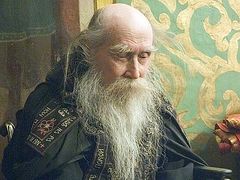

January 30 was the funeral service for the spiritual father of the Danilov Monastery in Moscow, Archimandrite Daniel (Voronin). The newly-reposed is remembered by his spiritual child Archpriest Alexander Tikhonov, the rector of the Church of the Prophet Elias at Vorontsovo Field.

The youth went where it was interesting

Archimandrite Daniel (Voronin) I remember I was twelve when I arrived at Danilov Monastery. There was still a children’s colony there at the time. I was told: “We’re going to put you in here! Just come here, and you’ll stay!”

Archimandrite Daniel (Voronin) I remember I was twelve when I arrived at Danilov Monastery. There was still a children’s colony there at the time. I was told: “We’re going to put you in here! Just come here, and you’ll stay!”

I walked around the monastery. I went to the Church of the Resurrection. It was in complete ruins. Where the Danilov Hotel is now, there was a reinforced concrete fence, and behind it, a dump. Equipment from building the metro was dumped there. Everything was overgrown. Where the Patriarchal residence is now, there was a branch of a refrigerator factory. Utility trucks were constantly coming in and dropping off boxes. Something was being loaded and unloaded. It was a lot of hustle and bustle. But everything was somehow lifeless, joyless. The spirit was so stale…

Then I heard: “Danilov Monastery was given to the Church!” This happened in the summer of 1983. I went there. The first person I saw there was Fr. Raphael (Shishkov), then either Archpriest Paul or the already-tonsured (but before the schema) Fr. Alexei. The churches in the monastery weren’t active yet. Only the current Church of St. Seraphim of Sarov was already equipped for a chapel. There, behind a desk, stood the future schemamonk. Candles and icons could be bought. There was no question of any books at that time. The entire Tradition was passed on by word of mouth at that time.

You could already feel that the life was different there. It had all dissolved into the air somehow. But they still wouldn’t let me in (I was a high school student, and they were afraid the authorities would find some fault with them), although the youth were already being drawn to the monastery, especially on weekends. We were ready for any work. We hung around there, in hopes that they’d put us to work.

I was simply exultant then: I was in an environment that was very dear to me! I was fully immersed in an atmosphere of rebirth. I dropped out of school. What was happening there was obviously the most interesting thing going on. I went to the monastery every day on my vacations.

I remember, in September, I returned to school and began to “recruit” my classmates. Two or three went with me a few times, but I could see that they were under pressure at home. I had somehow managed to settle everything with my parents, and they would later go see Fr. Daniel, and they really respected him. Batiushka then assisted in the Baptism of my cousins. Meeting him became a defining moment for me and my family in many ways.

How Fr. Daniel became the first monk of Danilov Monastery

I noticed Fr. Daniel at once. There were few brothers then. The monastery was headed by Fr. Evlogy (Smirnov)—now a retired hierarch.

They weren’t serving Liturgy in the monastery yet then. The monastery churches were in a dreadful state. The brothers got a small bus and would go to services at the more or less preserved Donskoy Monastery. I remember the driver was a wonderful man—Vladimir Ivanovich. In general, amazing people started gathering together.

Do you know how Fr. Daniel wound up in Danilov Monastery? Later, while already studying in seminary, I got into a conversation with Fr. Jonah (Karpukhin), who is now also a retired hierarch. He told me:

“Ye-e-e-s… Fr. Daniel! I remember him! His name was Viktor Voronin. He graduated rom the Moscow Seminary here. All his classmates had already left, but he didn’t leave for a long time; he was hanging around the Lavra. He was thoughtful. I saw him one time:

“Viktor, why aren’t you leaving? Are you going to enter the Academy?”

“No…”

“Are you thinking of getting married?”

“No.”

“Going to a monastery?”

“Yes, I would like to go to a monastery…”

Fourth from the left—Novice Viktor Voronin, far right—Metropolitan Alexei (Ridiger), the future Patriarch

Fourth from the left—Novice Viktor Voronin, far right—Metropolitan Alexei (Ridiger), the future Patriarch

And just then, the door to the Academy building where we were standing opened and Fr. Evlogy came in. He had just been appointed abbot of Danilov Monastery.

“Oh! Fr. Evlogy, come here!” I yelled to him. “Here’s your first monk!”

Fr. Evlogy asked him: “Do you agree to come to the monastery?”

“Yes, I’ll come.”

And that was it!

Thus, Fr. Daniel became the first resident of Danilov Monastery.

Monastic bartering

Archpriest Alexander Tikhonov This is how we met…

Archpriest Alexander Tikhonov This is how we met…

They were doing repairs in the only active chapel then, of St. Seraphim of Sarov; they were painting something. I worked there too, carrying things in, carrying things out. Then I was given a pretty responsible obedience. I already had bad vision then, but because of some childish folly, I was shy about wearing glasses. One time, I went to report something, and I was talking and talking… And my “boss” was squatting, calmly painting the wall. He was listening attentively, but half-turned away. Once I said everything, he turned around… and I saw—Fr. Daniel!

“Oh,” I said. “I screwed up.”

He just smiled: “Or, maybe not…”

Thus, quietly, Batiushka became my spiritual father. It was sometime in 1984 that we first came into contact.

Batiushka was appointed as the cellarer then. He was in charge of purchases and cooking. He was very conscientious about everything. All the cooks loved him very much. Everyone was nourished by and confessed to him. What amazing people were gathered there then! Deeply religious, active Church people. There was a handmaiden of God Tatiana, now Nun Mitrophania at the Elevation of the Cross Monastery in Domodedovo, near Moscow. This summer, when Batiushka was already sick, I went to see her and told her about it, and she said: “I know! I’ve been sobbing for days!”

Fr. Daniel cannot be forgotten. Everyone who met him will remember him forever. Such a presentiment of eternity, given to use already in the experience of these quickly-flowing days. In the monastery, spiritual connections are always actualized above all.

How we all tried to help Fr. Daniel even then. There was such a purity in him—it was pleasing to God: unclouded joy! I was always hauling heavy boxes for him. Something would be unloaded, moved, unpacked… That’s all external. But inwardly—you would just ladle joy from being with him! It’s a kind of barter, where your mite is meager compared to what you get.

Following closely—extreme in spiritual movement

Batiushka was soon chosen as the confessor for all the brethren. A most worthy choice. He’d found his place. I don’t remember a single brother in the monastery who would have spoken of him poorly, with resentment or indignation, because Batiushka approached any obedience with great responsibility. He was demanding to himself, but merciful to others. So he turned out to be a confessor—not a father, but rather a mother. With such sensitivity he took us under his wing! Especially those who were newly-tonsured. They would sit there in the altar [the brothers would stay there for three days after their tonsure—in the Holy of Holies—O.O.], and he would say: “Oh, I have to go visit the newly-tonsured fathers.”

He would go and read some prayers with them. He would take them to trapeza and escort them back.

He himself was tonsured by Fr. Evlogy. It was the first tonsure in the monastery. He was tonsured together with Fr. Raphael. Viktor Voronin was named Daniel, in honor of the holy Right-Believing Prince Daniel of Moscow. And Fr. Paul Shiskov was named Alexei, in honor of St. Alexei, the Man of God. Later, at his tonsure in the mantle, Fr. Daniel received St. Daniel the Stylite as his Heavenly protector, and Fr. Alexei—St. Alexei, Metropolitan of Moscow (becomes Raphael later, in the schema).

All the following years, being already a metropolitan, Vladyka Evlogy greatly respected Fr. Daniel. And how he revered the elder clergy! Whenever he had to go somewhere, Fr. Daniel also listened and asked the elder priests questions with great interest: “How did this and that happen before? How did they pray? How did they serve?” Tradition was important to him. Succession. The path is narrow (Mt. 7:14),and dangerous—those who seriously think about salvation try to follow experienced ascetics closely. They realize all the responsibility and the price of a mistake. All the moreso because others are following you.

It's a pity that now no one cares about any of this. But he knew that without this gear—this safety net—connecting us to our predecessors, there was no way.

“I’ll at least read the Gospel”

He would go to church every morning and evening. To every service! He was always ready to fill in—If someone got sick, someone had to go somewhere… Like a lifesaver, he would serve instead of the appointed hieromonks. He himself didn’t go on vacation—he let the others rest.

Pilgrimage to Valaam, 1990. Frs. Daniel and Raphael (Shishkov) on the deck of a ship And if he did get out, it was only to holy places. Sometimes he would take someone from among his spiritual children with him. I remember going to Valaam with him. He didn’t relax at all on trips…

Pilgrimage to Valaam, 1990. Frs. Daniel and Raphael (Shishkov) on the deck of a ship And if he did get out, it was only to holy places. Sometimes he would take someone from among his spiritual children with him. I remember going to Valaam with him. He didn’t relax at all on trips…

If he didn’t have to dawdle about with anyone, he would greatly increase his prayer. When he went home, to the Ryazan Region, to his native region, he would break out a little—he would close himself up in his parent’s home and try to live like a hermit there for a bit—in contemplation and increased prayer.

He had a special internal connection with St. John the Theologian Monastery in Poschupovo, which was never interrupted. He was prayerfully close to his fellow Ryazanians—Vladyka Simon (Novikov), then the ruling hierarch of the Ryazan Diocese, and he greatly revered Fr. Abel (Makedonov), Vladyka Barnabas (Kedrov)—also from Ryazan. None of them fought alone on the spiritual front—they supported one another.

Before seminary, somewhere around 1988, I remember I worked in Danilov Monastery, on guard at the church. My duties in particular included opening the church in the morning and closing it in the evening. Even then, Batiushka would hear confessions well past midnight. I would be falling off my feet, and I would start walking from corner to corner so as not to fall asleep.

“Alexander, come on, leave me the key,” I would suddenly hear. “I’ll close it myself. Go rest; get some sleep.”

And he would stay for a long time! And in the morning, you’d see him coming to the early Liturgy! When did he sleep? Did he sleep? He also had to read the rule for Liturgy. Then at the late Liturgy I’d see him standing and talking with someone… Like a mother! He nursed everyone spiritually.

I remember, one time Batiushka was so tired, completely exhausted. He could barely stand on his feet. And then people started pouncing him:

“Batiushka, we need Unction!”

It was far to go... Someone else would have found a ton of excuses, but he said: “I’ll at least read the Gospel [there are seven Epistle and seven Gospel readings in the Unction service—O.O.].

It was the same if someone had to commune—he got ready and went.

Repent and forget! Guard your eyes and ears from now on. And try to pray

Fr. Daniel was a reliable person. Unfortunately, many people abused this trait. He was simply harassed by crowds. Although I know it for myself, others probably felt it too: They wanted to be near him. Therefore, he was sometimes pestered even with absurd questions; it didn’t matter what they were asking—they just wanted to be with him. Such a soothing spirit emanated from him—the grace of God! It was difficult to pull yourself away; a well-known effect of being with a spiritual person.

Batiushka would be walking from the trapeza to his cell and it would last for hours: One person would come up to him, then a second, a third, and so on. Batiushka listened to all of them, he prayed, and he answered.

Batiushka was a comforter. It was easy to confess to him. He never imposed any heavy rules, penances, or burdens grievous to bear (cf. Mt. 23:4). You could say anything to him.

About confession, Fr. Daniel instructed: “You have to repent and forget! Some people repent and then pick the wound open again… No, don’t do that. Repent and forget.”

Batiushka always allowed the person himself to speak out and accuse himself in confession. Even if you were thinking of hiding something, you would involuntarily say it, putting you in a stupor—and he always had answer for you. And he would continue unpacking your life. All of our sins were in his sight. He would pray with you and sigh a little.

Later, I would send my parishioners to him if someone had a seemingly unsolvable situation. He reconciled many. He would even go see people specifically for this. He refused no one.

He instructed:

“The times are such that you need to guard your eyes and your ears (so as not to hear or see any filth). Try to pray all the time.”

“Batiushka, you know, sometimes my prayer is so worthless: I talk with my tongue, but my head doesn’t know what I’m thinking,” I could complain to him sometimes, and he would respond:

“Pray all the same! You know, it’s like when milk is churned into butter: They stir it and stir it up in a pitcher… That’s how prayer is. You pray, whether it’s on your tongue, in your heart, in your memory, in your mind, even if it’s unconscious; but you build a habit this way. Pray! Let’s try!

The taming of the tempest

And what a gift of discernment he had! How this quality is lacking in people now…

You would ask him about something, tell him something. And he would stand, eyes closed. “Is he sleeping or something?” No, he’s not sleeping! He’s listening to you, fathoming, praying. He would open his eyes—such a concentrated look.

“Well, my friend, it’s better to do this.”

I remember, I had a choice to make: I was invited to serve in two different churches. The first—to Fr. Dmitry Ivanov in the Church of St. Dmitry of Rostov in Ochakovo (near where I was living then, in Troparevo); the second—the Church of Sts. Florus and Laurus on Zapetskaya Square.

I asked: “Batiushka, where should I go? I like both…”

Batiushka prayed.

“Well, my friend, go to the one closer to us—to the monastery” (meaning to the church on the square, Sts. Florus and Laurus).

There was another case: As soon as I graduated from seminary, they began to call me to the Moscow suburbs—they’d practically already set aside a place for me in one parish. I had taken a liking to the place myself. At the same time, I was a native Muscovite: How could I leave Moscow? Though they were so persistently persuading me to go there, or you could even say they’d already persuaded me…

“No, Alexander,” Batiushka suddenly said, cutting me off. “Don’t go out from under the direct omophorion of His Holiness in the Moscow City Diocese. Stay here. It will be hard for you there. That’s what you’re saying now. But if you go there, you’ll start pining for Moscow and it will be hard for you there. Stay, serve here.”

I accepted Batiushka’s direction then. And then again, doubts still tormented me. I was standing one time at the grave of the not-yet-canonized Fr. Aristokly at Danilov Cemetery—within me there was a storm: How could I be sure? And the Lord gave me a sign—He calmed the sea, to be exact (cf. Mt. 8:26)—I don’t know, perhaps by the prayers of my spiritual father. They served a panikhida there then, and one handmaiden of God put a stack of icons on the grave. The people quickly snatched them up.

And she upbraided me: “Why are you just standing there? Why aren’t you going up there? Go, take one! Oh, there’re no icons left, but here—take this picture from the Elder’s grave!”

I took it and looked: the city of Moscow! And above it—a host of saints. Everything became clear.

Everything that was Fr. Daniel’s was ours

I was already working in the monastery when it was later given Dolmatovo as a subsidiary farm. I was given the obedience of looking after everything there, and working in the apiary. We first went there in 1989, immediately after Pascha: the brothers, headed by Fr. Daniel, and me too.

First Pascha in Holy Trinity Cathedral of the revived Danilov Monastery, 1985. Hieromonk Daniel in the center

First Pascha in Holy Trinity Cathedral of the revived Danilov Monastery, 1985. Hieromonk Daniel in the center

We arrived… It was creepy, in complete ruins. Overgrown. You couldn’t get through; it was like a jungle. There was once a manor home in the hollow, then it was converted into a school under the soviet authorities, and when it became known that this building, which had long been empty, was to be given to the monastery, someone came and set it on fire. Everything was blackened… It crumbled.

We inspected the place. There was one old man there. He had a patriarchal look: a long beard, but at the same time, pitiful. His name was Misha [Michael] Kirillov. He was a poor old drunk. But this grandpa had such a pure heart! Guileless and sincere. His house was also burned down. He went into the woods to pick mushrooms, and when he returned—there was no house. They wanted to send him to an old folks’ home, but he refused. He settled in nearby, in the shed. He heated it in the winter as much as he could. It was freezing there. His legs were frostbitten. The toes on both feet had been amputated in the hospital. He started dragging any household items people threw out into the shed. The neighbors started chasing him out.

“Grandpa, why are you crying here?” Fr. Daniel asked him when we found him there, not far from our ruined church.

He was sitting there among the garbage he’d gathered, just like a child.

“Well,” he sniveled, “they kicked me out. I have nowhere to go.”

“Don’t cry,” Batiushka said, encouraging him. “We won’t let you get hurt. Stick with us!”

Thus, he became our helper.

“How’s Misha doing there?” I asked Fr. Daniel later, when I had already started seminary.

“Misha’s doing well. Whatever the problem, he runs and solves it immediately. He’s grafted himself onto the farmstead. Our man!”

Everything that was Fr. Daniel’s, was ours. He tried to acquire the Kingdom of Heaven for everyone.

Radonitsa, 1985. Fr. Daniel is the hierodeacon with a candle and censer; the future Archpriest Alexander Tikhonov is third from the left

Not the item but the memory of the man was valuable

He had a huge flock. So many good, cultivated, bright people. They were all like family. Batiushka carefully led each and every one of them, sponsoring them—he didn’t just get someone accustomed to the Church life and then say, “Okay, figure out the rest yourself.” No, Batiushka advised everyone with something according to their measure, leading them further and further. There can be no stops if it’s a truly spiritual life.

Pastors have different kinds of spiritual children, but with Batiushka, everyone was obedient. You have to be able to dispose your soul this way.

And Fr. Daniel really loved the brothers of Danilov Monastery.

I had to go help Batiushka in his cell. He used to live in the “hospital” building, to the right of the entrance of the monastery. It was such a ramshackle space, with rotten beams—ready to collapse at any minute. He somehow paid no attention to anything external. He just prayed and prayed. Later, when reconstruction began, I helped him move his belongings to a new cell. He had very few things. Batiushka simply gave us young guys the key to his cell.

I went there, and I remember thinking: He doesn’t have any time—I’ll tidy up. I started to sweep, and I saw that he didn’t even have a bed! He had two nightstands with a piece of particle board laid on them, and a very thin mattress on top…

I remember he also had a wooden bench there. It was in the old cell too, and when he moved, he was concerned about the bench. I started to balk: “There’s nowhere to put it in the new cell…”

“No, we have to take this bench,” Fr. Daniel said, suddenly starting to worry. “It was made by a really good man (and it really was made surprisingly well). “We can’t forget that grandpa!”

Apparently, he’d already reposed by then… It wasn’t the item itself, but the memory of a man that was dear to Batiushka.

Batiushka placed a waist-length icon of the Prophet Daniel on the bench. Besides that, he had perhaps only a bookcase and a desk, also covered with books. There was a kiot [icon case] hanging on the wall with the candle and cross from his tonsure. The icons in his cell were very simple. And the stuff that people brought him—once an entire home iconostasis, ancient icons (someone died and their relatives gave him the icons)—he immediately gave it all away. As soon as someone liked it, Batiushka immediately handed it to them! He begrudged nothing.

His spiritual children always brought him presents. He kept them all in the hallway—he didn’t even bring them into his cell. Then the brethren would come to him: “Batiushka, may we?”

“Take them.”

He wasn’t attached to things; he sought no comforts for himself. He was ready to give everything away. People would bring him money in envelopes, and it was all given away, to the brothers—some for a trip, others for treatments. Batiushka took no care for himself. He didn’t feel sorry for himself.

Down the steps and back up again—not a workout, but an ascetical exercise

He was a faster, a man of prayer. He took nothing at all into his mouth in the first week of Great Lent. I remember, I brought him a modest ration from the trapeza, and he told me sharply:

“Alexander, take all of this back. I didn’t ask you for it.”

But he was condescending with others regarding fasting and other ascetic feats.

“The main thing,” he would say, “is that the vapors from all these diverse foods don’t obscure your mind and reasoning.”

In our nature, everything is interconnected—someone eats to satiety, and he flies off the handle, screwing up everything. All you have to do is be more restrained in the basics—in food, for example; somehow outwardly restrain yourself. I remember we, the young guys, were flying up the stairs in the brothers’ dorm—we weren’t going two steps, but four steps at a time. And Fr. Daniel was at the top:

“Well, my friends, go back down again, go outside, and come back up calmly.”

By the way, this also teaches inner staidness, so necessary in the spiritual life.

Batiushka was usually unseen and unheard. He could suddenly spring up right in front of you. He would go into church unnoticed, stand off to the side and pray. He never declared himself, never displayed himself before anyone. He was a modest, quiet man of deep spiritual life.

In some difficult cases, Batiushka could redirect you to Fr. John (Krestiankin), for example. I remember, I went to him with some confusing question…

“Oy,” Batiushka said, “Why didn’t I take you to Fr. John? I should have taken you to Pechory. I just went there. Why didn’t I think to take you with me?”

You could tell Batiushka John about Fr. Daniel, and he would immediately say: “We pray for him; we remember him.”

There was a spiritual connection between them, as between all ascetics, probably.

I remember Fr. Daniel used to get tired and look off somewhere into the distance, as if he was seeing some secret of God. The transcendence of being could be felt with him. He was constantly in prayer—gathered deep within himself. He never said an extraneous word.

He simply didn’t chatter. He didn’t laugh. He was prudent, calm. If someone started causing a panic, Batiushka would calm everyone down: “Let’s pray, brothers. Calmly, without fuss.”

Then he would begin to thoroughly analyze the question that was bothering someone:

“What if it’s like this? Or like this?”—in some ways just like the method of Fr. John (Krestiankin).

Batiushka would also reflect with you. He never gave any recommendations to the gathering. Everything was done with the deepest discernment.

He always recalled the words of St. Seraphim of Sarov: Acquire the spirit of peace, and thousands around you will be saved. You don’t need to rush about, to imagine something extraordinary, to be resentful: How could it not have happened as I wanted?! Acquire the spirit of peace! Then everything in your life will go God’s way.

Fr. Daniel himself acquired the spirit of peace. We mustn’t lose this saving trajectory now: Follow in his footsteps—to God.