Today’s scripture readings and hymns present two themes.

First, we have the Publican and the Pharisee.

And second, we have this commemoration of the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia. And it’s the latter theme I’d like to give our attention to today.

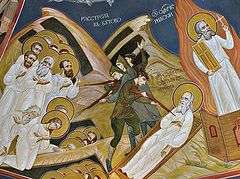

You’ll see, in the middle of our church, an icon depicting row upon row of martyrs. Some—in the foreground—are identifiable (Tsar Nicholas and his family). They’re accompanied by specific hierarchs, priests and righteous women (including St. Elizabeth).

But after the first few rows, you’ll begin to see only heads with haloes—and beyond that, only the tops of haloes themselves. What this “disappearance into the distance” means, is that the number of those who were led as sheep to the slaughter in Communist Russia, is too great to properly measure—that beyond those we know, are an even greater multitude of those known only to God.

And that’s a fair summation of all who perished in the gulags, firing squads and forced starvation of history’s largest atheist experiment gone awry.

The scripture readings for this feast also express the scale and intensity of this great witness to Christ in our modern times.

We could even boldly say that the Romans passage—addressed to the first generation of those who’d suffer for Christ—finds its ultimate fulfillment, in being addressed to these who recently suffered in even greater numbers than under Rome.

When Paul writes, “Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword? As it is written, ‘For thy sake we are being killed all day long; we are regarded as sheep to be slaughtered’—these words require no leap of imagination to see as being fulfilled in the sufferings of the faithful in Russia.

Likewise, the Gospel. When Christ warns, “They will lay their hands on you and persecute you,” and “You will be delivered up even by parents and brothers and kinsmen and friends, and some of you they will put to death,” He could easily have spoken of komissars and secret police, into whose hands family and friends considered it their patriotic duty to betray their own, as enemies of the people.

Today, we’ll zoom in and focus on one of these innumerable martyrs. And it won’t be anyone in the first rows of the icon—but in the far off distance—the top of whose halo you probably don’t even see.

I’ve spoken before of New Martyr Konstantin, whose relics and icon we have over here. Numbered with him in glory, is New Martyr Pavel. Pavel Lazarev was a simple priest, serving in the trenches of parish life—who had a short time to decide how to spend eternity.

He was born in 1877, in Siberia. Following his mandatory military service, he became a choir director—and after marriage, a priest. His parish was in Primorsky Krai (that’s right across the Pacific Ocean from us, bordering China).

Father Pavel was known for collecting food for the hungry, and teaching the basic catechesis called God’s Law (simple doctrine, and rules to live by). He was, by all accounts, an ordinary priest—who under ordinary circumstances, we wouldn’t be discussing now.

But his times were not ordinary. On Pentecost Eve, 1919, a parishioner warned Fr. Pavel that a red partisan unit was in the area, and would arrest him that night unless he fled. Should he hide with relatives, and escape being led as a sheep to the slaughter?

Instead, Fr. Pavel chose this as an opportunity to deserve the name of Christian. He was waiting for the soldiers when they came. They allowed him a few moments to pray, venerate his icons and kiss his wife and children goodbye. From here, Fr. Pavel was taken for interrogation.

The partisans made him an offer he couldn’t possibly refuse: He’d be allowed to go free, on the simple condition that he publicly declare that as a priest, he’d always deceived the people by proclaiming a false entity known as “God.”

He was then to publicly remove his cassock and cross, and be a priest no more. Thus, he’d be allowed to return to his family. But he couldn’t, for the sake of more time here, part with them forever. So, better to die here, and live.

Installation of memorial cross at site of execution of Fr. Pavel Lazarev in village of Nikitovka (2017). Photo: vladivostok-eparhia.ru Father Pavel was taken into the woods. And on Pentecost day, he was shot and left to die.

Installation of memorial cross at site of execution of Fr. Pavel Lazarev in village of Nikitovka (2017). Photo: vladivostok-eparhia.ru Father Pavel was taken into the woods. And on Pentecost day, he was shot and left to die.

Among his few surviving words, recorded by his wife, where these: “I clearly see that the people’s task is not to remake the state system, but to work on the human person, and to be better yourself, and even to suffer for the truth.” This he did, suffering for the Truth, who is Christ.

But, Fr. Pavel’s story doesn’t end here, because the legacy he bequeathed continued. As Russia descended further into darkness, his son Eugene escaped, first to China, then Yugoslavia.

And when Yugoslavia fell to another darkness called Hitler, Eugene received a strange proposal, along with thousands of other Russian émigré captives: to join the Nazis on their march against Stalin, and free their homeland from Soviet tyranny.

It may be difficult to understand how, for many Russian exiles, Stalin was even worse than Hitler. But Eugene accepted. And thus, he met his wife.

Helen was among Russians who greeted the Germans as liberators. The first thing they did in her town was re-open the church. And while cleaning this desecrated temple, Helen realized she was enamored of the White Russian officer overseeing the job, who was Eugene.

Germany’s invasion soon fizzled, however, and Eugene and Helen found themselves fleeing across a collapsing front. On the way west, they wed at a Russian church as mortars fell around.

At war’s end, they barely escaped being repatriated to Russia—unlike many unlucky comrades, who ended up summarily shot.

From Germany, they came to America and ultimately: Pueblo, CO, where Eugene served as choir director—and helped keep the parish going during tumultuous years of infighting and decline.

And this story I heard over many visits with Helen, as her pastor. Eugene had long since reposed, but I felt like I knew him through her, and the love people still had for this pious, gentle man—the image of his sainted father.

Although the Newmartyr Pavel was canonized only last month, he’s been venerated by Pueblo’s faithful for years (with a hand-painted icon on the wall)—because of the legacy he passed to his children: of (as he put it) struggling “to work on the human person, and to be better yourself, and even to suffer for the truth.”

This legacy we should all strive to receive, from the witness of that “greatest generation” of Orthodox: the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia.

Fr. Barnabas Powell is the priest at the St. Katherine Church (OCA) in Kirkland, Washington.