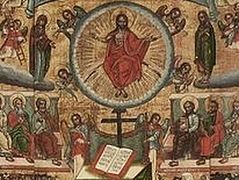

The Last Judgment, from the Oratory of St. Gregory of Nazianzus in Rome. 2nd half of 12th century. Photo: museivaticani.va

The Last Judgment, from the Oratory of St. Gregory of Nazianzus in Rome. 2nd half of 12th century. Photo: museivaticani.va

In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.

Today is the Sunday of the Last Judgment. This Sunday always precedes Great Lent, reminding us that we will be judged. On time I communed an old lady who told me about something that happened to them in the village, when during a funeral, the deceased woman suddenly sat up in her casket. Batiushka ran into the altar scared and the people rushed for the door, nearly crushing each other out of fear. Well, imagine what state they were in, and what state anyone would be in, if a dead person suddenly began to sit up in their coffin. And this woman said:

“Why are you afraid of me? I’m a person just like you.”

They asked her:

“What did you see? What was revealed to you?”

She only replied:

“Judge no one. We will be judged very harshly.”

Judge no one…

Judge not, that ye be not judged (Mt. 7:1), says the Gospel. We must try to fulfill this commandment.

Of course, we break many of the commandments because of the weakness of our nature. Let’s say a man wants to eat, he wants to sleep. He ate—and he broke the fast or ate too much. Or he was too lazy to do something, didn’t pray out of laziness, or slept through something he was supposed to do. Well, what can you do? It’s because of his young age or something.

And what’s condemnation connected with? With what need? Eating, sleeping, or drinking? It’s not connected at all! See how wisely such a commandment is given for our salvation. Judge not—and you won’t be judged. And that’s how it really is. I’ve encountered such cases in my life.

There was a man who would drink out of infirmity: friends, colleagues, circumstances, to feel alive—or again, out of some kind of bodily need. But he didn’t just drink without measure. After all, it’s not said not to drink wine at all, but it says: Be not drunk with wine (Eph. 5:18). And this man also tried to never judge anyone. Before the end of his life, he repented, received Unction and communed, and died like a Christian. Having amended his ways, he left everything behind. Before death, he suffered a serious illness. Who knows, maybe that’s why he tried not to judge: judge not, and you won’t be judged; and the Lord purified him by his sufferings and led him to repentance and confession, so as not to judge him, because he did not judge.

From the holy fathers, we have the example of one monk who didn’t fast as strictly as the others and who had some other transgressions due to infirmity. But when he was dying, the brethren came to bid him farewell, and he was in such a calm, euphoric state. But death was at the door, and he would have to give an account—how terrible! They asked him:

“Why are you so calm? Isn’t there perhaps something you haven’t confessed yet?”

And he said:

“Yes, indeed, I have sinned much out of weakness. But there are two commandments I tried to keep when I came to the monastery: not to condemn anyone and to forgive everyone, holding nothing against anyone. And then angels appeared the day before his repose and said: “Yes, of course, he sinned, but he kept the two commandments of God. It is said: For if ye forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you: But if ye forgive not men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses (Mt. 6:14-15). And again: Judge not, that ye be not judged. If the Lord said it, then it will be so. The Lord will not judge him, but forgives Him everything.”

Do you see what simple conditions the Lord has set for our salvation? In fact, they’re not so hard to fulfill. Let’s say because of our weakness, we can’t fast or pray. Well, but to not condemn—this can be done despite any infirmity.

Of course, it’s not so simple, because even if you yourself don’t condemn anyone, people will try to push you into it. Let’s say they talk about someone, they judge, and you have to assent, as if out of politeness: “Yes, yes, yes...” But if you assent, you have already condemned. We have to especially try to avoid such sins.

The reposed Metropolitan Nikolai of Krutitsa and Kolomna (may he inherit the Kingdom of Heaven) was such a Chrysostom—he had such a gift of speech. He preached beautifully. He spoke such simple words: “Brothers and sisters! Forgiveness for all, condemnation for none—salvation can be easily won.”

To not say this “yes, yes”—you can restrain yourself in this. But after all, non-condemnation isn’t just with the tongue, and forgiveness isn’t just in words, but also in the soul, in the senses, in your heart. It is said: If you forgive transgressions with all your heart… This is, of course, a great podvig, because to forgive from the heart, we have to humble ourselves. And as soon as you try to humble yourself, you begin to understand how hard it is.

The Lord, of course, will forgive if you forgive, and you won’t be judged if you don’t judge. But how difficult it is not to condemn, not to hold a grudge against anyone if you don’t have humility. And humility is in the awareness of our sinfulness—only this makes it possible to be humble. If the thought arises to condemn another, then immediately remember: “Why should I look at another person when I myself am a sinner? And how can I judge another when I will be judged? He’s guilty of one thing, and I’m guilty of another—just as bad or even worse. Perhaps he is sinning out of ignorance, but I sin not out of ignorance. Perhaps that’s his character, his upbringing, his nature, but I have a different nature, and this is what I do…” This is how we must humble ourselves constantly. This is the acquisition of the constant sense of repentance. This is spoken about in the fiftieth psalm: For I know mine iniquity and my sin is ever before me (Ps. 50:5). That means, you must ever keep your sinfulness before you: “I am a sinner—how can I judge another?”

Every sin you see around you should remind you of your own sinfulness. Through this feeling comes humility, by the grace of God, that is, a real consciousness of one’s infirmities. This feeling was characteristic of all the saints.

One of the dearest saints closest to us in time, St. Seraphim of Sarov, always said of himself: “I, the wretched Seraphim.” We call crazy, immature people wretched, but he said it about himself.

The holy forefather Abraham said of himself: I am but dust and ashes. St. Macarius the Great: “O God, cleanse me a sinner, for I have done nothing good in Thy sight.” St. Anthony the Great said: “I’m no monk, of course, but I have seen monks.”

The saints always had such a feeling of humility.

How do we differ from them? First of all, because we do not have this humble feeling all the time. That is, sometimes you will feel you are sinful, and at other times—you’re the judge, and teacher, and guide, and even the accuser: “You’re such-and-such, and why can’t you fix yourself, and what are you doing?!” But you don’t even know what you yourself are capable of doing. This spiritual inconstancy is inherent in us.

One spiritual man, a batiushka close to us in time, told his spiritual daughter: “Sometimes they could write an icon of you, and sometimes a lurid novel.” We all have this kind of behavior.

Forgive us, O Lord!

We have no constancy. We have various impulses, sometimes more frequent, sometimes less. But we must, and this is most important, try to constantly remind ourselves of our sinfulness. This is the main point of the Jesus Prayer: Lord, Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. We need to repeat these words at all times, so as not to forget who we are.

Here’s the simplest example. You’ve come to church to commune. You seemingly prepared—you have to feel that you are a sinner. But often, it’s just the opposite. When you feel like a sinner, then you don’t go to confession and Communion: “I’ve got some kind of coldness in my soul, some irritation, something’s just not right. No, I won’t go.” And you don’t go. But that’s exactly when you should go, because in that moment we sense who we are in reality. But often we only go to confession and Communion when we’ve as if polished and smoothed ourselves out. We seemingly bring our sins to confession, but they’re already combed out, everything’s been let go of, all our sins. And our sin report, so to say, is ready; the balance has already been calculated. But in fact, this inner state is not what is needed for confession and Communion.

And it’s the same after Communion—we inwardly relax, we forget, we no longer remember that we are sinners. Although we’ve communed, we’re still sinners. And that same day, temptations come. And it turns out, that’s our state, our character in general.

Sometimes we say: “I took Communion, and things are sort of bad, somehow.” But, among other things, this doesn’t mean it’s bad. Perhaps it’s the special grace of God so you would feel that although you communed, you’re still far from being a saint, if we can even speak of any kind of holiness in regards to ourselves.

Bishop Ignatius (Brianchaninov) says that all our inner states are states of prelest, that is, false spiritual states.

Sometimes we seem to experience consolation, satisfaction, a certain composure. But at the same time, we avoid the state of repentance that we actually need to have at all times. And if you feel a state of joy and quietness and peace after Communion, that’s good, but you mustn’t forget that you are still a weak, sinful person. That’s the most important thing.

The prayer of St. Macarius the Great gives us an example of such a correct dispensation of the soul:

“O God, cleanse me, a sinner, for I have never done anything good in Thy sight; deliver me from the evil one, and may Thy will be in me, that I may open my unworthy mouth without condemnation, and praise Thy holy Name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.”

“And may Thy will be in me” means he is still asking for it; he doesn’t feel that the will of God is already in him, that is, the self-will is still alive in him. This is in St. Macarius the Great!

He passed through the toll houses in such a repentant state. The demons couldn’t even get near him. They only shouted from afar: “O Macarius, you have escaped us!” And he said to them: “No, not yet.” Then, after he had already gone through the gates of Paradise, the demons shouted: “Ahhh!” It means his soul had passed through and they couldn’t do anything to it. The demons couldn’t reproach him for anything, he was so pure—in an earthly sense, of course. Before God, even Heaven itself isn’t pure. And here, having just entered through the gates of Paradise, St. Macarius said: “By the grace of God, I have escaped you.” That is, still, I am weak, and it was the Lord who had mercy upon me, and therefore I escaped.

This is the state of humility the saints had. How can we, for whom their holiness, purity, and height are incomprehensible, be humbled? What are we compared to them?

Well, perhaps we can’t always remember the saints. But when we see the sins of others (and that’s is the majority of what we see), then we must immediately remind ourselves of our own sins. This is what the saints have always done. When they saw the transgressions of another, they tried to avoid condemnation and remember only their own sinfulness.

There are many examples of this in the lives of the saints. An elder with his disciples was passing by a stadium where competitions were held. There were tournaments earlier too. They’ve had the Olympics since way back when. The disciples said to the elder:

“The devil is amused—sons of darkness.”

But the elder, trying not to condemn them, said:

“Look at how much effort they put into getting a pat on the back or a laurel wreath placed on their heads. We don’t show such zeal for the sake of the Kingdom of Heaven.”

And indeed, look at the drunks—here it’s especially vivid—how they run to the store in the morning. Do we always run to church like that? They burn their bellies with this poison, eating almost nothing—well, maybe a piece of bread or a cucumber—and we say: “Oh, how will I fast? See I have something in my stomach…” But these people don’t think about how to fast. They don’t just fast, but they also poison themselves. Lent is coming. Many people are already thinking: “How will I fast?” Look at the drunks, how they fast, and thereby remind yourself how you should fast for the sake of God.

So the sins we see in others can be didactic for us. If you don’t condemn others, you yourself learn. You can learn, for example, their zeal, which they misuse, but which you don’t have.

Forgive us, O Lord! We have sinned with all our senses, in word, thought, and deed—above all, of course, by pride, conceit, self-justification, selfishness, self-love—how we feel sorry for ourselves, how unhappy we are. We want everything and all kinds of pleasures here. In pride, we sin by self-will, stubbornness, unwillingness to yield to and serve our neighbor, and a lack of mercy.

We have sinned by condemnation, of course, idle talk, denigration, malevolence, malice, slander, profanity, envy, again, because we don’t sense our own sins. If you felt sinful, you wouldn’t be envious, because you would understand: This is what I need, since the Lord sends it to me. “Glory to God for all things!” The Lord sends it to you—thank God.

The apostle James even says: My brethren, count it all joy when ye fall into divers temptations (Jas. 1:2). After all, what is temptation? It, of course, doesn’t just happen, but rather the Lord allows it. Of course, that doesn’t mean that we are doing good when we sin—no. But when we fall into temptation and our sinfulness is revealed, then we see how infirm and sinful we are in general. And we murmur. Forgive us, O Lord!

We sin by discontentment, reproaching one another, malice, ridicule, enticement, gluttony, voluptuousness, indulgence, overeating, vanity, loving praise. Forgive us, O Lord!

We sin by laziness. We are especially lazy in prayer, in doing good works—in general, in correcting our souls.

We sin by accepting wanton, impure, blasphemous thoughts, when all kinds of sinister thoughts come into our minds—this is also our infirmity. Forgive us, O Lord!

We must always remember that a thought that comes is not yet a sin. But if you pause on it, you begin to consider it, you indulge in the dream, then it’s a sin.

We sin with all our senses, mental and physical. Let us pray to the Lord: Lord, have mercy!