Part 1. Protodeacon Nikolai and Nadezhda Mokhov from New York: Meeting Each Other and Seeing Christ

We continue our interview with the remarkable Nadezhda Mokhova, wife of Protodeacon Nikolai, who serves in the ROCOR Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign in New York City. Nadezhda talks more about Metropolitan Philaret and life in the Cathedral, from the 1960’s to the present.

Metropolitan Philaret in the Mokhov’s garden —How did you perceive Metropolitan Philaret then? What memories of him do you have now?

Metropolitan Philaret in the Mokhov’s garden —How did you perceive Metropolitan Philaret then? What memories of him do you have now?

—Vladyka was an ascetic. But he didn’t frighten us, didn’t forbid us to have fun; rather, he set us up for life by his example. He was the kindest person. Soon after our wedding, my husband suddenly became chronically ill. A special diet was necessary, but money was tight. When Vladyka heard about this, he began to give us shrimp (which were beyond our means) through his cell-attendant, Protodeacon Nikita Chakirov. It was during the fast, and while he didn’t want us to break it, he wanted to support Nikolai. He helped many other people too. When the metropolitan died, Fr. Nikita found a packet of money in his desk—it was to be given to a recently arrived girl to sustain her. Her mother had died of cancer, and the girl was absolutely alone.

Apart from his generosity, he had spiritual charisma. Whenever you entered church while he was serving, there was warmth, a calm and it felt like you were taking off. When I left the service, I would start to go down slowly. It was warm by his side, and it didn’t matter if you talked to him or kept silent.

He could sometimes play a trick on us, but when he spoke seriously, the depth of his state and his words was palpable.

Answering our questions, Vladyka always referred to the Gospel, Patristic works, opening a corresponding place in a book in response to a question. He never spoke from his own authority, like, “I believe that…” He even warned us that if a person said something that contradicted the Church teaching, one should distance oneself from him.

Vladyka was outraged by everything that was overdone. He was against it when women, as if out of humility, “wrapped themselves” in long skirts and girls wore huge headscarves—he believed that modesty is the best ornament for all.

Vladyka was of the opinion that one shouldn’t constantly run after a blessing. A blessing should be taken for Church-related things and not for daily affairs; if you asked for a blessing, then adhere to the instruction. He wanted people to know their faith, understand what goes on in church, understand their prayers rather than repeating them automatically. He gave us one example of misunderstanding the essence: There were nuns who, when receiving guests, put two varieties of jam [“varenye” in Russian] in their plates and poured vegetable oil onto it. When asked why they had done that, the nuns replied, “This is what the Church calendar says: two ‘varenyes’ with oil.”

At times he would ask us questions from the Law of God to see how much we understood the essence of what we believed in.

Vladyka was indifferent to rank. For him all people were equal. He sheltered us all in the club. For me he was a grandfather, a father and a spiritual instructor, all at the same time. That was of great importance in my life. He was a remarkable man with the kind, pure soul of a child; he kept us not around the Church, but in the Church, where we lived and burned, instead of just “being.”

Our club met on Thursdays or Sundays between 1964 and 1985, as long as he was our metropolitan.

In 1984, a year before his repose, he asked us to host a reception on December 14, his name day, and invite everyone who had been to our club. Many people came. Vladyka thanked everyone and said that it was our last meeting for his name day.

We were all so scared to hear this that I flew out of the room in tears. Over time we forgot about it, but a year later, the morning of November 21, 1985, he peacefully reposed in the Lord. It was the feast of the Archangel Michael. Vladyka had been invited to serve at St. Michael’s parish, but he was feeling unwell.

The graduation ceremony at St. Sergius High School, NYC, 1965. Nadezhda is on the far left, Nikolai is on the far right. The night before, the whole of our family went to see him after the Vigil. He lay on his bed, and we came up to him to receive his blessing. When asked about his health, he replied that we would see the next day. At parting he said to me in English, “Do your best.” These words have been my motto ever since.

The graduation ceremony at St. Sergius High School, NYC, 1965. Nadezhda is on the far left, Nikolai is on the far right. The night before, the whole of our family went to see him after the Vigil. He lay on his bed, and we came up to him to receive his blessing. When asked about his health, he replied that we would see the next day. At parting he said to me in English, “Do your best.” These words have been my motto ever since.

We arrived at the cathedral before the Liturgy, and the attendant met us with the words: “It seems Vladyka has died.”

Two years later, Vladyka’s faithful cell-attendant passed away too. Fr. Nikita had first met Metropolitan Philaret in Australia and had been devoted to him ever since.

Fr. Nikita left fifteen pages for me, on which it was written what I needed to do, what debts I was to pay off, what books and vestments I was to sell. There was nothing in his room that was unrelated to the Church and his publishing work, except for a fishing rod!

He entrusted me with continuing publishing two different calendars: that of the Youth Committee, and Martyanov’s tear-off calendar [Nikolai Nikolaevich Martyanov was the publisher of Novoye Russkoye Slovo (“New Russian Word”), the Russian diaspora’s oldest newspaper, and the founder of the historical calendar.—Auth.]. Fr. Nikita had taken care to draw up the youth calendar until 1990 in advance. I reluctantly had to fulfil the will of the dying man. Then I got to like that work and began to publish spiritual books and calendars and spread them throughout the Orthodox world.

These calendars became important to me as a continuation of my education, and knowledge of my roots; at some point I realized that their importance was in the joy they brought to the older generation. We sent them to the homes of people, most of whom due to their age couldn’t go to church, let alone use a computer. They lived by them and kept them.

At the Tolstoy farm

The morning flag-raising ceremony at the Tolstoy Foundation camp. 1955. Valley Cottage, NY —With what other famous people did you communicate in your youth?

The morning flag-raising ceremony at the Tolstoy Foundation camp. 1955. Valley Cottage, NY —With what other famous people did you communicate in your youth?

—In the summer months, I would go to the Tolstoy Farm camp, organized by Leo Tolstoy’s daughter Alexandra Lvovna (1884—1979). I went there from age six to twenty, and Nikolai was a male camp leader there in the 1960s.

Alexandra Lvovna organized the farm and Foundation on land she purchased in 1949 for one dollar from a sister of John Reed, the author of the novel “Ten Days That Shook the World.”

There she set up a large vegetable garden and farm, and invited people who knew how to farm. They would get up early and work all day long, with no complaints. Alexandra Lvovna would join us in the field or the farm. She even taught us how to vaccinate chickens. Grab a chicken by the legs, inject it under the wings and throw the indignant bird into the bushes!

Former ladies-in-waiting of the Empress, people close to the Tsar, former officers, a relative of Doctor Botkin, and such figures as Sikorsky, Malozemov and Solzhenitsin worked with her. The ladies-in-waiting and ordinary working peasants labored and dined together, working on the farm, in the library, or teaching Russian language and history.

There was a big library there. Occasionally, Alexandra Lvovna would read us some writings by her father and weep, because Leo Nikolaevich had been excommunicated by the Church.

There was a church on the farm (it is still there to this day). Alexandra Lvovna would make an agreement with the priest so that when we came to services he wouldn’t drag them out. In the morning, everybody except for the communicants had breakfast. The girls sang with the choir.

With Alexandra Lvovna Tolstaya. 1963

With Alexandra Lvovna Tolstaya. 1963

In the House of the Mother of God

—What was the Synodal Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign like in those years? How has the makeup of the parishioners changed?

—The neighborhood where the premises of the Synod and the Cathedral are located, starting from East 97th Street where it crosses Park Avenue and Fifth Avenue, was inhabited by Russian-speaking emigrants at that time. Long before the Synod moved here, the Holy Fathers’ Church had been opened for Russian-speaking faithful on 153rd Street in Manhattan. Russian restaurants, shops, a Russian school and a bookstore were located along Broadway in the neighborhood. That was when Fr. Anthony (Grabbe) got enthusiastic about the idea of opening a Russian high school there.

Most of the parishioners of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign were emigrants of the first wave who had come to America via Germany and France. There was always a big difference between them and us, who had come via displaced persons’ camps. They considered us “Soviet” and it took them a long time to forgive us for this, but then the difference disappeared with the arrival of the third wave.

Among the cathedral’s parishioners were princes Obolensky, Beloselsky, Golitsyn, Romanov, members of the Cadet Corps and former soldiers of the White Army.

In the late 1970s, a new influx of Russians began. Big, bearded men with huge crosses on the outside of their clothes came and made prostrations. In the 1990s, businessmen in bright clothes showed up throwing around enormous sums of money, but we never saw them again. These were followed by Italian and American converts from Catholicism and Protestantism who had been disappointed with their faiths. They fervently made the sign of the cross.

Nowadays, so many new people are coming that you never know who they are and where they are from.

Pascha. The Cathedral of the Sign. 2019

Pascha. The Cathedral of the Sign. 2019

—Could you say that a parish community has formed in the cathedral?

—There has never been a parish as such here. Parish communities, the way they should be, exist mainly in the churches of Brooklyn, Staten Island, in the suburbs of New York City and in New Jersey. And the Cathedral of the Sign is in fact the house church of the First Hierarch of ROCOR as well as the home of the Kursk Root Icon of the Sign. People come to study or work in New York; they come to the cathedral, attend it, help it—sometimes for five or ten years—and then leave. A similar situation can be seen in the St. Nicholas Patriarchal Cathedral, situated four blocks from here.

The Bagration, Golitsyn, Ledkovsky, and Shatilov families all lived near the cathedral at some point; nearly all of them were our early parishioners. We attended Saturday and Sunday services at the cathedral and more or less formed a parish. Under Metropolitan Anastasius, a brotherhood was set up, and under Metropolitan Vitaly (Ustinov), a sisterhood appeared to support the cathedral materially. We held and still hold festal events at the cathedral. Over time, some parishioners have moved elsewhere, but Fr. Nikolai and I continue to attend the cathedral, which is our home.

I have been at the cathedral since I was twelve; I grew up here, as did my husband. In Europe Nikolai knew St. John of Shanghai. At the cathedral he assisted Metropolitan Anastasius (Gribanovsky), the second First Hierarch of ROCOR.

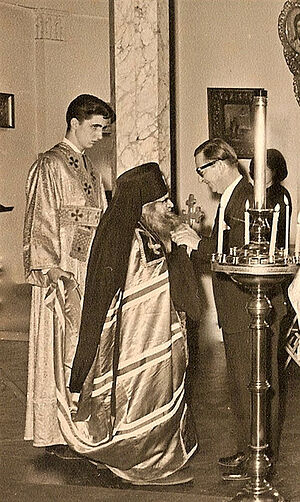

Subdeacon Nikolai Mokhov with Archbishop John of San Francisco in the Synod. The mid-1960s. Far right: Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich Romanov. In 1965, we both graduated from the high school, and in 1969, Fr. Anthony (Grabbe) married us in the Synodal Cathedral. We both were twenty-one years old, and everything in our life has been connected with the Cathedral of the Sign ever since.

Subdeacon Nikolai Mokhov with Archbishop John of San Francisco in the Synod. The mid-1960s. Far right: Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich Romanov. In 1965, we both graduated from the high school, and in 1969, Fr. Anthony (Grabbe) married us in the Synodal Cathedral. We both were twenty-one years old, and everything in our life has been connected with the Cathedral of the Sign ever since.

In 1974, Fr. Nikolai was ordained deacon; I always went to services with him, and, at the request of our warden, Vladimir Kirillovich Golitsyn, I began to sell candles once our sons started assisting in the altar and our daughter was able to sit quietly on her own.

—How did your young family live in those years?

—Six months after our wedding, I graduated from Hunter College with a BA in History and Anthropology. Nikolai became an engineer. As long as our children were small, I took care of them, and on Sundays we went to the cathedral together. I helped in the summer camp and in the Sunday school.

The kids went to services with us on Saturday evenings and Sundays, and when they reached the age of sixteen, we told them that they were now free to choose whether to go to church or not.

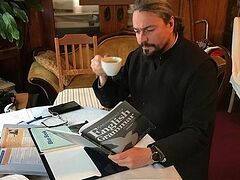

Protodeacon Nikolai Mokhov during a service.

Protodeacon Nikolai Mokhov during a service.

—Nadezhda, have any of your children linked their lives with the Church?

—Our elder son Mikhail works in the civil service and, wherever he moves, he finds an Orthodox church, sings and reads during services. Our middle child Nikolai studied finance, worked in a bank, and in 1994, he moved to work in Moscow. “You taught us to love Russia!” he said to me. And he really loves Russia. During Lent, he visits monasteries and convents near Moscow. His favorite holy place is the Monastery of St. Savva of Storozhev (in Zvenigorod), and on Sundays he travels to the new Church of St. Alexander Nevsky in Istra. Our daughter Lyuba studied to be a journalist, and worked as a manager with musical groups that toured the US; she majored in languages. A deacon’s wife, she now lives in Chicago. All of our children know both Russian and English very well.

Nikolai and I normally spoke in English at home, but when our first child was born we agreed to talk only in Russian. It was not until our daughter was ten or eleven and her friends began visiting her that we started using English at home as well.

—What are some of your most memorable moments associated with the Cathedral of the Sign?

—I’d rather tell you about the memories that make my heart miss a beat. First, the repose of Fr. Gelasius (Mayboroda), to whom I confessed my sins for many years. He was a joyful and peaceful spiritual father and archimandrite. Second, Metropolitan Philaret, who was very close to us, died. That era is gone, never to return.

Third, on the Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy in 2008, Tatiana, the wife of Archpriest George Kallaur, came in worried and informed us that Metropolitan Laurus had just passed away. Although he was the First Hierarch of ROCOR, he preferred to live at Jordanville Monastery. Another era was gone forever.

And, fourth, on the Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy in 2018, a funeral service was performed at the cathedral over our long-term warden and dear friend, Vladimir Kirillovich Golitsyn, with whom we had worked for over forty years. I will never forget those moments.

Pascha, the Nativity and the other great feasts have always been joyful and well-attended at the cathedral. The weddings were wonderful. The Church lived by services, weddings, Baptisms and name days. In our youth, festal meals were organized on our cathedral’s patronal feast of December 10, also on the Nativity, Pascha and the metropolitan’s name day. In the 1960s, the whole meal consisted of tea and cake. We set tables in two halls, the hierarch alone spoke in complete silence, while everybody sat modestly and sedately. Back then no one could have imagined such big meetings and fun as at the numerous buffets and meals we’ve had now (before the pandemic).