Ekvtime Takaishvili The film, “Ekvtime, a Man of God”, which took two years to make and was dedicated to the life and podvig of St. Ekvtime Takaishvili, was released in 2018. Rezo Chkhikvishvili played the lead role.

Ekvtime Takaishvili The film, “Ekvtime, a Man of God”, which took two years to make and was dedicated to the life and podvig of St. Ekvtime Takaishvili, was released in 2018. Rezo Chkhikvishvili played the lead role.

The first scenes show the village of Likhauri in Guria [a region in western Georgia.—Trans.]—the estate of the noble Takaishvili family. The whole village is searching with torches for little Ekvtime. The child has disappeared without a trace. Then grandma calls one of the men:

“Look, Nino is breathing!”

All those present approach the deceased, covered with a shroud, which is barely noticeably rising and falling rhythmically.

They pull the shroud aside and see the peacefully sleeping boy hugging his dead mother.

These were little Ekvtime’s first impressions of his childhood. He became an orphan early and was raised by his grandmother. The boy’s childhood was overshadowed by an injury: At the age of three he fell from a tree and broke his leg, and remained lame forever.

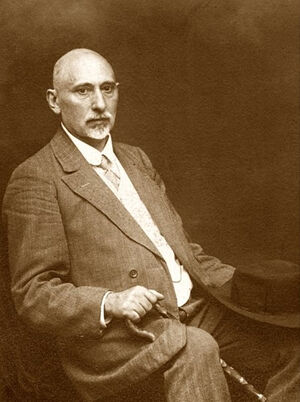

The beginning of the boy’s life was typical of a nobleman of that time. After the Kutaisi gymnasium (classical high school) and St. Petersburg University Ekvtime returned to Georgia and began to teach Latin, Greek and natural sciences at the Tiflis [the official Russian name at the time (1845–1936) for Tbilisi.—Trans.] gymnasium.

He devoted all his free time to travelling around Georgia and collecting ancient manuscripts in monasteries. He understood how important it was to preserve a history not distorted by politics for future generations.

Lameness and a cane, his constant companion, did not prevent him from travelling continually and going to the former lands of Georgia that had become Turkish long before. He collected everything that was of historical value and spent his money on it.

In 1893, at Saguramo, the estate of Prince Ilia Chavchavadze [1837—1907; a prominent Georgian journalist, writer, public figure and a leader of the Georgian national movement of the time.—Trans.], Ekvtime Takaishvili (who was already a well-known historian and archeologist) met Nina (Nino) Poltoratskaya, the daughter of an attorney in Tiflis, and fell in love with her at first sight.

In 1894, on the ruins of Gonio Fortress Ekvtime proposed to Nina and received her consent.

Ekvtime was fortunate to have such a wife. Nina never made scenes when her husband came home on foot after giving his carriage or horses away in exchange for a rare manuscript. And all this in order to collect the great past, bit by bit, and not let it “float away” into the hands of foreign private collectors.

In 1907, Ekvtime founded the Society for Georgian History and Ethnography. He was awarded a gold medal of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg [now St. Petersburg Scientific Center.—Trans.].

Many concerned people, whose main goal was to enlighten their native country (most of the population was still illiterate), gathered around him.

There is nothing of this in the film. The camera jumps selectively to the most critical stages of the hero’s life.

On February 25, 1921, the feast of the Iveron icon, “at the request of working people” some Red Army units entered Georgia. The head of the government of the Georgian Democratic Republic (that existed from 1918 till 1921.—Trans.] entrusted Ekvtime Takaishvili with keeping the treasures of Georgia safe. In one night, he was supposed to collect everything of value, put it into boxes and make an accurate inventory of the national treasures.

These were ancient icons in gold and silver cases, items of gold and silver with precious stones, rare manuscripts, paintings, treasures of the Dadiani Palace in Zugdidi, the property of the Gelati and Martvili Monasteries and many other things. The centuries-old manuscripts were packed into thirty-nine similar boxes with a full inventory.

There is a scene in the film where the cadets are preparing for the last battle on the outskirts of Tbilisi. The general gives each of them a branch from a vine and makes the following speech:

“If we are destined to die here, then grapes will grow in the blood we shed, and future generations will drink in memory of us.”

Soon they would in fact die, since the forces were unequal from the beginning. The Bolshevik regime was established in Georgia.

On March 11, 1921, the Georgian Government departed from Batumi—first to Marseilles, then to Paris, taking all the Georgian national treasures. Noe Zhordania [who had chaired the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia.—Trans.] entrusted Ekvtime to keep them as his most trusted person.

“What an irony of fate!” the academic exclaimed. “I’ve spent so many years trying to prevent the removal of any relics from Georgia abroad, but now I myself have to take out the things I collected with such difficulty.”

He was afraid of a possible attack by bandits and only prayed that he might safely take the treasures to the bank and deposit them. A disabled man with a stick without any guard—and the nation’s treasures!

The ship “Herve Renan” was chosen for that purpose. It was decided to carry the precious cargo on it, but at the last minute a refusal came. After all, it was a warship, and the cargo was secret and “special purpose”. They had to look for another ship—to Istanbul—in a hurry. There they boarded the next ship, “Bien Hoa”, and thus reached Marseilles via Tunisia.

No sooner had Ekvtime and Nina arrived in Paris than they were besieged by an antique-dealer who offered them an enormous sum for the collection. Naturally they gave him a sharp refusal.

In Paris the couple first settled at Avenue Victor-Hugo—at the very hotel where the Georgian delegation was accommodated. Then, in 1922, they relocated to the Leuville Estate they had obtained with the help of the Antadze brothers. After that, Ekvtime completely retired from politics and devoted himself to his favorite business—archeological research and linguistics. Among his many scholarly works, one can single out the Georgian-French Dictionary compiled by him. He filled fifty-five thick notebooks.

Their personal savings had run out long before, and so Ekvtime had his articles printed, read lectures on Georgian culture and history, and published materials of pre-revolutionary archeological expeditions. But all this was too little to lead a decent life. The spouses were in dire straits. Nina, who had been used to a life of luxury in Tiflis, literally had to cook “axe porridge” [an allusion to a famous Russian folk tale of the same name.—Trans.] to support her husband somehow. She also “moonlighted” by giving piano lessons.

If they had sold at least one ring from the treasury, they would have ensured themselves quite a comfortable life for many years, but neither of the spouses ever even thought about that. Instead, each month they scraped together money, penny by penny, to pay to keep the boxes in the bank.

An insurrection against the Soviet rule in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic broke out under the command of Kakutsa Cholokashvili. There were heated debates in the circles of Georgian emigrants about how to help the rebels who needed weapons, horses and medicaments. Some emigrants insisted on selling the national treasures, but Ekvtime was strongly opposed to that.

The new rulers of Georgia drowned the uprising in blood. The remainder of the Cholokashvili detachment and the commander himself managed to reach France.

Ekvtime knew no rest. Now he had to defend the treasures from the encroachments of representatives of the Georgian emigration. In the early 1930s, Takaishvili won a lawsuit filed by Princess Salomea Obolensky (1878—1961; daughter of Nikolos Dadiani, the last Prince of Megrelia), who had tried to sue him for part of the treasury taken from her former family palace at Zugdidi. But at the same time, the court declared the treasures lost due to non-payment for storage and appointed Pierre Jodon their keeper. The treasures were moved from Marseilles to Paris.

In 1931, Nina died of starvation.

It was a huge blow to Ekvtime. Emaciated, he survived only by miracle.

European museums of various countries bombarded Ekvtime with offers to purchase the treasures on favorable terms, offered to store all the others for free in exchange for some of the exhibits, but he would always refuse.

Life in Europe was not quiet and serene. In 1933, the League of Nations recognized the Soviet Union. The treasures passed to the ownership of the French State. In 1934, in addition to his numerous problems, Ekvtime broke his leg again and was bedridden for a long time.

Germany invaded France. With the onset of the war, Ekvtime’s life in a foreign country became even harder. Gestapo men would often come to him to search and turn everything upside down in his home.

Pierre Jodon, at his own peril, sometimes allowed Ekvtime to inspect the treasures, access to which was officially denied to everyone. Ekvtime buried the most valuable things in the ground at night and filled the empty boxes with what came to hand.

Once some Jews turned to him for help, asking him to hide them to gain time while their false passports were prepared and they would be able to flee from Nazis to the USA. Ekvtime replied:

“Every person should help someone else in a situation like this.”

And he gave them refuge in his home.

Pierre Jodon’s driver informed the Nazis that “an old Georgian man” knew the true value of the treasures that were kept in Paris. Ekvtime was arrested and confronted with the informer. At the same time, Priest Grigol Peradze was summoned to the Gestapo.

A German officer said to Fr. Grigol:

“We have information that the treasures of Georgia are stored in one of the Parisian banks. You, as an expert, should assess whether they are of interest to the Reich.”

A thousand thoughts flashed in an instant through the priest’s mind. What exactly was there in the bank vault? Should he agree or not? Would it harm Georgia?

He worried very much. And what he saw exceeded all expectations. With trepidation, Fr. Grigol examined the valuables stored in thirty-nine huge boxes.

“So, what will you say?” the officer who accompanied him inquired.

He was observing the priest’s reaction. The slightest expression of admiration would have given away the true value of the contents of the boxes. But the face of Fr. Grigol who carefully examined the entire collection was impenetrable.

“There is nothing important for the Reich here,” he said. “All this is of interest only to people in Georgia as their historical past for a local museum, nothing more. I can sign the reference letter.”

“All right. I will report it,” the officer immediately lost interest in what was happening.

The unique collection was saved.

And Ekvtime somehow survived until the opening of the Second Front in the summer of 1944. The outcome of the war was clear.

Since Ekvtime had no more strength for the daily struggle, at the end of 1944 he broke down and wrote to Shalva Amiranashvili, Director of the Art Museum of Georgia (1939—1975), with the request to save the national treasures of Georgia, which were threatened with confiscation by the French authorities. They demanded the payment of the debt—for their storage at the Versailles Public Library. Stalin himself, during negotiations with Charles de Gaulle, personally asked him to return the valuables to Georgia. As a result, in April 1945, Ekvtime flew home, accompanying the collection.

Stepping onto the tarmac of the Tbilisi airport, he bowed and kissed the ground which he standing on. It was not just a beautiful gesture—the journey home had been too long.

At first he was very welcome. Soon Ekvtime was appointed professor at Tbilisi University and a little later, a member of the Georgian Academy of Sciences. However, the honor and respect of the Soviet regime was short-lived. Soon he was accused of being an “agent of France” and not only was fired from everywhere, but also deprived of his pension. He was visited by his friends from among academics and by Catholicos-Patriarch Callistratus (Tsintsadze; 1932–1952) only with passes, since house arrest required increased secrecy. They would bring him some food.

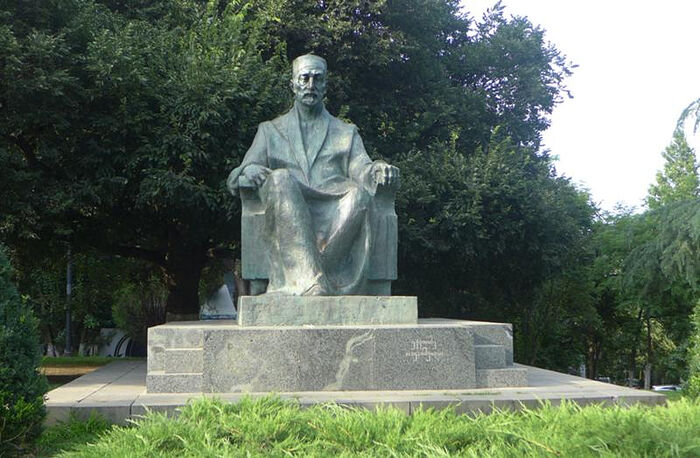

The monument to Ekvtime Takaishvili at the Vere Park in Tbilisi.

The monument to Ekvtime Takaishvili at the Vere Park in Tbilisi.

In February 1953, aged ninety, Ekvtime Takaishvili who lived in dire need passed into eternity. Only a few people attended the funeral of the guardian of the national heritage.

On February 10, 1963, the centenary of his birth, the body of Ekvtime was reburied at the Didube Pantheon cemetery in Tbilisi. When the coffin was opened, it turned out that not only the body, but even his clothes and shoes were intact. Then the relics of the righteous man were transferred again—this time to the Mtatsminda Pantheon necropolis in Tbilisi, where they rest to this day. The body of Nina, his wife, was removed from the Leuville cemetery and buried next to her husband’s relics.

In 2002, the Holy Synod of the Georgian Orthodox Church canonized St. Ekvtime Takaishvili and proclaimed him a “Man of God”. His feast-day is January 3/16.