Introduction by Matfey Shaheen:

Glory to Jesus Christ! Glory Forever! Here, we present yet another article on the history of Orthodox Carpathian Rus’, and the Carpatho-Rusyn or Transcarpathian Ruthenian people, who hail from mountains of Western Ukraine, Eastern Slovakia, Southern Poland, and the nearby lands.

The Rusyns belong to a unique and ancient land, shrouded in beauty and mystery, which was visited and evangelized by Saints Cyril and Methodius in the first millennium. Though they are a very small and largely unknown nation, Carpatho-Rusins have made mountainous achievements for Holy Orthodoxy, and Ruthenians are among some of the most important figures in the history of the Russian Church, both in the homeland and in diaspora. As a matter of fact, they founded literally hundreds of churches in North America. It was the Rusyn Saint Alexis Toth who triggered a mass conversion which essentially formed the majority of what became the OCA, their own website claiming: “Any future growth or success may truly be regarded as the result of Father Toth’s apostolic labors.”1

This article serves as an introduction to the history of the Church in Transcarpathia. It has been edited and contextualized to illustrate this history for those unfamiliar with this remarkable land and people. Please see the provided links and footnotes for more information. Also see the compilation of articles on Saints of Carpatho-Russia on our website.

According to archaeological and written sources, Christianity came to the territory of modern Transcarpathia before it was officially incorporated into Kievan Rus’. Most experts, including Joannicio Basilovits,2 Michaelem Lutskay,3 Archimandrite Vasily (Pronin)4, and others) link the spread of Greek-Rite Christianity to the region with the Equal-to-the-Apostles Saints Cyril and Methodius, or at the very least, with their students.

Some Hungarian sources note that when the Ugrians came into the Pannonian-Carpathian Basin (and the region of Pannonia which became known as the Hungarian Plain), the (Carpathian) Slavic population had already established an Episcopate (see: The Tale of the Migration of the Hungarians5).

In the opinion of Archimandrite Vasily (Pronin), the disciples of Saints Cyril and Methodius (and St. Procopius of Sázava), (or in some stories, the Saints themselves)6 having been forced to leave Sázava Monastery and the Bohemian (Czech) Lands, laid the foundation of Holy Dormition Uhlia Monastery78 in the Tiachiv region of Transcarpathia, near the Romanian border.

Evidence for the fact that the Greek Rite was spread throughout Transcarpathia is the activity of Saints Georgy, Ephraim and Moses “the Hungarians” (meaning Carpatho-Rusin)9 at the court of the Kievan princes Saints Boris and Gleb.

In those days, monasteries were places where spirituality and education flourished. Analyzing the sources and monographic material, we can conclude that prior to the Tatar-Mongol invasion, monasteries in Transcarpathia likely existed not only around Uhlia, but also in Hrushevo. This idea is confirmed by early twentieth-century researcher Jurii Zhatkovych. He writes that after the departure of the Tatars, the Hrushevo monks complained to the Hungarian King Béla IV about the loss of documents and letters of land ownership.10 As for the monastery in Mukachevo, documents concerning its foundation have not been found earlier than 1360.

The blooming of Orthodoxy in Transcarpathia is associated with the acts of the Prince of Podolia (near Volhynia) of the Gediminid dynasty Fyodor Koriatovych. The Prince rebuilt the Mukachevo monastery and transferred to it several villages from his estate; he also contributed to the development of education and culture in the region.

A difficult question remains in the definition of the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the region. Historians recognize that two centers of ecclesiastical authority were developed in Transcarpathia—the first in Mukachevo, and the other in Hrushevo. In the midst of the fifteenth century, in Mukachevo, there was mention of one Presbyter Luke, who could carry out episcopal functions and was subordinated to the Serbian Metropolitan. A letter from Patriarch Anthony of Constantinople in 1391 on the provision of the status of Stavropegia to the Hrushevo Monastery is also known to us. In 1491, there is mention of one Bishop John in Mukachevo, who sought to extend his influence throughout the territory of Transcarpathia.

During the period of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Orthodox Church in Transcarpathia began to experience strong pressure from Catholicism and the Reformation, [and by extension, the Counter-Reformation of the Jesuits, the Union of Brest 1595-96, and the religious conflicts across Europe—Trans.] On the initiative of local rulers and the church elite, the 1646 Union of Uzhhorod (The Union of Ungvár) was conducted. According to the Unia, the “new church” would preserve the eastern rite and the language of worship, but recognize the Pope and his authority. After the death of Bishop Vasily (Tarasovich), Peter Parthenius was elected as the Uniate bishop, and Ioanniky (Zeykan) was elected as the Orthodox Bishop. The latter was forced in 1663 to leave the Mukachevo Monastery and lead the diocese from Imstichovo and Uhlia (Ugolka). From that time on, the Orthodox faith underwent hard times of persecution. The lands of Maramuresh11 (the eastern part of Transcarpathia, along the Ukrainian-Romanian border) remained the center of resistance to the Unia and Latinization, where about ten monasteries were founded at the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth centuries. Among them, according to the “Account of the Monasteries of Máramaros”12, there were Dragov, Krychev, Boronev, Bedevlyansky, Bielotserkva (White Church), Vilkhivsky, and Bichkovsky monasteries. All of them were founded by the efforts of the Orthodox Bishops Joseph (Stoika; 1690-1711) and Dosifey (Fedorovich; 1717-1735), who sought to create a strong fortress for the defense of Orthodoxy in Transcarpathia.

The Austrian authorities sided with the Uniate church, and did everything to prevent the election of new Orthodox Bishops, and the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa13 declared that the Orthodox Church had been annihilated in Transcarpathia. The Eastern Rite and the Orthodox faith were preserved thanks to the devotion of the local Carpathian peoples to the faith of their ancestors, and the activities of individual Uniate priests.

The famous dissident against the Latinization was the polemic writer Mikhail Andrella Orosvigovskyj (1635-1710). He openly denied the Union and wrote several polemical works; the most famous of them are “The Logos”14 and “The Defense”15. Fleeing persecution, he moved to Iza, where he died. His work was continued by Father Ioann Rakovsky (1815–1885), who had a significant influence on the revival of Orthodoxy.

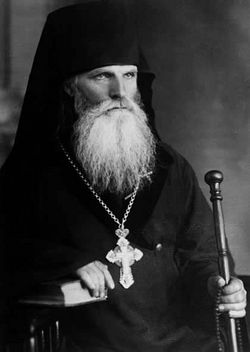

Saint Alexis the Carpatho-Rusyn (Kabalyuk) With the beginning of the twentieth century, the revival of the Orthodox Church in Transcarpathia began. The Austro-Hungarian authorities tried in every possible way to prevent this, believing that the movement for the revival of Orthodoxy was of a social and national liberation character. The authorities organized two trials against the Orthodox in Maramorosh-Sighet16, in 1903–1904 and 1913–1914, but these prosecutions could not stop the revival of Orthodoxy. Saint Alexis the Carpatho-Rusyn (Kabalyuk; † 1947)17 stood at the head of the Orthodox movement in Transcarpathia.

Saint Alexis the Carpatho-Rusyn (Kabalyuk) With the beginning of the twentieth century, the revival of the Orthodox Church in Transcarpathia began. The Austro-Hungarian authorities tried in every possible way to prevent this, believing that the movement for the revival of Orthodoxy was of a social and national liberation character. The authorities organized two trials against the Orthodox in Maramorosh-Sighet16, in 1903–1904 and 1913–1914, but these prosecutions could not stop the revival of Orthodoxy. Saint Alexis the Carpatho-Rusyn (Kabalyuk; † 1947)17 stood at the head of the Orthodox movement in Transcarpathia.

After the entry of Transcarpathia into Czechoslovakia in 1919, under the name Subcarpathian Rus' (Podkarpatská Rus), the Orthodox Church finally received the opportunity to develop freely. According to Canon Law, the Serbian Orthodox Church received Transcarpathia into its territory as part of its canonical jurisdiction. In 1921, the Serbian Holy Synod sent its hierarch, the Bishop of Niš, St. Dosifei (Vasić), to Subcarpathian Rus’. This Holy Hierarch has a significant role in the establishment of Orthodoxy among the Rusyns. He founded dozens of Orthodox parishes and streamlined monastic life; monasteries for men and women were established in Iza, Lipcha, and Tereblia.

St. Dosifei (Vasić) One of the most significant problems of the time was the lack of Orthodox clergy. In this regard, in 1920-1930 many Transcarpathians received spiritual education in theological institutions of Serbia. After Bishop Dosifey, the Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Church was led by the bishops: Irinej Ćirić of Novi Sad, Seraphim (Ivanović) of Prizren, and Joseph (Cviević) of Bitola.

St. Dosifei (Vasić) One of the most significant problems of the time was the lack of Orthodox clergy. In this regard, in 1920-1930 many Transcarpathians received spiritual education in theological institutions of Serbia. After Bishop Dosifey, the Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Church was led by the bishops: Irinej Ćirić of Novi Sad, Seraphim (Ivanović) of Prizren, and Joseph (Cviević) of Bitola.

In 1931, the ancient Cathedra of Mukachevo was restored, which also included within its canonical-jurisdictional territory the parishes of Eastern Slovakia (The Diocese of Prešov). The first Bishop of Mukachevo and Prešov was Damaskin (Grdanički). The Hierarch reorganized the spiritual consistory, and helped to elevate the education of the clergy. To do this, he organized pastoral and theological courses at St. Nicholas Monastery in Iza. The diocesan home was also built in Mukachevo. The Czechoslovakian government began to provide financial assistance to the Orthodox clergy.

In 1936, the Diocese of Mukachevo and Prešov included 127 parishes and 160 thousand parishioners. There were also five monasteries: three male ones: St. Nicholas in Iza, Holy Transfiguration in Tereblia, the Skete of the Venerable Job of Pochaev in Ladomirová —[That monastery was deeply connected to Holy Trinity Jordanville Monastery and the ROCOR. First Hierarch Metropolitan Laurus (Škurla), who reunited the Russian Orthodox Church, was born and began his monastic life in that village, and the brotherhood later moved to New York and joined the monastery at Jordanville, bringing the printing press with them, which still functions to this day. Their famous Russian language publication Orthodox Rus’ was originally called Orthodox Carpathian Rus’ (Православная Карпатская Русь), and is still in print today, and available in electronic form—O.C.]

The Monastery of St. Job in Ladomirová in Slovakia by Archimandrite Cyprian (Pyzhov), Jordanville, New York. ROCOR Studies.org

The Monastery of St. Job in Ladomirová in Slovakia by Archimandrite Cyprian (Pyzhov), Jordanville, New York. ROCOR Studies.org

In Transcarpathia, during the Czechoslovakian period, two women’s monasteries were also founded, the Nativity of the Holy Theotokos Mary (in Lipcha) and Holy Annunciation (in Domboky). In addition, there were five more male sketes.18

In the 1920s and 1930s, some of the Orthodox parishes, monasteries and sketes were also subordinated to the Archbishop of Prague Savvatij (Vrabec), who was consecrated by the Patriarch of Constantinople Meletius (Metaxakis).

In 1938, Bishop Vladimir (Rajić) was appointed to the throne of Mukachevo and Prešov. The bishop did not stay in Mukachevo for long, because, according to the Munich Betrayal [conducted on September 30, 1938, between the allies and the Nazis, allowing for the occupation of Czechoslovakia—Trans.], part of Subcarpathian Rus’ was occupied by Hungary. The diocesan administration and the Bishop moved to Khust, which, in March 1939 was also occupied by the Hungarians. In April of 1941, Bishop Vladimir was arrested, and in October of that year, he was sent to Serbia.

The Hungarian regent Miklós Horthy de Nagybánya appointed Mikhail Popov as “administrator of the Greek-Eastern Hungarian and Greek-Eastern Ruthenian ecclesiastical church entities”. Popov pursued a Hungarian policy and tried to create an “autocephalous Orthodox church” in Hungary.

On February 5, 1944, Hegumen Theophan (Sabov) was appointed the new administrator. In the document, his position was listed as “the Episcopal Deputy and Administrator of the Orthodox Diocese of Mukachevo and Prešov.”

Bishop Damaskin In October 1945, the Diocese of Mukachevo and Prešov came under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. During the Soviet era, the Orthodox Church in Transcarpathia (as well as in other places) experienced many tragedies and persecutions. Almost all monasteries and sketes were liquidated, some priests were repressed.

Bishop Damaskin In October 1945, the Diocese of Mukachevo and Prešov came under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. During the Soviet era, the Orthodox Church in Transcarpathia (as well as in other places) experienced many tragedies and persecutions. Almost all monasteries and sketes were liquidated, some priests were repressed.

A qualitatively new stage in the life of the Orthodox Church began in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the Mukachevo-Uzhhorod diocese was ruled by Archbishop Evfimiy (Shutak). For several years, dozens of Orthodox churches and monasteries were renewed, and spiritual education was revived in the region. In 1994, the Khust-Vinogradov diocese was detached from the Mukachevo-Uzhhorod diocese.

In 2000-2007, the diocese of Mukachevo was led by Bishop Agapit (Bevcik). In December 2007, the Holy Synod of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church appointed Fyodor (Mamasuev) as Bishop of Mukachevo and Uzhhorod, who in 2018 was raised to the dignity of Metropolitan by His Beatitude, Metropolitan Onuphry of Kiev and all Ukraine.19 The Khust diocese is governed by Metropolitan Mark (Petrovtsy).

At the end of 2008, there were about 520 parishes and 35 monasteries in the territory of the two dioceses of Transcarpathia.

The periodicals “The Orthodox Chronicle” (Mukachevo) and the “Spiritual Well of the Carpathians” (Khust) are published.

Update: As of 2020, according to current statistics, that number has grown to approximately 5372021 parishes and 422223 monasteries and sketes. This illustrates that the Transcarpathian dioceses of the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church are flourishing to this day, and have even strengthened despite the schism in Ukraine, and death threats against Transcarpathian clergy by schismatics. Glory to Jesus Christ! Glory Forever—Trans.