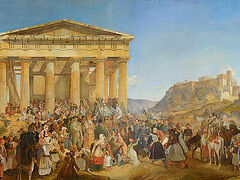

“Two Hundred Years After the Greek Revolution”: We arrive at the topic of Hellenism today, Hellenism in the modern world and specifically, Hellenism outside the modern day nation-state of Greece. What is the state of Hellenism and Orthodoxy amidst the Hellenism of the diaspora?

During the Turkish oppression of 400 years, the Church was the guardian of what might be termed, “the Eastern Roman conscious identity” of the Greeks. Later, after the Revolution of 1821, the state naturally participated in this effort of ethnic cohesion. Greeks were travelers and explorers from the times of the ancients to our own era. The urge to go forth and explore, colonize, and create new worlds is hymned and lauded in Greek literature from the sixteenth-century Erotokritos to the works of Papadiamántis in the nineteenth century to the songs of our own modern Savvópoulos. Exile. Colonization. These are among the defining characteristics of Hellenism’s essence. Until the time of Nasar and the nationalists in Egypt, Alexandria had a thriving Greek community. My own great-great grandfather made a fortune laying marble in Alexandria. One of my distant ancestors, Photius, became Patriarch of Alexandria in the early twentieth century (where, by the way, he opposed the introduction of the new calendar), and until 1955, when perhaps one in four citizens of Constantinople were Greeks.

Segments of the Greeks began to immigrate abroad—at first to far-off America, Australia and Panama (to build the canal)—but also to places like Italian Ethiopia, Eritrea, Uganda and the Congo in Africa at the turn of the twentieth century. During these decades, a Greek family on average had one quarter of its relations abroad. After the Second World War, the Greeks immigrated to Western Europe—mainly Germany, the Cypriots, to the UK—and Canada, and (once again) to the USA, and yet other far-off places. After the economic crisis of the 2000’s, an unexpected wave of immigration, helped by common EU citizenship, made its way to places—some of them quite unexpected—like Hungary, Czechia, and Poland—countries whose citizens themselves had, during the Communist era, immigrated to Greece as a stepping-stone leading to the wealthier European nations. Now roles were reversed, and, once again, Germany and Austria saw an influx of new Greeks.

The direction taken by the Greek ecclesiastical authorities—the guardians of Hellenic identity in the lands abroad among the diaspora—historically, in the new world, sought maintenance of an ethnic ghetto. There is nothing inherently negative about self-preservation... except to say that, historically, Hellenism has sought to “conquer by influence”. Contact with other civilizations is a sought-after affair, and exchange is encouraged. Hellenism seeks to “graft” others to its world by conversion to Orthodoxy and adoption of its habits, its thinking, and its world-view by other civilizations.

Yet preservation of our faith and culture—while influencing the surrounding culture—were never hallmarks of Constantinopolitan policy. The end results of the policy promoted by the Greek ecclesiastical authorities under Constantinople are: decades of food festivals and dance associations, which promoted what may be termed a “distorted” Hellenism. These have nearly ensured the extinction of Hellenism proper in the New World. The focus on Orthodox Christianity was absent; “Americanization” in such a context was the key. How can we look and act more “normal”? How can we rid our church of things like Byzantine music, vigils, and monasticism and cassock-wearing priests, and fill in with European-style choirs with organs, beardless priests in suits, pews, and hymnals? And today, how exactly do we become more “woke” so as not to offend the militant left? How do we promote moral inclusivity and neo-Marxist movements? How do we dilute everything sacred in our worship—even the age-old practices concerning the Holy Mysteries? Admittedly, certain elements of traditionalism—such as the clergy wearing cassocks and beards—made a comeback. These cannot save the irreparable damage done. These are just musicians playing as the Titanic sinks.

Undoubtedly, the fault also lies with our parents and grandparents, many of whom silently allowed this corruption to occur, and others who even affirmed and promoted it for their own gain and for their own purposes (“respected” positions on parish councils, etc.). While I grew up, for example, traditional Greek Christmas carols were ignored; instead, Christmas carols translated into Greek from English (most of which are originally German) were sung. There’s nothing inherently wrong with western Christian carols. But western messages and values permeated my young being, not the messages and eternal truths of our Orthodoxy heralded in the eternal Byzantine carols of the Greeks. The question became: Why this mania of forsaking anything that strikes as Byzantine? Papadiamantis, Seferis, Elitis—these authors—perhaps the most profound Greeks of the past one hundred years—were never mentioned to us as children. No one ever told us of the Erotokritos or Diogenis Akritas.

I had a question as a child that nagged internally at me: each Saturday I was dragged by my blessed mother to Greek School where I was absolutely forbidden to speak English in class. Yet, on Sunday, perhaps half the Liturgy was celebrated in English. Our priest dressed like a Roman Catholic in a suit. Any sense of traditionalism was scoffed at. My young mind did not understand the contradiction, and, without perhaps the proper articulation on an internal or external level, I asked myself a basic question: “Why is our Greek Orthodox Church not really Greek and not really Orthodox?” As more information on Orthodoxy in the traditional Orthodox nations readily became available with the advent of the internet in my early teens, this question only deepened. This question would lead me, at around fifteen years or age, to the respected and ever-memorable Fr. Mikhail Lubochinsky—a man who became a formative father in Christ. He introduced me to authentic Orthodoxy. Later in my life, as I read and translated Papadiamántis many years after Fr. Mikhail’s unexpected repose in 2014, I began to see in this simple Russian priest living in twentieth century Canada an example of a nineteenth-century Greek priest.

What does this mean? Elegant and yet simple, charitable and sacrificial to all his parishioners, faithful in his celebration of the Divine services and the Holy Liturgy, with an unwavering, other-worldly purpose, the ever memorable Fr. Mikhail sought to initiate his spiritual children into the inner mystery which is the true Christian life. Irrespective of their particular background or ethnic identity, all—Poles, Georgians, Greeks and average Canadians alike—were made to feel as equal children under his pastoral care, with no distinctions, no exceptions. Would our ancestors account such a man as not being a Greek? Fr. Georges Florovsky, the eminent theologian (and by coincidence godfather of the aforementioned Fr. Mikhail from whom I was narrated stories of Fr. Georges’ little-known asceticism and fasting) said: “If a theologian starts thinking that ‘the Greek categories’ are archaic, he automatically will lose the rhythm of Catholicity.1 We must be more Greek to be truly Catholic, to be truly Orthodox.” Broadly speaking, the “Greek” referenced by Fr. Georges is defined as the Hellenism born from the early Church Fathers, such as the Cappadocians, who reconciled Ancient Greek philosophy with Christianity. This has nothing to do with genetics and DNA and who is descended from who—these categories are absolutely irrelevant. As a flower, one could say, or as an organism, Hellenism blossomed then, and is growing still.

Would our ancestors account the modern day Greek bishops as true Greeks? The question—“What would the ancestors say?”—is the fundamental question. Recently, Metropolitan Sotirios of Toronto stated: “Let us work together for the glory of God and for our Holy Orthodox Faith in Christ! Only then will we live in peace, unity and love. In doing so, Greeks in Canada will accomplish even greater things! This is what we deserve! This is what we need. Let us all advance as one. Let no one remain behind or forgotten.” And yet, the policy of assimilation within the West promoted by the official Greek Orthodox Church in the past fifty years has failed the Greeks. This policy has ensured that scores—that thousands of Greeks—have become totally Anglicized, and finally, foreigners to the Orthodox Church.

Those who have a conscience know and understand that the official Greek Orthodox Church has absolutely nothing to offer them. It is void of any spirituality, any authenticity, any hint of originality. It has become a parody wherein once a year a food festival occurs, the main goal and focus being the collection of funds—with no absolute existential goal, no ultimate purpose or end beyond the exchange of funds, soulless numbers within a system. We could say it has morphed into a bank with the guise of faith. And reading these words, the Greeks know this message to be true as they see their children apostatizing from Orthodoxy and not speaking Greek, not feeling any particular “tie” to their ancestral homeland—the same homeland Metropolitan Sotirios appeals to to provide Hellenism with “ethical” support. This is not to say anything of the ties the Greeks no longer have with their Byzantine ancestors and the Eastern Roman legacy of Byzantium championed by Fr. Georges Florovsky!

Here is a fact we must all reckon with: The fact that ninety percent of those who identify as Greek Americans are not Orthodox Christians—a fact that the Greek Archdiocese of America ignores. It’s time that we find a new mode of ecclesial existence in order to preserve our faith and identity as Greeks.

Adherence to the Patriarchate of Constantinople in the New World has seen a ninety percent apostasy.2 I ask: why should the Greeks continue to adhere to Constantinople? Since when was adherence to the Greek Archdiocese of America or Constantinople the defining characteristic of Hellenism? Are the Greeks who adhere to the other Patriarchates, such as Alexandria or Jerusalem, any less Greek? Are the Antiocheans, who still term themselves and their Patriarchate, “Greek Orthodox”, though today they are all Arabic-speaking, less Greek? If so, then Kottas Hrístou who died for Greece while screaming “Long live Greece!” in Bulgarian as he was hung by the Ottoman authorities also isn’t Greek. When nineteenth-century Orthodox Slavic immigrants to the new world termed their parishes “Greek Catholic”, what did they reference? The Unia? Obviously not.

They were referencing the Ecumenical Hellenism we mentioned, the distinct combination of Orthodoxy and Hellenism on which our common ancestors, the Eastern Romans, built a mighty empire. Whether we are Greeks or Serbs or Romanians or Russians, this legacy is our legacy. We are all co-inheritors of this legacy. We all share in the common duty of preserving it and influencing modern culture with it. In these uncertain times we live in, in this truly “novel” age of history that has dawned, little stability is left in western society. We must look into the past, to the Faith of our ancestors who intercede on our behalf, and we must seek new historical (though not physical) destinations and solutions to the seemingly insolvable problems we face. Despite the fallen men and women of Byzantium, it was a society wherein Christianity and Christ came first. This is what the common goal should be: that the Kingdom of God is reflected within our own earthly kingdom. Do all men and women not share in this goal as common children of the Father? Is our Eastern Orthodox Christianity not the basis of unity for all?

Here in the West, since the Russian Church has given us the opportunity to live the faith purely, there is no “loss of Hellenism” in doing so from within the Russian Church. After all, what is the difference in being a Greek under the Russian Church or a Greek under the Patriarchate of Jerusalem? How does an Orthodox jurisdiction—a representative of the Eastern Roman Church—“prove” its Hellenism? Were the Greek Bishops who served the Russian Church historically, such as Evgenios Voulgaris and Nikiphoros Theotokis, both of Kerkyra, not Greeks? Here, in the New World, for us Greeks, the preservation of our language, our customs, and our traditions—but primarily our Orthodox Christianity—can only occur under the freedom provided by the Russian Orthodox Church, since the Greek Archdioceses long ago rejected their true vocation. The Greek Archdiocese claimed that Russians can live their faith within it in the so-called “Slavic” Vicariate, composed of defrocked and disgraced Russian clergy who were unfaithful sons. History will prove that I, and those who follow this example, are the faithful children of the Eastern Roman legacy. We invite those who care about the preservation of Orthodoxy and Hellenism—while ensuring their transmittance to the peoples of this land—to come and work with us.