Monk Irinarchos (Mitkas) was born in Greece in 1964. He is a member of the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulcher of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem and abbot of the Monastery of Twelve Apostles in Capernaum (Israel).

—Fr. Irinarchos, you have lived in the Holy Land for thirty years, and for most of this period you have served as abbot of the Monastery of Twelve Apostles in Capernaum, Galilee. Who is it easier for Christians in Israel to live with: Arabs or Jews?

—Last spring on Mt. Tabor I fell from a tree, from a height of thirteen feet. It was the beginning of Great Lent, and we were helping prune the trees at the Transfiguration Convent. While I was falling, my cassock caught on a branch. It reduced the fall speed, but I rolled over and fell on my head. I was in ICU for a week.

Arab doctors saved my life at hospitals, and then my Israeli friends nursed me back to health. Which of them will I complain about?

I returned to the monastery during the lockdown and everything was closed. Nobody could come here. But I suddenly saw some of my Israeli friends kayaking on the lake towards me. That was awesome. An acquaintance of mine who teaches courses for Israeli guides arranged a charity lecture about our monastery via Zoom, raising a decent amount to support us. She did it with the guides who had been out of work for months due to quarantine. Here are my friends: Israeli Jews. Very many helped us.

The fact that I survived the fall is a miracle. I had concussion, a cerebral hemorrhage, several fractured ribs, the displacement of two vertebrae, and clinical death. The doctors said that if I survived, I would be in a wheelchair and insane for the rest of my life.

I remember seeing my body from above and flying in the Heavens. My soul had already departed. But then I came back down just as a feather flies down in the air. You can’t imagine what it feels like!

—Did you want to return?

—I didn’t. It was against my will. Once I returned into my body, it started aching all over.

I spent a week in the ICU in Haifa. At first they didn’t think I would survive. But during the second night I was visited by Patriarch Theophilos, Archbishop Aristarchus and Metropolitan Kyriakos of Nazareth. Their faces were like the images of the Holy Trinity on icons. It was dark all around, with those three faces… After that the desire to struggle for life returned.

Then my memory recovered completely. The doctors were right to decide not to stitch up my head because of the risk of another hemorrhage, since it had been bleeding a lot in the first days. I managed to avoid any operations. Both the doctors and the nurses were wonderful.

My life seemed to have ended with the fall and I was brought to the Light without any alarm. But the Lord prolonged my days. I returned to pain and suffering. But God is here too. How shall I not thank Him?

—There are plenty of monasteries in mainland Greece, its islands and on Mt. Athos! Why do monastics go from Greece to the Holy Land?

—It’s an absolutely different world here. I understand why many members of the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulcher rarely go to Greece. Last time I was there was ten years ago.

Greece is a place where everybody encourages you, kisses your hand and tells you kind words only because you are a monk or a priest. But we don’t have this here—some can call you names or spit at you. This brings you closer to Christ (cf. Jn. 15:20). We shouldn’t expect our situation to be better than His.

In the place where you were born, where people know you and shared the same faith as you since childhood you will be treated kindly. And a place where initially you don’t know the language, customs or anything is a completely different thing. That’s much harder and, therefore, closer to the truth.

I can’t say that I have faced any difficulties in Israel, though. The language is difficult, but I have always been open and sociable.

—Where exactly were you born in Greece?

—Or family comes from a village in northwestern Macedonia. There were both priests and teachers of Greek in our family. I remember my grandma reading prayers while holding the cross that her ancestors had brought from the Holy Land. My maternal grandfather served in the secret services in Asia Minor.

Before the army I studied at a school for electricians where I specialized in elevators as well as an art school, which was engaged in painting churches. I entered seminary after the army when I was twenty-two. I wanted to be a monk from the age of seventeen. I wanted to live in the Holy Land, though I didn’t know why.

—Your whole environment was religious?

—It was. There were 170 students in our school. We vied with each other to help in the altar of our church during services. All of us were believers. Whenever I visit Gorny Convent in Jerusalem, it reminds me of our village by its way of life, cross processions…

Then the village had 1,300 inhabitants. There had been 2,000 before the Civil War of 1946—1949, so in that war we had lost more people than in WWII. We knew what Communism would bring. Greek Communists literally crucified our priests.

In the village I was on friendly terms with our priest. He taught us how to sing, and my first church school was associated with him. On Holy Friday the whole village was at church, we would sing in four choirs. I don’t remember any non-religious people in the village.

My father-confessor organized a small monastery dedicated to St. Parasceva near our village. Every Friday I attended night services there.

Our Metropolitan Augoustinos (Kantiotes; 1907—2010) of Florina taught us many things. He was a wonderful preacher and knew the works of St. John Chrysostom by heart. When he arrived to his metropolis, only two percent of its population went to church, and by the time of his death only two percent didn’t go to church.

Interestingly, Metropolitan Augoustinos and many people around him were anti-monastic in some sense. They were celibate, lived as a brotherhood and were engaged in church activities. Earlier they had belonged to the Zoe Brotherhood. After His Eminence’s death, all the brotherhoods in his diocese became monasteries. I chose monastic life largely thanks to the book by Metropolitan Augoustinos, Follow Me, which astounded me.

—Are Greek bishops monks?

—Not quite. Unlike even young monks in Greek monasteries and on Mt. Athos, they don’t take the great schema. They are tonsured as archimandrites or hieromonks. It depends on the places they live in.

There are some bishops in the great schema, but it is visible during services because they are forbidden to wear their miters. Our bishops often take the schema during their retirement in monasteries.

—There are many small monasteries in Greece. How often do they celebrate the Liturgy?

—If the community consists of five or six monastics, they celebrate the Liturgy on Sundays and the major feasts (they serve Agrypnia at night on the feasts).

Agrypnia is even celebrated in Greek parishes and people attend it. It resembles the way they serve at the Holy Sepulcher: Matins and the Liturgy last till two or three a.m.

In the Greek tradition they serve in monasteries differently from parishes. In Russia the Typicon is monastic.

Historically, in Russia a hermit would retreat to the wilderness, to forests, with cells or a monastery appearing around him. Villages would appear around the monastery, and peasants were its work force. The services remained monastic. Similar things took place in the West. But not in Greece: the laity didn’t do the work for monks in return for their prayers and bread. It was one of the reasons why St. Maximus the Greek was imprisoned—he protested against such relations between the laity and monks. Go to Mt. Athos and look at its monks’ way of life—they labor all day long and pray at night.

—Is it easy for modern Greeks to read St. John Chrysostom in the original?

—Sure. Also St. John Climacus, the Philokalia, St. Gregory Palamas. An ordinary Greek can read the Holy Fathers. Ancient Greek has never disappeared from everyday use. There is much continuity between it and Modern Greek. We still use some ancient words in various expressions.

—Your monastery in Capernaum is a favorite site of Russian pilgrims. You speak excellent Russian, though you have never been to Russia. How did the Russian language and concern for Russian Orthodox people become part of your life?

—My first Russian and Ukrainian contacts were from Mt. Athos. In my youth I twice visited Mt. Athos, including visits to Elder Paisios.

Then I visited the Great Lavra where two elderly monks foretold everything that would happen to me in Jerusalem. They introduced me to two young people—one from Russia and the other one from Ukraine—thanks to them I started learning Russian. Both stayed at our monastery in Capernaum for several years.

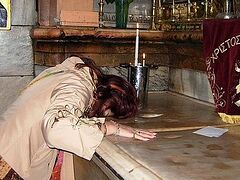

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher

—How did you end up in the Holy Land?

—I wanted to come here as a student with some iconographers who had come here to work. They were my elder brother’s friends. We worked together a little in Greece—they painted frescoes, and I made stained-glass. They invited me to their team (it was three or four times as much as I earned), but I was going to join monastery.

I first came to Jerusalem to spend my senior year at a school. Of the seven young people who had intended to come only three came. Of the three two left. Greeks usually join the Patriarchate of Jerusalem through school.

Students help a lot at the Holy Sepulcher and at the Church of Sts. Constantine and Helen at the Patriarchate. They are paid some money. There is a similar situation with Armenians in Jerusalem. After school, some go and continue their education in Greece, while others are ordained and then pursue their studies.

There are those who came here well-prepared from other Local Churches (as Archimandrite Chrysostomos of Cana of Galilee who is from the Church of Greece). Others came here as young men after the army (as another Archimandrite Chrysostomos from the Monastery of St. Gerasimos of Jordan, or myself). It isn’t dangerous to send those who served in the army to the wilderness or leave them in solitude—they are able to survive. Before settling in the Holy Land you need to live here for a while, and not as a pilgrim; you won’t come to love it until you sweat and work hard here.

As for me, on graduation from school I returned to Greece, served in the army, studied for a while and came back at the age of twenty-four.

—When you returned, you didn’t immediately find yourself in Capernaum?

—It’s not a good idea to stay alone if you have no foundation. You never know how it may end. When I arrived in Jerusalem, I wanted to get to the Monastery of St. Sabbas the Sanctified. But I ended up in the Patriarchate under Archbishop Dorotheos, who now serves at the Tomb of the Theotokos. He is very modest and benevolent. I spent a year in Bethlehem and then at the Holy Sepulcher. After that I was sent to Capernaum.

During my first years on my own in Capernaum, I even lost the monastic aspects I had had in my village, having neither cross processions nor beautiful monastic services. For the first seven years I travelled to Cana of Galilee (where our current Patriarch Theophilos was abbot) every Sunday.

They say in the Patriarchate: “We are monks, but we are unable to live a conventional monastic life. We have different levels, so let everyone live as they can and want. Let him who wants a strong spiritual life go to St. Sabbas the Sanctified; if less—to St. George the Chozebite; if less still—to St. Gerasimos of Jordan. God doesn’t abandon anybody!”

—How was your life in Capernaum regulated?

—Upon arrival here I started to work as best I could. No one could have imagined back then that we would have a Russian Liturgy every Saturday, a parish, 100 Baptisms per year, many weddings—and the number of people keeps increasing!

Since public transportation doesn’t run on Sabbath in Israel, our parishioners help each other get to church. We didn’t organize the choir—people came themselves. I think we were the first in the Patriarchate of Jerusalem to begin to serve for the Russian Orthodox in the mid-1990s. One of our priests died during Holy Week and we were left without a priest for Pascha. A group of pilgrims with a priest came from Moscow. Their priest had served three nights in succession, and our Paschal night was the fourth. When he saw how many people had gathered, he shone throughout the service. The hand of God doesn’t leave His people!

—Are there any restrictions on the construction of churches in Israel?

—No. Churches are built in all Arab Christian villages. A huge new church, like the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in size, has been built in Sakhnin, an Arab village in Galilee. The construction of a church for an Orthodox community is planned in Beersheba. Decisions are taken by mayors and not by the State. If there are at least 100 people of a certain religion in a village or a town, they are allowed to build their house of worship.

—Do you maintain contacts with the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem?

—Of course. Mother Ekaterina, the new abbess of Gorny Convent, has visited us. A doctor by profession, she is very experienced in monastic life and a civil person. Mother Moisea, ex-abbess of the Mount of Olives Convent, often visited us. Her manners were unaffected and not dignified; she would rush to help us pick olives and do other things.

Archimandrite Roman (Krassovsky), the Chief of the Mission, is a true monk and genuinely Russian Orthodox, without a drop of Soviet in him.

I admire Archpriest Victor from Gorny Convent. He is an Armenian from Georgia and speaks Russian with an accent, like me. But when he reads in Slavonic during services, I understand everything. He is a man of prayer. We maintain friendly relations with the Russian parish in Jaffa.

—For all these years you’ve been a monastery abbot and a simple monk (not a priest) at the same time.

—It was my decision. When you are ordained at a very young age, you don’t really understand what it’s like. When our Synod decided to ordain me, I was about thirty. I refused. I just wanted to be a monk in the Holy Land, preferably staying in the same place. Virtually all of our archimandrites are transferred from place to place every three years—you won’t get acquainted with people this way, let alone do something. I didn’t want this.

Shortly before his death, Patriarch Diodoros offered me ordination again and I refused again. Let me be a simple monk here, and priests will be found.