A city that is set on an hill cannot be hid (Mt. 5:14). These words of Christ the Savior concern all Christians as a reminder that outsiders will develop an opinion of the Church judging by our lives. But in a narrow sense, addressed to the Apostles, this phrase primarily applies to the clergy, who always attract everybody’s attention, who are always judged and should be ready to answer the disputers of this world (cf. 1 Cor. 1:20) any moment.

The clergy are supposed to isolate themselves from others. Bishops of the past centuries kept parish priests from marrying their sons to peasant girls, fearing that they would inculcate their coarse manners in them, which are alien to the clergy.

Seminary education and everyday ethics would make even a rural priest (a commoner by birth) who tilled the soil together with his parishioners stand out from the masses. So, in addition to the traditional derisive attitude towards the clergy in Russia, there was involuntary respect for them, which is seen in the following saying: “You can recognize a priest a million miles away.”

Even in “the Era of Stagnation” [the era of economic problems in the USSR that began during the rule of Leonid Brezhnev in 1964 and continued under Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko until 1985.—Trans.], which was like a spiritual desert, an experienced eye always recognized a priest in a crowd, though he would wear, like everybody else, usual Soviet mass produced clothes and long hair (which was in fashion among young people). He was like everyone else, but still different!

Until recently, bishops in Russia were a rarity. Even in the mid-eighteenth century there were two dozen dioceses at most. Bishops were surrounded by honor, beyond which it was hard to scrutinize merely human faces. The writer Nikolai Leskov (1831–1895), who knew the clergy very well, would mock the bishops who never walked but only rode in carriages and thus acquired interesting diseases.

Strangely enough, apart from “The Bishop”, the famous short story by Anton Chekhov (1860–1904), which is moving yet extremely ruthless to its main character, Russian classical literature remained strikingly indifferent to the image of the Orthodox bishop. Even Leskov, who colorfully portrayed ordinary clergy in his novel Cathedral Clergy, in his other works only mentioned in passing two Philarets: “the wise” (St. Philaret of Moscow), and “the good” (the Metropolitan of Kiev), leaving only his semi-anecdotal essay, “Trifles from the Lives of Archbishops”, for the rest of Russia’s episcopate. So the bishop’s personality and his spiritual life remained an unwritten page in Russian literature.

Such thoughts arose in my mind (and then their truth was confirmed) when I was planning an ordinary and incognito pilgrimage trip. After six years of archpastoral ministry, which mainly consists of routine work in a newly-established diocese, I wanted to feel like a simple monk (or a hieromonk so that I could celebrate the Liturgy), leaving the honors and vanities (which my first instructor called “Chinese ceremonies”) far behind for a while.

I can say for certain that the words of Alexander Pushkin’s famous verse from the novel, Eugene Onegin, “A restlessness took hold of him, an urge to move away”, weren’t about me. There was no anxiety, no desire to run away from myself. On the contrary, I wanted to be myself for a while, and traveling was the finest opportunity in my case. So, if there were any verses in my mind at the beginning of my journey, it was a simple song by the poet Bulat Okudzhava (1924–1997): ”O brother, let us bow out, O brother, let us soar up...”

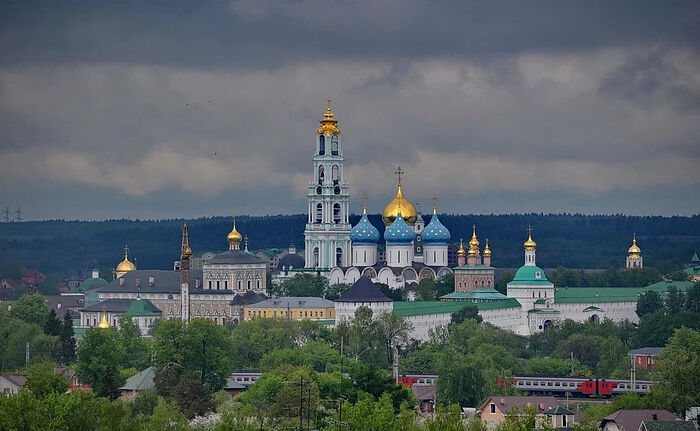

The Lavra

Together with several companions we left for the Holy Trinity–St. Sergius Lavra. I wanted to be there, in the place where I received the first lessons of monastic humility. Here, near the relics of St. Sergius, I had studied at the Theological Academy and had been privileged to be close to Archbishop Alexander (Timofeyev; 1941–2003), who served as its rector for many years.

At last we arrived to the holy Lavra’s gate. There were almost no pilgrims there and you couldn’t hear the noise of garrulous crowds of tourists speaking in diverse languages. The pandemic has temporarily stopped the stream of curious idlers and gapers, who were ready to make the following flippant remark any moment: “I’ve prayed at St. Sergius’ too!”

In these months, the Lavra like nobody else has “tasted” the horrors of this cunning illness. Dozens of Lavra fathers have died of this virus; and none of them complained or expressed any signs of discontent with the “injustice” of Divine providence. Put on drips and connected to ALV apparatuses in the hospital wards, laconic Lavra monks would repeat the words of the Apostle Paul: For to me to live is Christ, and to die is gain (Phil. 1:21).

Fr. Pavel Florensky called the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra the spiritual heart of Russia. If the Lavra is the heart, then the Trinity Cathedral is the heart of the heart, the center of the nation’s spirituality, faith and prayer for all the faithful in the Russian land.

Our first service at the monastery was here. At dawn in front of St. Sergius’ relics the brethren conduct the joint prayer service to ask for the saint’s blessing for the coming day—work and obediences in honor of the Most Holy Trinity. At this time of the day only the monastery brethren and a handful of pilgrims gather here.

Immediately after the prayer service the midnight service is celebrated and the Divine Liturgy begins. The Holy Trinity Church is the oldest in the Lavra. It was built by St. Sergius’ disciple and successor—St. Nikon of Radonezh. St. Andrei Rublev painted his famous “Holy Trinity” icon for the iconostasis of this church “to praise” St. Sergius. Numerous later layers were removed from it in the early twentieth century, and now the icon is kept at the museum. Today what you see in the iconostasis of the Holy Trinity Church is copy of it. This iconostasis consists of tiers of icons placed on wooden horizontal transoms, which have no decorative carvings. Its interior is austere, but not really ascetic. Old silver candlestands darkened with age and huge icon lamps indicate that in ancient times, Russian people were ready to give their last penny for the adornment of churches.

Looking at these precious items, I begin to understand St. Philaret of Moscow, who said that nothing should be artificial in church—only natural gold and natural silver. I recall our sad church reality: cardboard iconostases, gold-colored foil, cheap imitation of gilding. Were people in the fifteenth century really richer than us?

I took the place of the monk who had celebrated services of intercession and sung the Akathist hymn at the shrine before me. Behind me there was the entrance to St. Nikon’s side-altar and St. Serapion’s Chamber that houses countless relics, notably particles of the True Cross. But I thought about them briefly. The grace that flows from St. Sergius’ relics prevails over everything else. I felt as if he was present, hearing everything and praying with us…

Though not all the restrictions had been lifted yet, the stream of pilgrims continued unabated. The choir organized itself right away—two sopranos and a tenor were singing harmoniously and with reverence. There were heaps of intercession lists, which by themselves could become material for a very interesting sociological research. There was an intercession list written by the unsteady hand of an old person—someone wanted to remember everybody and covered the whole paper with the names to be prayed for, leaving no blank space, and one name was written across it. There was also a child’s intercession list, with an explanation after each name: “mom”, “dad”, “brother”… Lastly, there was an “advanced” list, which had been printed out—it was more convenient to read but its author’s soul was absolutely invisible…

Every minute my attention was distracted by people’s blessing requests: “Father, bless! Oh Vladyka, I’m sorry!”, “Please, bless me for a medical treatment (for my studies, to serve in the army)!” “Pray for Russia (for Ukraine, an easier life)!”

After the Dismissal of the prayer service I wanted to start again because the influx of believers wasn’t going to stop… I couldn’t help but recall the following lines by the poet Marina Tsvetaeva (1892—1941):

Moscow! Such an enormous

Refuge for wanderers!

In Russia everyone is homeless.

And all of us will come to you…

For all our penal brandings,

For every disease—

The infant Panteleimon

We have, the one who heals.

The unity with people filled my soul with an immense sense of peace. As long as there is prayer, the Russian land will live, problems will be solved and things will be set aright! But I wasn’t alone—I had promised to show the monastery to my traveling companions. Having celebrated continuous prayer services for some time, I finally stepped down and let an elderly monk continue. Then we went outside into the main square of the Lavra.

The Lavra’s true wonder is the amazing harmony of its buildings that were created in different centuries. The austere fifteenth-century architectural forms go well together with a palette of Moscow Baroque colorful ornamented tiles of St. Sergius Church and the Chapel-over-the-Well. The “provocative” splendor of the bell-tower, built in the second half of the eighteenth century in the style of European Baroque, doesn’t clash with the austere “Russian” aspect of the Dormition Cathedral and has something in common with the elegant Church of the Holy Spirit.

And next we proceeded to the Moscow Theological Academy, to the royal chambers, constructed in the late seventeenth century for travelling Russian monarchs. I couldn’t help but recall Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, who would visit the Holy Trinity Monastery twice a year for the feasts of St. Sergius. The Tsar would always travel the final part of the journey (several miles long) by foot; his pilgrimages, which could last weeks, gave great joy both to courtiers and common folk who loved to watch the monarch go fishing and treat his entourage to his thin fish soup when he stopped to rest for a while.

For me the Moscow Theological Academy is my alma mater, my nourishing mother, the school of high church scholarship where I studied in the first years of the new millennium. Our souls were filled with such high hopes! How we desired to labor for the Church, for the faithful, and for our country!

The famous Lavra Museum of Church Archeology was the most inaccessible museum of the Soviet era. Under the Bolsheviks, the Kazan Cathedral In St. Petersburg housed the Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism. And this Academy has a true treasury of church antiquities: a vast collection of icons, copper works of art and liturgical vessels. The objects associated with the lives of two outstanding hierarchs—Metropolitan Nikolai (Yarushevich) and Patriarch Alexei I who contributed to its revival—are full of life.

Museums are fine, but real life is closer to my heart. The next day I celebrated the Liturgy in the Holy Trinity Church. It really felt as if I had received a gift I didn’t deserve. It was one of the best Liturgies in my life—an ordinary Liturgy with two priests and a deacon. There were no fidgeting subdeacons, no eagle rugs, no Byzantine pomp. An ordinary Liturgy—what can be loftier and purer!

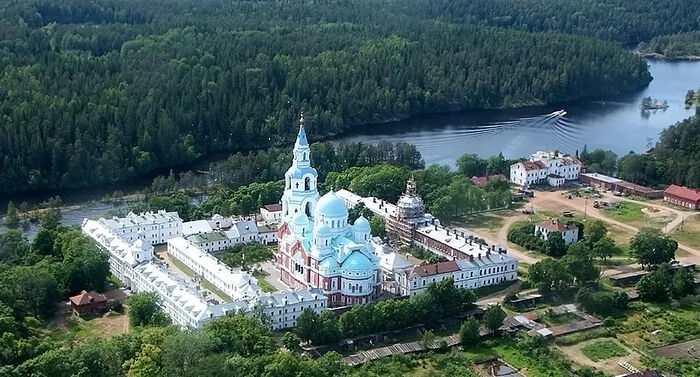

Valaam Monastery

After staying for one more day in Moscow to solve persistent issues of the diocesan life, we embarked for Valaam. I felt obliged to visit the monastery where six years ago, in July 2014, I was consecrated a bishop. While I remember my monastic tonsure well, I have very dim recollections of my ordinations to the deaconate and the priesthood. All that remained in my memory was agitation, apprehension and fear of doing something wrong and annoying Vladyka Alexander (Timofeyev), who performed all three of the most important ceremonies in my life.

For the same reason, I hardly remember any details from my consecration as a bishop. I only recall the extraordinary benevolence of His Holiness Patriarch Kirill who presided over the ceremony and the encouragement and support of the hierarchs who concelebrated with him. The awareness of the fact that I would be in the circles of hierarchs whose faces I had earlier seen only in church calendars filled my soul with a mixed feeling of pride (of course, the sin of pride) and fear (what if I wouldn’t be able to shoulder the burden?).

We spent a few happy days in Valaam. We celebrated the Sunday Vigil and the Sunday Divine Liturgy of the feast of the Prophet Elias at the main Holy Transfiguration Church of the monastery. St. Elias became a “Russian saint” long ago. Religion experts explain Russian people’s love for the Old Testament prophet by the similarity in temperaments of this holy preacher of monotheism and Perun, the Slavic god of thunder. But I don’t agree with them. In my view, the “Russian Elias” has absorbed the traits of a folk character, losing the prototype’s cruelty and adopting the innocent grumbling of a Russian old man. A moving illustration of popular veneration of St. Elias in Russia was the short story, “The Thunderstorm”, by Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977). In it the main character, on a beautiful day after a dazzling thunderstorm, meets the holy prophet, who is struggling to fix the broken wheel of his chariot.

We visited the sketes of Valaam. The first one was All Saints’ Skete, founded in time immemorial on the site of St. Alexander of Svir’s cell; and then, the Gethsemane Skete—the last pre-revolutionary skete of the monastery that was consecrated in 1911. It was the “finishing touch” to another version of this New Jerusalem in the Russian land.

It was in the mid-seventeenth century that Patriarch Nikon was the first in Russia to undertake a large-scale project of the Resurrection Monastery in Istra near Moscow in his attempt to create replicas of ancient monuments of Palestine. As for Valaam, its own “new Holy Land” appeared in honor of Patriarch Nikon himself, one of the most outstanding yet controversial hierarchs in Russian history. The failure of the Church reform and the resulting Russian schism of Old Believers teaches us that Russian spirituality is no less important than the tradition of the early Eastern Patriarchates. The distinctive characteristics of every detail of our worship and the life of our Church are no less precious than the Byzantine rite, which is overloaded with too many elements. A suspicious attitude towards Greeks and the respect for our own tradition helped the Russian people unmask the heresy of Metropolitan Isidore, who was sent from Constantinople to Russia in the mid-fifteenth century. The danger of Greek Phyletism has been clearly revealed again in our days with the OCU.1

The New Jerusalem Monastery on the Istra River and the “Valaam Palestine” weren’t intended to represent exact replicas of the Holy Land shrines. The structure of both monasteries was a mark of respect for sacred history and a dream about the Heavenly Jerusalem, which will appear after the Second Coming, rather than an attempt to replicate the holy sites of Jerusalem.

The Divine Liturgy is indeed “Heaven on earth”. The celebration of the Sacrament of Eucharist is a most elaborate art, in words of Fr. Pavel Florensky—it is the “synthesis of arts”. Symbols play a major role in this synthesis; and as the Eastern rite developed, various allegories were added. Despite their apparent similarity, symbols and allegories have different natures. A symbol is something that unites, while an allegory is something that depicts. In the hierarchical service, the allegorical side is developed to such an extent that it overshadows the symbolic nature of the rite. It is hard to discern the Divine Grace through the veil of opulent ceremony.

Two Divine Liturgies that I celebrated in two churches of Valaam Monastery brought me greater joy than I had expected. Not only did I celebrate without a subdeacon and concelebrating priests—there wasn’t eve deacon, and the “choir” consisted of only one monk. I read the Gospel and elevated the Holy Gifts myself. And one could clearly perceive the unadulterated power of grace underlying the extreme asceticism of the service, which was rather paradoxically combined with the ease of the prayer of intercession before the Holy Altar.

Truly the services were celebrated in a sacred silence, though everything was read and sung properly. The sacrament of the Eucharist was filled with the metaphysical stillness—the very “Heaven on earth” that is the essence of the Eucharist.

The apophatic language of the Holy Fathers is difficult to comprehend, especially for us children of this vain world. The language of art is easier—its rich imagery is a feature it shares with Divine services. The writer Nikolai Gogol (1809—1852) in his book, Reflections on the Divine Liturgy, tried to explain to his contemporaries (many of whom had forgotten the Church) the Eucharist as the essential part of the Liturgy. But the following small poem by Osip Mandelstam (1891—1938) conveys the meaning of the main Orthodox sacrament more accurately:

Lo, the ciborium, like the sun’s golden sphere,

Is soaring on the air, resplendent, ample.

Only the Grecian tongue is fit for sounding here.

The world between two palms: an ordinary apple.

The Liturgy’s zenith moment lets July

Sunbeams under the tall rotunda’s dome,

So we may sigh freely, outside of time,

Of that far meadow from whence time is gone.

On goes the Eucharist like an eternal noon,

All folk partaking, playing, singing, glowing.

In their plain sight, the vessel of Communion,

That fount of joy, towers, is overflowing2.

Those lines came back to my memory after the services. I thought, “How easy it was to celebrate alone as an ordinary hieromonk and how much joy it gave me!” As we used to joke, “I read myself, sing myself and take the censer myself.” I also recalled religious programs on BBC, when through the hellish noise of Soviet jammers we could hear tiny fragments of the Divine Liturgy at the London Dormition Cathedral. Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, who was loved by all the faithful in the USSR, celebrated there absolutely alone as well.

For people who have little to do with the Church, Valaam is associated with the infamous home for the most mutilated, disabled WWIII veterans. Thanks to the journalists, the idea that in the early 1950s, war veterans who had lost their legs or even all their limbs, hearing and eyesight were forcibly sent there, has become a generally accepted opinion. Excluded from society, they had no relatives, often lived on charity, and crowded into barrooms, thus “spoiling” the rosy picture of a “happy everyday life under Socialism.”

There is a grain of truth in this, though. Indeed NKVD (the People’s Comissariat for Internal Affairs) within a short span of time removed such crippled war veterans from streets and sent them to several institutions of this kind in the USSR. Despite the involvement of the law-enforcement agencies in that operation, those who think that these men were forcibly displaced to Valaam are wrong. Maimed veterans indeed were taken from streets, liquor stores, cheap bars and shady flophouses; but in some families they lived happily till the natural end of their lives. The opening of “invalid homes” wasn’t dictated solely by the concern for the “beautiful façade” of Soviet reality. It was just ordinary humaneness in action. Despite its monstrous ideology, the Government would save the lives and extend the lifespan of helpless people who had were almost completely demoralized and were ruining their lives by drinking out of despair. In spite of their cheerless existence, locals can tell many details of the everyday life of those cripples—it nevertheless was life, in which the all-consuming physical and emotional pain left some room for prayer and repentance.

And on Valaam, amid the ineffable beauty and glory of the nature of Russia’s north, it crossed my mind that even in the Soviet era the persecuted and paralyzed Church paradoxically continued to do good. Desecrated churches and monastery cells in many cases housed orphanages, vocational colleges, dormitories and schools, museums at best and granaries at worst. Vandalized and defaced, churches continued to serve people—mostly non-believers—to the end, till their utter destruction, till the moment they were razed to the ground.

I also recalled that some churches had been wiped off the face of the earth, while other houses of God were appropriated for other purposes and survived till the day of their revival. We know that nothing in the world happens without Divine Providence. What if there is some subtle relationship with the feelings and the funds of those who founded them?

Were they built “with the widow’s mite” or with the funds from tightly-stuffed purses of merchants? Were their sponsors driven by repentance, prayer, a sense of duty and love for God; or the vanity of a landlord who just wished to surpass his neighbor in the height of his bell-tower?

And if there is such a relationship, then what fate awaits the churches that have been built in our days?...

It was time to get ready to set sail back. Diocesan life presupposes the presence of its ruling hierarch. It means a series of never-ending meetings, talks, conferences, negotiations, business trips and other kinds of routine work. It was hard for me to leave Valaam. My heart was breaking at the hour of parting with the austere northern nature. But losing the unexpected joy of solitary prayer was the thing my heart was most afraid of. At some point I began to doubt if what I have been doing for the past six years is so important and if the gift of governing (mentioned by the Apostle Paul in 1 Cor. 12:28 as one of the gifts of the Holy Spirit) is so valuable. After all, a bishop has to be engaged in worldly affairs, though they are connected with the Church. Wouldn’t it have been better to choose a monastic way of life in isolation here, on Valaam? Ora et labora (“pray and work” in Latin)—that was the main principle of monastic life formulated by St. Benedict of Nursia, the father of Western monasticism, in the sixth century. He didn’t say that we should pray, work and command! But mostly, I have to give orders.

But there is also the virtue of obedience. It seems true humility is when you perform your duties patiently. And humility is one of the chief monastic vows. So, after praying and receiving the blessing in front of the monastery relics, we began our return voyage. Good-bye Valaam! Human life is full of surprises. Man proposes, and God disposes! Though we were leaving reluctantly, God willing, we may come back again someday…