Unconditional love

Author and priest’s wife Tatiana Vigilyanskaya continues her discussion with psychologist Olga Lysova-Brodina on the upbringing of children. Today’s talk is about the meaning of unconditional love.

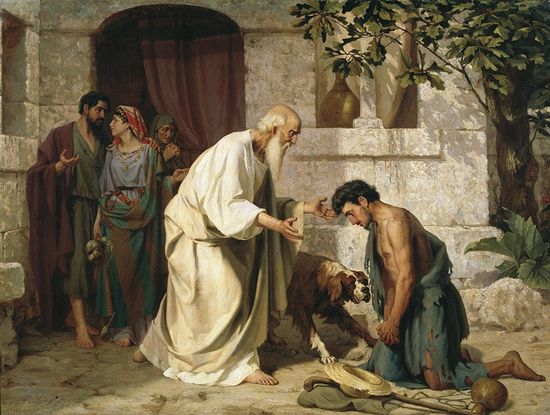

The Parable of the Prodigal Son. By N. Losev. 1882

The Parable of the Prodigal Son. By N. Losev. 1882

—If love for children is an art that we must master on a daily basis, then the science of love should have some foundation, some basis. Modern European psychology and educational science maintain that unconditional love, the unconditional acceptance of a child, exactly as he is, should be this foundation. When it comes to spouses, everything is pretty clear with the unconditional acceptance because we choose life partners whose weaknesses we will be able to tolerate, putting them at the back of our minds. And, most importantly, we are not responsible for the moral make-up of our other halves—it is not our job to raise our spouses. But unconditional love for our children is a completely different thing. And the main difficulty is that no one has cancelled the pedagogical function of parents. We must oppose bad things in our children that can be dangerous to them in the world. And this opposition inevitably leads to conflicts. When a baby is banging its feet, is greedy, mischievous, rolling on the floor of a store; when a teenager is rude, refuses to help his parents with housework, hurts his younger siblings; when the internet leads him off into the unknown, or he is spending time in bad company, we aren’t supposed to smile and accept it as normal! What does accepting a child exactly as he is and opposing evil things in him at the same time mean in practice? Protecting him from evil in the world and staying with him in this world simultaneously?

—Not long ago, one TV channel showed a video clip for parents with rules on how to raise kids. One of the major rules was as follows: One must accept the child exactly as he is with all his merits and flaws. Period! And nothing more. Any thinking person immediately had lots of questions. The main question is: Why should I accept all his faults? Who will help him overcome them? In order to find an answer to these questions, it makes sense to refer to the origins of the “unconditional love” concept and the history of its development in psychology and pedagogy. The concept of love is too big and too profound to be fully comprehended, measured or described by words—which gives rise to numerous misconceptions.

Before looking into the nuances, let’s try to understand what is implied by this beautiful and therapeutic phrase, “unconditional love.”

What is unconditional love? Self Sacrifice and the Theotokos

According to Sergei Ozhegov’s Dictionary of the Russian Language, love is “a feeling of self-sacrificing, heartfelt attachment.” The definition refers to the theme of sacrificial, unconditional love, and Ozhegov gives maternal love as the primary example. This is amazingly accurate. The history of the “unconditional love” concept is directly linked to the miracle of motherhood of the Theotokos. It is thanks to Her purity and meekness that the sacrificial and unconditional Love became incarnate on Earth. And it is the Mother of God that was the first example and source of it (think of the “Life-Giving Spring” icon).

The concept of unconditional love originated in the Christian worldview. It is fully revealed in the Parable of the Prodigal Son because it most strikingly embodies God’s all-forgiving love for mankind, regardless of our love for and obedience to Him! It is sacrificial love, love on the Cross. We see its ultimate incarnation in the love of Christ Who sacrificed His life for every single person irrespectively of how we respond to it—whether we respond, begin to change and strive to enter the realm of everlasting love, or take the path of cultivating and satisfying our passions. It is the Gospel that is our main guide to the realm of unconditional love.

In the ensuing talks, we will return to this theme more than once. But now let’s look how this concept was transformed in philosophy, psychology and education.

Many psychological and spiritual schools of the twentieth century began to consider unconditional love as the supreme form of love. According to them, the main difference between unconditional love and conditional is in the desire to give without requiring anything in return, regardless of the circumstances and the personal traits of the person it is directed at. With time they began to contrast two concepts: unconditional love and conditional love. That led to a controversy about whether conditional love can be considered as love at all. They arrived at the conclusion that maternal love is by nature closer to unconditional love, whereas paternal love is mixed with conditional love because fathers prepare their children for life in the aggressive outside world, which will constantly dictate its conditions. Psychologists have also come to the conclusion that if the parents’ dominant approach is conditional love, their child will be far less happy and less resistant to stress and distress, unlike children who receive unconditional love from at least one parent. If parental love is always conditional, the child will develop a variety of personal and even mental disorders.

Humanistic psychology came into being in the 1960s in America. This school of psychology became the platform on which the Western European concept of unconditional love was developed.

The term “unconditional love” was proposed by a group of psychologists in America, headed by Abraham Maslow (1908—1970), that gathered in the early 1960s to create an alternative to two major psychological theories of the age—Freudism and behaviorism. As opposed to these schools that consider human beings as totally dependent on the environment or subconscious instincts, humanistic psychology considers human beings as responsible for their destiny, making their free choices from the alternatives offered, striving for perfection, existing in the process of formation and change throughout their lives. In Maslow’s anthropological concept, man is one unique, organized whole. This school examines a mentally sane personality who has reached the height of development and self-actualization.

The humanistic approach

Humanist psychology talks a lot about unconditional love, but it proceeds from the humanistic postulate that the human being is good by nature and you simply shouldn’t upset him (this erroneous postulate underlies the ideology of child protection services). But the trouble is that such sane personalities who have attained the height of self-actualization make up only around four percent of the total population. Even so, Maslow held that human nature is good or at least neutral. And that’s a crucial point! It’s here that the fundamental difference in views (of human beings, their nature and the theme of unconditional love) between the spiritually-oriented Orthodox psychology and humanist psychology begins! Adherents of the humanistic school don’t agree that passions and sins are the key destructive powers in the human being. They maintain that all problems stem from frustration (a result of unmet expectations) or lack of satisfaction of primary needs. It is this ideology of dependence on external circumstances that underlies the psychology of consumerism and comfort. If there is comfort, there is happiness and a proper and harmonious development of a personality. If there is no comfort and the basic (instinctive) needs aren’t satisfied, a person degenerates.

The deep, spiritually oriented approach

The Orthodox worldview is fundamentally different from the humanist one because in addition to the good and virtuous aspect, it considers the deep-rooted defectiveness of man, original sin, generic defects, our passions, and personal sins as the main obstacles to unconditional love both for parents and children. According to the Patristic teaching on human nature, the soul is often infected by passions to such a degree that a parent, while understanding (with his mind) the need to show love, warmth and patience and the development of the virtuous part of the child’s soul (using only mild punishment on rare occasions), he can’t put it into practice. He lacks sufficient wisdom and strength, and is in acute need of Divine help.

That’s why in the deep, spiritually oriented approach to parenting we will consider the concept of unconditional love from several perspectives because it has far more components than the Western European humanist school recognizes. These are the Gospel roots, the theme of the God’s image and the likeness in man, freedom, wise strictness, respect for a child’s personality, the theme of the passions and sin that are healed by acquiring grace.

Unconditional love is the highest standard that a parent can strive for, it is the noble aim the Apostle Paul wrote about:

Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up, Doth not behave itself unseemly, seeketh not her own, is not easily provoked, thinketh no evil; Rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth in the truth; Beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things. Charity never faileth: but whether there be prophecies, they shall fail; whether there be tongues, they shall cease (1 Cor. 13:4-8).

The most beautiful example of parental unconditional love is the meek, pure and sacrificial love of the Theotokos. It is in our prayers to Her for our children that we touch the mystery of unconditional love and get an opportunity to initiate it and grow in it. Its center is Christ, and its only sure foundation is a humble mind.

To be continued.