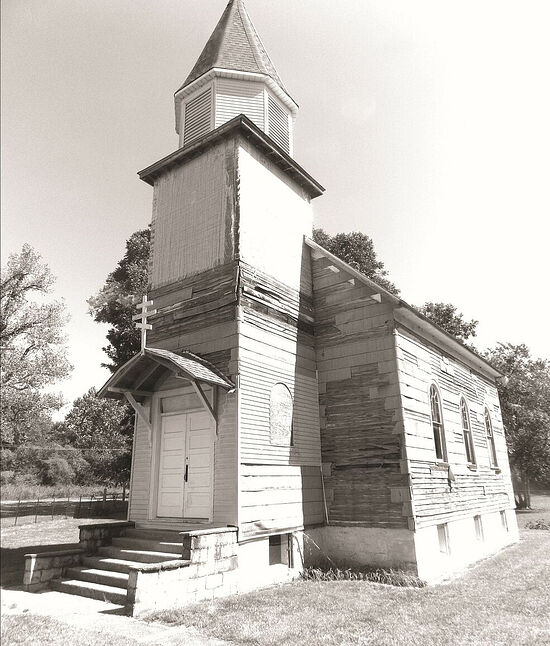

Photo: Brian DeNeal/Springhouse Magazine

Photo: Brian DeNeal/Springhouse Magazine

In 1913, after a migration beginning in 1880 of Carpatho-Russians from what was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Slovakia, Czechia, Poland, Hungary, and Western Ukraine) a church was built in honor of the newly-canonized saint, Holy Hierarch Joasaph of Belgorod—a merciful protector of the poor, in the tiny mining settlement of Muddy, southern Illinois. The town took its name from the Harrisburg-based company operating there—the Big Muddy Coal Company. The immigrant miners were Orthodox Christians when they arrived in the United States, and it was natural for them to build an Orthodox church where they lived, in an area that had scarcely even heard of our faith.

During that nascent period of Orthodox Christianity in North America, the Russian Orthodox Church had the greatest influence and bore the most responsibility for parishes in the new land. Tsar Nicholas II of the Russian Empire responded to the needs of Orthodox immigrants in America by donating funds for the building of churches. He was likewise the benefactor of the Church of St. Joasaph of Belgorod in Muddy, providing funds for its construction and church utensils. Land was partitioned for the church by a Czech immigrant, the miner George Pulaski, and lumber was donated by Barnes Lumber Company. The church was built and consecrated on June 27, 1913, and an icon was presented to it by Bishop Platon of the Russian diocese, with the gramota:

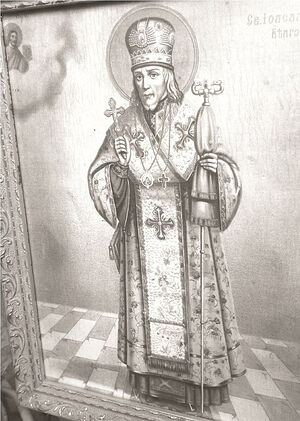

St. Ioasaph of Belgorod. Photo: Brian DeNeal/Springhouse Magazine “His Eminence, the most Reverend Platon, Bishop of the Aleutians and of North America, as a blessing for the new brotherhood of Bishop Iosaf [sic] of Belgorod, and as an unfading memorial: gives to the brotherhood of this servant of God, Ioasaf of Belgorod, in Muddy, Illinois, this icon of Bishop Ioasaf Wonderworker of Belgorod and all Russia, a newly manifest servant of God whose body lay in the earth 150 years and remained incorrupt, and gave many miracles and healing to all who resorted to it with faith, and his incorrupt and honorable body was glorified in 1911, 4/17 September. May the brotherhood flourish by the prayers of Bishop Ioasaf. May Bishop Ioasaf be a faithful and kindly protector. To the brotherhood bearing his name and to his very own brothers according to his ancestors and according to the Holy Orthodox faith which this servant of God held firmly and received salvation and the Kingdom of Heaven. O Holy Bishop, Father Ioasaf, pray God for us.”

St. Ioasaph of Belgorod. Photo: Brian DeNeal/Springhouse Magazine “His Eminence, the most Reverend Platon, Bishop of the Aleutians and of North America, as a blessing for the new brotherhood of Bishop Iosaf [sic] of Belgorod, and as an unfading memorial: gives to the brotherhood of this servant of God, Ioasaf of Belgorod, in Muddy, Illinois, this icon of Bishop Ioasaf Wonderworker of Belgorod and all Russia, a newly manifest servant of God whose body lay in the earth 150 years and remained incorrupt, and gave many miracles and healing to all who resorted to it with faith, and his incorrupt and honorable body was glorified in 1911, 4/17 September. May the brotherhood flourish by the prayers of Bishop Ioasaf. May Bishop Ioasaf be a faithful and kindly protector. To the brotherhood bearing his name and to his very own brothers according to his ancestors and according to the Holy Orthodox faith which this servant of God held firmly and received salvation and the Kingdom of Heaven. O Holy Bishop, Father Ioasaf, pray God for us.”

The community grew and lived the life of honest labor and prayer. Although they had arrived in their new home unlettered, they quickly learned English and even opened an elementary school that was recognized as the best in Illinois. A railway line and power plant contributed to the village’s economic growth, and for a few decades, it was considered a nice place to live. But better conditions in other coal mines, and then the demise of the Illinois coal industry in general, gradually drew Muddy’s Orthodox inhabitants away to other locales. By the 1930s the parish community that once consisted of sixty families was waning in numbers. One family that remained into the 1940s descended from the land donor, George Pulaski. The Russian Orthodox Church, unable to maintain a church with no parishioners, deeded the property to the Kertis family, and Edwin Kertis, Pulaski’s grandson, remained a caretaker of the church and served in the altar as a child. He and sister Madeline Pisani grew up in Muddy but left as adults; however, for many years they never abandoned the St. Ioasaph Church, making regular visits to maintain it and the property around it, even though the church went decades without divine Liturgy. The family even paid over $40,000 in repairs for the building, but an empty wooden structure cannot last forever.

Madeline and George remember well their parents’ and grandparents’ stories of life in the once busy coal mining town. The locals were rather leery of the Orthodox Slavs from so far away, and it took some time to be accepted. That is why Madeline and Edwin have great sympathy for immigrants:

“Our people had a hard life in their native land. They were so poor that they had to send seven-year-old children to Hungary and other places to work in the mines. They considered that it was easier for the little ones to crawl through the narrow passageways. Of course, they lived very modestly here as well, but America gave them the opportunity for a new life.” Edwin adds, “The local folks didn’t understand our people; after all, we didn’t look like them. Local people are always afraid of new waves of impoverished immigrants. Now people are afraid of a new wave of millions of Mexicans. But I think differently. I remember what my ancestors were fleeing from and what they acquired here, and I sympathize with the Mexicans. They’ve also come to work, to have something to feed their families. As time goes by, they will be just like us—ordinary American citizens.”

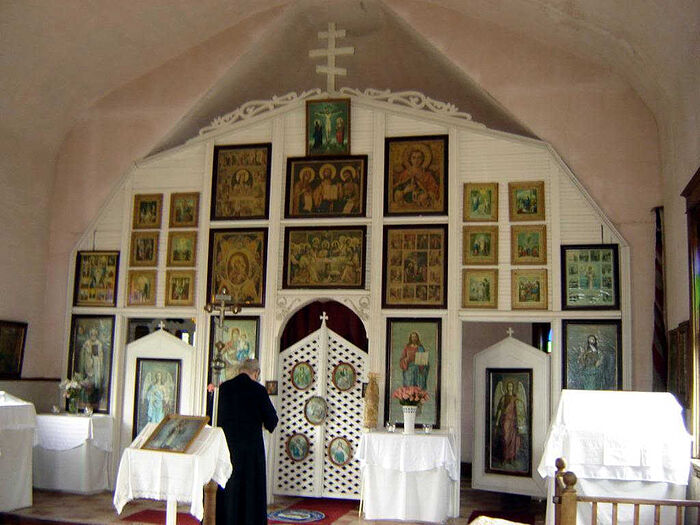

Fr. Martin serving an Akathist at St. Joasaph of Belgorod Church. Photo: StBasilthegreat.org

Fr. Martin serving an Akathist at St. Joasaph of Belgorod Church. Photo: StBasilthegreat.org

Orthodox Christians in the larger vicinity have tried to bring prayer to the abandoned church whenever possible. Fr. Martin and parishioners of the St. Basil the Great Church in St. Louis, Missouri made yearly pilgrimages to Muddy to serve molebens in the church, and pannikhidas in the cemetery. Bishop Peter of the Diocese of Chicago and the Midwest (ROCOR) was concerned for the church, which still needed structural repairs. The roof needed even more work than the Kertises had already financed, the bell tower was on the verge of collapsing, and the financial burden was becoming more than Madeline and Edwin could shoulder. Concerned about the church’s fate, Bishop Peter wanted to investigate the possibility of establishing a monastic community there, so that prayer to the Lord would be renewed and St. Ioasaph would be honored. Finally, on the feast of St. Ioasaph of Belgorod, December 23, 2007, Bishop Peter visited the church to celebrate Divine Liturgy in the church—the first in forty years. The faithful arrived from other Orthodox Churches in the area, and two nuns from other monasteries traveled there to pray and talk about the property.

Bishop Peter at the St. Ioasaph of Belgorod Church. Photo: StBasilthegreat.org

Bishop Peter at the St. Ioasaph of Belgorod Church. Photo: StBasilthegreat.org

The Kertis family had divided the lot some time before and sold a portion to the Illinois electric company, which meant that a huge power station stood just opposite the church. The church itself, as well as the parish house next to it, had no insulation. The reason for this is because in the time of the booming coal business, the locals had plenty of coal for heat, and did not concern themselves with insulation. Edwin noted that he and his family enjoyed fishing in the local pond, but the fish get thrown back—they are inedible. As often happens with “dirty” industry, especially before our times of ecological awareness, the water and land are poisoned. A monastic community never took shape…

Bishop Peter visited the property again in September, 2011 to celebrate the Liturgy on the 100th anniversary of the glorification of St. Ioasaph of Belgorod. It would be the last Liturgy served in that church.

The website of St. Basil the Great Church, St. Louis, Missouri, writes that in 2019, the church was demolished.

"Due to the inability to continue to care for the vacant temple, as well as make the inordinate amount of repairs necessary to insure it, the temple was demolished and properly disposed of in December… As of yet, no plans to rebuild or reconvene have been brought forward to serve any remaining flock in this lower region of Southern Illinois. The Catholicon of the Holy Dormition of the Mother of God—also commissioned by the Tsar-Martyr Nicholas II—remains extant about 150 miles to the northwest of Muddy, and holds occasional divine services."

It is a sad phenomenon—the churches abandoned by transient immigrant mining communities in the U.S. coal belt. How we grieve when an altar guarded by its patron saint and guardian angel is abandoned or destroyed by human hands. It is a reflection of our own spiritual state, of how we so often abandon our own holy of holies, our divine spirit, our faith. Therefore, we can only praise the Kertises for their long dedication to the church of their childhood. We can only hope that a church dedicated to St. Ioasaph of Belgorod, that wonderous yet humble patron of the poor, be once again raised in the United States.1 And we ask his forgiveness for our neglect, for being spiritually incapable of continuing service to and remembrance of him in that once Orthodox locale.