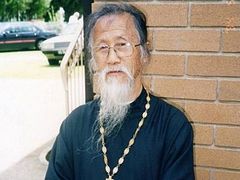

Archpriest Paul Volmensky is one of the most well known Orthodox pastors in Western America; he is rector of the Holy Ascension Church in Sacramento, the capital of California. I am indebted to my dear friend and assistant Mikhail Arsentiev for my meeting and talk with him.

Archpriest Paul Volmensky’s great-grandmother, grandfather and grandmother of were born in the imperial Russia, came to America from China, having made the difficult journey of refugees: Harbin, Shanghai, Hong Kong, England, Rhodesia, Tubabao and San Francisco. During our meeting Fr. Paul recalled their lives, wanderings and amazing adventures.

Archpriest Pavel Volmensky, the Holy Virgin Cathedral—Joy of All Who Sorrow—in San Francisco

Archpriest Pavel Volmensky, the Holy Virgin Cathedral—Joy of All Who Sorrow—in San Francisco

My Grandfather and the Standart Yacht

My roots are in Russia. My great-great-grandfather was from Izhevsk, where he worked as a plant manager, and my great-grandfather, Alexei Nikolaevich Volmensky, was an engineer on the imperial yacht Standart. Our family has had very fond memories of the Royal Family, whose members were very approachable, loved people and could easily and kindly talk even with an ordinary yacht engineer.

His Imperial Majesty with the Crown Prince on board the yacht Standart

His Imperial Majesty with the Crown Prince on board the yacht Standart

The Royal Family with yacht officers

The Royal Family with yacht officers

My great-grandfather fought in the Russo-Japanese War, and after it he remained in Russia’s Far East and owned a ship on the Amur River. He married my great-grandmother, Ekaterina Markelovna—and my grandfather, Viktor Alexeyevich Volmensky, was born in Blagoveshchensk in 1911. The elder son Andrei and two daughters, Nina and Evgenia, Also were born in the Volmensky family.

My great-grandfather Alexei Nikolaevich Volmensky and his children Nina, Evgenia and Viktor (my grandfather)

My great-grandfather Alexei Nikolaevich Volmensky and his children Nina, Evgenia and Viktor (my grandfather)

My grandfather Viktor Alexeyevich, a Russian scout

My grandfather Viktor Alexeyevich, a Russian scout

My grandfather, a trumpet player

My grandfather, a trumpet player

When my grandfather was five years old, my great-grandfather took his family to Harbin and there he owned a ship on the Songhua (Sungari) River, which is a tributary of the Amur.

Harbin was a city of Russian railway workers who came to the region to build the Chinese Eastern Railway (the C.E.R.). At the end of the nineteenth century, Russia and China signed an agreement on the construction of this railroad. Gradually the Chinese Eastern Railway became the largest Russian enterprise in Manchuria, and tens of thousands of Russians came to work there. My grandfather’s elder brother, Andrei, also got a job in the engineering department of the C.E.R.

In addition to railroad workers, Russian merchants, entrepreneurs, peasants and representatives of other classes flocked to Harbin.

Near the bridge over the treacherous and fast Songhua, yellow with particles of loess, there stood the small Chinese village of Khaobin—in its place the beautiful Russian city of Harbin arose. Initially it consisted of tents and hastily assembled barracks, but it grew very quickly.

“Russian speech meets us at the station”

The Harbin poet Gregory Satovsky-Rzhevsky, who died of tuberculosis at the early age of forty-six, wrote poignant lines about the C.E.R. and its stations, one of which was Harbin:

I wander with indifference through foreign cities,

An eternal wanderer without home or contacts,

But in exile the word “Anda” [a district in Suihua, China.—Trans.] will be remembered,

That Russian desert oasis.

The train rushes through the steppe. You won’t find a single bush

In those yellow Manchurian plains.

Suddenly it smells of quiet sorrow once more

On the platform, a familiar sight:

A Russian pointsman with a gray, faded flag,

A waddling Russian with an oil-can,

And a Russian stationmaster came out to the train

With a red cap band and a shining staff.

At the station we are welcomed by Russian speech,

Russian faces smile,

A fair-haired young man with a stick

Drives an obedient bird into the grass.

Just as in a Russian village cows wander around,

Their owners meet them at the gates,

And in every house here the newcomer is invited

To endless Russian tea...

In Harbin, the Russian city on Chinese soil, the old order of the imperial era was preserved for a long time—as though pre-revolutionary Russian life had been “mothballed”.

Even in 1945, when Soviet troops entered Harbin, the new commandant of the city, the Soviet Major General Skvortsov, testified:

“When I got to Harbin, I had the impression that I was in the past. Bearded coachmen in long tight-fitting coats rode along the streets, flocks of laughing schoolgirls ran around, gentlemen slightly raised their bowler hats, greeting each other, and priests in black vestments sedately made the sign of the cross in front of the church domes.”

The small yet savvy Vasenka

There, in Harbin, my grandmother, Evgenia Vasilievna Kirova, was born in 1913. Her father, my great-grandfather, Vasily Ivanovich Kirov, came to Harbin from Bessarabia. He had an interesting life, like all my relatives. The Kirovs had nine sons, eight of whom were tall, broad-shouldered and fit for any kind of work, while the ninth boy, Vasenka [an affectionate form of the name Vasily.—Trans.], was the last-born child. Small in stature and frail, he was not even taken into the army.

The army doctor, however, spotted the savvy boy and began to teach him medicine. Vasya [a diminutive form of the name Vasily.—Trans.] grasped everything easily. His excellent memory, ingenuity, insight and natural intuition of a gifted doctor made up for his weak physique. He became a doctor and after arriving in Harbin was in great demand, curing patients of all kinds of gastrointestinal diseases, which were very common at that time.

Vasily Ivanovich died in Harbin in 1958. His daughter Zhenechka [an affectionate form of the name Evgenia.—Trans.], my grandmother Evgenia Vasilievna, was in Shanghai, Hong Kong, England, America... But we will talk about this later.

Meanwhile it was 1930, and the seventeen-year-old Zhenechka Kirova was one of those giggly schoolgirls graduating from the Russian gymnasium (classical school) in Harbin. Each of those girls took a huge number of subjects in the gymnasium curricula, which included (in addition to physics, chemistry and mathematics) hygiene, cosmography and even the theory of versification that had once been studied by the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum students...

My grandmother Evgenia Vasilievna in her youth

My grandmother Evgenia Vasilievna in her youth

My grandmother Evgeniya Vasilievna

My grandmother Evgeniya Vasilievna

The Volmenskys and the Kirovs in Harbin

My family got on very well in Harbin. One of my great-grandfathers navigated a ship on the Songhua, and the other great-grandfather treated people. My grandfather, young Viktor Volmensky, dreamed of getting a higher education and becoming a geologist, and my grandmother, young Zhenechka Kirova, graduated from high school.

There were many educational institutions, including higher ones, in Harbin; there were theaters, a circus, and a ballet. For railway employees and other residents of the city red brick houses were constructed, mostly one-storied, with two apartment for two families. There were also two-storied houses with two apartments downstairs and two upstairs. And there were mansions of famous people, outstanding in various spheres of life: scientists, teachers, highly qualified engineers of the C.E.R., art workers, wealthy merchants and industrialists.

The Churin and Co. department store in Harbin

The Churin and Co. department store in Harbin

Oleg Gennadievich Goncharenko, a well-known historian and author of many books about imperial Russia, wrote:

“The general desire of Harbin residents was to surround new houses with dense vegetation, converting it over time into gardens, akin to those that had once delighted the eye in their native Orel or Saratov provinces... The interiors of apartments were decorated with ficuses and geraniums—details of everyday environment that had migrated to Harbin from the former Samara, Tula or Penza provinces together with their inhabitants.

“Sheds and kitchens gardens appeared in a couple of days in the courtyards of newly built houses, and refrigerators were set up for storing fish, berries and champagne. Utility houses were built of extra planks, where the thrifty owner, a railway engineer, would keep garden tools or a stack of firewood for the stove so that during the long cold autumn and winter evenings he could luxuriate on his sofa with a volume of fine literature in a well-heated apartment...

“Comfortable working and rest conditions for railroad employees were something unchangeable, and the railway manager, Lieutenant General Dmitry Leonidovich Khorvat, made it a rule to provide each railroad employee with a state-owned apartment. After all, in addition to the traditionally high salary offered to every engineer who expressed the desire to come to Harbin, comfortable and free housing served as an important incentive to keep newly-arrived specialists in Manchuria, with its inclement climate.”

And wild nature reigned around Harbin: the Manchurian taiga stretched from the east, and on the west there were the immense Mongolian steppes. Oleg Gennadievich Goncharenko cited the testimony of Harbinians:

“The region had a rich variety of animals, game and fish. Meat was purchased not in pounds, but in poods[1] or carcasses. Railwaymen’s cellars were full of wild goats, pheasants, geese, ducks and all kinds of pickles and baked food. There was no end of hospitality. Protracted festivities and holidays; birthdays, name days, wedding parties; christenings and funerals were held in abundance...”

Russian Harbin. Near the railway station

Russian Harbin. Near the railway station

“There were amazing Paschal nights in Harbin”

There were about thirty Orthodox churches and chapels, two church hospitals, four orphanages, as well as three monasteries and one convent in Harbin. There was no shortage of clergy—those wishing to become pastors could enter the theological seminary or the department of theology at the university.

While leaving or arriving at their home city, Russian residents of Harbin prayed in front of the specially venerated icon of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, the patron saint of travelers and wanderers, installed at the station. The icon was also venerated by the Chinese, who called it “Nicholas-helper-at-the-station.”

One of Harbin residents recalled the Orthodox festivals in his home city:

“Harbin had amazing Paschal nights. On the night before Pascha Sunday, the huge city would plunge into darkness. And exactly at midnight, when the priests exclaimed, ‘Christ is Risen!’ for the first time in front of the locked doors of the church, crosses were suddenly lit up over all the churches. It was lighting, of course, but there was a sense that the crosses were floating in the air, cutting through the darkness. It was stunning...

“Christmas and Pascha in Harbin are beyond description. There was a huge table in the dining-room of our house, which during celebrations was all laden with various dishes... A delicious vegetarian table was laid in the evening on Christmas Eve—there were all kinds of porridge, mushroom dishes, etc. And the next day they would break the fast with the famous Harbin ham, sausages, young pork and caviar. There were a lot of fruits: bananas, pineapples, oranges, etc. And on Pascha, everyone broke their fast at night...”

The people of Harbin loved the St. Nicholas Cathedral very much. In 1932, on St. Thomas Sunday, a young and beautiful couple was married in this church: Viktor Alexeyevich Volmensky and Evgenia Vasilievna Kirova, my future grandparents. My grandfather was then twenty-one, and my grandmother was nineteen.

St. Nicholas Cathedral in Harbin

St. Nicholas Cathedral in Harbin

My great-grandmother Ekaterina Markelovna and my grandmother Evgenia Vasilievna, the 1930s

My great-grandmother Ekaterina Markelovna and my grandmother Evgenia Vasilievna, the 1930s

The “ice city” of Harbin

There were also difficulties in Harbin. The local climate did not really suit the Volmenskys (who had come from central Russia), not to mention Vasily Ivanovich Kirov, a native of Bessarabia. Short springs and autumns, too hot and humid summers, and long and very chilly winters when the air temperature dropped to -40 C (-40 F). The Chinese still refer to Harbin as the “ice city.”

Such a climate was hardly bearable even to people with excellent health, to say nothing of Vasily Ivanovich and his young daughter Zhenechka, my future grandmother, who both suffered from ill-health...

Arseny Nesmelov (1889–1945), a poet from Harbin, a White Army officer, member of the Great Siberian Ice March,[2] wrote:

Today the wind is from east to west,

And across the frozen Manchurian land

The blizzard begins to scratch

And runs, disappearing into the darkness.

But the harsh climate of Harbin was still not the end of the world. The worst was yet to come. In 1932, the city was occupied by the Japanese and became part of the puppet state of Manchukuo. Now it became dangerous to live there.

Japanese soldiers on a street of the destroyed Chinese city

Japanese soldiers on a street of the destroyed Chinese city

“Help, dear St. Nicholas the Wonderworker!”

My great-grandfather Alexei Nikolaevich Volmensky died and was buried in Harbin, and my great-grandmother Ekaterina Markelovna managed to move to Shanghai with all the children: Andrei, Nina, Evgenia and Viktor—my grandfather. Viktor left with his young wife, Evgenia Vasilievna.

The Volmenskys sold all their property for a song and hurried to the station. There they prayed to St. Nicholas the Wonderworker in front of his icon: “Help, dear St. Nicholas the Wonderworker!” And the train departed for the south of China. It was not easy to get to Shanghai: there were bands of robbers (hunghutz) around.

Thank God and the holy God-pleaser, they arrived safely. Of course, no one was waiting for them there... Young Viktor’s hopes for a higher education and dreams of becoming a geologist were dashed—there were no Russian universities in Shanghai, and there was no money to pay for his studies either. Besides, his beloved young wife was expecting a baby: In 1934, Vitaly, my father, was born in Shanghai.

My young grandfather with my father, little Vitaly

My young grandfather with my father, little Vitaly

My Kirov great-grandparents never saw their grandson: they corresponded with their daughter (my grandmother) for many years, but they could not meet. They passed away in Harbin in the 1950s.

The Volmenskys left Harbin just at the right time. In 1933, the USSR would begin negotiations with Manchukuo on the sale of the C.E.R. Within a couple of years, the deal would be concluded, and everything that the Russians had achieved there under the Tsar would be lost. In 1935, the great exodus of Russians from their beloved Harbin began. Some decided to go to the USSR, others went to seek their fortune in Shanghai, and then left for Australia, America and Paraguay to become part of the great Russian diaspora and endure all the sorrows in exile, away from their native land.

To be continued…