Photo: rocorstudies.org Contained in the letter to Father George Grabbe was a copy of the resolutions of the third general convention of the reunion movement, now known as the Saint Thomas Eastern Orthodox Church of India, which occurred on 27th and 28th of August 1967.[81] The preamble stated that the group was “an independent, self-governing jurisdiction of the ancient Holy Orthodox Catholic Apostolic Church,”[82] although it was still without a bishop. No members of the council were named in the document, with the exception of the secretary, V.D. Arical. The resolutions included accepting the use of the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom as an occasional liturgy, as proposed by Metropolitan Filaret; petitioning the Synod to consecrate Father George Tharian as Metropolitan of India; petitioning the Synod to consecrate another metropolitan, who is not Indian, to remain in the United States for fundraising activities; petitioning the Synod to receive permission to enter in dialogue with the “National Church of India”[83] and the Chaldean Syrian Church.[84]

By the end of the year, Father George Grabbe had responded to Father George Tharian and confirmed that Metropolitan Filaret was happy to present him to the Synod as a candidate for episcopal consecration, provided that he deliver more substantial documentation to the Synod regarding the status of his wife.[85] Several months later, Father George Tharian received a decree from the Synod recognising his divorced status as valid,[86] thus removing the major barrier to his election as bishop. In September of that year, the Synod held a meeting to make a decision on the Indian mission and the vote was in Father George Tharian’s favour to be consecrated as bishop for India. An ukaz was issued stating that there were a total of eleven votes for, two against, and nine absentees.[87] The bishop-elect was to come to the Synod in New York at an unspecified date to spend two months in preliminary preparations before being consecrated.

It is interesting to note that, of the three bishops that had met Father George Tharian—Metropolitan Filaret, Archbishop Antonii, and Bishop Lavr (Skurla)[88]—one, Archbishop Antonii, voted against. The other vote against him came from Archbishop Antonii (Medvedev) of San Francisco,[89] who advised against such a move in the wake of Kovalevsky[90] and the ECOF[91] schism.

This vote went ahead despite the letter received from Father Lazarus in the summer, in which he stated his opposition to the consecration of Father George Tharian as a bishop. He wrote that, despite Father George Tharian being a good and friendly man, he did not deem him suitable for the episcopacy due to several factors, notably his lack of theological education, his lack of knowledge of the Holy Scriptures, and his lack of spiritual knowledge and ability to lead people in the spiritual life. He also mentioned that an unnamed Greek bishop had contacted him and asked whether or not it was wise to consecrate Father George Tharian as a bishop.[92]

Ultimately, Father Lazarus’ view won out, as, not long after Father George Tharian became bishop-elect for India, the plans were abruptly cancelled, although not as a direct result of Father Lazarus’s letter.

The Synod had received a copy of one of Father George Tharian’s books, Maitbuna Buthikal, which contained images and content deemed inappropriate for a clergyman and medical doctor. Father George Grabbe informed him that it was decided, since the book had been sent by someone hostile to him, that it would be in the best interests of the church to cancel his consecration, as it would make the church vulnerable to its enemies.[93] It is possible that there is more to this than simply what was stated in the letter to Father George Tharian and, while there is nothing to suggest this from the extant documents, it could be that the nature of his medical work—family planning and contraception—played a role in the Synod’s decision to cancel the consecration.

There is no more extant correspondence after this, so it seems like Father George Tharian ceased contact with ROCOR around this time. Nothing more is known of his activities after this point but it is known that Father George died in 1974, at the age of fifty, so the Saint Thomas Eastern Orthodox Church of India most likely died with him. What is known is that he never renounced the Orthodox faith, although he was given a Church of South India burial at the CSI parish of Punnakkadu, due to the absence of Orthodox clergy to bury him.[94] So, it appears that he lived and died his last few years as a clergyman of ROCOR, although he did not appear to maintain communication with the Synod.

Father George Tharian is an interesting case, as many of his activities are highly suggestive of the behaviour associated with vagantism: regular name changes for his movement, elaborate promises to open institutions such as seminaries and monasteries, uncorroborated stories of large numbers of followers, requests for money and supplies, requests for autonomy, and indirect requests to be consecrated bishop. At the same time, from his correspondence it is clear that he turned downed opportunities to be consecrated by Greek Old Calendarist bishops, never received consecration from anyone after his estrangement from ROCOR or even joined another Orthodox body, and was fairly modest in his financial requests, so the case for him being genuine in his wish to be united to the Orthodox Church is strong. Father Lazarus, who met him in person and spent time in South India with his community, was also very keen on receiving him into the Church and showed genuine optimism and enthusiasm for the movement.

Although Father George Tharian shares many traits with episcopi vagantes and was misleading in many of his statements to the Synod, the fact that he remained loyal to Orthodoxy and never sought consecration at the hands of an independent bishop after his rejection by the Synod is in his favour. The final judgement on Father George Tharian should come from his own diary: “Many know me but nobody knew me,”[95] an enigmatic statement if there ever was one.