The name of Alexander Chashkin is known to everybody who has at least some familiarity with church art. He has worked on the beautification of many churches, including the Iveron Chapel in Red Square and the Church of St. George the Victorious on Poklonnaya Hill in Moscow, the Monastery of St. John the Theologian in Poshchupovo in the Ryazan region, the Svyatogorsk (“Holy Mountain’s”) Lavra in Ukraine, to name just a few…

In his interview with Pravoslavie.ru Alexander has talked about painter’s responsibility, on why even mediocre icons can exude myrrh and what upsets him in contemporary church art.

—You began to paint icons when you were thirty-five. Please tell us how it came to pass.

—At first I didn’t think of painting icons. I had several different professions. For example, at one time I worked at a hippodrome training race horses, and in the evening I would attend classes at the Moscow Surikov Art Institute (the Department of Additional Education) where I painted landscapes. Then I continued my training at the Opera Studio of the Central House of Workers of Arts in Moscow, though I was over thirty and couldn’t dream of an opera singing career. And, since I was beginning my life in the Church, I joined the choir of All Saints’ Church at Sokol (Moscow) where I sang for five years.

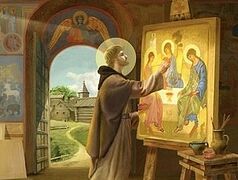

A nun from that church introduced me to a famous spiritual elder. He asked me, “What do you do?” I replied, “I paint landscapes and sing in the choir.” Then he addressed the nun, “Vera, lead him to Fr. Zenon [Archimandrite Zenon (Teodor; b. 1953)—a leading contemporary Russian iconographer, expert in art and teacher of icon painting.—Trans.]—he will paint icons. And don’t listen to him when he says that he won’t.” Thus we went to St. Daniel’s Monastery, to Fr. Zenon. From that day a new life began for me: once I saw Fr. Zenon painting icons, I realized that a true master was in front of me. “May I assist you?” I asked. The next day I began to help him by rubbing up paints. It wouldn’t have occurred to me to say that I wanted to paint icons. I just helped him by rubbing up paints and observed Fr. Zenon paint. That was the best possible school!

—Who taught you to understand the essence of icons, not only through the sphere of art, but also from a theological perspective? Was it Fr. Zenon?

—Yes, I took an interest in theology of icons as well. On Fr. Zenon’s advice, I started with reading “Iconostasis”, a theological work by Fr. Pavel Florensky. By the way, to express my gratitude to Fr. Pavel Florensky for all he had done for our Church I had his image installed at St. Nicholas Cathedral in Washington, D.C., though without a halo in obedience to the Church canons as Fr. Paul wasn’t recognized as a saint.

—Were you baptized as an infant?

—I was baptized as an adult when I was about thirty. As was the case with most of my peers, I wasn’t satisfied with materialism because it didn’t provide answers to many questions and couldn’t explain the nature of our world thoroughly. People were trying to find answers to spiritual questions, but sometimes in a wrong direction—some were carried away by Indian philosophy; they couldn’t find the truth in it either. We are much indebted to Russian classical literature, which set us in a right direction. I converted to the faith mostly thanks to Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Tolstoy was the first. As I read his books I saw that he sincerely believed in God, though he seemed to be lacking in something important (incidentally, my first monumental work was frescos at St. Nicholas Church at the Tolstoy family’s Yasnaya Polyana Estate near Tula).

Next I discovered Dostoevsky, and after him I began to read about Orthodoxy consciously. Thus, little by little I came to understand that I should get baptized. Exactly a year later I joined a church choir, and five years later I became a pupil of Fr. Zenon. Interestingly, I didn’t tell him that I was a painter and it was not until a year later that I first showed him my icon. He told me, “Yes, this is your mission. You can paint icons.”

—Who else taught you to understand icons?

—Tamara Yakovlevna Volkova, a pupil of Nun Yuliania (Sokolova) [1899—1981; a prominent Russian icon painter and restorer.—Trans.], with whom we worked at “Sofrino” [the official factory of the Russian Orthodox Church, located in the Sofrino village in the Pushkino district near Moscow.—Trans.). Thanks to Tamara Yakovlevna I felt the continuity of the living tradition.

—Icons are called “windows to Heaven.” Can every icon become such a window?

—It’s a very difficult question. For instance, recently I got a call from the German city of Trier, St. Constantine the Great’s birthplace, where I made frescos for the Church of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste and where I still work with an assistant on its beautification. Six months ago I painted an icon of St. Joseph the Hesychast for this church. So the people who called me said that this icon started streaming myrrh! This phenomenon certainly has nothing to do with me or my skills.

What am I driving at? Every icon is an enigma, a mystery that we will never be able to solve. In some cases even paper reproductions of icons give myrrh. And I was told a story about a graveyard caretaker who began to paint icons; though they were mediocre, to put it mildly, they too streamed myrrh.

Such great masterpieces as the Vladimir icon of the Theotokos or “The Holy Trinity” by St. Andrei Rublev never stream myrrh. Why? Maybe because they by themselves represent an image of the celestial world by the power of their craftsmanship and spirit? We can only speculate.

—But an icon-painter should be responsible for his work, right?

—Absolutely. What we have just talked about isn’t anyone’s area of responsibility. He should do his work seriously and consciously, especially when it comes to painting icons; that is his duty and responsibility—something he will have to answer for.

If a painter who has little to do with the Church decides to paint an icon, the result will be just a painted iconographic scheme and not an icon. People will pray in front of it, but how will the author who has done his work without due reverence answer for this?

In my view, this is the main responsibility of icon-painter: whether he begins to paint an icon with faith in his heart or he is only motivated by profit. One of the most widespread sins of our age is consumerism, and it easily leads to apostasy. Alas, there is even a consumer attitude towards the Church…

—How can we oppose it in the church life?

—Through the regeneration of communities. They are instrumental in combating a consumer attitude towards the Church. In a community we are not “walk-ins” who only come to church to “satisfy” their “spiritual needs”—we are members of one family and for us the Liturgy is our common work. And community helps us understand that we, all the faithful, make One Church and the Body of Christ.

—If a religious person who creates icons of saints realizes that he is lacking skills of a professional (the composition is poorly planned and executed, the anatomical features are inaccurately represented, etc.), isn’t it about responsibility, too?

—Yes, it’s about responsibility. Someone who paints icons must strive to learn and improve his skills. Unfortunately, what you’ve just described is a common phenomenon. Once Fr. Zenon said that the sole problem of contemporary iconographers is the absence of basic drawing techniques. If someone believes that he will create a real masterpiece only by Divine inspiration and through prayer, without studying, without devoting a lot of time to learning, he won’t succeed. Without learning, mastering skills and praying on a permanent basis there will be no result.

—For more than ten years you taught at the Russian Orthodox University of St. John the Theologian and were Dean of the Department for Church and History Painting. In your opinion, what are the essential components of teaching iconography to students?

—Incidentally, I agreed to teach there because I had recalled the composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who said when he was invited to the Conservatory: “All right, by teaching others I will probably learn something myself.” So, when I began to teach students, I tried to explain how important it is to draw well, to sense the graceful movement of lines… I would repeat what I had heard from Fr. Zenon: “At the moment a painter, not least an icon painter, feels that he has become a master, he ceases to be a painter. A true artist feels he is still a pupil his entire life and strives to learn.”

An icon-painter must keep perfecting his skills and improving his knowledge of theology. In order to paint an icon independently you need to copy numerous outline drawings. And working only with outline drawings your whole life means making no progress.

—So you are still learning?

—Definitely! I worked at the Serbian Dajbabe Monastery in Podgorica, Montenegro. When I arrived there about five years ago, I intended to use silicate paints—a traditional material of our time. But Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral (a conversation with this man is already a blessing) said to me in Russian: “No, Alexander, we only need frescos.” So I had to learn fresco—a technique of painting on wet plaster; it is rather complicated as you have to do everything fast and without mistakes [you paint while the plaster is wet, and then you won’t be able to correct mistakes by overpainting.—Trans.].

A chapel dedicated to the centenary of the martyrdom of the Royal Passion-Bearers was built at that monastery. Three months ago Fr. Daniel (Ishmatov), its abbot, invited me to paint frescos for that chapel. I painted the images of Emperor Constantine (who made Christianity the state religion); King Stefan I of Serbia; and St. Nicholas II. Emperor Nicholas is depicted with a cross in his hands, while a scepter and an orb are held in the hands of the Theotokos. The main idea was the end of Orthodox monarchies on the earth. Having seen my frescos, Metropolitan Amfilohije awarded me with the Order of St. Nicholas II, instituted by the Metropolitanate of Montenegro.

“I left, fully understanding what holiness is like”

—You created some frescos for St. Nicholas Cathedral in Washington, D.C., the principal cathedral of the OCA. You also knew Bishop Basil (Rodzianko). Can you share some memories of him?

—He was a very remarkable person, absolutely open and approachable. Despite his age and experience, he had the ability to see the world through a child’s eyes. I felt his fatherly care all the time. I have a high opinion of his work, The Big Bang Theory and the Faith of the Holy Fathers—a book that still remains largely underappreciated. Bishop Basil was a humble man, and his pension of $400 was sufficient only to pay for gasoline.

—What did you as an iconographer gain from meeting such people as Bishop Basil, Archpriest Dimitry Grigoriev (1919—2007), Dean of St. Nicholas Cathedral in Washington, and others?

—Those meetings showed me genuine Christianity and Christian love, allowing me to see the gleam of the transforming light of Tabor that we try to communicate in our icons.

It was a blessing for me to meet such people, each of whom in his own way was an example of holiness. I remember my first meeting with Fr. Kirill (Pavlov). On that day I was at the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra with my acquaintances and didn’t want to go to confession, so I decided to leave quietly. Fr. Kirill noticed that and called me. I came up to him and we spoke for about fifteen minutes. I left, fully understanding what holiness is. Fr. Kirill showed it to me—genuine Christian love. In those fifteen minutes I sensed how much love Fr. Kirill had, and he gave this love to everybody no matter how long they talked—for a few minutes or for three hours.

My recent meeting with Fr. Fyodor Konyukhov is remarkable and important to me too. He revealed to me that his exploits as a traveler, his round-the-world voyages on an ordinary rowboat, even in massive storms, became possible only with faith and prayer.

—You always remember Patriarch Alexei II with warm feeling and gratitude. Can you share a story associated with him that brings back the fondest memories?

—I was making frescos for the altar of the Church of St. Sergius of Radonezh at Vysokopetrovsky Monastery in Moscow. One day, while I was working, some people who looked like bandits entered the church. That story happened in the “crazy nineties.”

“What are you doing here?” they addressed me. “I’m painting,” I shrugged my shoulders. “Get out! Or we’ll kill you! Aren’t you scared? Are you so brave?” the mobsters said, confirming my first impression of them. It happened so fast that I didn’t really have time to be scared and to realize that I was in danger. “If you kill me, I will surely go to heaven,” I replied. “To be brief, if we find you working here tomorrow, we’ll make short work of you. Tomorrow at one in the afternoon we’ll come and kill you,” the thugs concluded.

Right away I told this to Archimandrite John (Ekonomtsev), who was then abbot of Vysokopetrovsky Monastery, and Fr. John informed His Holiness Patriarch Alexei, his friend, that some individuals were going to come and kill Chaskin. The next afternoon His Holiness, along with his entourage, arrived at the monastery by one o’clock to save me! Though officially he explained his visit this way: “Let me see what you’re painting here.” The Patriarch was pleased with everything he saw in the church, but, most importantly, the way he displayed his concern moved me the most. As for those bandits, their car appeared again, slowed down, and then drove away. Nobody was going to kill me anymore.

The most “difficult” icons

—I wonder if you have ever worked on icons that you found especially difficult to create?

—Curiously enough, I always find it very hard to paint icons of one of my favorite saints—St. Seraphim of Sarov. Every time I finish an icon of this saint, I’m not satisfied with the result. When his relics were discovered for the second time in 1991, a competition was announced with the view of creating the best icon of this saint, which would accompany the procession to Diveyevo. And I became the winner. Though it was a great honor, I still wasn’t completely satisfied with my work: it seemed something was missing there to represent the saint’s exceptionally high level of spirituality. And how can we, ordinary human beings, comprehend the holiness of saints?

And the same thing happens every time… In the 1966 dramatic film, “Andrei Rublev”, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, there is an episode when a bell is cast. While everybody is rejoicing, the boy who cast the bell is weeping. He says, “My papa never told me the bell-casting secret! I don’t like it!” Can we really assert that “I’ve created a good icon of the Savior or of the Mother of God”? I don’t dare to think so.

—What do you do when you don’t know how to paint an icon of a saint whose iconography hasn’t fully developed yet?

—Iconography of the New Martyrs poses the biggest problem to modern icon-painters. Though there are photographs and even films, there is no “perfect” iconography, which must develop for centuries to allow us to represent a saint as a dweller of heaven. So, when it comes to iconography of the New Martyrs, we must try to find a way out ourselves, capturing a physical likeness (as in portraits) and displaying a saint in his transformed state, in Paradise. But this presupposes Herculean efforts and an enormous responsibility.

I look at photographs of a saint (whose icon I’m going to paint), read his Life, his biography, try to conceive his iconographic image, and address him in prayer: “Holy God-pleaser, help me depict you.”

At St. Nicholas Cathedral in Washington, D.C., I covered a whole wall with images of New Martyrs.

—What upsets you in the present state of church art?

—What upsets me is that not everybody sees the difference between a holy icon and a painting with religious themes. An icon shows us the otherworldly, spiritual realm. Realist works depict real-life events and figures, while icons (of saints) depict transformed figures. Fr. Alexander Schmeman rightly defined the iconographic canon as the whole range of techniques that were developed over the centuries to depict transformed reality.

And how strange it is that not all Orthodox people even understand this difference. It is more regrettable that some Orthodox even can’t distinguish the image from the prototype, failing to understand the meaning and role of icons and that, say, standing in front of an icon of the Theotokos, we pray to the Virgin Herself and not to Her image.

It distresses me that uncanonical images of God the Father still appear in our churches. And the argument that icons depict only the Second Person of the Holy Trinity (because Christ came to this earth in the flesh and dwelled among us) and can’t depict God the Father because He is invisible was among the most important ones during the Iconoclastic Controversy… The icon became possible thanks to the incarnation of Christ.

Clearly, with time much of the meaning of icons were forgotten, and new images were painted over ancient ones… But we live in the twenty-first century! As far back as 100 years ago the Russian icon was discovered: the light of genuine iconography and the light of heaven were uncovered from the “darkness” and later records. Maybe it would be wiser to be guided by this light (from a spiritual perspective) and not by plump-cheeked images of the period of “The Most Holy Governing Synod”?1

Among my favorites is St. George’s Church in Staraya Ladoga [a village in Leningrad province.—Trans.], which still preserves some twelfth-century frescos. Why do many rectors want their churches to be covered with frescos in the Academic style? Why adopt the mediocrity and emptiness of the period of the Most Holy Governing Synod now, in the twenty-first century?

—And what gives you hope?

—The fact that there are also competent priests who are able to differentiate true church art from low-quality mass-produced art; who realize the essence and significance of icons; who regard them not as a mere “Bible for the illiterate” or paintings on historical themes, but as complex theological works of art that help us understand Orthodoxy better. Icons are “windows to Heaven”, through which Divine light penetrates into our reality.