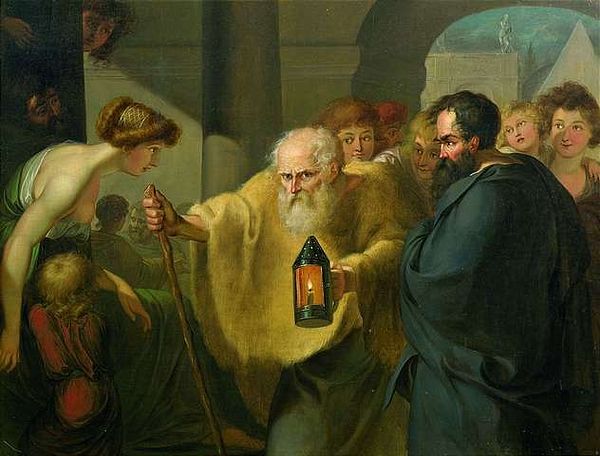

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. Diogenes Searching for an Honest Man

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. Diogenes Searching for an Honest Man

Human beings tend to seek out other human beings. But, if they look deep into their souls, they will realize that they are in search of God even more so. At all times and on every continent our common task is to encounter Him and to respond to His love. What is the easiest way to do this—by living among people, or by withdrawing from the world? Where can a person who truly loves God find real freedom?

In order to sin less, one should talk less: silendo nemo peccat. To be completely silent amounts to the same thing as escaping from people, since being in their company presupposes inevitable communication, getting used to one another, adjusting oneself to others, and entails a hidden exchange of sins and virtues. One cannot save one’s soul among people who do not want to be saved, which is why Arsenius the Great heard the following words: “Arsenius, flee from men and you will be saved”. 1

When one doesn’t eat or eats almost nothing, one weakens the links with the earth. Through the stomach—or, to put it more crudely, through the belly—we are connected to the visible world like a baby to its mother through an umbilical cord. Fasting is the cutting of this umbilical cord, in an attempt to achieve an independent personal existence. It might seem that by withdrawing from people in order not to sin, and by not eating in order not to be a slave to the passions, one can almost become just like a monk. Not quite, though.

The ancients understood a lot and sensed even more, though they were not able to express it. Thus they would have understood these notions of withdrawal from the world, of abstinence and silence, and would have praised it all. For example, in Egypt some Stoics once asked certain monks what the difference between them was. Both of these groups were unmarried, poorly clad, and accustomed to fasting. The monks said, “We put our hope in God and abide in His grace”. The Stoics humbly replied, “We do not have that”.

It is possible, in fact, to cut oneself off from people and to cease to have any contact with them, but with a feeling of pride—having spat in their direction, as it were, by way of saying goodbye. However, this kind of ascetic struggle would be demonic. The demon might not openly attack such a hermit, but will converse with him imperceptibly and stealthily plant “intimate” thoughts in his mind.

Withdrawing from the world has to be for God’s sake and for the sake of the people whom the ascetic in question is leaving behind outwardly but with whom he is even more united in prayer. For prayer is essential. Abstaining from food, voluntary seclusion—these things are merely an aid to prayer. If there is no prayer, there is nothing. And so there is no need to run off anywhere or to fast, since all this will be useless. On the other hand, if there is prayer, albeit in an embryonic state, then everything else will follow.

Prayer will engender freedom. I dare say that he who has never prayed has never been free. Is the freedom to move from place to place true freedom if, as we do so, we commit the same sins and suffer from the same problems of a guilty conscience? Is the freedom to indulge in material consumption genuine freedom if, spoilt for choice, we still burn with desire, and since the joys of acquisition will inevitably pass quickly, as with children?

We become free from the shackles of a thousand conventions only on the day when we say goodbye to them. I only become truly free in my communication with my boss once my resignation letter has been signed and delivered. Only then—if, of course, I want to—can I give expression to all that has been on my mind but that I dared not mention before.

A certain character in Nabokov’s fiction decided to shoot himself. While he was walking down the street thinking his daring plan through, a strange thought occurred to him. He realised that he was free and that he could do whatever he wanted. No one and nothing could lay down the law for him, as he had already decided to put a radical end to his connection with this world.

He who loves only this world will be its slave. One has to love another world in order to feel free in this one. Otherwise, all this talk about freedom is, forgive me, foolishness and nonsense and slavish self-justification. “Haven’t you seen / A dog licking the hand that it’s being thrashed by?”2

A certain ancient philosopher was reproached for not showing an interest in the politics and affairs of his fatherland. “On the contrary,” he would say, pointing to the sky, “I am very interested!” Nowadays, it is difficult to find a Christian priest who would answer in the same way. And, as a matter of fact, that philosopher was an ancient Greek, a pagan...

Diogenes—another ancient Greek philosopher—went around the market place with a lantern in broad daylight, holding it up to people’s faces and saying that he was looking for an honest man, a true human being. By this, he wanted to let his hearers know that they were, at best, beings who were similar to humans. He insulted those who saw and heard him considerably. In fact, he called them dumb asses or cockroaches. He could get away with this, in the first place, because the stupid ones would not understand, and secondly because it was impossible for him to be punished, since he had already punished himself. For example, he walked around naked, lived in a barrel and was always hungry. He was totally free from what people might think or say and so could tell them the incriminating truth.

Later, fools-for-Christ acted in a similar way. They were tolerated out of necessity. Had they had any social standing, they would have been torn to pieces. For an Orthodox kingdom can also resemble a prison if no one tells its sovereign the truth. An Orthodox kingdom needs deserts populated by fearless monks and fools-for-Christ walking the streets of its cities. These two categories of holy people are the least vulnerable to attacks from the ruling power. Everyone else, even the patriarch, can be brought down, deposed, strangled, persecuted and defamed. St John Chrysostom, for example—in spite of his hierarchal rank, people’s love for him, and his genuine righteousness—was humiliated and banished.

St John Chrysostom, too, said that he rarely came across real people, but more frequently observed beings who were similar to humans but who nevertheless were as stubborn as asses, lustful as stallions, cunning as foxes, and poisonous as snakes. Nor was he forgiven for saying this. There was much at stake for him. They could strip him of his garments, proclaim him a heretic, convoke a council against him, or defame his name. He died in exile, like a ship cast by the waves onto a desert shore far from his homeland.

Anyone who occupies an elevated position is vulnerable on all sides and open to any storm. One feels sorry in advance for such people, since their ascension to the top resembles the climbing of the scaffold for a public execution. Yet only such people as them will be capable of repeating the words addressed by St Basil to the Arian prefect Modestus: “I am weak, and therefore, only the first blow will hurt. I do not fear exile, for the whole earth belongs to God. I have no possessions. I do not fear death, for it will re-unite me with God”.

It seems that one has to die even before death, in order to meet one’s eventual death courageously. Plato said as much. According to him, philosophy teaches one not so much how to live, but rather how to die. Whichever way one looks at it, those ancient people understood a lot. It was not without reason that the Holy Fathers of the Church cultivated their mind and heart with the plough of philosophy before they sowed the seeds of the Gospel. Whilst in Athens, Basil the Great and Gregory the Theologian not only visited churches but philosophical colleges as well. As St Basil said later, they were like bees going from flower to flower, alighting on certain ones but not carrying everything away from them. For though they were thirsty for knowledge, they were selective as well. Nevertheless, had their minds not been refined by everything they had managed to enrich them with, they might have become zealots and ascetics but never universal teachers.

If one concentrates on studying to the exclusion of everything else then—God forbid!—one risks an encounter with Mephistopheles, like Doctor Faustus. The head will be full of knowledge but the soul will be restless, and in that case such a meeting is quite possible. Instead, one should open the windows of one’s study and listen to the Easter bells. One should also leave the house at least once a week in order to attend the Divine Liturgy. Then the life of the heart will balance the life of the mind and one will not be in danger of going to extremes.

All aspects of spiritual life should be tried and tested by the soul, but in moderation. One should sometimes flee from people but one should, in time, return to them. One should pray after abstaining from food and water, and one should subsequently eat and drink again having experienced the humbling awareness that one can neither pray nor fast properly. One should acquire one’s own inner experience and then check it against the writings of holy people. Sometimes, one should read nothing except the Psalter and the Gospels. And sometimes one should read or re-read a good book, and this should give the soul peace and food for thought.

The ancients are not really “ancient”. They are our contemporaries, our companions even. Across the centuries, there are the same problems that have to be solved by a people made of one blood, who now inhabit the entire face of the earth. Their whole task is to “seek God, in the hope that they might reach out for Him and find Him, [for] He is not far from each one of us” (Acts 17. 26–27).

Translated from the Russian for OrthoChristian.com