Introduction by Matfey Shaheen:

This article concerns the heortology (the study of the religious holidays and festivals) of Christmas. This holiday is known to Orthodox Christians by the full name, the Nativity according to the Flesh of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

While that name seems quite long, there is actually a very important theological purpose for this name. Jesus Christ is of course, the Son of God, and therefore, God, and as a result, an important question regarding His Nativity arises, so important that it took an entire ecumenical council to resolve it. If Christ (God) was born of the Virgin Mary (ex Maria Virgine) then the Virgin Mary is the Mother of God; but does that mean that in the most technical sense, God was literally born (and did not exist prior to) the Nativity of Christ? Of course not, that is heresy, specifically the heresy of Nestorius, erstwhile Patriarch of Constantinople, who was condemned along with his teaching by the Third Ecumenical Council. Nestorius believed that the Theotokos could only be called the Mother of Man, or Mother of Christ (Christotokos), but not the Mother of God, as technically, she did not obviously give birth to the Holy Trinity or even to the Pre-incarnate Logos.

However, it is clear that Christ is God the Logos, who became incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and therefore, as she is the Mother of Christ, and Christ is both Man and God, then she is also the Mother of God, as to say otherwise would deny that Christ is fully God. The Divine and Eternal Logos did not simply incarnate, but became the God-Man Jesus Christ, and therefore, the Church acknowledges this mystery, that the Theotokos gave birth to not only her own Creator, but the Creater of all existence, by saying that her whom is more spacious than the heavens, for it contained in one moment the One who all the heavens can not contain.

Jesus Christ, the only Man with a pre-history, was born in the flesh of the Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary, and the whole world rejoiced.

While there are many services and joyful events, such as Christmas caroling, relating to the Nativity, this specific article concerns the complex history of the origin of the festal celebration itself, its traditions, liturgies, and history. Regarding the calendar, essentially all events described in this article take place before the invention of the new calendar, and as a result, all dates are given as if on the Old Calendar (December 25 in this article means January 7 on the secular calendar).

It is often misunderstood that the Old Calendar date of Christmas is January 7. In fact, both the Old Calendar and the New Calendar agree, that the date of Christmas is December 25; the difference is that December 25 according to the Old Calendar is actually January 7 on the New Calendar, which we use in the secular world. So, in fact, those on the Old Calendar still celebrate Christmas on December 25, however that date translates to the modern calendar day, which most of the world recognize as January 7.

That means, for example, that throughout the article, when January 6 is written here, this is referring to the day most people would call January 19. The Old Calendar date is thirteen days before the date on the New Calendar.

The wonderful events of the Nativity of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ

The Lord Jesus Christ, the Savior of the world, was born of the Most Holy Virgin Mary in the city of Bethlehem during the reign of Emperor Augustus. Augustus commanded that a census be conducted across the entire Roman Empire, which at that time included Palestine. Among the Jews there was a custom of conducting censuses by generations, tribes, and clans; every tribe and clan had their own particular cities and ancestral dwelling-places, therefore the Most Blessed Virgin and the righteous Joseph, as descended from the house of David, had to go to Bethlehem (the city of David) to add their names to the list of Caesar's subjects.

The Lord Jesus Christ, the Savior of the world, was born of the Most Holy Virgin Mary in the city of Bethlehem during the reign of Emperor Augustus. Augustus commanded that a census be conducted across the entire Roman Empire, which at that time included Palestine. Among the Jews there was a custom of conducting censuses by generations, tribes, and clans; every tribe and clan had their own particular cities and ancestral dwelling-places, therefore the Most Blessed Virgin and the righteous Joseph, as descended from the house of David, had to go to Bethlehem (the city of David) to add their names to the list of Caesar's subjects.

In Bethlehem, they could not find a single free place in the city to stay. And so it was, that in a limestone cave intended for a stall, amongst hay and straw scattered for feed, and litter for livestock, among strangers, in an environment devoid of not only earthly grandeur, but even ordinary convenience, the God-Man, the Savior of the world, was born.

The first to mention the birth of the Savior in the cave was St. Justin Martyr, who lived in the second century, and in the time of Origen, the cave in which the Savior was born was already known. After the end of the persecution of Christians, Emperor St. Constantine the Great built a church over this cave, concerning which the ancient church historian Eusebius wrote.

This cave, as many authors believe, was in a [small—Trans.] mountain, which began to be correlated with the Virgin Mary herself, and the cave—with her womb, the container of the Uncontainable God. According to another interpretation, the cave is understood as a dark place, meaning the fallen world in which Jesus Christ the Sun of Righteousness[1] shone forth.

Painlessly giving birth to the Divine Infant, the Most Holy Virgin herself, without needing help, wrapped Him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger (Lk. 2:7). But amidst the silence of midnight, when all of humanity was embraced by the deep sleep of sin, the news of the Nativity of the Savior was heard by shepherds who were keeping their flock in the night.

An angel of the Lord appeared before them and said: Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord (Lk. 2:10-11), and humble shepherds were the first to be vouchsafed to worship the One who deigned to acquire human flesh[2] for the salvation of man.

In addition to the angelic annunciation to the shepherds outside Bethlehem, the Nativity of Christ was proclaimed by a wonderful star to the magi-astrologers: according to the explanation of the Holy Fathers, the star, among other things, was an embodiment of angelic powers.[3] In the form of the Three Magi, the entire pagan world, unbeknownst to itself, knelt before the true Savior of the world, the God-Man. Entering the little temple where the Infant was, the magi fell down, and worshipped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense, and myrrh (Mt. 2: 11).

Issues of Heortological Syncretism: the holidays of the Nativity of Christ and the Baptism of the Lord

The question of establishing the feast of the Nativity of Christ is in close relation with the heortological[4] history of the Feast of the Baptism of Christ [often called Theophany].

Since the end of the sixth century, this problem has gained unprecedented urgency, being at the epicenter of disagreements between the defenders of the Orthodox faith and their opponents—representatives of the Armenian Church, who did not accept the Council of Chalcedon. Arguing with each other on the topics of rites, the Byzantines and Armenians gave them an almost a doctrinal value. For the former, it was taken for granted that Christmas and the Baptism should be celebrated on December 25 and January 6,[5] respectively. The latter, on the contrary, were convinced of the need to celebrate both of these holidays on the same day—January 6th. Both parties did not doubt the antiquity and apostolic origin of their liturgical tradition and did not intend to yield to each other.

Photo: A.Pospelov / Pravoslavie.ru

Photo: A.Pospelov / Pravoslavie.ru

The historical and liturgical origins of the feasts of Nativity/Theophany are revealed in connection with the internal reasons for establishing its date. It was calculated, firstly, by adding a certain number of days to the date of the Annunciation, which almost coincided with Easter, and, secondly, by identifying the day of the coming of Christ the Savior, the second Adam, to the day of the creation of the first Adam. Both correspondences were closely related to the characteristics of the ancient Jewish tradition, partly inherited by Christians.[6]

The ancient Jews paid not so much attention to the birth of a righteous person, as to his death, which became the starting point not only for the coming eternity, but also to determine the beginning of the life of a holy man. From this, the following circumstance becomes quite logical: the Paschal feast in the minds of the ancient Christians began to coincide with the time of the Incarnation, with the day of the Archangel’s Annunciation, in which, according to the testimony of the Holy Scriptures and the tradition of the Church, the saving Fruit appeared in the womb of the Blessed Virgin. The addition of nine months—the usual term of pregnancy—to the estimated time of the Incarnation and led to the determination of the date of the Nativity of Christ.

If we count back nine months, March 25 precedes December 25, and April 6—January 6. In the calculations of the ancient Christians, we encounter both dates. Thusly, Sozomen, in his Church History reports that the Montanist heretics in Asia Minor understood the day of the vernal equinox as a starting point for calculating Pascha—this is the celebration of the beginning of the world, the beginning of the creation of the sun and the first month.

Another date of the Lord’s Passion—March 25—is mentioned in a much larger number of sources, mainly Western. According to the arguments of Tertullian, St. Cyprian, and others, the days of the Passion of Christ and the Incarnation coincide.

Then the ancient Christians confined themselves in their calendar-liturgical cycle to the celebration of Pentecost and Pascha, which almost coincided in time with the Incarnation, and thus they naturally correlated the creation of the world and the old Adam with the time of the coming into the world of the new Adam—Christ. So, for example, in the work “On the calculation of Easter”, March 25 was identified as the day of the creation of the world, and the birthday, or Incarnation, of Christ, fell on the fourth day from the creation of the world, coinciding with the day of the creation of the sun.

According to a fairly widespread, although unproven point of view, the celebration of the Nativity of Christ on December 25 was established in the North African and Roman Churches up to 311—the year the Donatist schism began. This dating was based on the testimony of St. Augustine that the heretics did not recognize Theophany, or Epiphany[7] [literally in the Russian text—Revelation—Trans.] the adoration of the Magi to the newborn Savior—which is celebrated by the Church. It should be noted here that St. Clement of Alexandria indicates celebration of the Nativity of Christ on December 25. In the third century, the feast of the Nativity of Christ as with the former, was previously mentioned by St. Hippolytus of Rome, who appointed the reading of the Gospel on this day to be taken from the first chapter of Matthew.

In the middle of the fourth century, Furius Dionysius Filocalus composed the Chronograph of 354, in which, for the first time in Western tradition, December 25 was noted as the date of the birth of Christ. In addition, there is indirect evidence that the holiday was celebrated already in the mid-thirties of the fourth century.

The rich homiletic heritage of both western and eastern preachers leads to similar conclusions. So, for example, the Christmas sermon attributed to Pope Liberius, whose pontificate—352-366—falls precisely during the indicated period.

North Africa, one of the greatest strongholds of Byzantine culture, had become creative place of great Christian preachers and theologians, who have not ignored the holiday in question. St. Optatus, Bishop of Milevis in Numidia delivered a Christmas sermon on December 25 of either 362 or 363 A.D., which was the earliest known Christmas homily.

According to Blessed Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, December 25 is the historic birthday of Christ, of God-revealed origin, as chosen by Christ Himself.

Although the North African tradition of celebrating Christmas could most likely have come under the influence of the Latin tradition, the Roman practice itself is clearly presented only in the Christmas sermons of St. Leo the Great, the Pope of Rome, a century later. At the same time, the Feast of the Theophany (Epiphany), celebrated on January 6, meant for Pope Leo not yet the Baptism of the Lord, but the worship of the Magi, which is a revelation of God to the Gentiles—the same as for blessed Augustine. It was an organic end to the festive period, which began on December 25.

Of particular note is the coincidence of the celebration and afterfeast of the Nativity of Christ, celebrated in December, with the pagan holiday of the sun and the Roman January calendar [events] associated with it. Just as the January date of Theophany (January 6) "coincided" in time with a similar holiday of the Gnostics, the December date of Christmas (December 25), was celebrated at the same time as Roman pagan celebrations. This juxtaposition of the Nativity of Christ and the sun, especially when Christmas began to be celebrated steadily on December 25, the third day after the winter solstice (December 22), was a peculiar response-challenge of Christians to the pagan celebration in honor of the Unconquered Sun (Sol Invictus), introduced in Rome by decree of Emperor Aurelian in 274.

In connection with that, Professor M.N. Skaballanovich notes: “The pagan Roman cult celebrated the winter solstice with special solemnity, but not on the day when it took place (December 8–9), but on the days when it became tangible [visible] for everyone, precisely at the end of December. The feast in honor of this solstice was called the day of the unconquered (dies Invicti), that is, the day of the unconquered sun, the sun that winter could not overcome, and which is going towards spring from now on. In one Roman calendar of the fourth century, this pagan holiday is shown on December 25th. It is dedicated to this very day, perhaps because December 18–23 in the Roman cult was dedicated to the celebration of the god Saturn, who devoured his children; that celebration, was therefore of a gloomy character. This sad holiday of the “god of time” was followed by the bright feast of the “god of the sun”, just as our [Nativity] fast is preceded by great holidays.”[8]

The foregoing can be summarized as follows: the celebration of January 6 was well correlated with the most important events in world history—with the creation of the world and with Pascha. Just as the old Adam was created on the sixth day, so Christ—the new Adam—on the sixth day reveals His Divinity after being baptized in Jordan, or at the time of the Divine Infant’s coming into the world. January 6 corresponded to Nisan[9] 6—the day of the creation of the first Adam.

The indicated chronological marks organically fit into the system of Byzantine New Years: January 1, March 1, September 1. The most solemnly celebrated January date (January 1)—a few days after the pagan holiday of the sun. The marked new year was celebrated in Byzantium not only by pagans, but also by Christians. The beginning of time, the annual cycle, which could be associated with the beginning of the world, with the day of creation, at the same time turned out to be identical to the time of the coming of the Savior, the Sun of Righteousness, Christ.

Of course, this holiday was national, not without elements of pagan celebrations. Undoubtedly, Christmas carols date back to Roman calendars.

It is necessary to say a few words about the establishment of the feast of the Nativity of Christ in the Churches of Antioch, Alexandria and Constantinople.

The manuscript of the Syrian Monophosyte theologian Dionysius Bar-Salibi († 1171) contains a scholia explaining the reasons for introducing a special celebration of Christmas, which was established with an apologetic purpose—to refute the pagan holiday of the sun.

The feast of the Nativity of Christ, celebrated on December 25, turned out to be so convincing and important that during the 4th–5th centuries, it was accepted everywhere, not only in the West, but also in the East, including the most distant countries—Syria and Armenia.

The sermons of St. Gregory the Theologian and St. Gregory of Nyssa on two separate holidays of Christmas and Theophany confirm the appearance of these holidays in the Church of Constantinople. So, Gregory the Theologian gave two sermons: on Christmas—December 25, 380—and Theophany—January 6, 381. The separation of the holidays of Christmas and Theophany, approved by him in the Church of Constantinople, is subsequently confirmed in the sermon of St. Proclus of Constantinople (434–446).

The sermons of St. Gregory the Theologian and St. Gregory of Nyssa on two separate holidays of Christmas and Theophany confirm the appearance of these holidays in the Church of Constantinople. So, Gregory the Theologian gave two sermons: on Christmas—December 25, 380—and Theophany—January 6, 381. The separation of the holidays of Christmas and Theophany, approved by him in the Church of Constantinople, is subsequently confirmed in the sermon of St. Proclus of Constantinople (434–446).

In the years 386–388, St. John Chrysostom delivered sermons dedicated to the Feast of the Theophany. In one of them, given on December 20, 386 (or 387, or 388), preparing the people for the feast of the Nativity, the saint called it "the most revered and sacred of all the holidays." In another homily, he testifies that the Nativity of Christ in the Church of Antioch was introduced in the second half of the 70s of the fourth century.

The Alexandrian Church, like other Eastern Churches, initially celebrated only the Feast of the Theophany until the first third of the fifth century.

Most likely, the feast of the Nativity was introduced in Alexandria at the initiative of St. Cyril of Alexandria, shortly before the Council of Ephesus. Paul, Bishop of Emesa[10], preached on the feast of the Nativity of Christ on December 25, 432 in the Great Church. He spoke of the birth of Emmanuel, “Who in His Divinity is free of passions (suffering), and in His humanity suffered [for our sake—Trans.]” but he didn’t even mention the Baptism.

In other words, the celebration of December 25th was established in Alexandria between 418 and 432 A.D.

Thus, a distinct Christmas holiday [separate from Theophany—Trans.] was established in the Church of Antioch no earlier than 376–377, and in the Church of Constantinople at the end of the 370s, with the other churches of Asia Minor following, and later in the Alexandrian Church no later than the early 430s.[11]

The introduction of a separate feast day for the celebration of Nativity in the Church of Jerusalem deserves close revision. It was there that the greatest resistance was rendered to the establishment of the December celebration.

In the middle of the fifth century, Patriarch Juvenal (424–458), having returned to Jerusalem after the Council of Chalcedon, introduced the celebration of Christmas on December 25th here for a short time—moreover, with a focus not on the Latin, but on the Byzantine canon.

However, the Church of Jerusalem soon returned to its former custom, which, in particular, is attested by a Georgian version of the Jerusalem lectionary at the end of the fifth century that references the celebration of Christmas and the Baptism of Our Lord in Jerusalem on the same day—January 6, as well as data extracted from the two most famous hagiographic works of Cyril of Scythopolis (sixth century), “Christian topography” by Cosmas Indicopleustes and others.

The situation of heortological syncretism persisted until around 560/561 when Emperor Justinian wrote a letter “On the Holidays of the Annunciation, and the Nativity, Meeting, and the Baptism of Our Lord,” addressed to the Jerusalem Church under the Patriarch Eustochius (552–563 / 564), lamenting that the dates of the holidays of the Annunciation (March 25) and the Meeting (February 2) are violated there. Referring to the Gospel of Luke (Luke 1: 26–56), Justinian also cited a number of authoritative opinions of the fathers: the Holy Hierarchs Gregory the Theologian, Gregory of Nyssa and John Chrysostom, as well as a text under the name of Blessed Augustine of Hippo, trying to convince Jerusalem to accept a separate Christmas holiday.

These recommendations, however, were implemented after the death of Justinian. According to the liturgists, a separate Christmas celebration on December 25 was introduced in Jerusalem after 567/568.

The Feast in Orthodox Liturgical Practice

Photo: A.Pospelov / Pravoslavie.ru Since antiquity, the day of the Nativity of Christ was numbered by the Church among the Twelve Great Feasts, the Feasts of the Lord, and the Unmovable Feasts.

Photo: A.Pospelov / Pravoslavie.ru Since antiquity, the day of the Nativity of Christ was numbered by the Church among the Twelve Great Feasts, the Feasts of the Lord, and the Unmovable Feasts.

The feast of the Nativity of Christ has a five-day forefeast (December 20-24) and a six day afterfeast, with the leavetaking on December 31.

Evidence of the ancient combination of the feasts of the Nativity and Theophany remaining to present times in the Orthodox Church is the perfect resemblance of the way these feasts come to us. They are both preceded by an Eve, when it is prescribed to fast "to the [first] star." The order of the services on the eve of both holidays, and on the feasts themselves is also exactly the same.[12]

We should here make brief comments about Nativity Fast. It originates from the ancient Christian custom of fasting on the eve of the great holidays, so as to partake of the Holy Mysteries on the holiday itself. But the pious pursuit of the spiritual feat[13] of fasting was not limited to one day. From the works of St. John Chrysostom, it is clear that in his time, the Nativity Fast began on December 20 and, thus, was thus five days long. Some Christians increased the fast to a week or even twenty-one days. And finally, they began to fast, as in Great Lent, for 40 days, that is, from November 14. Such a fasting term is already found in the Hypotyposis of St. Theodore the Studite[14]. The chronological instability of the Nativity Fast was overcome by Patriarch Luke Chrysoberges (1156–1169), when it was established that all Christians fasted before the feast of the Nativity of Christ for 40 days.

Patristic exegesis of the holiday

According to the divine testimony of the Gospel, the Fathers of the Church in their homilies portray the feast of the Nativity of Christ as the greatest, universal and most joyful, [aside from Pascha—Trans.] which serves as the beginning and foundation for other holidays. Venerable Ephraim the Syrian, and Holy Hierarchs Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, Gregory of Nyssa, Ambrose of Milan, John Chrysostom, among others, speak of this.

St. Ambrose of Milan emphasizes: “The more one loves Christ, the more diligently must be the keeping of His commandments; so that He may see that we truly believe in Him, so that on the day of His Nativity, we will shine when we try to appear to Him, with temptations of faith undone by mercy, and adorned with good morals. And He will be in greater joy, the more chaste we become. And therefore, a few days before, let us cleanse our hearts, so that we will be of a pure conscience as we decorate our souls; and so cleansed of all impurities, we will celebrate the coming of the Immaculate Lord—Who was born of the Immaculate Virgin—so that we will celebrate Christmas as immaculate servants. For whoever is defiled and unclean on this day, he thus cannot celebrate the Nativity and Advent of Christ. Although he will be present at this celebration with his body, he is far removed from the Savior of the world by spirit: They cannot have any fellowship—the wicked with the Holy, the lover of money with the Merciful and Charitable One, an adulterer with the Virgin. If the unworthy enters into this communion, he unknowingly prepares for himself greater condemnation… So, brethren, in meeting the day of the Nativity of Christ, let us cleanse ourselves from all iniquities; so that we will unlock the treasures of our various gifts, so that on this holy day, the strangers could receive from them what is necessary for themselves; let the widows be nourished; and may the poor be dressed.”[15]

The Holiday in the Western Tradition

For the Western tradition, it is important that believers commemorate the event of Christmas itself, but nevertheless, to celebrate all which comes from it, which is to say, to magnify the One who was born, from the perspective of current times.

For this reason, the holiday was not at first called natale Domini—the feast of the Nativity of the Lord. The texts of the ancient Roman Christmas mass reflect only in a small part, the events that occurred in Bethlehem, but in every way emphasize the pre-eternal Word of God the Father was clothed in the flesh. According to the sermons of Pope Leo I, in Rome in the fifth century, the key component of the feast of Christmas is fact of Christ becoming man, which is carried out in the events of the Annunciation and the Nativity.

The Roman genesis [Nativity—Trans.], researchers believe, also possessed three Nativity masses, which are “served at night (in nocte), at the morning star (in aurora) and during the day (in die)”.[16]

The oldest of them, initially the only one, was the papal mass, which was served during the day, and the later one was celebrated at dawn break. Its station, (which was connected with the so-called station churches[17], from where the solemn procession transferred to another church), was made on Palatine Hill, where the residence of Augustus was located. There was a church there in the name of St. Anastasia, whose memory is celebrated on December 25.

The aforementioned masses subsequently entered into the sacramentary[18] and, through the liturgical practice of Rome, spread throughout the West. At first, however, three different stops were not prescribed as mandatory. The trilogy of services was also adopted by the [Roman] Missal of 1970, which also retained the octave present in Latin practice, as is known, only at Easter and Christmas.

The gospel of the Nativity of the Lord sets the tone for the night Mass (Luke 2: 1-14). During the morning Mass, the reading of this gospel text continues (Luke 2: 15–20). The prologue of the Gospel of John (1: 1–18) is the basis of the third Mass.

The Christmas Liturgy also includes the “Мissa vigilia”, the evening mass on December 24, after which the genealogy of Jesus is read from the gospel (Matt. 1: 1-25).

In Catholic churches starting from the thirteenth century, small niches were arranged, in which scenes of the Nativity of Christ were depicted with the help of figures made of wood, porcelain, and painted clay. Over time, nativity scenes were put not only in churches, but also in homes before Christmas.

They stood up for several weeks, until Candlemas[19] on February 2. Popular home nativity scenes depicted a cave with the Divine Infant Jesus in a manger, next to the Mother of God, Joseph, an angel, and the shepherds who came to worship, along with animals, most commonly oxen and donkeys.

In earlier times, scenes from the gospel in Catholic countries were acted out by the parishioners; these folk performances were later moved to the public square. Christmas holidays are marked by a combination of Church and folk customs.

In Catholic countries, there was a well-known custom for children and young people to go from home to home in masks and animal skins, with songs and good wishes, similar to koladky [Ukrainian Christmas caroling—Trans.] In response, young people received gifts: sausage, roasted chestnuts, fruit, eggs, pies, and other sweets. This custom was repeatedly condemned by Church authorities, it was not consistent with strict [fasting] canons; gradually, this custom began to be practiced only among relatives, neighbors, and close friends.

Iconography of the Feast

The iconography of the Nativity of Christ developed gradually, as well as the liturgical practices of the feast but its main features were already outlined in the early Christian period.

The iconography of the Nativity of Christ developed gradually, as well as the liturgical practices of the feast but its main features were already outlined in the early Christian period.

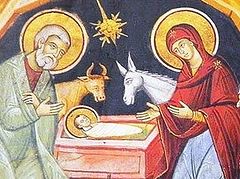

The oldest surviving images of the Nativity date back to the fourth century. In the catacombs of St. Sebastian in Rome, a swaddled Infant is represented lying on a bed[20], next to the virgin with her hair in an ancient [possibly anachronistic—Trans.] headdress.

The distinctive features of the images of the Nativity of Christ on early Christian sarcophagi are images of the scene not in a cave, but under a kind of canopy, and the Mother of God does not recline on a bed, as in later depictions, but sits next to the Baby. The Savior's manger is surrounded by animals—an ox and a donkey—as a fulfillment of Isaiah's prophecy: The ox knoweth his owner, and the donkey his master's crib: but Israel doth not know [Me[21]], my people doth not consider. [Isaiah 1:3]

The icon of the Nativity on the throne of Maximian, Archbishop of Ravenna in the middle of the VI century, is noteworthy. The throne is decorated with a large number of carved ivory plates. In one of them, a Baby is lying on a bed made of stone blocks, next to him is an ox, a donkey and Joseph the betrothed, and above—the star of Bethlehem. Before the bed reclines the Mother of God, to whom the woman addresses, showing her right hand. The story goes back to the twentieth chapter of the Protoevangelion of James, which tells of Salome doubting the purity of Our Lady. After that, the hand with which she had touched the virgin withered. Salome was healed by touching the Savior.

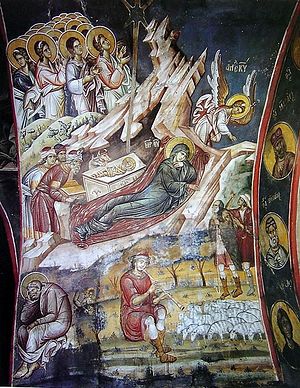

On one of the Monza ampullae (sixth to seventh centuries), which served as small flasks for the transfer of holy water or oil, has a depiction of the Nativity of Christ engraved on the center including various other holidays. These relics reflect important features of Byzantine iconography, as compared with early Christian—the canopy is no longer depicted, the exit from the cave is visible in the background, the star is located in the center above. Joseph sits not far in a thoughtful pose, Our Lady reclines. From then on, She is always portrayed with a halo.

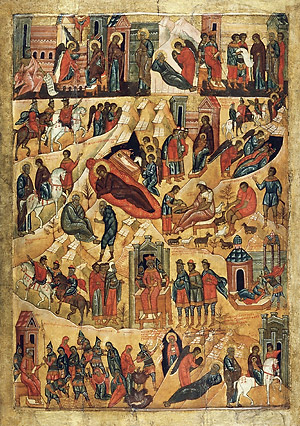

On the whole, the iconography of the Nativity of Christ took shape by the seventh century.[22] After a period of iconoclasm, the image will often be depicted in iconography, miniature, and decorative art based on a common outline. The permanent elements of the composition are the cave, and the Star of Bethlehem, which brought the Magi to Christ. Perhaps this is why on some late Russian icons and frescoes (for example, on the 1680 fresco from the Church of Elijah the Prophet in Yaroslavl) the Nativity scene is crowned by the figure of a flying angel with a star in his hands.

The main imagery of the Nativity (the image of a swaddled Baby in a manger in a cave, animals at a manger, the reclining Mother of God, and Joseph sitting) in various works will be, especially in the eighth to ninth centuries, complemented by the image of angels glorifying the Lord, the scene of the annunciation to the shepherds, scenes of the travel and the adoration of the Magi, and the ablution[23] of the Baby.

While the angels, shepherds, and magi are described in the Gospel (see: Matthew 2: 1–12; Luke 2: 6–20), then the written source which caused the iconographers to create the scene of the ablution of the Infant Christ has not been established. It is only known for certain that for the first time, this aspect of the iconography of the Nativity, which later became established is found in the Christian art of the Western world, and is present in the oratorio of Pope John VII in Rome (between the seventh and eighth centuries).

It is extremely rare in the icons of the Nativity of Christ, that the image of the prophet Isaiah is depicted, predicting the birth of the Savior from the Virgin. The figure of an old man in skins talking with Joseph (and sometimes with the Mother of God herself) also raises many questions.[24]

In Rus’, icons of the Nativity were extremely popular. Of course, Russian icon painters followed the Byzantine iconographic scheme, but supplemented it with various details. Already by the eleventh to twelfth centuries, the Nativity cycle almost always appeared in an expanded version, which included, for example, not only the worship of the Magi, but also their journey following the star of Bethlehem. See, for example, the monumental painting in the cathedral of the St. Anthony Monastery in Novgorod.

In connection with the review of monumental ensembles, it should be noted that in Byzantine and Russian painting, the theme under consideration was given a special place. Most often, the Nativity of Christ was depicted paired with the Dormition of the Theotokos: the themes were opposite each other, for example, on the southern and northern walls. This symbolic contrast between birth in the flesh, and new birth after death for life in heaven, was emphasized by similar iconographic motifs. In the Nativity, the Savior lies swaddled in a manger, and in the Dormition, Christ holds in his hands the soul of the Mother of God, presented in the form of a swaddled baby. Just as the Lord entrusted Himself to the Blessed Virgin on Christmas night, the Mother of God entrusted her soul to Christ in the Dormition. A clear comparison in the church scenes of these themes is significant, because they illustrate the beginning and end of the history of salvation, from the Incarnation to the ascension of the incorrupt body of the Mother of God.

Of particular popularity in Russia were the icons with the image of the Synaxis of the Most Holy Theotokos. This feast is celebrated the day after Christmas, and is closely related to the meaning and nature of the service. On December 26 (January 8, in the new style), Christians honor the Blessed Virgin as the Mother of the Son of God, who served the mystery of the Incarnation.