In the 2008 TV project “The Name of Russia,” Russians had the opportunity to vote for the most significant figure in Russian history, whose name will be inextricably linked with the name of Russia, who will be its symbol. In the end, the victor of the people’s vote was the holy Right-Believing Grand Prince Alexander Nevsky. His name became the symbol of Russia. In this difficult battle, St. Alexander beat out Pyotr Stolypin and Joseph Stalin.

The choice of the Russians who voted for Prince Alexander was unexpected for many. Where are we—and where is Prince Alexander Nevsky?! You would think people from centuries long ago would easily lose to our contemporaries—those who are still remembered by our parents, grandparents, or us ourselves. The names of figures from modern times or the recent past are well known, while names from the distant past have become a legend for many, have become overgrown with myths, and, it would seem, have no meaning for our reality.

What is the thirteenth century, the era of Prince Alexander, in comparison with our twenty-first century in the same land? They were our ancestors, but how different we are from them! At that time, religiosity was the norm—and now it’s more like the exception. Many of the vices of our time were alien to Prince Alexander’s contemporaries. In comparison with us, these people were direct, sincere, and simple. The people of that era weren’t wounded by the corrosion of luxury and comfort like us (after all, comfort has long been the god of modern man); they spent their entire life in constant labors, overcoming frequent adversities in the form of crop failures, pestilences, princely feuds, and attacks from external enemies. And that’s how everyone lived, from the simple peasant to the Grand Prince.

So what influenced those who made the personality of Prince Alexander Nevsky the symbol of Russian history? Perhaps the legendariness and moral purity (compared to our times) of his age, when everything was simple and clear and there weren’t such phenomena as abortions, drug addiction and alcoholism, pedophilia, and weapons of mass destruction; when white was called white and black—black; when people weren’t forced to be tolerant and politically correct, but acted according to Gospel principles: Yea, yea, or Nay, nay (Mt. 5:37)? In those times, you didn’t have bearded women singing on stage and sodomites imposing sodomite laws on the rest of the people. In those times, such people weren’t celebrated, but were excommunicated from the Church and subjected to crackdowns.

Or was the Russians’ choice influenced by the noble aura of Prince Alexander Nevsky, which was brilliantly and accurately embodied in Nikolai Cherkasov’s popular 1938 soviet film? At the same time, we mustn’t forget that Prince Alexander was well and convincingly represented in this vote by the future Patriarch Kirill. It seems all of this was of particular importance in the people’s choice.

The Right-Believing Prince Alexander Nevsky was revered by the people already during his lifetime, but his veneration began especially strongly after his righteous repose. “The sun has set on the Russian land!” the Russian Church primate Metropolitan Kirill exclaimed mournfully at the burial of the Right-Believing Prince Alexander Nevsky. These words eloquently characterize the attitude of the Russian people to the holy Prince, and their awareness of his life as a sacrificial podvig for the salvation of the motherland.

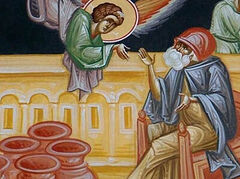

Alexander Yaroslavich was glorified among the saints in 1547, under Metropolitan Makary of Mosow. This canonization implied that the Church sees in Prince Alexander its intercessor, who protected it from the expansion of Catholicism in difficult times, and looks at his life as that of a zealous Christian, filled with spiritual content. By this canonization, the Church shows us that in the life of the holy Prince, there weren’t only crusades and battles, but also fasting, prayerful vigils, and charity to others.

From childhood, Alexander Yaroslavich knew the extraordinary weight of the princely cross. At the age of 16, he was left by his father to rule in Veliky Novgorod, where he had to face the treachery and greed of the Novgorod nobility firsthand. The Novgorod boyars pursued their parochial interests, while the Prince defended nationwide interests. He understood that the boyars’ behavior was weakening the state, contributing to their treason and betrayal of Russian interests, and therefore he fought hard against the attempts of the boyars to infringe upon the princely authority. The Novgorod nobility could hardly tolerate the firm rule of Prince Alexander and therefore, more than once they drove him out of Veliky Novgorod. But at the threat of invasion by foreign invaders, the boyars had to humble themselves and call Prince Alexander to reign again.

Once, Prince Alexander’s father, Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, wanting to keep him with him, sent his other son, Prince Andrei, to help the Novgorodians. But the boyars weren’t satisfied with this. They pleaded with Prince Yaroslav to return Alexander to them. They knew how to ask. Prince Andrei didn’t have the talents of Prince Alexander. Despite his youth, Alexander had already established himself as a capable military commander and farsighted politician. He knew what to do and how to do it.

The boyars remembered how not long before that, Prince Alexander had defeated the Swedish army of Birger Jarl with a small brigade on the Neva River. There was no time at all to gather a large army, and the Prince hoped for a sneak attack. Having prayed in church, he inspired his troops on the field with winged words: “God is not in power, but in truth!” Prince Alexander’s further military victories prove that he was able to assure and lead his troops, to inspire them with confidence in their power. Without any doubt, St. Alexander possessed the true charisma of an outstanding commander. Historians say that he never lost a single battle.

This victory of the Russian army led by Prince Alexander Nevsky over the Swedes prevented the loss of the shores of the Gulf of Finland, the complete economic blockade of Rus’ and interruption of its trade with other countries, and thereby facilitated the further struggle of the Russian people for independence, for the overthrow of the Tatar-Mongol yoke. Our people successfully defended the Neva until the beginning of the seventeenth century. Its temporary seizure by the Swedes ended in their collapse. Defeated by Russia under Peter I, Sweden lost its relevance as a major power. Considering himself a direct successor to the work of St. Alexander Nevsky, Peter I transferred the relics of the holy Prince from Vladimir to St. Petersburg, which he founded.

St. Alexander’s famous victory on Lake Peipus over the German knights, the so-called “Battle on the Ice,” was a decisive blow that shook the Teutonic Order to its very core. This victory provoked the struggle for independence against the knights of the Baltic peoples. The German Order was forced to forget about further encroachments upon the lands of Veliky Novgorod and Pskov. Prince Alexander Yaroslavich took care to protect not only the western, but also the northern borders, establishing the rigorous protection of the Gulf of Finland and the Neva.

But Prince Alexander had to think about the security not only of the western and northern borderlands of the motherland. He saw the main danger for Rus’ in the east. He understood that at the moment, with Russia’s lacking military might, it was impossible to overpower the approaching Tatar yoke. He devoted all his diplomatic talent to pacifying the Golden Horde. He did everything to ensure that the Tatars did not ravage Russian cities and villages and not take the civilian population captive, and he achieved the right to not give Russian soldiers to the Tatar army. To do this, he had to go out to the Golden Horde several times, not knowing whether he’d return alive. That’s how his father, Prince Yaroslav Vsevolodovich, died—he returned from the Horde poisoned.

On the other hand, the Papal curia didn’t abandon its attempts to penetrate into the Russian lands. Having failed to achieve success by military force, it tried to achieve its goals by cunning. Pope Innocent IV of Rome sent two of his cardinals to Prince Alexander, inviting him to familiarize himself with Catholic teachings and accept the Catholic faith. In exchange for this, the Prince was promised military help against the Tatars. The Latins thereby tried to achieve two goals at the same time: to Catholicize Rus’ and to encourage the Russians into a direct armed conflict with the Tatars.

However, Prince Alexander understood that the Pope wanted to push Rus’ to war with the Golden Horde in order to, first of all, facilitate the seizure of Russian lands by the Livonian Order. He refused the proposal of the papal legates, telling them: “We know all of this well, but we won’t accept teachings from you.” And in general, many of the Russian princes of that time had a good understanding of the essence of expansionist Catholicism. Often, they took the Papal agents who were trying to conduct propaganda among the locals and immediately expelled them from the Russian lands without even communicating with them.

In general, being a Grand Prince in the second half of the thirteenth century was simply mortally dangerous. It was a very heavy burden. Prince Alexander bore this cross worthily, strengthened by the power of God. Otherwise, he wouldn’t have been able to endure. What was the price of the intrigues and machinations of the appanage princes, who coveted the Grand Duchy? The Prince understood that as long as Rus’ was divided into principalities, it would never be delivered from the Tatar yoke. Therefore, his main strategic task was to unite the Russian lands around one center. And gradually his plans were implemented. To do so, he had to maneuver between the ambitions of the appanage princes and the demands of the Golden Horde. Being the Prince of Vladimir-Novgorod, Alexander Yaroslavich, conducting a foreign policy corresponding to the interest of the unification of Rus’, managed, relying on the broad layers of serving boyars and nobles, to unite all of northeastern and northwestern Rus’ in his hands.

Yes, there was much he didn’t manage to do, but he left it to his children and grandchildren not to deviate from settling this main task. And his grandson Prince Ivan Kalita, who made Moscow the political center of the country, did much for the unification of the Russian lands, in which every Moscow prince subsequently invested, eventually enlarging Rus’ to a considerable size.

As the famous historian Sergei Soloviev wrote:

“The protection of the Russian land from troubles in the east, the famed podvigs for faith and land in the west, brought Alexander a glorious memory in Rus’ and made him the most prominent historical figure in ancient history from Monomakh to Donskoy.”

Some historians say that Prince Alexander died from being poisoned by the Horde. But the life and activity of the holy Prince took place in constant tension, on the edge of an eruption. He had to overcome so many difficulties and obstacles, solving difficult, fateful tasks on a national scale, that it wouldn’t be surprising if he simply ran out of physical strength.

Prince Alexander Nevsky already became a national hero long ago. The example of his lifetime podvig is the best illustration for modern youth of how to treat their motherland. Don’t flee difficulties to the comfortable West, but overcome all difficulties together with your motherland and protect it to the point of self-sacrifice. As St. Philaret (Drozdov) said:

“Your fate in the Heavenly Fatherland depends on how you relate to the earthly fatherland.”

The Holy Fathers teach that the love of God in a man is seen in how he treats his neighbors. The Right-Believing Prince Alexander Nevsky is holy, because he proved his love for God by laying down his life for the salvation and well-being of many people in Rus’, ignoring his personal interests and comforts.