Icons are an essential part of the Orthodox life, and so are found in all Orthodox Churches. Some churches have just a few icons on the icon screen up front, while other churches have every inch of wall space covered with icons, but all Orthodox churches have icons. The identification of icons with Orthodoxy is so complete that the annual commemoration of the restoration of icons to the churches after the period of iconoclasm is not called “the Triumph of Icons”, but “the Triumph of Orthodoxy”.

Visitors to Orthodox churches sometimes wonder aloud why this is. Even when they are too theologically sophisticated to equate icons with idols, we still seem to suffer in their eyes from an embarrassment of riches. They remember how the Second Council of Nicea in 787 compared the kissing of icons to the non-objectionable kissing of the Gospel book and of the Cross (and, the Council might have added, to a Jew kissing the Torah scrolls), and they therefore acknowledge that kissing icons is not idolatrous, since neither the Christian kissing the Gospel book nor the Jew kissing the Torah scrolls worships them when they kiss them. But though icons are therefore legitimate and allowable in churches, they still wonder if this is not too much of a good thing. After all, though icons are allowed, they are not mandatory. There is no rule that says that an Orthodox church has to have lots and lots of icons. So why do we have so many? The answer is two-fold.

First of all, churches have lots of icons of Christ and His saints for the same reason that your grandmother has lots of photos of her children and her grandchildren—because they are beloved family.

There is no law saying that a grandmother has to adorn her wall space with photos her husband in his uniform during the war and photos of their children when they were young and photos of them when they were older and photos of their grandchildren, but I defy you to find me a grandmother who doesn’t do this anyway. These people are her family. She loves them and they love her, and it comforts the human heart to see pictures of people that are loved. (That is also, by the way, why every husband has in his wallet a picture of his wife.) Images are powerful, and they unite us to people we love and care about.

In the same way, the images of Christ and His Mother and His friends (i.e. the saints) are not just historical characters for the Orthodox in the same way that Genghis Khan, Napoleon, or William of Orange are historical characters. They are family, people that love us and whom we love in return. Of course we want to see their faces when we look around us in church.

Family is important. Family anchors us in the world, telling us who we are, how we are to behave, and to whom we belong. And when we are in trouble, it is to family that we turn. In the same way, when Orthodox people need help, they turn not only to God the Source of life (obviously), but also to their spiritual family, asking the Theotokos and the saints for their help and prayers.

Secondly, we also have lots of icons in our churches because worship does not take place on earth, but in heaven, where the saints are. St. Paul told us that though our bodies may be on earth, we are nonetheless sitting with Christ in the heavenlies (Ephesians 2:6), and so that is where the Eucharist actually takes place. That is why at the beginning of the anaphora the celebrant says to the assembled faithful, “Lift up your hearts!” In saying this he is not urging them to cheer up. He is urging them to ascend to where Christ is, and they respond by saying, “We lift them up unto the Lord” (or in one ancient version, “We have them with the Lord”).

The presence of icons around us expresses the truth that our worship takes place with them in heaven. Unlike the west, in Orthodoxy the Church is not divided into “the Church Militant” down here and “the Church Triumphant” up there. There is just one Church, and we all worship together.

This is not just an Orthodox thing. I knew it when I was an Anglican, though I was slow to draw the necessary conclusions from it. The Anglican Eucharistic Prayer of Consecration begins by saying, “Therefore with Angels and Archangels and with all the company of heaven, we laud and magnify thy glorious Name; evermore praising thee and saying, “Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of hosts, Heaven and earth are full of thy glory”. Note: the people praise God with all the company of heaven, because that is where they are—in heaven with them. (Historians will note that Mr. Cranmer, author of the Book of Common Prayer, borrowed this bit from earlier liturgies.)

We note too that this all means that the Church down here cannot be divided by nationalism any more than can the Church in heaven. We are all one people, and our true citizenship comes not from any nation, but from heaven (Philippians 3:20). The saints remind us of this. There are not Ukrainian saints for the Ukrainian people, and Russian saints for the Russian people, and American saints for the American people. There are just saints, and each of them is for all the people. St. Nektarios was a Greek, but he belongs to the whole Church. St. Herman was a Russian, but he too belongs to everyone.

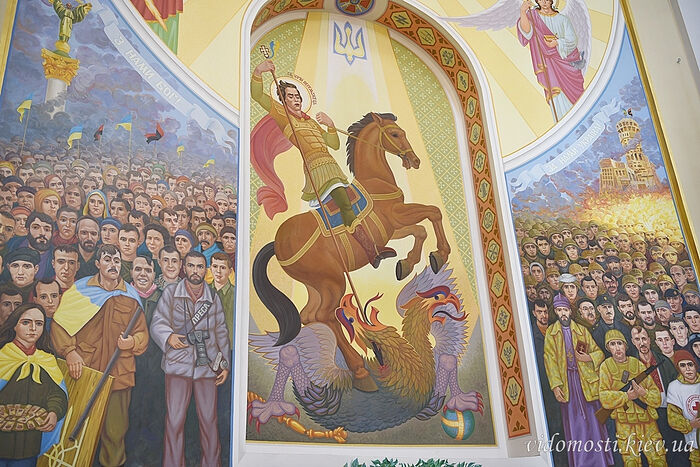

No truly Orthodox iconographer, for example, would show Christ holding an American flag, declaring Him to be “Christ the Saviour of America”, or clothe the Theotokos with the Canadian Maple Leaf, declaring her “the Joy of All Canada”. Christ is the Saviour of all men, not just Americans. The Theotokos is the joy of all who sorrow, not just the joy of Canadians. It is a heretical reduction to coopt Christ, His Mother, and His saints in the service of nationalism or of any earthly ideology.

Mural from Kyiv Patriarchate Church Consecrated 13 October 2018

Mural from Kyiv Patriarchate Church Consecrated 13 October 2018

The wolfsangle in a detail on the mural with Kalashnikov assault rifles below it. Photo: Dimpenews.com.

The wolfsangle in a detail on the mural with Kalashnikov assault rifles below it. Photo: Dimpenews.com.

Nationalism is in principle divisive, and is arguably the cause of most wars. But nationalism (unlike patriotism, which is something altogether different) has no place in the life of the Church or in the heart of a Christian. The presence in our churches of many icons, including icons of saints from different nations, reminds us of this, and silently rebukes us from the walls if we fall prey to nationalism.

Nationalism is very exciting, and it gets the adrenaline flowing, especially in time of war when the media is filled with nationalistic news and lots of flags. That is the time when we should turn to the icons of the saints which adorn our church walls, and reflect that these saints call us to unity and peace. We don’t really need adrenaline, however much the governments find it helpful to their purposes. We need the grace of God. We need the witness and faces of His saints. We need the icons.