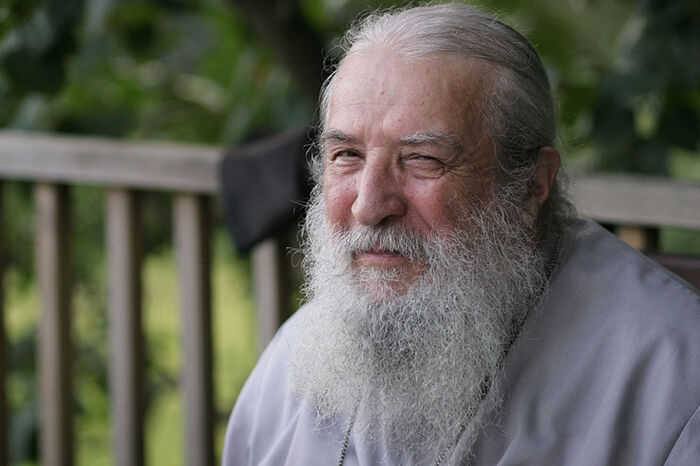

I am very pleased that Archpriest Andrei Sommer, dean of the main church of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia—the Synodal Cathedral of the Sign, agreed to speak with me and answer all my questions, telling me about the pillars of ROCOR, and about his own spiritual path. Here are his stories.—Olga Rozhneva

How I harvested potatoes with Vladyka Laurus

I went to Holy Trinity Seminary in Jordanville. I enrolled in 1988. At that time, Archbishop Laurus (Škurla, 1928-2008), the future Metropolitan and First Hierarch of the Russian Church Abroad, was head of the seminary and monastery. He was also my spiritual father and teacher. I would like to share with you a story that happened thirty years ago, but which is still fresh in my mind.

We seminarians lived at the monastery and had obediences together with the brothers of the monastery—and this was the best spiritual formation for us. The seminarians worked together with the monks in the cowshed, in the kitchen, at the printing press, on the kliros—everywhere. I had my obedience in the bookbinding shop: The monastery printed spiritual books, and I made the covers for them.

We also ate together with the brothers, and our main dish at the trapeza was the most ordinary potatoes, which we grew ourselves. Everyone had the common obedience of working in the potato field when the time came.

One day after trapeza, Vladyka Laurus stood up and made an announcement:

“It’s time—we're all going to the field to gather potatoes today.”

I looked out the window: It had been drizzling for several days already and the field was, of course, wet and muddy, and I desperately didn’t want to go out hunting potatoes in this mud. I was still quite young, having just entered seminary, and I came from dry, sunny California, where young people hadn’t the faintest idea about wet, muddy potato fields.

I’m not saying I was lazy or irresponsible—on the contrary, from childhood I grew up quite a hardworking and diligent boy. I’m just telling you how it was. I myself don’t know what came over me then... I guess we all have our own temptations in our youth, and this is what happened to me.

I had thoughts swirling about in my head: Maybe the rain will stop soon, maybe the sun will peek out. There’re many people in the monastery—no one will notice my absence... Those were the thoughts running through my head as I got into the car and spent an hour driving into the city.

As I drove past the field, I saw this scene: Monks were gathering potatoes into sacks, and Vladyka Laurus himself, who was sixty then, together with all his archimandrites and other brothers was very dexterously digging in the wet ground and nimbly searching for potatoes in the mud, all of their gray beards bending low.

And then my heart was struck with such a strong reproach of conscience that I still remember it although many years have passed. I shot out of the car and made a dash for the potato harvest. I began to quickly gather potatoes, forgetting about the rain and the mud.

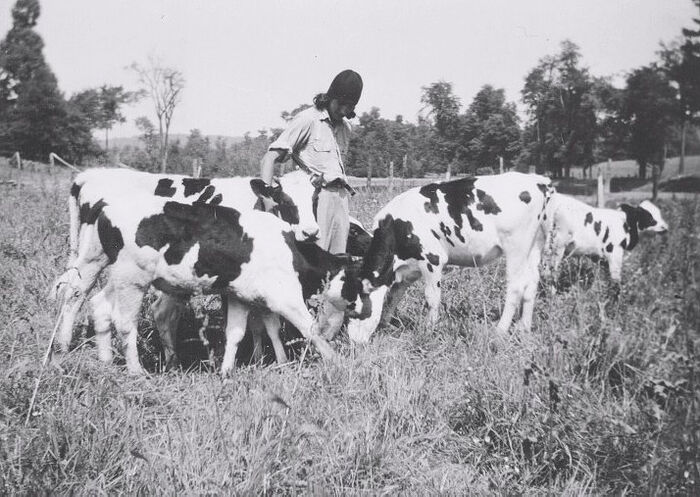

Novice Vasily (the future Metropolitan Laurus) at the pasture in Jordanville

Novice Vasily (the future Metropolitan Laurus) at the pasture in Jordanville

How memories of our spiritual guides help banish proud thoughts

Vladyka Laurus was for us young seminarians an example of humility, meekness, and obedience. He didn’t just teach us this in theory, but in practice, by his own example.

We also saw the humility of the older fathers of the monastery—the hieromonks and archimandrites who weren’t afraid to work for the good of the brethren and the monastery alongside the novices and workers. These fathers were for us young guys an example of Christian podvig in life.

And now, when I, an older archpriest, dean of the main church of the Russian Church Abroad—the Synodal Cathedral of the Sign—suddenly feel a surge of pride for some work well done, I have only to recall to the gray beard of Vladyka Laurus and our spiritual mentors bent low to the wet ground, their modesty and humility, and the proud thought immediately vanishes.

Archbishop Laurus was very busy with the monastery and the diocese and as the secretary of the Synod, and also taught Dogmatic Theology at the seminary. The archimandrites and other elder brethren of the monastery also had quite a lot of work and certainly could have found something more important to do than gathering potatoes. But it was a difficult and dirty general obedience, and they didn’t consider that they had the right to refuse. The higher someone stands on the spiritual plane, the humbler he is. This rule also works in the opposite direction.

I don’t know, however, where there are such monasteries now, where the archbishops would gather potatoes together with the novices...

How Vladyka Laurus broke seminarians of being late to the services

Liturgy was served every day in the monastery at six in the morning, and Vladyka Laurus (if not out on Synodal business), was always at the service. He was also an example of prayer for us. He was strict with himself first of all, and with us—strict, but with love and mercy. This is also one of the spiritual laws: The higher someone stands spiritually, the stricter he is with himself and the more merciful with others. And vice versa.

We young seminarians also got up at five and went to the service, and classes began at eight. If we were late, then Vladyka Laurus would jokingly but firmly take the latecomer by the ear and say imposingly:

“Don’t be late for the service!”

Vladyka had the long and powerful fingers of a musician, and when he grabbed you by the ear, it felt rather sensitive, and after such a reprimand, you no longer wanted to be late to the services. Thus, Vladyka taught us seemingly with a joke, but on the other hand, with strictness.

Vladyka Laurus with seminary teachers and students

Vladyka Laurus with seminary teachers and students

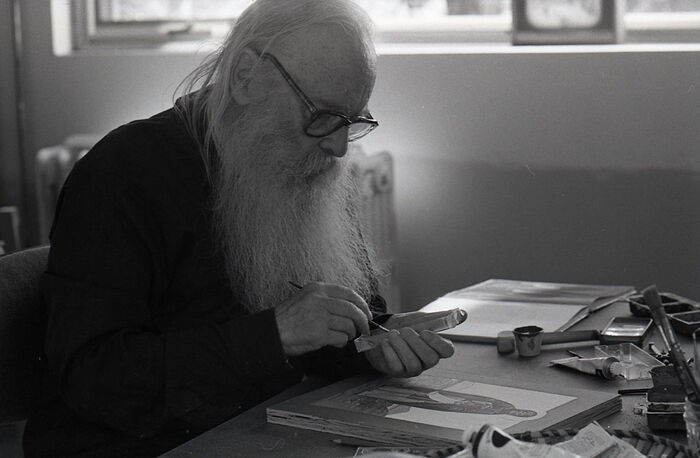

Our Father Cyprian

Another one of our great mentors was Archimandrite Cyprian (Pyzhov, 1904-2001), who is also referred to as the iconographer of the entire diaspora. He lived a long and full life—ninety-seven years—and taught more than one generation of seminarians. He was the spiritual father of many monks and hierarchs.

Fr. Cyprian was born in St. Petersburg. At eight years old he lost his mother, who was a talented artist. He was a teenager when the revolution happened, and when he was fifteen, he joined the Volunteer Army, then left Crimea with the army units and went through Gallipoli. He was well acquainted with want, hunger, hardships, and sorrows. He even worked as a house painter.

He became a novice of the Monastery of St. Job of Pochaev in Transcarpathian Rus’, and it was there that he first painted a church. Among the inhabitants of this monastery were two First Hierarchs of our Church Abroad: Metropolitan Vitaly (Ustinov) and Metropolitan Laurus.

Fr. Cyprian was already eighty when I started seminary. He lived with us, and his workshop was there too. He was always very busy with iconography, but he would find time to keep up with our young lives.

One day I ran out of my cell, not wearing a cassock, in some colorful t-shirt, and I ran into Fr. Cyprian in the hallway. He didn’t just pass by, but said imposingly:

“What, are you wearing some kind of flag?! Dress appropriately!

“The course of the monastic education of the mind, will, and heart”

Much could be said about our mentors at Jordanville. In our education, they followed the instructions of the long-standing rector of the seminary and abbot of the monastery, Archbishop Averky (Taushev, 1906-1976), who was a true pillar of faith and monasticism.

He said:

“Whatever path in life and ministry our graduates choose, we are deeply convinced that they must pass through the course of the monastic education of the mind, will, and heart.”

So we young seminarians went through the course of monastic education, and everything that our instructors instilled in us, we still remember and honor to this day.

My family

By the grace of God, I have been blessed in life to have spiritual guides who have reared me in the faith from a young age. This includes, first of all, my deeply religious relatives. My grandfather was from a long-ago Russified Volga German family and was born in Saratov. In my mother’s family, the men had been priests for 200 years. I even wrote a book about them: The Zatoplyaevs: Our Ancestors Beyond Baikal. My grandmother was the daughter of a priest.

After the revolution, the Bolsheviks persecuted and killed the servants of the Church. In the region where my mother’s family lived, the Bolsheviks killed Archpriest Arkady Prozorov and Archpriest Viktor Kozlovsky. Archpriest Serapion Chernikh, a law teacher at the Khabarovsk Cadet Corps and rector of the cathedral in Nikolaevsk-on-Amur, was seized while blessing pussy willows on Palm Sunday and thrown under the ice in the bay, still in his vestments. Now he and many other such sufferers are glorified as New Martyrs.

Many Russian people, fleeing from a terrible death, wound up dispersed throughout the entire world. This is the Russian Diaspora that the Harbin poet Alexei Achair, a participant in the Siberian Ice Campaign, wrote about:

Fate did not break us, did not bend us,

Though it brought us down to the ground.

And as our Mother Russia cast us out,

We spread Her all around.

My father’s parents left for Harbin—a Russian city in China—where my grandfather worked as an engineer on the Chinese Eastern Railway, and my father, Vladimir Alexandrovich Sommer, was born in Harbin. My mother’s parents ended up in Korea, and that’s where my mother Nadezhda Ivanovna Baranova was born. Then they had many years of wandering about different countries until finally they ended up in California. That’s where my parents met, still quite young at the time, and I was born in Burlingame, a suburb of San Francisco.